Welcome to the second half of our discussion of 16 facts about the Chinese martial arts that you probably don’t know. If you are just joining us for the first time this list is a playful attempt to highlight some popular misconceptions about the Chinese martial arts while subverting a popular genre of (generally information free) internet click-bait. In the top half of our list we covered a number of fascinating facts related to prominent places and personalities who helped to shape the Chinese martial arts.

In today’s post we move on to the top 8 remaining facts. These discussions will focus on the creation of popular concepts surrounding these fighting systems, as well as rethinking the ever popular discussion of “firsts.” Indeed, so many of the historical discussions of the TCMA come down to attempts to determine when something first happened (or who first created it) that it seems only fitting that we should close out our list by challenging some of the conventionally accepted wisdom.

Key Concepts and Images

- Chinese Boxers and their terrible “big swords”…

It is not uncommon for there to be something of a disconnect between the martial arts as they are actually practiced within a certain area, and the popular perception of these communities as transmitted by the international media. For instance, Western discussions of the Japanese martial arts have tended to fixate on unarmed forms of fighting (first judo, and since the 1970s karate), while in actual fact kendo has always been the most popular budo practiced in Japan. And it is not even close. The popularity of kendo just overwhelms everything else. Yet it never managed to capture imaginations in the West to the same degree as karate, judo or even aikido. Hence we tend to have a slightly skewed viewed of what the Japanese martial arts community actually looks like.

Something similar happened in China, but ironically Western popular perceptions moved in the opposite direction. From the final decades of the Qing dynasty onwards, a variety of unarmed combat practices became the most popular martial arts actually practiced by civilians around the country. Of course this era corresponds nicely with the explosion of interest in the modernization of Chinese physical culture during the Republic, and the rise of Taijiquan as a critical marker of traditional Chinese culture.

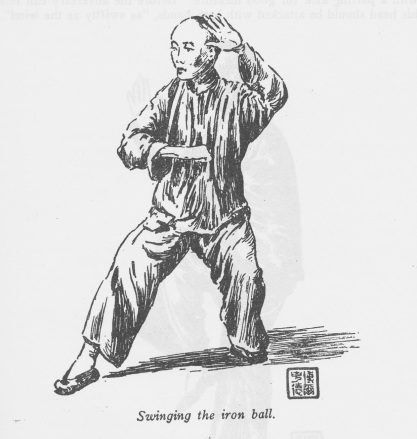

Still, Western produced ephemera, newspaper articles, photographs and even early newsreels emphasized the appearance of alarmingly large swords within the Chinese martial arts. By the 1920s civilian “Sword Dancers” and military “Dadao Troops” had come to dominate the popular Western image of these fighting systems. I suspect that this reflects the lingering cultural impact of the “Boxer Uprising” (one of the largest media events of the early 20thcentury) and the prominence of weapon displays in easily photographed marketplace kung fu exhibitions.

This isn’t to say that there were not a lot of traditional weapons within the Chinese martial arts. Yet just as the prominence of karate in the Western imagination tended to skew our understanding of the actual life experience of many Japanese martial artists, so too did the dadao become synonymous with Chinese martial arts during the pre-WWII period. So, if you are looking for vintage images of Chinese martial artists and you keep coming up empty, try looking for “big swords,” “sword dancers” or “Chinese fencers” instead. You might be surprised with what turns up.

- Kung Fu is a misnomer…

If the dadao came to represent Chinese martial culture in the popular imagination prior to WWII, perhaps no concept became more closely linked with these practices than the name “kung fu” in the post-war era. Of course many are quick to point out that this term actually means “diligent effort” or “hard work”, and that we should really be calling these systems “wushu”. But where did the term kung fu come from, and how did it enter popular usage in the West?

One popular school of thought is that kung fu appeared as a garbled translation or misunderstanding of terms in the 1970s following the popularization of Hong Kong action films. While there is no doubt that it exploded in popularity during that era, its explicit usage as a name for the martial arts in English language publications is decades older than that. “Kung fu” has been a popular shorthand for the martial arts in Cantonese for quite some time. Given the importance of Southern Chinese immigrants in the introduction of these arts to the West, we should not be surprised that their preferred terminology, and other aspects of Southern martial culture, became well established early on.

What is generally not appreciated is that during the late 1910s and early 1920s the Jingwu (Pure Martial) Association began to publish material in English and work with English language newspapers in China to promote the recognition of the martial arts abroad. They decided that if these fighting systems were to succeed they would need a catchy name that could compete with already successful marketplace “brands” like “Japanese judo.” The Jingwu Association started to promote “kung fu” as the proper catch-all term for the Chinese martial arts in English language discussions, and by the early 1920s their efforts had gained some traction. In the modern era the question of how to refer to the Chinese fighting systems has always been somewhat political and fraught. It is a surprisingly complicated subject. But the next time someone tells you that “kung fu” is a misunderstanding that has nothing to do with the martial arts, tell them to take it up with the Jingwu Association.

- “Wushu” has always been the proper name of the Chinese Martial Arts…

This bring us to the term “wushu,” probably the dominant term used to describe the Chinese martial arts today. Typically, when someone objects to the use of the term “kung fu” it is because they advocate the use of wushu instead. [Granted, there are some folks working to bring back “Guoshu,” but that is a subject for another post]. Yet not everyone is comfortable using this term. During the Cold War a number of Taiwanese and Southern Chinese martial artists in North America refused to use wushu simply because it was the preferred nomenclature of the Communist government. Other martial artists (including some in mainland China) didn’t want their folk practices to be confused with the new combat sport (also termed Wushu) being promoted in government backed-schools. Still others disliked the modernist and modernizing “ring” of the term.

What is often not appreciated is that the Communist government, while it did much to promote this term after 1950, was not responsible for its creation or stabilization. Like many words this one has been around for a while, but that doesn’t mean that it was always used in the same way. The Chinese martial arts historian Ma Lian-zhen argued in a 2012 article that this particular honor should go to the warlord, educational reformer and martial arts enthusiast Ma Liang (1875-1947) instead.

Specifically, Ma created a program of simplified martial arts instruction that he sought to make a mandatory part of the physical education curriculum in schools across China. His efforts were supported with the publication of four popular textbooks and a concerted lobbying campaign that generated much debate in the press. And he even enjoyed some initial success promoting his “New Chinese Martial Arts” or “New Wushu.”

While Ma Liang’s political fortunes deteriorated over time, and his training program would eventually be eclipsed by the Jingwu and later Guoshu movements, Ma Lian-shen notes that his efforts were responsible for stabilizing and popularizing the term as an aspect of the modern Chinese language. It even seems possible that one of the reasons why the Jingwu Association explicitly backed “kung fu” was that they were trying to distinguish their program from Ma’s “wushu.” Likewise, the KMT advanced “guoshu” (national arts) as their own preferred term in an attempt to signal the new direction of their program. When the Communist party came to power they wasted no time in dumping the term “guoshu” and turned back to Ma’s “wushu” in an attempt to signal yet another clean break with the athletic policies of the government that had come before. Ma Lian-shen finds that while the current PRC promotes the term wushu, it was actually stabilized and reintroduced into modern usage by a Republic era warlord.

- The western origin of those terrible “How To” books…

Perhaps no genre of publishing is more closely connected to the martial arts than the slim, highly illustrated (and sometimes quite fanciful) “how to book.” Like many kids who grew up during the 1980s, I remember visiting my local library to check out manuals on Tiger and Dragon Kung Fu. That was before I graduated to tomes on Ninjutsu…good times.

It is interesting to note that this seemingly Western genre actually had its origins in early 20thcentury efforts to reform, modernize and save the Chinese martial arts as part of further efforts to reform, modernize and save the Chinese nation. During the early Republic period various liberal intellectuals attacked efforts to rehabilitate the Chinese martial arts precisely because these practices had been associated with the failed Boxer uprising and the illiterate, superstitious, seemingly pre-modern peasants who supported its cause. In an effort to show that the study of martial arts could have cultural value (and therefore a place in an increasingly literate and modern nation) all sorts of martial arts reformers rushed to publish manuals documenting, preserving and promoting their own styles. The savvy marketers of the Jingwu Association were actually kind enough to editorialize on this process, but everyone seemed to feel the same impulse. Increased access to photography and the falling costs of publication and shipping ensured that the 1920s would enjoy a boom in martial arts publications the likes of which China had never before seen.

What were these books like? Well, they tended to be short on detail and the photography was hit and miss. Sometimes they even attempted to teach a basic form, or they might give canned applications. Actually, they were not that different from what I found in my local library as a child in the 1980s.

It is easy to criticize these manuals while forgetting that they are critical primary documents telling us about the rise and global spread of the Chinese martial arts. We tend to forget that the rush towards documentation and publication which created them was once seen as part of a modernizing agenda that aimed for nothing less than national salvation. So whenever you come across a “how to” book of any age be sure to read the front matter and think about how this material spoke to the ideological debates of the day.

The “Firsts”

- The first well known Chinese martial arts master in America was…

As we count down our top 4 facts we also embark on everyone’s favorite subject, the historic “firsts.” Still, as students of martial arts studies it is not enough to simply come up with new and surprising answers when asked these questions at a cocktail party. We also need to think about what each of these facts implies about how we think about the martial arts.

Nevertheless, the answer to our first question must be simple enough. It has become an article of faith that the Chinese martial arts were unknown in America prior to Bruce Lee.

And yet a moment’s thought suggests that this cannot be true. How is it that Boxer Rebellion could be the most sensational media event of the early 20thcentury and no one had heard of the Chinese martial arts until Bruce Lee?

Perhaps what we really mean is that Bruce Lee was the first Chinese martial artist to gain recognition (rather than notoriety) within his newly adopted homeland. Still, while that may be true on the mainland, this seems to ignore a lot of what was going on in Hawaii, one of America’s great cultural mixing pots. But we always seem to ignore Hawaii. For some reason that has become standard operating procedure in historical discussions that always seem to focus on events in New York or California. Certainly, Lee was the first Chinese martial artist to become a media superstar. Yet that seems to set the bar for recognition unrealistically high. How many well-known martial artists can really be said to be “media super stars” today? Perhaps what we should be asking is who was the first Chinese martial arts master to be profiled in a major media source and to be celebrated as such?

If that is how we frame the question, then we need look no further than Wang Ziping. This Muslim martial artist had become a hero of the Guoshu movement during the 1920s and 1930s. And interestingly enough he would go on to play a similar role as beloved “cultural treasure” for a new government after the Communist takeover in 1949. Wang was more than just a strongman and martial arts champion, he had some serious political staying power.

On this side of the pacific he was the first Chinese martial arts master to be profiled and discussed by name in the New York Times. Unfortunately, the circumstances of his appearance were not auspicious. In 1949 Zhang Zhijiang’s once vaunted Central Guoshu Institute was close to collapse. His organization’s manpower and budget had been demolished by WWII, and the KMT, locked in a bloody civil war with Mao’s Communists, showed no interest in restoring his funding to pre-war levels. As part of his campaign to raise the global profile of the Chinese martial arts (and hopefully increase his budget) Zhang went to the NY Times to plead his case. He selected Wang as the figure who was to be held up to the American people as the ideal Chinese martial artist.

Not that it would matter. The last vestiges of the Guoshu program would collapse before the end of the year. Still, Wang would survive. The Communist party would continue to call on Wang’s “star power” when undertaking their own efforts to promote Chinese physical culture as part of their public diplomacy effort. All of this makes Wang the first Chinese martial arts master that a reasonably well read American would have encountered by name in a major media outlet.

- The earliest public martial arts displays…

Prior to the post-WWII era, Western portrayals of Chinese martial artists tended to treat them as a generic class (“boxers” or “sword dancers”) rather than as accomplished individual athletes. And its important to remember that many Wester individuals living in major cities had been given the opportunity to see elements of martial arts performances in Cantonese operas and New Year celebrations (both of which were popular tourist attractions). But when do we encounter the first organized martial arts demonstrations advertised to the Western public as such?

The earliest such displays that I have so far encountered were staged in London in 1851. Billed as an “assault of arms” (again, the term “martial art” would not come into common usage until after WWII), highly elaborate martial arts displays were part of the nightly floorshow that was staged on the Chinese Junk Keying. The first Chinese vessel to make the perilous journey to North America and then Europe, the Keying was a major tourist attraction which attracted the patronage of both royalty and celebrity guests. It even made an appearance in the writings of Charles Dickens. And given the rough and tumble nature of life as a Chinese sailor, it is not surprising that the ship’s crew might have been able to stage a decent martial arts demonstration.

At least that is what I assumed when I first read about the Keying. However, subsequent research suggests that these martial artists were not part of the ships original crew (all of whom had been selected for their ability to serve as part time entertainers). Due to a contract dispute and lawsuit with the ship’s English captain, most of the original Chinese crew of the vessel had returned to their homes in Southern China while the ship was docked in America. As a result, a skeleton crew of British sailors were forced to take the vessel on the last leg of its journey across the Atlantic. That also suggests that the martial artists featured in the 1851 newspaper accounts were hired out of the small Chinese community that already existed in London at the time. The fact that the Keying was able to find the performers necessary to stage their frequent demonstrations offers an intriguing glimpse into the early globalization of kung fu. Who would have guessed that mid-19thcentury London had a Chinese martial arts “community?”

- The first kung fu schools for Western students…

One of the favorite debate subjects that one runs across is which of the Chinese martial arts schools in the US was the first to accept non-Asian students. These discussions are often framed in terms of the courage to overcome secrecy or racial animus. They also have a strange tendency to leave out the fact that it was the Chinese themselves who had been the victims, rather than the perpetrators, of these behaviors. Regardless of which Sifu is said to have opened his doors first, all of these discussions tend to focus on the post-WWII period.

Yet things in mainland China seem to have been a bit different. I suspect that the surprisingly early integrations of Chinese martial arts training into Western run missionary schools and the YMCA/YWCA probably led to all sorts of early cross training that we will never find out about. But we do know from newspaper accounts that in the year 1936 Chu Minyi, who we previously met in the first half of this list, began to sponsor a series of demonstrations for the benefit of foreign citizens who were members of the International Actors Theatre in Shanghai. The response to these initial demonstrations was so positive that a May 31 article in the China Press notes that one Chi Tung Chang had been hired to give regular lessons (presumably on Taijiquan) to interested members. Classes were to be held every Tuesday at 5:00 and members could either receive instruction or watch at no cost as the fee was covered by their club membership.

So much for the “impenetrable secrecy” of the Chinese martial arts. Once again, it seems that the limiting factor in the global spread of these practices was always Western interest rather than Chinese racial animus.

- The first English language book on the Chinese martial arts…

Who wrote the first English language manual of Chinese martial arts? Discussions have tended to focus on figures in the post-WWII era. As such, historical researchers are often surprised when they first encounter numerous translations and discussions of related practices including the “Eight Sections of Brocade” in American magazines and journals dating all the way back to the 1920s. What was the origin of this material and what clues might it provide to the first English language Chinese martial arts manuals?

Western missionary schools in China during the late Qing worked hard to introduce the latest educational methods, and this included an emphasis on athletics and physical development as a means of character development that grew out of the turn of the century theory of “muscular Christianity.” Chinese students who graduated from these schools occasionally worked to promote the spread of athletics within Chinese society, and some even went on to become athletic directors at Chinese college and universities. These individuals would often travel to America or Europe to pursue the graduate training necessary to further their career.

This then led to a ready avenue for informational exchange. Western physical education professors were curious about popular Chinese practices (indeed, the martial arts were frequently discussed in English language papers published in China), where as Chinese students were eager to learn about the latest innovations in coaching and physical training. The end result was the creation of a small but interesting body of dissertations and thesis that showed how these various interests fused in American Universities during the 1920s.

As I discussed in this paper, presented at a 2017 conference in Korea, the most interesting of these works that I have yet encountered was a thesis written by Ma Yuehan. It commented on the growing enthusiasm for martial arts training within university based Chinese physical culture circles. More importantly for our purposes, it also provided English language readers with an introduction to Xingyiquan which covered both the arts history (as it was understood at the time) as well as its practice and application. All of this was augmented with a number of very clear photographs and suggestions for how the exercises in the book could be employed in a Western educational setting.

Unfortunately, like most academic monographs, Ma Yuehan’s 1923 thesis was never published. Instead it sat relatively undisturbed in the archives of the YMCA training college in Springfield MA. Nor is Ma even remembered as martial arts pioneer. In truth he came to Xingyi rather late in life and is better known as a track and field coach and physical educational pioneer in the Western model. Still, his 1923 thesis is a remarkable achievement. If nothing else it reminds us that the fundamental impulses behind the current iteration of martial arts studies are not new. In fact, the very earliest English language martial arts manual that I have located was written by a Chinese scholar seeking to place this knowledge within a comparative and cross-cultural context. That effort dates all the way back to the early Republic period.

Each of these point on our list suggest that history is a funny thing. It is true that Chinese martial arts are not as ancient or timeless as many of their students assume. These practices (as we know them now) arose in the modern era and reflect the concerns of a world that is very similar to our own. Yet much of what we assume first arose in the West during the 1970s or 1980s actually had its roots in China during the 1920s-1930s. This era tends to be neglected in popular discussions of the TCMA as we seek for ever more ancient origins. Still, one cannot understand appreciate the dynamism and resilience of these practices without more closely examining this turbulent and creative period in Chinese history.

oOo

If you enjoyed this list you might also want to see: Two Encounters with Bruce Lee: Finding Reality in the Life of the Little Dragon

oOo

August 9, 2018 at 11:37 pm

Most enjoyable!

August 10, 2018 at 3:25 pm

Chad Eisner, a reader of the blog, sent me a most interesting comment that I thought I would share here as it nicely illustrated the complexity of terms like wushu and kung fu:

“Hey Ben, reading your latest post. A thought occurred to me re: WuShu. From my understanding Wushu is a fairly recent term as well. The Ming texts favor “WuYi” as does the Ma Family. I don’t think I have seen “WuShu” in any of the Ming Texts I have looked at. Gabriel [Chin], [1920-2005] never used the term “Wushu” but “DaQuan” or “WuGong”. Most of my teachers used the term GongFu and reserved WuShu for the modern sport….

Sifu Ma [Yue] said it is a republican era word and that the referred term historically is “WuYi”.”

August 10, 2018 at 4:13 pm

The word used has political implications right up to the present day. The CCKSF (Canadian Chinese Kuo Shu Federation) was distinguished by its connections to Taipei instead of Beijing.

Similarly, there are respected masters in Canada who still use the Wade-Giles “Tai Chi Chuan” rather than the Beijing-approved Pinyin “Taijiquan”.