Introduction

This paper was recently read at the International Conference for the 1st World Youth Mastership held at Cheongju University on Nov. 3-4, 2017. Many thanks go to Prof. Gwang Ok for making this event possible and extending an invitation for me to attend. A special note of thanks also goes to the Cornell University East Asia Program for helping to support this research. My report on this conference is coming soon, but I first wanted to share some of the things that I have been working on for the last six weeks with the readers of Kung Fu Tea. Enjoy.

Civil Society, Mimetic Desire and China’s Republican era “Kung Fu Diplomacy”

Today I would like to talk about an overlooked period in the globalization of the Chinese martial arts. Specifically, who was promoting these fighting systems in the West during the 1920s, and why? Best of all, if we are lucky we may even rediscover the existence of a groundbreaking martial art manual, long since forgotten by the hand combat community, as we answer that question.

This paper is part of a single chapter from a larger manuscript examining the ways in which both state and private actors have employed the martial arts as a source of “soft power” to manipulate China’s image on the global stage over the last century. Such activities are in no way confined to China and are, in fact, a common diplomatic strategy.

In the field of political science this policy is referred to as “public diplomacy.” The topic has generated a rich literature, though many basic questions as to when and how these mechanisms work most effectively remain fundamentally contested. Most of this literature has focused on either Cold War diplomacy, or the actions of affluent countries, including China, in the post-9/11 period. Less thought has been given to how developing countries can muster their cultural resources, or the role that public diplomacy played in the early 20th century.

To better understand these issues the current paper explores the ways in which educational reformers during the early Republic of China era attempted to advertise a rational and scientific vision of the Chinese martial arts as part of a larger effort to craft a progressive image of China on the global stage. The strategies that they employed focused on “citizen-to-citizen” diplomacy, yet they helped to lay the foundation for the better-known state led efforts to marshal the cultural appeal of the martial arts in the current era.

This presentation is structured around three brief case studies. The first focuses on the actions of a private organization from Shanghai (the Jingwu Athletic Association) which developed a talent for attracting English language press coverage of its efforts. Secondly, it examines the very first English language Wushu manual, written by a Chinese graduate student at Springfield College in 1926. Last, we look at some ways in which Chinese student organizations at several American universities used public boxing exhibitions to draw attention to political questions that they believed were critical to US/Chinese relations.

While many of these efforts were well received at the time, the paper closes by asking why they have been subsequently forgotten, and what that indicates about the public diplomacy strategies that are likely to be the most successful in the long run.

Jingwu Spreads the Gospel of Kung Fu

Prior to its defeat in World War One, the German educational system (as well as the Japanese model which drew inspiration from it) was the subject of careful study and debate by Chinese reformers and policy makers. Noting the importance of budo in Japan, and the success of more militant physical education programs in Germany, various policies were debated and accepted to introduce subjects like military drill and martial arts practice into school and university curriculums across China.[i]

The Jingwu Association, which had developed an efficient program for training its own martial arts instructor, approached this new opportunity with a savvy marketing campaign. Members of local chapters would organize events in which students, trained in their system, would visit other public schools or stage community demonstrations. These were designed to not just increase demand for the group’s services among the nation’s youth, but to also argue that the modernized and sanitized martial arts could contribute to the nation building project.

What is often forgotten is that both Chinese and Western reporters were invited to these events, and that period newspapers, even the English language ones, are full of colorful, almost always positive, accounts of Jingwu’s activities.[ii] At times, local branches would go so far as to provide translators for events or interviews. Jingwu’s embrace of feminism and nationalism were favorite topics of Western journalists. [iii]

On May 8th of 1920 the North China Herald ran a lengthy account of a Jingwu demonstration that hits on all of these themes. In the following excerpt we can see the reporter interviewing various students about their own experience within the Chinese martial arts, and relating that to a Western audience.

CHINESE GIRL ATHLETES

“During the first month we girls took to physical culture, we felt as if we were as stiff as dried bamboos and could not move.”

Such was the opinion of a young member of the Ladies’ Department of the Chin Woo Athletic Association.

The formal inauguration of this Department was held at the Young Men’s Christian Association on Saturday afternoon and a very enjoyable programme was performed. About 80 girls took part in the exhibitions. Mr. S. S. Chow, English Secretary of the Club, presided over the gathering. More than 800 visitors were present…..

Some Boxing

The Chinese boxing, however, was the feature of the day. Girls whose ages ranged from six to 30 took part in the display. With fists, feet, knives, swords, chains, clubs, staves, and what-not, they attacked each other with the fury of men in actual battle. As in all exhibitions of Chinese boxing, the girls showed that they knew how to use their feet—and use them well. They kicked their dainty little feet over their heads in such a manner as would put foreign dancers to shame. They did somersaults on the floor and in the air quite as well as any of the menfolk. “Turning the wind” jump and the “double kick” were exhibited with much grace and neatness. When two of the girls got together in a wrestling match, they went at it heart and soul. They were in some respects superior to the men. They fought in the same manner as the men and chopped “with the strength of nine.”

…..

“How did you feel after taking exercise?”—“During the first month we girls took to physical culture we felt as if we were as stiff as bamboos and could not move. Instead of remaining stiff and weak as we were before taking exercise we gradually began to grow strong, muscular, less fat, more active, and in all we found that we were more efficient. We could eat more and sleep more soundly. We can study harder, and can work for 15 or 16 hours a day without feeling the least tired. Don’t you think that proves that the exercise in beneficial to us?…[iv]

One wonders whether it was a matter of happenstance that Mr. S. S. Chow, Jingwu’s English secretary, was the officer who fronted this highly publicized women’s event. More interesting is the fact that such a group should feel it necessary to appoint a foreign language officer in the first place. In any case, the reporter from the North China Herald left little doubt as to the real benefit of Jingwu’s training. If China’s women could undergo such a transformation, there could be little doubt as to the benefit for the entire nation.

While initially published in China, such English language accounts tended to find their way into the hands of a global readership. This particular article caught the attention of Grace Seton Thompson (1872–1959), a famous American suffragette and the author of a number of popular travelogues. In 1924 she turned her literary attention to the evolving situation of Chinese women in a volume titled Chinese Lanterns. Seton Thompson briefly noted the role of the martial arts in the creation of China’s “new woman” in her volume and quoted large sections of this article verbatim and without attribution. Still, her immense popularity as a writer ensured that word of Jingwu’s female martial artists would reach a receptive Western audience.[v]

Ma Yuehan, a forgotten Kung Fu Pioneer in America

The Jingwu Association was not the only group seeking to promote an appreciation of the Chinese martial arts on the global stage. During the early Republic, physical education reform, and the place of the martial arts within it, became a hotly debated topic in China. As intellectuals came to America to complete graduate degrees, they brought these debates with them.

Perhaps the most interesting of these efforts was Ma Yuehan’s (John Mo) pioneering 1926 thesis, “A Primer on Chinese Boxing.” While this work has passed largely unnoticed by students of martial arts studies in the West, it is significant in many respects. In addition to illustrating the process by which western trained educational reformers in China were embracing wushu, it is the earliest English language translation of a complete Chinese martial arts training manual. Ma also provided us with the first English language academic study of the martial arts to be completed by a Chinese scholar and practitioner.

Those with some familiarity with Ma Yuehan’s career might find his choice of topics surprising. This important figure is better known for his interests in athletics and soccer, as well as his service as a track and field coach in the 1936 Olympics. Nor do his other English language works suggest any awareness of boxing. His 1920 B. A. thesis, for instance, discussed only the history and development of Western style physical education programs in China.[vi]

By 1926 this disinterest in the martial arts had been replaced with a keen curiosity. Ma now stated that he had been practicing the Chinese martial arts for a few years and he declared that it was time to provide a detailed discussion of these forms of hand combat to the West. More specifically, he sought to present his readers with an introduction to the Chinese martial arts and a manual for a style named xingyiquan (Mind Intent Boxing).

Yet the process of translation is never purely linguistic. Every movement across cultural and social boundaries also implies a process of transformation. Ma was intensely aware that he was presenting this work to a western audience with its own needs and interests. He even seems to have hoped that his study would inspire more scientific study of, and interest in, the Chinese fighting systems.[vii]

He states that he chose to focus on xingyiquan because of his background as an educator. Ma noted that due to its relative simplicity, this style was frequently taught in small schools across northern China that were looking for a basic physical education program. In his opinion this same simplicity made xingyiquan an ideal platform for introducing the core movements, concepts and structures of the Chinese martial arts to western practitioners.[viii]

His discussion of xingyiquan is explicitly modern and scientific in its tone. Ma did away with any notions of subtle bodily energies or “internal principals.” Instead his emphasis was on the ability of this fighting system to develop the large muscle groups and improve a student’s overall level of coordination. Nor does he appear to have viewed these movements as in any way limited to Chinese athletes. For Ma, xingyiquan was a fighting system that should be of interest to a global audience.

This does not mean that Ma rejected the historical and cultural origins of the Chinese martial arts. In the first few chapters of his work he presents a historical narrative that aligns the creation of the Chinese martial arts with the emergence of an ancient and unified Chinese nation state. This equation is made explicit in his paradoxical claims that the Chinese martial arts initially arose as a unified style in 259 BCE.[ix] This is not a date of any significance to the modern style of xingyiquan. Rather, he appears to explicitly link the development of the martial arts to the birth of Qin Shi Huang, the first Emperor of China.[x]

Ma clearly wanted his Western audience to imagine that the martial arts arose out of the ancient (and glorious) past, rather than the proximate (and much less glorious) late imperial period. In short, the Chinse martial arts were supposed to signal to the world a unified and strong, rather than a regional and fragmented, vision of the Chinese state.

Following this basic orientation, Ma returned his focus to xingyiquan. Rather than teaching the entire style (an impossible task in any short work), he outlines its basic movements and stances in such a way that a couple of friends might be able to work through the exercises and get a fair idea of the feel of this school of boxing.

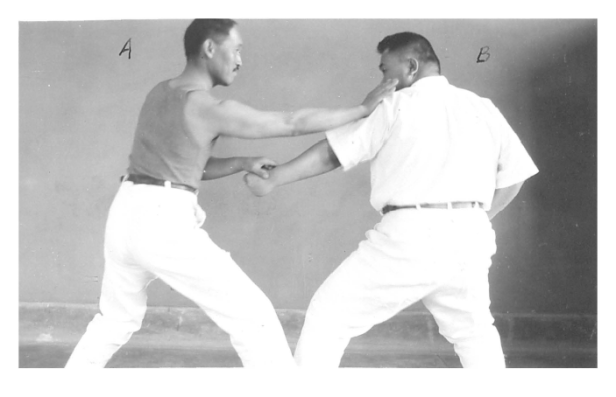

While Ma’s historical and sociological discussions must be considered very preliminary, his volume excelled in the area of practical instruction. Each of the “basic strokes” of the system were described in clear and detailed ways. These were augmented by an extensive set of original photographs (produced by the author and another student at Springfield College) which illustrated the exact points that the text outlined.

This photography also presented the Chinese martial arts as a modern athletic practice as well as a form of self-defense. Both Ma and his assistant wore western style slacks and shirts; the “traditional uniforms” that would become a ubiquitous marker of the post-war discourse surrounding the Chinese martial arts were totally absent.[xi] At the same time, Ma would point out subtle differences between Western and Chinese movements or stances that might look outwardly similar.[xii] The fighting system which he outlined, while distinctively Chinese, was showcased and advertised as universal in its appeal.

Ma’s work indicates that he expected that the Chinese martial arts would soon find the same sort of acceptance within the Western imagination that jujitsu and kendo had already won. Yet, he informed his readers, none of that could happen before China’s educational elites undertook the task of creating a single unified style for schools in both the North and South that would restore the essential unity between the martial arts and the state that had existed in the distant past. Thus Ma’s boxing was really an extension of his vision for a modern and unified China.

China’s Ivy League Martial Artists

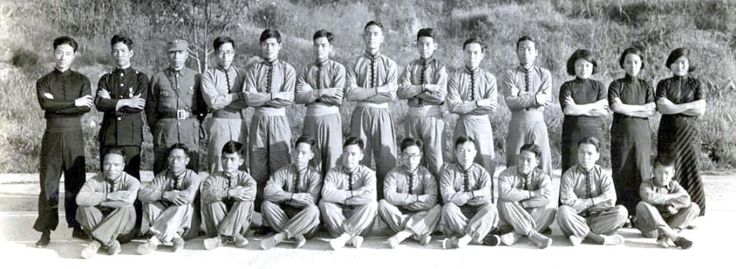

One did not have to be a professional to join in this discussion. American campus newspapers and newsletters suggest that a wide variety of Chinese university students increasingly took it upon themselves to promote and demonstrate the martial arts between the 1910’s and 1930’s. They saw these efforts as a way of sharing what they considered to be the best aspects of their national culture with curious Western students, faculty and local residents.

Rather than a centrally coordinated campaign following a single script, these community demonstrations tended to be grassroots affairs designed to fit the needs and resources of the small clubs and communities of Chinese students that could be found at almost every major Western university by the 1920s. Indeed, the newsletters that these clubs published during the early years of the 20th century suggest that along with various sorts of musical nights and other culturally focused actives, boxing demonstrations were a relatively common event on the social calendar.

Most previous studies have tended to focus exclusively on the role of immigrants and working-class individuals in pioneering the Chinese martial arts in the West during the 1960s and 1970s.[xiii] Unfortunately this post-war narrative, which focuses heavily on questions of masculinity, social violence and orientalist desires (all notable features of the era), has largely overwritten the earlier interwar era of martial arts history in the West. Today the efforts of China’s “Ivy League boxers” of the 1910s-1930s are largely forgotten.

Yet during the first half of the 20th century it was not uncommon for the various Chinese student associations to have a handful of members who stood out because of their interest or background in the martial arts. Occasionally they staged public demonstrations simply for the sake of promoting larger events on campuses. For instance, on March 15, 1935 the Cornell Daily Sun ran an article on a major fundraising event held to support the university’s crew team. In the middle of an evening of presentations and films that focused on topics like intercollegiate competition and the Olympic movement, a student named Y. S. Chan took to the stage and performed a martial arts demonstration for 175 classmates and spectators. Newspaper reporting indicates that his efforts were donated to the event as part of the effort to help raise money for the University’s popular crew team.[xiv]

Cornell had a vibrant community of international students and local newspapers suggest that such demonstrations were not uncommon. They report multiple occasions on which Chinese student groups organized boxing exhibitions for the Cosmopolitan Club, or helped to stage events designed to welcome new groups of international students to the campus.[xv] One particularly memorable “Oriental Night” saw not only a martial arts demonstration by C. M. Yu and Conant Lee, but also an exhibition of Indian fencing and martial arts.[xvi] In most cases these more vigorous events were paired with musical performances or literary discussions. The overall impression that was created was of a resolutely middle class and approachable fighting system, far removed from the superstition of the Boxer Rebellion or the social discontent that would mark Bruce Lee’s performances and the emergence of the Kung Fu Fever of the 1970s.

Yet not all the demonstrations were purely social affairs. Chinese student associations quickly grasped the popularity of their martial arts and realized that this might help them reach out directly to surrounding communities. Often these efforts were tied to then pressing questions of politics and policy.

This political tendency in student organizing was notable in times of crisis, such as the peace talks following WWI, periods of famine and flood in the 1920s, or at the outset of Japanese aggression in the 1930s. The post-WWI period is particularly interesting in this respect. Student newsletters from Columbia University (which hosted over 100 Chinese students at the time) noted an interesting confluence of events. After a holiday meeting with the City’s Chinese Consul in 1918, the students decided to form their own public relations committee dedicated to answering questions and correcting news stories that were published by the city’s press. Of course, their social gathering also included musical performances and boxing demonstrations.[xvii]

A little later the Chinese students at Cornell were also moved to address the major questions of the day. On May 10th of the same year we find a report of a public event in Ithaca NY that paired a lecture on “China and World Peace” with a boxing exhibition by K. P. Pao. Pao appears to have been acknowledged as the local expert on the Chinese martial arts during his time at the University.[xviii]

Chinese students in Illinois, also concerned with the events of the Paris Peace Conference, decided to form their own public relations committee (and they publicly urged Chinese students on other campuses to do likewise). Again, boxing and other traditional cultural practices remained central to their attempt to reach out to the public. A demonstration staged at their annual social is reported to have drawn over 200 spectators.[xix]

Foreign aid and humanitarian assistance also inspired several boxing demonstrations. In 1921 the Pennsylvania Gazette noted that the local Chinese students were organizing a gala to raise money for, and awareness of, the need for urgent famine relief in their home country. Their performances included music, Chinese opera, dance and (of course) boxing.[xx] In April of the same year the Chinese students of Cornell University also decided to host a “Native Bizarre” in an attempt to raise funds and awareness on the same issue. Their event centered around a curio auction and the creation of a “Chinese tea garden” on campus. However, the boxing exhibition (featuring both K. P. Pao and P. C. Huang) was heavily advertised in the days leading up to the event and was considered a major draw.[xxi]

Conclusion

By the 1920s martial arts demonstrations were accessible to individuals with an interest in Chinese culture near many universities around America. Largely forgotten today, these affairs were quite different from the sorts of kung fu demonstrations that would become common after the 1970s. In many ways they emerged out of a fundamentally different discourse on the Chinese martial arts and their relationship with society. These students sought to demonstrate their vision of what a progressive Chinese modernity might be.

At the margins it seems likely that these efforts had a positive impact on the public perception of the Chinese martial arts. A great many Western reporters and writers even adopted this modernizing discourse in their discussion of these fighting systems.

Still, these early efforts have largely been forgotten and replaced with narratives which place the initial “discovery” of the Chinese martial arts in the 1960s or 1970s. We can attribute the limited success of these efforts to three factors, each of which suggests something important about the limits of citizen-to-citizen public diplomacy.

First, it is difficult for individual reformers to engage in the sort of long term efforts that may be necessary to establish a “national brand” in the mind of a foreign community. Exchange students return home and even large non-profit groups like the Jingwu Association may suffer unexpected setbacks that brings their activism to an end. While government intervention in the cultural sector has been shown to face an inherent crisis of credibility, it does help to provide the level of continuity that these efforts depend upon.

Second, we need to think about what the French philosopher and anthropological theorist René Girard might term the flow of mimetic desire. By engaging in far reaching reforms of its traditional martial arts, early republic figures were signaling their desire to create a certain type of modern state, and to have their efforts legitimated on the global stage.

Yet American University students, who were already masters of qualities such as rationality and modernity, would find little new and appealing in the sorts of arts that were being displayed. In a sense the reformed Chinese systems did too good a job blending into the middle-class landscape. The Japanese martial arts were more interesting precisely because they seemed to be threat to the accepted racial and political order of the day. What captivated early 20th century audiences was the promise that they too might be able to overthrow this order. The elite Chinese martial arts of the 1920s and 30s had become almost too eufunctional?

Finally, during the 1920s Chinese martial reformers failed to build a community of local supporters who could contribute resources and sustained points of contact in the West. In many ways this was natural result of the first two points. Ma returned to China rather than teaching xingyi, and the newspaper accounts and demonstrations of the era inspired cultural interest, and sometimes even admiration, but not rabid personal enthusiasm.

To succeed, citizen-to-citizen diplomacy needs to mobilize economic and social resources in both nations, and that is not likely to happen in a situation of one-way display and performance, which is what happened in the 1920s. Rather, a new community needs to be created via the processes of appropriation and cultural translation. In the case of the Chinese martial arts, that would have to wait for post-war immigration reforms and the emergence of the counter-culture movement. It would be these two powerful forces that would flip the direction of mimetic desire in the West, effectively giving kung fu its soft power.

oOo

Notes

[i] Lu and Fan 2013.

[ii] The fact that the organization even included English language news clippings in its ten year anniversary volume suggests that they followed this coverage quite closely.

[iii] For a detailed discussion of Jingwu’s approach to gender and its progressive stance on feminism see Morris (2004), 199-200.

[iv] “Chinese Girl Athletes” North China Herald. May 8th, 1920. 342-343

[v] Grace Gallatin Seton Thompson. 1924. Chinese Lanterns. New York, Dodd, Mead and Co. 250-251.

[vi] John Mo 1923.

[vii] John Mo 1926, Preface.

[viii] John Mo 1926, Preface, 8.

[ix] John Mo 1.

[x] Gainty would remind us that Meiji era martial arts reformers in Japan had also adopted a similar rhetorical strategy of linking the martial arts to the emergence of the modern nation state through their supposed connection to the imperial throne (131-135).

[xi] This was not uncommon at the time. Many of the boxing manuals printed by reformers during the early Republic period featured models wearing athletic wear or the sort of clothing that one might expect to see in a middle class golf outing.

[xii] P. 48.

[xiii] Miracle 2016; Charles Russo. 2016. Striking Distance: Bruce Lee & The Dawn of Martial Arts in America. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

[xiv] “Crew Benefit: Y. S. Chen, Grad., Features Entertainment with Chinese Boxing.” The Cornell Daily Sun. March 15th, 1935. 1.

[xv] “Foreign Student Reception Held.” The Cornell Daily Sun. October 8th, 1934. 1.

[xvi] “Students to Present Unique Entertainment.” The Cornell Daily Sun. December 12, 1925. 6; This type of event was not uncommon. In May of 1920 the Chinese Students’ Monthly ran the following dispatch from Columbus Ohio: “A series of International Nights were arranged by the Cosmopolitan Club this year. China was asked to take the lead in the program. The club summoned her genius and presented a most successful Chinese night on February 13. Music, Chinese boxing, Chinese gymnastics, reading of Chinese literature, speech, fortune-telling and games formed the delightful program.” (63). These are typical of press accounts of cultural activities staged Chinese college students in the 1920s and the place of the martial arts within them.

[xvii] “Club News: Columbia.” The Chinese Students’ Monthly. Vol. 14 Issues 2-8 (1918). 137.

[xviii] “In appreciation of the interest of the town people of the “biggest small city” and the faculty of the University, a reception was given on May 10. The program of this occasion was very elaborate, and entertaining. An address on the subject “China and World Peace” made by D. H. Lee was especially good, and won much praise and gave much inspiration. The other interesting feature of the program was our art in boxing exhibited by K. P. Pao who was considered as “some” expert.” “Club News: Cornell.” The Chinese Students’ Monthly. Vol. 14 Issues 2-8 (1918). 504.

[xix] “Club News: Illinois.” The Chinese Students’ Monthly. Vol. 14 Issues 2-8 (1918). 505-506.

[xx] “Chinese Students Give Famine Benefit.” The Pennsylvania Gazette. February 18th, 1921. 476.

[xxi] “Chinese Students Plan Native Bazar on April 29.” The Cornell Daily Sun. 16th of April, 1921. 3; “Chinese to Give Oriental Show Friday Evening.” The Cornell Daily Sun. April 25th, 1921. 6. “An exhibition of Chinese boxing is included on the program. Boxing is said to have its inception in China, and some of the Chinese are unusually clever boxers. K. P. Pao ’22 and P. C. Huang will demonstrate their art to the audience. Among the other stunts are diabola, shuttle cock and Shuang-huan, typical Chinese novelties.” Also see the large advertisements that ran in The Cornell Daily Sun on April 15th, 19th and 27th under the banner “Humanity’s Greatest Opportunity.”

oOo

If you enjoyed this essay why not also read: The Tao of Tom and Jerry: Krug on the Appropriation of the Asian Martial Arts in Western Culture.

oOo

November 20, 2017 at 1:57 am

Reblogged this on SMA bloggers.

December 1, 2017 at 12:47 am

Reblogged this on Dim Mak Gong Fu Training Journal.