Introduction

Welcome to the sixth entry in our series of guest posts titled “Doing Research.” If you missed the first essay by D. S. Farrer (which provides a global overview of the subject), the second by Daniel Mroz (how to select a school or teacher for research purposes), the third by Jared Miracle (learning new martial arts systems while immersed in a foreign culture), the fourth by Thomas Green (who is only in it for the stories), or the fifth by Daniel Amos (who discusses some lies he has told about martial artists) be sure to check them out!

Compared to other fields of scholarly inquiry, Martial Arts Studies has a distinctly democratic flavor. Many individuals are introduced to these systems while students at a college or university and are interested in seeing a more intellectually rigorous treatment of their interests. And certain practitioners want to go beyond reading studies produced by other writers and undertake research based on their own time in the training hall. The emphasis on ethnographic description, oral and local history, as well as the methodological focus on community based collaborative research within Martial Arts Studies (itself a radically interdisciplinary area), makes participation in such efforts both relatively accessible and highly valuable. Or maybe you are a student about to embark on your first ethnographic research project? If so it pays to think about how you will approach your fieldwork.

Charles Russo is unique among the authors in this series in that he approaches this subject not as an ethnographer or academic student, but as a professional journalist. As such he brings a different perspective to the conversation, one based on the years of experience that reporters have accumulated in figuring out how to “work a beat.” In fact, doing long-term research within a martial art community is a lot like working a beat. And journalists have produced some of my favorite books on the history and nature of the fighting arts (such as the classic discussion of Tae Kwon Do, A Killing Art by Alex Gillis). Given that Russo has just completed an important volume titled Striking Distance: Bruce Lee and the Dawn of Martial Arts in America, published by the University of Nebraska Press (2016), he is well positioned to discuss the intersection of these various approaches to field work.

Working the Beat: One Journalist’s Efforts at Perfecting the Fine Art of Hanging Out

So I’m up to my elbows in cobwebs chasing down a dead man in a nearby Necropolis…and to be honest, it’s all really a lot of fun.

Let me rephrase that: I’m in Gilman Wong’s garage in the city of Colma, California, trying to find a picture of his dad – TY Wong. For almost a century now, San Francisco has buried its dead in the city of Colma, just a couple miles to the south. At present, there are about 1,500 living souls in Colma and 1.5 million dead ones. That’s quite a ratio, and driving over to Gilman’s house past the massive graveyards, it’s easy enough to daydream in the direction of a zombie apocalypse.

TY Wong (or, Wong Tim Yuen) is one of the pioneering martial artists that I profile in my book, Striking Distance: Bruce Lee and the Dawn of Martial Arts in America. A Sil Lum master who was quickly recruited by the local branch of the Hop Sing Tong upon his arrival to San Francisco, TY – along with his senior contemporary Lau Bun – oversaw the martial arts culture in Chinatown for more than a quarter century. Despite his many key contributions to the martial arts in America, TY has mostly fallen through the cracks of popular memory. So now, I’m in the graveyard city of Colma, trying to pull him out.

It’s taken me two years to get in touch with TY’s son Gilman. And after letters and phone calls and go-betweens, here we are in his garage dusting the cobwebs off of a photo from the 1940s in a broken frame beneath cracked glass…and it’s a real gem.

If you would ask who my favorite practitioner was that I profiled in my book about the pioneering martial arts scene on San Francisco Bay in the early 1960s, I’d have a hard time settling on just one person. From the old guard in Chinatown, to the innovators in Oakland, to a young trash-talking Bruce Lee, one figure was more compelling than the next. But when it comes to photographs, all of my favorites seem to involve TY Wong.

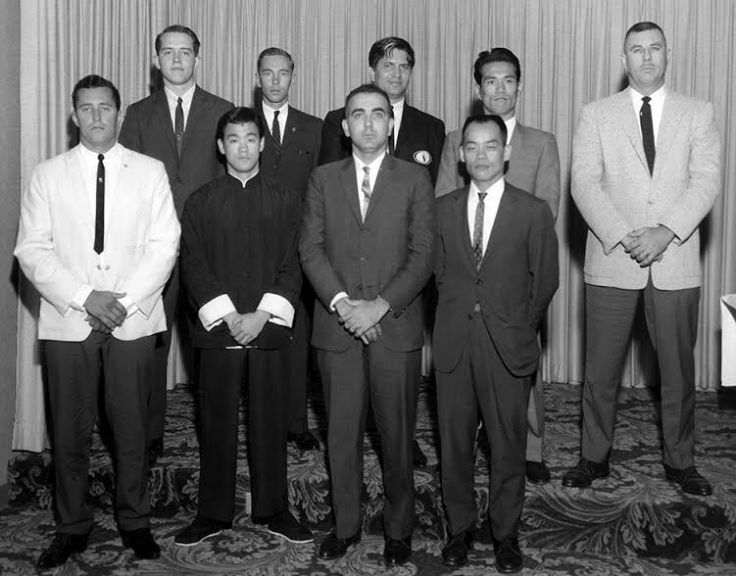

There’s the 1965 photograph of of him with seven teenage students in his Chinatown school: the Kin Mon Physical Culture Studio (or, The Sturdy Citizen’s Club). Here, TY is pictured next to his one white student at the time: Irish teenager Noel O’Brien. Beginning in 1960 with Al Novak, TY was known to accept the occasional non-Chinese student despite the prevailing exclusionary etiquette of the times.

A true martial artist, there is also the photograph of TY playing the violin in his living room (“he was self-taught,” according to Gilman). But best of all, is the image of TY at the 1928 Central Guoshu Institute’s national tournament in Nanjing, China. TY is on the right in a tai chi pose, with his teacher Long Tin Chee in the center, and senior student Chew Lung on the far left. It’s just a beautiful glimpse of martial arts history, and up to now that image has been my standout favorite.

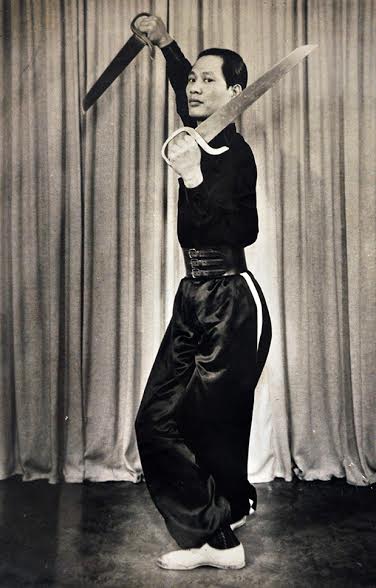

However, looking through the cracked glass at this photograph of TY, it might just be a contender for my new front-runner. It’s a parade scene from San Francisco in the 1940s, and TY is surrounded by a large team of martial artists. He stands at the center of the entire congregation all in black, holding butterfly swords. Despite the many men around him and his slim stature, TY looks quietly authoritative and formidable.

Gilman and I retrieve this image and several others from the garage, including what we originally came for – the photos from the Arlene Francis show (more on that later). We then proceed inside to talk shop for a few hours. As I said, it’s all quite a lot of fun.

Celebrated veteran journalist Gay Talese once said that good journalism is predicated on “mastering the fine art of hanging out”…which of course, is possibly the least academic sentiment ever written, though that’s not to say it’s without merit.

Working a beat as a journalist is a simple enough concept. It means to cover a particular topic thoroughly and on a consistent basis. You get to know the people, the places, the issues, and the nuance by frequently putting yourself in close proximity to them. In this sense, Talese was talking about investing enough time so that something or someone can be seen from many angles; the myriad facets beyond the cultivated identity that is projected to the world.

For my book, I applied a beat reporter’s approach to this particular era of martial arts history. I suppose that is a more formal way of articulating my efforts at perfecting the hangout. Whatever you want to call it, here are a few aspects of the approach that seem the most essential.

The Horse’s Mouth

While studying History (for my grad and undergrad) I kept noticing something peculiar. It was constantly being explained to me how important primary sources were, of seeking out the accounts of people who experienced events first-hand. Yet, there was zero emphasis on actually talking to those people. You could read their books or archived papers, but no one ever picked up the phone to speak with them directly. Once, when a classmate was discussing his questions about the aging author of a labor struggle memoir, I blurted out – “Why don’t you just call him?” The whole seminar turned around in shock and glared at me, as if I had said – “Why don’t you just assassinate him?”

Over in the journalism department, it was the opposite. My professors berated me for not having enough sources, for not trying hard enough to track people down. It knocked me out of my comfort zone, but in the long run I knew they were right. After all, you can’t ask follow up questions to a book, only to it’s author.

In 2012, tai chi master James Wing Woo published a really nice book about his career and method, titled SIFU. Woo was a perennial figure of the West coast martial arts scene dating back to the late 1930s. His book contains a short interview conducted by well-known journalist Ben Fong-Torres, in which Woo comments briefly on his time amid the martial arts culture of San Francisco’s Chinatown, including his experiences with Lau Bun and TY Wong. Upon reading this, I instantly had a wealth of questions for Woo, and living up to my history seminar point-of-view, I contacted James and was down at his studio in Los Angeles four days later. Woo answered all of my questions, explaining the delicate relationship between TY Wong and Lau Bun, the culture of Chinatown’s little-known Ghee Yau Seah (“The Soft Arts Academy”), and the quiet resurgence of opium in the neighborhood throughout the 1940s. He also conveyed some incredible stories of how TY Wong was the Hop Sing Tong’s go-to enforcer for whenever U.S. servicemen on shore leave got too rowdy while carousing the neighborhood’s Forbidden City nightclubs.

Sadly, James Wing Woo passed away just a few months after I interviewed him. I hate to think how much more information went with him.

Martial artists, even retired ones, are fairly easy to find. They are almost always tied to a school in some capacity, and tracking them down isn’t that difficult. Someone will refer you to them if you ask, and they love discussing their careers. This is not always the case with sources. Once while writing an article about the Zodiac Killer, I had to track down a former SFPD Homicide Inspector who retired on bad terms. No web site, no school or association, no interest in being found. That was difficult. Finding a martial artist is not.

Interview Off the Beaten Path

Here’s a quote you’ve probably never heard before: “People were practically lining up to fight Bruce Lee after his demonstration at Long Beach.”

That’s from Clarence Lee, a karate master who taught in the San Francisco Bay Area for more than 50 years. He was a judge at Ed Parker’s inaugural Long Beach International Tournament in the summer of 1964, and he knew the martial arts culture of the era inside out. They don’t quite make ‘em like Clarence anymore. He is now in his late 80s, has luminous eyes, stark white hair, and curses like a drowning sailor. (When I asked him about the reasons for the Bruce Lee / Wong Jack Man fight, he quickly shot back – “Have you ever heard of macho fucking bullshit?”) I don’t doubt Clarence’s opinion on Long Beach, yet I feel like I’m the only person who has ever really asked him.

In this sense, I think that some of the best and most colorful details often come from the supporting cast, as much as the lead; from the batboy, as much as the All-Star shortstop.

Take Barney Scollan for instance, who was an 18 year-old competitor at Long Beach in ’64. Although Scollan had been disqualified early in the day (“for kicking a guy in the nuts”) he anxiously hung around to watch Bruce Lee, particularly after witnessing his dynamic demo the night before in the hotel. Bruce’s actual tournament demonstration had a far more critical tone from the evening prior, and it struck Scollan as a revelation. “He just started trashing people. He got up there and began to flawlessly imitate all these other styles,” Scollan explains, “and then one-by-one he began to dissect them and explain why they wouldn’t work. And the things he was saying made a lot of sense.”

This is all a bit different from what I had been reading for years on Bruce at Long Beach in 1964. The prevailing narrative has asserted that Bruce did a bunch of fancy stunts, and was so fast and so charismatic that everyone quickly fell in love with him. For some reason, I’ve never been told that Bruce challenged the merit of everyone’s approach, and then half the placed wanted to kick his ass afterwards. There were a lot of people at Long Beach in 1964, is it possible that we’ve been relying on the same few sources over and over, and as a result have failed to grasp the complete story?

Oddly enough, it was another unlikely source – TY Wong’s student Joe Cervara – who summed this all up for me in a perfect sound bite, when he explained to me that his teacher was never fond of Bruce Lee, and considered him – “A Dissident with Bad Manners.” I’ve had never heard that quote before either.

Ask Outside the Box

So I’m sitting opposite Dan Inosanto in his office and my first question is simple enough: “Can you tell me about your early martial arts background?” To which he replies, “Yeah, so I first met Bruce in ’64, during the Long Beach….”

I interrupt, “I’m sorry, I wanted to know your background in the martial arts.”

He looks puzzled but a bit relieved, “Oh…ok. Well, my uncle came back from World War II and he started teaching me Okinawan te, they didn’t call it karate back then.”

I cringe to think how many times Dan Inosanto has been asked the same questions regarding Bruce Lee over and over and over. This predictable line of questioning is unfortunate because not only is Dan an encyclopedia of martial arts knowledge, but his CV is literally a who’s-who of early martial arts pioneers in America.

After talking about his earliest days training with his uncle, Inosanto explains his time in the service training with Sergeant Henry Slomanski, an early western karate champion who ran rough-and-tumble training sessions in the U.S. military. Slomanski is one of those often forgotten figures that played a key role in setting the stage for a thriving martial arts culture in America , and Dan Inosanto can talk at length about training with him.

We then move on to his time with kung fu master Ark Wong, and then Ed Parker. When I ask him about Wally Jay, he responds “Well, Wally Jay is sort of like my own personal hero,” before delving into the specifics of the jujitsu master’s exalted career. When I ask him about Leo Fong, he laughs and explains that by coincidence, Fong had actually been his family’s church minister back in Stockton. James Lee? Sure, he remembers James hardening his forearms by banging them against the telephone pole outside Ed Parker’s school in Pasadena. There’s a treasure trove of information here….and to think that I could have vaulted past all of this and just started with, “Tell me when you first met Bruce?”

I once read a piece by William S. Burroughs, written very late in his life, when he said that the questions asked of him by journalists and documentarians had gotten so predictable that he felt inclined to just refer them to other articles and documentaries that already contained the information. In this sense, researchers and journalists need to advance the line of inquiry beyond the obvious.

In Colma, when I arrived at Gilman Wong’s house he a had a variety of images and photo albums laid out on the living the room table, many of which I had seen before. I looked them over and asked, “Are the Arlene Francis photos in here?” He smiles, “No, but I think I have them in the garage.”

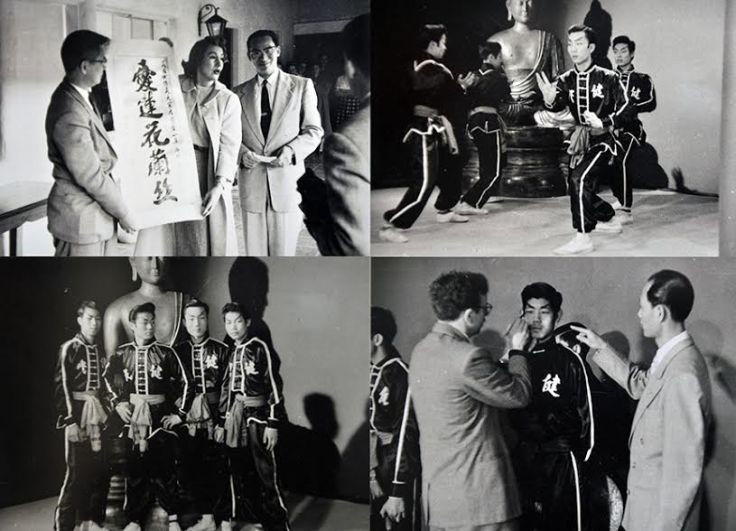

In 1955, TY Wong and his students from Kin Mon appeared on the Home show, a popular daytime “magazine program” hosted by Arlene Francis and Hugh Downs. A full decade before Americans were introduced to Kato on The Green Hornet, TY and his Kin Mon students had performed kung fu on NBC. Kin Mon’s appearance on Home is significant not only as a milestone in American martial arts (and broadcast) history, but as yet another prime example of TY evolving the culture beyond the old Tong code of not exhibiting the Chinese martial arts to the non-Chinese.

I don’t think Gilman had ever thought of digging up those particular photos, so it took an alternative line of inquiry to unearth them.

The Myth of the Mundane

History isn’t boring. It only seems that way when we’re not looking hard enough.

Think about Colma, for instance. Most people outside of the San Francisco Bay Area have probably never heard of this quiet town two miles south of one of the more colorful cities in the world. Even still, it’s a super interesting place. Consider this: traffic problems in Colma are typically caused by funeral processions. In fact, residents receive text messages to warn them of particularly large ones.

Some of the most notable of Colma’s (deceased) residents include Joe Dimaggio, Wyatt Earp, and William Randolph Hearst. Many of those who died prior to 1920 were originally buried in San Francisco, before they were (in all-too-modern fashion) priced out of the city’s real estate market, and then relocated to Colma during the middle part of the century.

The advantage of steady beat reporting is that it inevitably shakes the more fascinating details from hiding, even with topics that seem mundane on the surface. And while this can often require a journalist or researcher to take frequent trips back to a certain location, or numerous follow-up interviews with any given source, it seems to always render far more compelling material than first expected.

I leave Gilman Wong’s home with some photographs and several pages of notes. It’s all excellent material that has exceeded my expectations, from the Arlene Francis photos to the image of the 1940s street scene, to the subtle nuances of this history that Gilman has conveyed to me. In this regard, the beat has rendered some great results.

If I am in fact getting better at “hanging out,” it is due to some of these approaches that I have learned over time. And in case I lost you on all the graveyard talk (or, you just got caught up staring at TY’s butterfly swords), here is a recap. First and foremost, when it comes to sources, make a wish-list of who you would ideally like to speak with and then pursue each of them individually until they tell you – “no.” (And then politely pursue them a bit more.) The more primary sources the better. Next, look to speak with the fringe players as much as the principal characters, they will give your work unique details and nuance. Do your homework on what is already out there, and ask questions that advance the topic forward. If you need to cover well-tread material, find a new angle at approaching it. Finally, remember that even the most mundane topics can render fascinating details if you invest the time and look hard enough.

As the graveyards stream by on my right, I feel like TY Wong’s legacy is slowly ascending from obscurity. TY is buried out here. So is Lau Bun. I drive out of Colma fascinated with the people and places this history has presented to me. When it comes to the fine art of hanging out, this is easily one of the best beats I’ve had the good fortune to cover.

oOo

About the Author: Charles Russo is a journalist in San Francisco. He is the author of Striking Distance: Bruce Lee and the Dawn of Martial Arts in America (available July 1st from the University of Nebraska Press). For more photographs and materials related to the book, see the Striking Distance Instagram account (@striking_distance) or the Facebook page.

oOo

May 6, 2016 at 3:32 am

Fascinating piece, touching on key points of historical research (ask the locals/eye-witnesses!). Many thanks.

February 8, 2022 at 3:17 pm

Great read! Thanks Charles for your thoughts. So glad you were able to talk to James Wing Woo and get some of his stories. I’d love to read the interview in full if you could ever publish it.