The Professor: Tai Chi’s Journey West. First Run Films. 2016. Directed by Barry Strugatz. 72 minutes.

Click here for the Webpage.

Click here for Facebook.

“The Professor” premieres in Los Angeles on May 6 and in New York City on June 9.

Review

Learning is a matter of desire. The transmission of complex systems of knowledge cannot be forced. As such, when we attempt to explain the transmission of a martial art we are always faced with two puzzles. Why does the teacher desire to share it? Second, why (and what) do the students actually desire to learn?

Why did they seek out this individual in the first place? How do these desires shape the process of transmission and the always tricky business of cross-cultural translation? How do the needs and wants of a teacher feed into the needs and desires of the students?

As I have researched the history of the Asian martial arts I have come across numerous biographies, interviews and essays all hoping to record the lives and contributions of great teachers. Unsurprisingly most of these are produced by students. Yet (leaving debates about lineage politics aside) most of these accounts have very little to say about the community of students that surrounded the teacher and supported them.

Instead esteemed masters are often cast as remote geniuses, almost unapproachable in stature, whose abilities lay beyond the comprehension of mere mortals. Alternatively a teacher may be seen as the careful curator of a vast lineage tradition; one who regulated the clan’s relationship with the past and their martial ancestors. These sorts of popular folk histories are common and they tend to follow certain, almost universal, patterns. Prof. Thomas Green, in his work on folk history in the martial arts, has explained what sorts of work this type of knowledge does within the community.

Rarely do we come across accounts that take as their central object a teachers relationship with their students. Perhaps this is because in a traditional Confucian context the nature of such relationships were assumed to be universal. Yet one of the things that I have always found most interesting (and inspirational) about the Chinese martial arts is the close personal relationships that often emerge between teachers and students.

In truth the structure and nature of these relationships (even with a “traditional” setting) have always been highly variable. This is critical to understanding the learning process. The categories “teacher” and “student” are mutually constitutive. One cannot exist without the other. Martial arts, as a social system, only appear when both are present.

To ask the question, “How did taijiquan travel to the West?” is to enquirer about the most deeply held desires and relationships of two sets of individuals. Yet it seems that most of our popular discussions overlook these questions as they focus strictly on the biographical details of the masters.

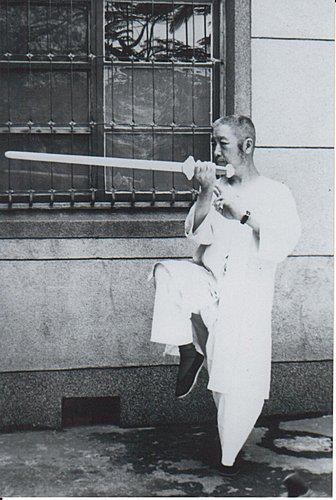

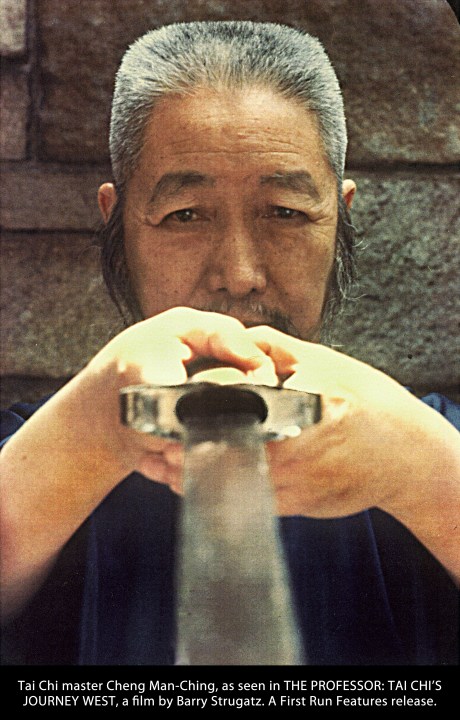

Barry Strugatz’s documentary, The Professor: Tai Chi’s Journey West (2016), employs a very different approach. This project, produced by First Run Films, takes as its subject the life and career of Zheng Manqing (Cheng Man-ch’ing, 1902 – 1975).

Born into relatively challenging circumstances in Zhejiang Province, Zheng went on to become a highly accomplished polymath, sometimes referred to as “The Master of Five Excellences” due to his talents as a painter, poet, calligrapher, traditional medical doctor and martial artist. In addition to these pursuits Zheng was also an author and a revered teacher.

Over the course of his varied career he held numerous academic and cultural posts. Zheng got his start in life as a professional painter (specializing in floral subjects) and staged multiple important shows throughout his career. Yet, as Douglas Wile has noted, it was his great professional flexibility which allowed him to remain relatively successful and well connected throughout the turmoil of the mid 20th century.

In the current era Zheng is best remembered as a talented and prolific teacher of Yang style Taijiquan. He became a student of Yang Chengfu sometime around 1930 and is reported to have ghostwritten the actual text of his classic work Essence and Applications of Taijiquan. Zhang associated with such luminaries as Chen Weiming and other leading lights of the taiji movement. He is widely remembered by his students for his unique, highly cultured, approach to taijiquan and the creation of his own short form.

Zheng published two early English language texts on taijiquan (one with the assistance of R. W. Smith) and he taught students in China, Taiwan and the United States. It should be noted that his approach to taijiquan also proved to be quite popular in South East Asia.

After arriving with his family in New York City in 1964 Zheng (with the help of a few other individuals such as T. T. Liang and Robert W. Smith) did much to spread and popularize his approach to Yang style taiji in the West. While a politically conservative figure he found himself thrust into a period of American social upheaval. In his time in the US Zheng witnessed the civil rights movement, anti-Vietnam War protests and the flowering of the 1960s counter-cultural period.

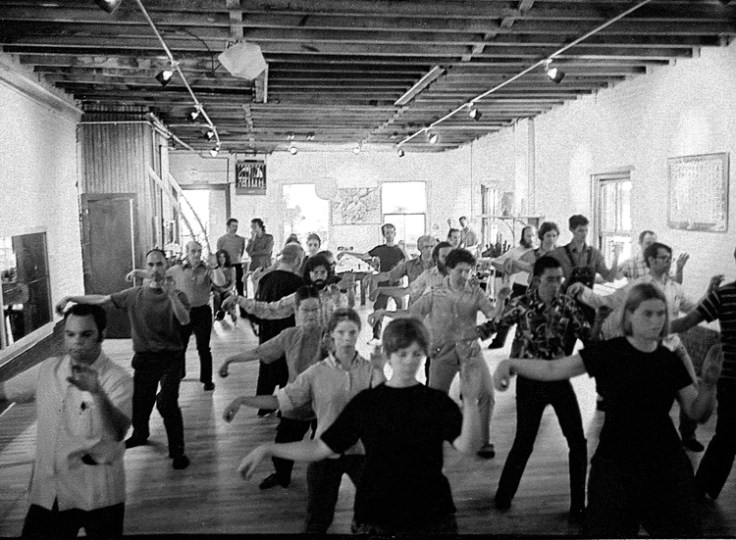

Yet this volatile era proved to be fertile ground for Zheng’s teachings. Acting as a sort of cultural missionary he reached out to a wide range of pre-existing martial artists, hippies, and those who were simply curious about Chinese culture. It was among these groups that he established his school.

While Zheng chose to reside on Riverside Drive (near the library at Columbia University where he conducted some of his research), at his school in Chinatown he taught classes on the Taiji form, push-hands and fencing. He even offered instruction in more cultural pursuits, such as calligraphy. Zheng also saw patients and dispensed prescriptions for traditional Chinese medical treatments.

The Professor’s career was diverse and spanned continents. He was an undeniably important figure in the spread of the Chinese martial arts to the West, yet he is not without his detractors. And there are certain questions that still linger about important details in his biography. Yet in comparison to most other 20th century TCMA masters much has already been written on Zheng.

I have sat down multiple times to write his biographical sketch for the “Lives of the Chinese Martial Arts” series, but every time I have stopped myself before going forward. Maybe this documentary will finally inspire me to produce something more comprehensive on Zheng’s life and career. Yet my background is not in taijiquan and every time I have approached the task I have been deterred by the amount of material out there as well as the passion that Zheng still generate in the martial arts community.

Barry Strugatz seems to have sidestepped these issues by approaching Zheng in a highly focused way. Rather than attempting to tell the entire story of his involvement with Taiji, he focuses only on the last phase of his career, after the move to New York. Nor does his film even attempt to chronicle this late period in a systematic way.

Instead the narrator’s voice is reduced to a half a dozen informational screens presenting important details of Zheng’s life at key moments of the documentary. Between these markers the audience’s attention is monopolized by extensive interviews with a number of Zheng’s surviving students from the New York period. The viewer is not presented with a single authoritative statement of Zheng’s life, or even a single extended reminisce.

Instead we have the voices and memories of a large number of students, each revealing the essence of their personal, educational and martial encounter with Zheng. As you would expect these narratives support each other in places, and at other times they diverge.

Some accounts stress his wisdom and virtue, almost to the point of hagiography, while others go on to note that Zheng was not a saint, but was in possession of an ego just like any other human being. Some of his students recall him as an unassuming individual, while to others he was a magnetic and charismatic force. The benefit of this approach is that the relatively unfiltered memories offer many glimpses of Zheng’s school and his teaching methods. Yet, as is always the case with memory, when one focuses on a single detail for too long Zheng fades from view. Viewers looking for a definitive statement of who he was, and what he accomplished, are likely to be disappointed.

How could it be otherwise? By the time one reaches the end of this film it is clear that this was never a statement on Zheng so much as it was an exploration of the shared community of desire that existed between him and his students. This, I think, is the most interesting aspect of film. What it lacks in biographical detail it make for in the rich portrait that it paints of life in New York for early students of the Chinese martial arts before Bruce Lee and the explosion of the Kung Fu Fever.

The image that emerges here is of a complex community, one split between crew cut wearing martial artist coming out of disciplines like judo and karate on the one hand, and long haired hippies looking for a physical expression of the counter-cultural impulse on the other. Both groups looked to Zheng and saw in him the promise of fulfilled desires, possibly even for a new sort of community.

Nor did these competing cultural currents always sit well with Zheng’s Chinese supporters. One of the most interesting exchanges in the film is a debate as to whether his school was expelled from one of its early Chinatown locations because the property’s owners were offended that Zheng was teaching black and white students. Or, as Carol Yamasoki asserted, was the problem that he was teaching hippies whose values were seen as offensive to the more conservative local Chinese community?

It is fascinating to watch the development of a persistent narrative throughout this film that Zheng was forced to “break free” from the oppressive and at least tacitly racist Chinese community in New York so that he could spread his art to outsiders. Given his conservative nature one wonder’s what Zheng himself would make of these accounts. Ultimately we will never know. Yet in telling them his family and students seem to be claiming for him a very specific sort of Chinese identity, one that is fully compatible with progressive American life and which positions itself against the superstitions and parochialism of China’s past.

One of the film’s more surprising moments came in the opening sequence. Here the camera focuses on a black and white image of Bruce Lee giving a televised interview in which he expounds briefly on the nature and goals of taijiquan.

That one would turn to Bruce Lee as the opening act for Zheng Manqing seems a bit odd. Lee never claimed expertise in taijiquan, and given his complex relationship with his father (who was a taiji exponent) one suspects that you would not want to pursue this line of questioning very far. As I watched this I found myself thinking “Couldn’t we have found a more “proper” voice to introduce taijiquan?” Indeed, I kept coming back to that thought for days after watching the film.

If this was a feature length documentary about the history of taiji in the West, or even the career of Zheng Manqing, the answer would probably be “yes.” But if we look a little deeper it becomes apparent that this is not a film about either of these things. Indeed, the actual stars of the show are Zheng’s many students.

Or perhaps its focus is the cooperative community that sprang up between a teacher and a group of students drawn together by deeply felt, mostly unarticulated, desires. A desire for martial mastery. A desire for stability and peace in a period of turbulence. A desire for esoteric knowledge and the promise of truly ancient wisdom. A desire for an authentic encounter with Chinese culture. A desire for adventure and exploration. A desire to experience a profound human connection, and through that to find self-worth. A desire for an acceptable vision of authority. A desire for authentic community.

Bruce Lee and Zheng Manqing may seem to be two entirely different types of martial artists. Their incompatibilities extended far beyond questions of style. These were men of unequal age who were the products of radically different life experiences. And yet they both found themselves enmeshed within this same web of desire. Their contributions to the development of the martial arts in the West were filtered through these desires. Lee’s standing within the taiji community ultimately does not matter as, by including him, we are reminded that he was an inspiration to many of the individuals who found themselves drawn to Zheng’s teaching during the later 1970s (R. W. Smith’s spirited protests notwithstanding). Thus another aspect of the community is revealed through this editorial choice.

Some viewers, I suspect, will argue that Strugatz has drawn the frame around his subject a little too tightly. Even if we accept the choice to focus on Zheng’s relationship with his students, one cannot help but notice that some of the most interesting personalities are conspicuous by their absence. Specifically, the Professor seems to be remembered only from the perspective of his New York students.

Even other students and disciples in the US do not make the cut. Robert W. Smith did much to promote Zheng’s standing in the US through his various publications and teaching efforts. Smith first met Zheng while stationed with the CIA in Taiwan. As such their association predates the period of this film. Yet I was surprised that the only mention of Smith was a memorial note at the end of the credits.

Likewise William C. C. Chen, another important Taiwan era student (and a fixture in the NY taiji scene) was notably absent. And one wonders what opportunities were missed by not discussing T. T. Liang and his notoriously complex relationship with his teacher.

This documentary appears to present a wealth of images of Zheng Manqing. And there is a lot to be said for the strategy of self-consciously approaching a teacher from the perspective of their students. Yet even here we are seeing only a small slice of the number and types of relationships that existed. Once again, as we focus too intently on Zheng, dressed in his scholarly robes, “The Professor” seems to recede from view.

It may simply be that it is impossible to present a comprehensive portrait of any individual who could legitimately be called a “Master of Five Excellences.” Yet Strugatz has painted a compelling image of him at the center of a specific community at a critical time and place in the history of the United States.

This film shines brightest as a primary document recording the needs and desires that drove individuals to seek out the Chinese martial arts in the 1960s and 1970s. It is also an important remembrance of a critical period in the dissemination of taijiquan in the West. For students of Zheng’s taijiquan it will be mandatory viewing. While it may not resolve all of the riddles of the Professors’ life it is sure to inspire new discussion. And students of martial arts studies will find in these conversations new insights about the unique balance necessary to culturally translate a martial art while forging a new community around it.

oOo

If you enjoyed this review you might also want to read: Sugong – Exploring a Shaolin Kung Fu Tradition

oOo

6 Pingback