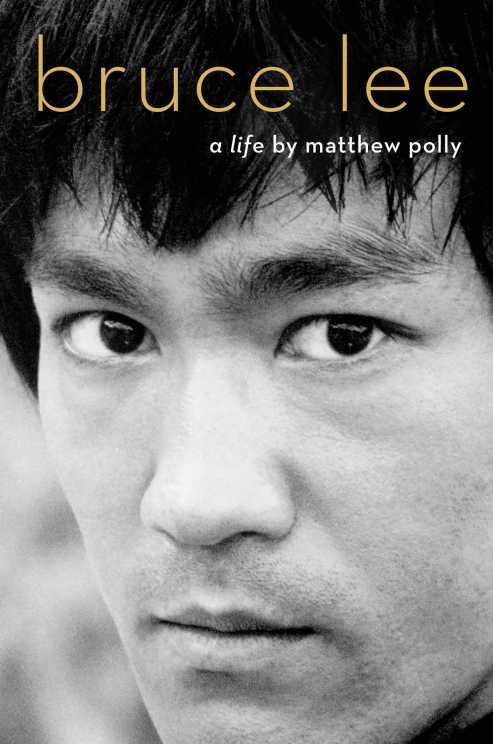

Matthew Polly. 2018. Bruce Lee: A Life. New York: Simon and Schuster. 656 pages. $35 USD.

Introduction

Matthew Polly is perhaps the best known and most popular author writing on the martial arts today. His first two books took us on a whirlwind tour of life in the Shaolin Temple and MMA training for the octagon. His latest project is a painstakingly researched biography of the famed actor and martial artist, Bruce Lee. This book has already generated a lot of public discussion. I don’t think that I am going out on a limb when I assert that this volume is likely to go down as the definitive Bruce Lee biography. I am thrilled that Matthew was willing to drop by Kung Fu Tea, and talk in some detail about both Lee’s life and the process of biographical research. Enjoy!

oOo

Kung Fu Tea (KFT): Lets start our conversation at the end, which is where your biography begins as well. Bruce Lee dies. And the cause of that death has inspired huge amounts of speculation over the years. Not to be out done, you advance your own, well-reasoned and very plausible, argument that Lee essentially died of heatstroke. I find that interesting as it’s the sort of thing that could actually happen to anyone. It is tragic whenever someone dies from an event like this, but it also strikes me as essentially an accident. It is like hearing that someone was hit crossing an intersection. We tend to avoid ascribing moral weight to random events. As such, I suspect that some readers might not be satisfied with such a “common” cause of death.

So lets talk about the significance of Lee’s death. Why does it still matter to people, 45 years later, how Lee died? And ultimately does having an answer change anything about our assessment of either his life or career as a martial artist?

Matthew Polly: There are two things everyone I’ve met on this journey knows about Bruce Lee: he was an expert at kung fu and there was something fishy about his death. Linda Lee has written that the question she gets asked the most is: “How did Bruce die?” His death is tied up with his legend in the public mind. We have a special place in our culture for celebrities who die young at the peak of their powers (James Dean, Marilyn Monroe). And part of Lee’s iconic status rests on that fact that we were never able to watch him grow old. More importantly, people find it difficult to let someone go if the cause of death remains a subject of controversy (JFK). It’s a wound that people keep picking at. It matters in Bruce’s case specifically because it remained a mystery for so long.

This made it particularly hard for Bruce Lee biographers over the years, because they had to end their books on an open question. Maybe it was an aspirin allergy? Or maybe it was the Triads? Or maybe it was a curse? Maybes are not a satisfying conclusion to a story.

How someone dies, particularly if they die young, makes a difference in how we understand their story. Suicides, like Robin Williams, cast a pall and force the biographer to look back into a life for clues of depression, etc. A murder would raise questions like: “Was Bruce reckless? Did he offend the wrong people?” Heat stroke can be random, but there are risk factors associated with it. In Bruce’s case, they were lack of sleep, weight loss, and having his armpit sweat glands surgically removed a few months before his death. He collapsed once and nearly died of heat stroke on May 10. Instead of taking a break or a vacation, he dove back into work. If the heat stroke theory is correct, then Lee’s relentless drive for perfection made him vulnerable and fate did the rest. His story becomes a parable of someone who paid the ultimate price to achieve his ambitions. So yes, how someone dies can very much change the way we perceive their life.

KFT: Let me now toss out another impossible question for you. You are no stranger to the world of professional martial arts. You lived at the Shaolin Temple before it was cool. You trained in Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) and fought in the octagon. In your assessment, how good of a martial artist was Bruce Lee? Or is that the sort of question that those of us who never had a chance to touch hands with him can never know the answer too?

Matthew Polly: This is everyone’s second favorite question about Bruce after “why did he die.” You can never know for certain how good someone is unless you can exchange with them in person, but you can make some general observations even about people you have never met. The important factor is to break the “martial arts,” which is a huge category, into what I consider to be its four subsets: 1) no-rules combat (warfare, street fighting); 2) combat sports (boxing, kickboxing, wrestling, MMA); 3) stage combat (kung fu movies, Pro Wrestling, Peking Opera); 4) spiritual combat (Zen, Taoism, the quest for enlightenment).

As to the first category, Bruce’s mother style of Wing Chun was primarily a stripped down street-fighting art form, as was Lee’s later invention of Jeet Kune Do. Wing Chun appealed to him because street fighting was Bruce’s favorite extracurricular activity. By all accounts, he was excellent at it. He certainly put in enough practice. One of the main reasons he had to leave Hong Kong is because the police told his mother if he didn’t quit picking fights they were going to throw him in jail. I would say he was an elite street fighter, particularly for his size.

As for the second, Bruce had very limited experience with combat sports: he competed in one boxing tournament as a teenager. He didn’t like the rules associated with combat sports. I think he could have been very good if he chosen to pursue a particular combat sport, but he didn’t, so he wasn’t.

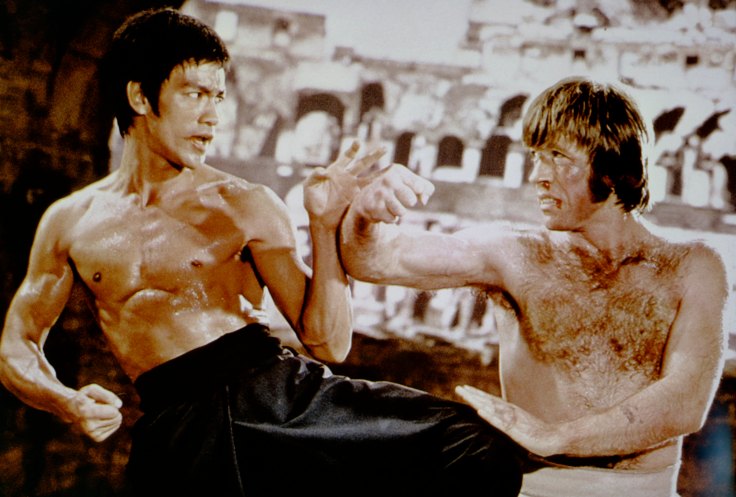

It is the third category where I believe Bruce was the best the world has ever seen. His legend rests almost entirely on his performances in four kung fu flicks, which were so magnetic, graceful, and ferocious that they inspired millions of young boys and girls to take up the martial arts. I know, because I was one of them. Jackie Chan is a more acrobatic performer and Jet Li has mastered far more techniques, styles, and weapons, but no one has ever seemed deadlier on screen than Bruce Lee.

As for the fourth, Bruce Lee was a seeker. He was deeply invested in the spiritual side of the martial arts. It’s one of the qualities that makes him so fascinating. In my view, he was on the path and headed in the right direction, but when he died, at the age of 32, he still had a ways to go, as do most young men. If he had been granted another 30 or 40 more years of life, I think he would have found the inner peace he was looking for.

KFT: I wonder if I could get you to say a few words on genre. Obviously, your voice and personal experience comes through in all of your books. But as I think back on them they are different works. American Shaolin really strikes me as a story of place. Tapped Out, while a personal journey, is also an exploration of a practice and a fighting culture. So why, for your third act, did you choose to journey into the realm of biography? That must have called for a very different approach to researching and actually writing a book?

Matthew Polly: The reasons for the shift were largely practical. While training MMA for my second book, Tapped Out, I ended up with a broken nose and cracked ribs. For my next project, I wanted to find a topic that didn’t involve me getting punched in the face.

My first two books were written from a first person perspective in a gonzo style. I wanted to be the P.J. O’Rourke of martial arts writing. For a biography of Bruce Lee, I had to reinvent my prose style and switch to third person. It took several drafts, and each one involved editing myself out of the main text and sublimating my sense of humor. A lot of the first person storytelling and jokes were removed to the end notes, which I think of as the DVD extras. As I rewrote and rewrote over a three year period, I would remind myself, “This is not about you; it’s about Bruce. He has an amazing life story. Don’t get in the way of it.”

I also feel it is important for the prose style to match the subject. Bruce preached simplicity, directness, and economy as the tenets of his martial arts style. I tried to keep those principles in mind when writing about him.

KFT: Biography, as a genre, is something that has acquired a sort of checkered reputation among both academic historians and literary critics. Roland Barthes rather famously characterized it as “A novel that dare not speak its name.” And others have gone even further in asserting that by forcing us to find significance in the random occurrences of a life based on our foreknowledge of how it is going to end, all biography is a type fictional (if often very well researched) writing. One simply cannot package and tell another human being’s story without utterly transforming it.

I have certainly written a fair number of biographical sketches in my own academic work (including a short treatment of Ip Man), so I have my own thoughts on this issue. But I was wondering how you would respond to these charges. Can we capture not just the events, but the texture, of another human being’s life? Or, in some ways, is all of this asking the wrong question?

Matthew Polly: Once when I was sitting in Princeton’s student union I overhead a Comp Lit grad student say to some young coed he was trying to impress, “Clarity is hegemonic.” That was the moment when I realized I was never going to become an academic. In my opinion, if you can’t express an idea in a way that an intelligent, educated person can understand, then you don’t really understand the idea yourself. I would like the months of my life back I wasted trying to decipher the writings of Barthes, Foucault, and Derrida. Perhaps biographies resemble novels, because so many novels are just biographies with fancier prose and more imaginative plot lines.

Secondly, who says a life is a random occurrence of events with no causal connections and no meaning that can be derived from knowing how it ends or how it began for that matter? That kind of argument strikes me as a kind of flippant nihilism. Of course, adapting any human experience—a life, a war, a social struggle—into a book or a film involves the use of elements associated with fiction, like compression and scene setting and themes. The question with biographies is not: “Does this one exactly capture the life,” but “how close to the truth does it get?” There have been over a dozen biographies written about Bruce Lee. If you read all of them, as I have several times, it is pretty obvious which ones are better representations of his life and which ones are worse.

KFT: I once had a conversation with Charlie Russo (who has written extensively on the history of the Chinese martial arts in the Bay Area) about getting good research interviews. I personally have always believed that my prior experience as a martial artist gives me a degree of insight into what sorts of questions are interesting, or what answers might be plausible. Still, I am aware that being enmeshed within the complex social world of the martial arts has probably closed certain doors to me.

I have always been impressed with Charlie’s ability to open doors and get interviews. I suspected that as a non-practitioner he might be able to more credibly explain that he is just looking to tell a neutral story of a neighborhood. What was your experience? What was one time when you benefited from your extensive martial arts background, and when may it have complicated things?

Mathew Polly: First off, let me say that I love Charles and adore his book Striking Distance. It is one of the few well-written, well-researched books about Bruce out there. Charles and his book were extremely helpful in my research and I relied upon his work a great deal in covering the Bay Area period of Lee’s life. Every Bruce Lee fan should buy his book.

But to address the question, my experience is that the type of person who prefers to tell his story to a non-expert is usually a con artist. Honest people prefer an expert, because they don’t have to explain as much. So for example, Wong Jack Man and his students, like Rick Wing who wrote Showdown in Oakland, have been trying to sell a lie for fifty years—WJM really won that fight with Bruce Lee. They even got Hollywood to go for it with Birth of the Dragon (2016), which is nearly as inaccurate a depiction of the match as Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story (1993). Anyway, I got Rick Wing to agree to an interview with me until he found out about my background as a martial artist and then he backed out of it. I’m still amused by the irony that Rick tucked tail and ran from me just like his master Wong Jack Man did from Bruce.

For almost everyone else, my background as a fairly serious martial artist and a reasonably successful martial arts author was a benefit. They knew they weren’t wasting their time with some fanboy who was going to write something that no one was ever going to read. I’m proud to say that my Bruce Lee biography is the first one ever put out by a major New York publishing house (Simon & Schuster). My background also proved particularly useful in an interesting way with Betty Ting Pei. She’s deeply into Buddhism and the fact that I had lived in a Buddhist Temple in China was a connection she brought up repeatedly during our series of interviews.

KFT: A lot of the press coverage of your book has tended to dwell on its discussions of the more sensational aspects of Lee’s life, such as his drug use or various extramarital affairs. But one of the things that didn’t seem to come up all that much in your discussion were the persistent accusations of plagiarism that have followed Lee through the years. Obviously, some of this stuff is difficult to deal with as one rather doubts that Lee ever intended to have his private notebooks published after his death. Yet the college philosophy paper articulating his now famous “be like water” philosophy, in which Ip Man helps him to overcome difficulties in his Wing Chun, is clearly dependent on a published work by Alan Watts on hitting, and then overcoming, a conceptual wall in Judo. I guess that raises two questions. First, how do you deal with a massive amount of misattribution within discussions of Bruce Lee’s philosophy. And second, what insight, if any, can we can gain about Lee’s personality from his rather liberal appropriation of Alan Watts?

Matthew Polly: James Bishop, who dedicated a large portion of his book, Bruce Lee: Dynamic Becoming, to the subject of misattribution and plagiarism in that college essay, has already emailed me repeatedly on this topic. When I was at lunch recently with Richard Torres, who teaches JKD and knows his Bruce Lee history, he pulled out Alan Watts’ book with the appropriated sections underlined. And now you bring it up. In journalism that’s called the rule of threes.

Clearly in retrospect, I should have either cut the college essay or addressed the “similarities” in the main text or at the very least an endnote. I let it slide because I had written earlier in the book that Bruce was a terrible student who often paid classmates to do his homework for him. I also happen to believe that, while Bruce borrowed language and imagery from Watts, he was genuinely trying to describe a similar spiritual epiphany. But the issue still bothers me, and if I have a chance to release an updated version I will address it more directly.

The misattribution topic is different as you noted. For readers who may not be aware, Bruce wrote down quotes he liked in his private notebooks without including the names of the writers, because he knew who they were. After he died his notes were published and these quotes from authors ranging from Chairman Mao to St. Augustine were misattributed to him. They now seem to live in perpetuity as “Bruce Lee Quotes” on the internet. My view is this was not Bruce’s fault, so I dealt with it in an endnote.

What does the fact that Bruce cheated in grade school and plagiarized at least one essay in college tell us about him? As I repeatedly pointed out in my book he was a hyper-competitive person who was not above bending the rules to achieve his goals. One of the anecdotes I tell is how Bruce asked Chuck Norris to gain twenty pounds so Norris would be fatter and much slower than him on film. I got into a debate with John Little, who fact-checked the book for me, about this story. He doesn’t believe it ever happened. My response was: “Come on, John, we both know Bruce would do whatever it took to win. That was a core tenet of JKD, which he explained to the protagonist of Longstreet when Lee taught him he should bite in close-quarters combat. He repeated the lesson when he bit Robert Baker in Fist of Fury.” Children are taught not to bite from an early age. Students are taught not to cheat. Bruce didn’t like rules or being told what to do. He liked the win. It was both a character flaw and strength. He never would have become the first Asian American male actor to star in a Hollywood movie if he hadn’t possessed such a relentless drive to succeed.

KFT: Martial arts were personally very important to Bruce Lee, and they consumed a huge number of hours within his unfortunately short life. And yet when I read your biography I constantly got the sense that they are slipping into the background, that something else was always taking priority. Lee’s passions notwithstanding, most of this book seems to be about things not directly related to the martial arts (e.g., his acting career, family struggles, etc…).

As I thought about this I started to wonder whether this was a reflection of who Lee was. Was Lee basically a professional actor (from childhood) who had an interest in martial arts? Or is this difficulty in capturing his personal discipline more of a reflection of the essential limitations of contemporary biography as a genre?

When we tell the story of someone’s life, things are supposed to happen. Events move towards an inevitable endpoint (ergo Barthes’ prior objection). And yet the reality of serious martial arts training is that outwardly, very little appears to happen at all. Every day in the gym looks similar to the one before, and the one that will come afterward. Structure and consistency is one of the things that makes martial arts training attractive to some people. But does that sort of monotony also tend to marginalize an aspect of someone’s life when we tell their story?

Matthew Polly: The answer to this question is fairly simple: it is a reflection of who I think Bruce Lee was based on my research. I have a lot of experience writing about the tedium of martial arts training and finding ways to make it interesting to readers. I dedicated exactly as much space to it as I felt it deserved in proportion to his other interests. This is a prime example of the legend not corresponding to the reality. Bruce Lee was an actor first, who became obsessed with the martial arts and then merged his two passions to become a martial arts actor as an adult. His father was an actor. Bruce faced his first movie camera at two-months of age. By the time he was 18 he had appeared in nearly twenty films—none of them kung fu flicks. He didn’t take up the martial arts until he was 16. He only taught martial arts in America, because he didn’t believe he could get an acting job as an Asian in Hollywood.

The second a Hollywood producer called him he dropped martial arts instruction like a hot potato and only took it up again after the Green Hornet was cancelled and he couldn’t get another paying gig. Even then, he focused primarily on teaching celebrities in the hopes that they would help advance his acting career, which they did. And as soon as his film career caught fire he closed down all his martial arts schools. When Bruce wrote down his “Definite Chief Aim” in life, the first line was: “I will become the first highest paid Oriental superstar in the United States.” He never mentioned any goal associated with the martial arts. Because people only watch his last four films and not his first twenty, they believe he was primarily a martial artist. But Bruce was an actor who became a great martial artist. Chuck Norris was a great martial artist who became an actor. Chronology matters. It is one of the main reasons Bruce is more convincing on film than Chuck.

©JUSTIN GUARIGLIA

WWW.EIGHTFISH.COM

KFT: I wonder if you could talk a bit about your research methodology for this book and maybe give a bit of advice to graduate students or amateur scholars who are reading this. My training is in the field of Political Science, and while we interview politicians for our research projects, we rarely ever use the things they tell us as primary sources of data. Our baseline assumption (well supported by years of experience I might add) is that they will just lie to us about any important or controversial topics. And, in a sense, I guess it is understandable. The line between studying politics and becoming involved in politics can be pretty thin. Our basic rule of thumb when doing research is something like “contemporaneous documentation or it didn’t happen.”

For better or worse, most regular people don’t document their home life, emotional states or career choices, basically all of the things that we really want to know about in a biography. Occasionally we get lucky and find letters, but you had to do a lot of interviews for this book. How did you structure your interviews with an eye towards get reliable responses and (just as critically) how did you go about assessing the credibility of the resulting data?

Matthew Polly: Someday you’ll have to explain to me how you got from Political Science to Wing Chun. But to get to your great and complex question, here’s a few pointers I’ve picked up along the way. First, as with any investigation, be it a biography or Robert Mueller’s Russia probe, the key is to gather all the documentation first and become an expert in it. That way you know when someone is telling you something new. Then you can isolate the new material and poke at it until you decide if it is true or false.

Second, if you know a subject cold you can gauge the overall veracity of the person you are interviewing. For example, when Sharon Farrell recounted her affair with Bruce Lee to me, she didn’t have any contemporaneous documentation, but she described Bruce Lee with such specific details that I realized either she knew him intimately or she had read every single book ever written about him, like I had, because her account tracked perfectly.

Third, the more often a person has been interviewed the more likely they are to lie. Average folks don’t generally lie to journalists, and, when they do, they are usually bad at it, because they lack the practice. I found that the most unreliable sources were usually the people who had been interviewed the most about Bruce Lee, because they had their “stories” down cold.

Fourth, people will lie and tell the truth in the same interview. You shouldn’t throw out the entire interview just because you discovered one lie in it, but you have to be more careful about the rest of it. I interviewed one person who was a pathological liar but everyone else only lied when it was in their self-interest. When in doubt be most suspicious of self-serving tales.

Fifth, lying is an art form but so is lie detection. Cops are good at it because they spend a lot of time interviewing liars. The more people I interviewed the better my antennae got.

Sixth, the bigger concern for biographers, in contrast apparently to political scientists, is not with lies but with inaccurate memories. People are generally pretty good at remembering emotional moments—an argument or a fight or a sexual encounter—but they are terrible about time. There are at least a dozen people who claim they talked to or met with Bruce Lee on the day before he died. That’s because they talked or met with Bruce in the weeks or months before he died, and the shock of his death condensed the time frame in their minds.

Finally, the single most important thing for a biographer to reconstruct is the person’s timeline. I repeatedly had to go back and rewrite sections because I figured out someone had told me a true story but got the year wrong. As I argued above, chronology matters.

KFT: You must have read a lot of what has been written about Bruce Lee over the years in your research for this book. Did you notice any patterns in what he meant to his fans or admirers? Has the social meaning of Bruce Lee as an icon or image changed over time? As you talk to readers of your book, what role does he occupy in the social imagination today?

Matthew Polly: I didn’t focus a lot of my attention on fans’ reactions to Bruce Lee, but my general impression is that Bruce Lee as an international icon has meant different things to different groups. To white Westerners like myself he was the Patron Saint of Kung Fu. He was the reason we started studying the martial arts. Martial arts improved our lives, so we view him as an inspirational, missionary figure.

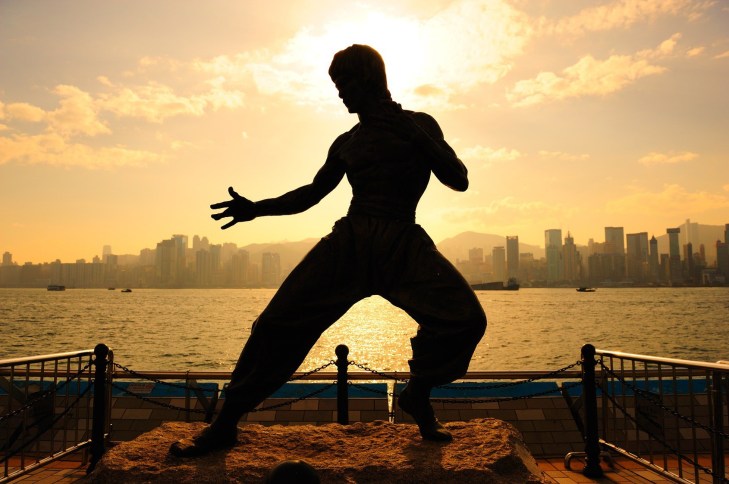

To Asian-Americans, he gave them their first badass archetype, so he became like the demigod of war. (Over time, as Bruce has remained the only iconic Asian-American, and no one else has been elevated to join him in the pantheon, the image of the Chinese kung fu master has begun to be seen as more of a burden or an annoying cliché.) African-Americans saw him as a non-white guy beating up white people in his films, so he was adopted by the hip hop community as a racial empowerment figure. In Eastern Europe he became a figure of anti-communist resistance. The first statue ever erected to Bruce Lee is in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

The scandals surrounding Bruce’s death soured the Chinese public on him in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the rest of SE Asia. I have a Taiwanese friend who told me when he was growing up Bruce Lee was dismissed for not being Chinese enough. His reputation didn’t turn around until the mid-2000s. Why? Mainland China had no idea who Bruce Lee was until they started to open up in the 1990s. The government decided to reclaim Bruce, like they did Confucius, as a Chinese hero. In 2008, state run TV (CCTV) did a 50-part, highly fictionalized, series about his life, which became the biggest TV hit in the country’s history. Suddenly Hong Kong became very interested in revitalizing Bruce’s image as mainland tourists flooded down to get their picture taken next to his statue in Hong Kong harbor.

My real expertise is in how Bruce Lee has been portrayed in the media—magazines, books, TV, and film. He is a fascinating figure because no one outside of SE Asia knew who he was. Enter the Dragon was released a month after his death, so his fame was almost entirely posthumous. At first there was a rush to simply explain who he was. The first two biographies about him were very thin but they contained the best reporting of all of them up until Russo’s and mine. Alex Ben Block wrote the first one in 1974 and it sold 4 million copies. His take was about like mine: Bruce was an actor who became a great martial artist. He was a bit cocky, egotistical, and self-centered but he was also a loyal friend and progressive figure on race.

What you can see is Bruce’s legend grows over time from these fairly accurate biographical studies until he became almost superhuman. Driven by the marital arts magazines, he goes from being a great martial artist to an invincible fighter, from a young man with a serious interest in philosophy to an enlightened Zen master. This culminates with the 1993 release of Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story, which adds perfect husband and father to the image. Then John Little released a series of books culled from Bruce’s extensive archives of letters and notebooks, which contained all those misattributed quotes we discussed earlier. By the late 1990s, he borders on a semi-religious figure, St. Bruce.

This causes a reaction and skeptics like George Tan, Davis Miller and Tom Bleecker seek to tear down this impossibly inflated image. Message boards on the internet are set up to debate “How Good a Fighter Was Bruce Really?” “How Did He Die?” “Where Is the Lost Footage to Game of Death?” And then it goes relatively quiet for about a decade. My goal was to avoid these fights over Bruce’s legend as much as possible and get back to what the first biographers were trying to figure out: Who was Bruce Lee really as a human being? I came to a similar conclusion only with a much longer bibliography.

KFT: My final question is about Matthew Polly. And I am going to cheat a bit by giving it two parts. You dedicated a lot of time to this project over a number of years. How has studying the life of Bruce Lee changed you as a martial artist or writer? And as one of the most reliable and popular authors to write on the martial arts, what sorts of projects are on the horizon? What should your readers be waiting for?

I’m much more interested in other people’s stories than I am in my own. That may also be a function of age. When I was younger I wanted to sort out what was going on inside my head, but I had an absolute blast figuring out what made Bruce tick. As for now, I haven’t decided if I’m going to write another book about the martial arts or a martial artist or perhaps a biography of a famous person in a totally different field. One of the main reasons people think of Bruce Lee primarily as a martial artist is because he died before he could branch out into different genres besides chopsocky. I’m convinced he would have tried his hand at comedies, thrillers, rom-coms, and dramas. If I were to die tomorrow, my short Wikipedia page would list me as a martial arts author. If not the next book then the one after, I’d like to branch out as well.

KFT: Thanks for dropping by and giving us another glimpse into Bruce Lee’s life and the process of writing about the martial arts. I am sure that I speak for all of the readers when I say that I hope you have at least one more martial arts volume left in you. But in any case, we hope to have you back on Kung Fu Tea soon. Seriously, I can think of half a dozen topics that we need to chat about!

oOo

If you enjoyed this interview you might also want to read: Bruce Lee: Memory, Philosophy and the Tao of Gung Fu

oOo

July 9, 2018 at 9:03 pm

Just in answer to one question about how well Bruce Lee could fight, my Hong Kong connection back in the day, who was the best martial artist I ever saw in person, said Lee was extremely skilled and, if not admired, at least respected as a very high level martial artist. People who have ever trained in martial arts know it takes a very obsessive person with great talent to excel at the highest level because the rewards for such dedication are not commensurate with the time and energy spent.

December 8, 2018 at 1:22 pm

I would argue that Linda Lee has been trying to sell a lie since 1976. Whatever you want to think about the outcome of their fight, Wong Jack Man didn’t lose. Despite whatever David Chin is saying these days, back in 2006 he said, “To me, you can say it went both ways…” It still seems absolutely ridiculous to me that Lee would quite Wing Chun because he didn’t win fast enough. He’s the only martial artist I’ve ever heard of quite his style for that reason.

February 20, 2019 at 5:04 pm

Matthew Polly’s book “Bruce Lee, A Life” is chock-full of errors, hearsay, and biases, thus far no book review nor interview, including this one by Kung Fu Tea (KFT), has called him out. To be fair though, KFT did provide Polly ample chances to demonstrate he was an expert in Bruce Lee, in martial art, in Hong Kong and Chinese culture, and in biography writing in general. However, Polly’s knowledge in all these areas seemed to be very limited, and he was quite evasive in answering some of the more difficult questions posted by KFT.

The following is a LONG and detailed review of this KFT interview (and a partial review of Polly’s book).

Title of this KFT post is “Matthew Polly on Bruce Lee and The Art of Writing a Life”, of which the word “Art” should have been double-underlined and in bold font. Polly’s book is definitely a work of art/fiction, because the level of inaccuracy and bias can hardly qualify it an objective biography. Barely into the book’s Prologue and the first 2 chapters, more than 50 factual errors have been spotted. It would be pointless to keep counting after that, as this level of inaccuracy persisted throughout the rest of the book

Polly has already given a number of interviews to promote his book, and none thus far has challenged him on the issue of inaccuracy. When KFT asked him to advise “graduate students” in research methodology, Polly could have said “accuracy and truthfulness”, but he did not.

There are a number of book reviews praising Polly’s to be the “definitive” Lee biography, one wonders if those reviewers actually read the entire book, or know the subject well enough to give such high compliment. Compared to the 2 books by Linda Cadwell (Lee’s widow, in 1975 and 1989), or those written by Lee’s other family members or close friends, Polly’s certainly covered many areas that they left out, such as Lee’s death and his womanizing, but Polly also left out several key areas.

For example, a 2017 Chinese biography of Lee (released one year prior to Polly’s) contains two full chapters on what happened during the 40+ years after Lee’s death – the public reaction in Hong Kong (HK) and USA, Bruceploitation of all sorts, infighting between the various factions of Lee’s family, the zeal in legendizing and canonizing Lee in recent years, etc. Polly’s book only gave a passing mention of this part of Lee’s equally fascinating story. To examine Lee as a cultural phenomenon, this part of his story is indispensable.

Notwithstanding the much-hyped cheerleading, there are actually a few objective and even slightly negative reviews of Polly’s book. “Enter the Door Stopper” quip by Dublin-based Irish Times is quite fitting. While KFT seemed to agree with Polly’s new theory that Lee died of a heatstroke, South China Morning Post (a HK English newspaper) has already called such theory bizarre. There are at least 5 problems with Polly’s heatstroke hypothesis:

(1) Lee died indoors, not outdoors;

(2) located in an affluent neighborhood, Betty Ting’s apartment (Lee’s deathbed) had air-conditioning (there are photos showing the bedroom with AC units);

(3) Lee grew up in HK and should know how to deal with such “unusual scorching” (Polly’s words) summer heat;

(4) the two doctors in HK (Dr. Langford, Lee’s family physician, and Dr. Wu, a well respected brain specialist) whom had treated Lee, had never even mentioned heatstroke as a possible cause;

(5) Polly does not know much about HK (he lived there only a few months), and he has zero medical training.

Having been born and raised in HK myself, and I was in the city on that summer day in 1973, I found nothing unusual or particularly dangerous about such heat (and even with a 95%+ humidity). In his book, Polly suggested there were a few cases involving American football players in which heatstroke was a possible cause of death. As an avid CFL and NFL fan, I can tell you that heatstroke has never been a concern with both football leagues. And, the type of physical activities Lee engaged in Ting’s apartment that fateful day was nowhere near to those of American football.

Polly continued on to say that Lee’s death is controversial – because he died young at the peak of his career. Really? Dying young is tragic and sad indeed, but not necessarily controversial. The controversy was about where and how he died, and how some key people lied about it. Lee died on the bed of his mistress Betty Ting, while his wife and brother, and two of the three eyewitnesses (including Ting) whom were physically with Lee shortly before he died, lied about it, at least initially. As such, testimonies given by some of these people at a later HK government inquiry were suspect.

To this day, there are still unanswered questions about the root cause of, and the actual sequence of events leading up to, Lee’s final breath. With the passing of Dr. Eugene Chu in 2015, and Raymond Chow in recent weeks, Ting is the only eyewitness left, whereas her documented versions thus far are still full of holes. Both Chow and Dr. Chu had been masterfully evasive all these years when asked, and they carried whatever secrets to their graves. There could be stuffs in the HK police files capable of shedding additional lights, but they are yet to be released to the public.

For Chinese culture at the time (1970s), Hongkongers viewed extramarital affairs extremely negative (not polygamy though, because it was legal in the pre-colonial time carried forward, and normally done in the open), especially when someone claimed to be such a perfect husband, and then had an affair with someone like Ting. For many, she is still a questionable character, not so much about her being typecast as a villain in movies, but more so about who she was when she first hooked up with Lee, and what she did after Lee’s death.

In recent years, Ting appears to be on a mission to repair her well deserved beat-up reputation, and cashing in whatever residual fame she still has, while Polly thought he hit the jackpot by having an “exclusive” interview with her. Likely unbeknown to poor Polly, Ting had already given a number of broadcast interviews with the Chinese media since 1975, and more so in recent years since 2013, whereas Polly’s book has absolutely nothing new to add. If Polly has any idea about HK, he should have known all that, and also the fact that most Hongkongers still do not buy her highly self-serving stories.

Regarding Chinese martial arts (CMA) in general, Polly offered his “expert” wisdom in this KFT interview that there are 4 categories (he called subsets). But, he should have added one more – 5) the pretentious commercialization of CMA, such as the ‘Shaolin Inc.’ in China and all over the world.

Polly often boasts about (and indeed, he had written a book about it) his 2 years stint at a certain Shaolin diploma mill in China. He said the monthly fee was US$ 1,300, and for a 2-year program, that would cost him roughly US$ 31,200. In 1990s money, that’s the down payment for a decent house in his hometown Topeka, Kansas!

Such short course would have zero chance to make its attendee expert in anything, even if it is at all legitimate and indeed at the “real” Shaolin Temple. Compared to my experience in learning CMA in HK in the 1960s and 70s, the first two years were barely enough to cover the basics. With Polly’s limited Chinese language skill, I doubt very much that he was able to realize he’d been had.

The claim that Shaolin Temple invented CMA (by many of the Shaolin proponents) is utterly absurd. Shaolin Temple was/is a temple, a Buddhist temple. Its intended purpose of existence was/is for religious enlightenment (and indeed, it was the birthplace of China’s Chan/Zen Buddhism branch), whereas CMA was only a tiny part of the temple’s actual history (briefly at the onset of the Tang Dynasty).

Shaolin Temple’s status in CMA was largely a work of fiction based mostly on stories and myths accumulated in novels, operas, and storytelling (shuo-shu or ping-hua) throughout the long history of China. To gain an air of mythology and legitimacy, a number of CMA schools (e.g. Wing Chun) had invented their own Shaolin lineage.

Polly seemed to suggest that Ting appreciated his Shaolin experience in terms of Buddhism, as he could better connect with her with it. During his interview with Ting, she claimed she is now “deeply into Buddhism”, sort of a born-again, and she “brought up repeatedly” (admiringly) that Polly was lucky enough to “had lived in a Buddhist Temple in China”. Ting has been selling her ‘born-again’ story to the Chinese public for years, but with very few takers.

Did Polly now try to sell his Shaolin stint a true monastic Buddhism experience? Unbelievable! Maybe Polly’s Shaolin credentials is good enough for himself, for his cheerleaders, and for people like Ting, but in reality, most Chinese circles in HK, Taiwan, PRC, or overseas just consider it one big joke!

Polly openly admitted he was only an amateur MMA fighter and never fought in a professional bout. The term “amateur MMA fighter” is an oxymoron. If one never fought in a sanctioned professional bout, then he is just a pretender, not a fighter, and definitely not deserving the MMA label. The “Polly fight” on Youtube (2009) may be entertaining, but just like his “American Shaolin” claim – it’s as real as David Carradine’s role in the 1970s “Kung Fu” TV series. Both are pure fiction.

Without a doubt, Simon & Schuster is a reputable publisher and it’s fair for Polly to brag about getting his book published by it. However, did he just trash his two earlier books in this interview? Because they were published by some small boutique publishers (now imprints of Penguin) not of the same caliber as S&S. Anyway, S&S publishes a lot of books every year, and their company logo is no guarantee in quality (evident in the level of delinquency in Polly’s book). Of course, as a major publisher, S&S knows how to promote, and it’s no surprise that there are so many good “reviews” out there.

Regarding Lee’s “achievement” in philosophy, I am onside with Albert Goldman’s “fortune-cookie philosophy” quip (in a 1983 Penthouse magazine article) – Lee was full of empty sound bites, with very little substance. I think “chop suey philosopher” may be even more appropriate. Besides Lee’s harmless white lie claiming he majored in philosophy at the University of Washington (actually in drama, never graduated), most of Lee’s famous sage-like utterances were actually “appropriated” from someone else. Polly was evasive in addressing this plagiarism issue when asked by KFT, and admitted he just “let it slide” in his book.

Not only did Lee never give due credit to the originators, he also misquoted (or misuse) some of those catchphrases. For example, “be like water” (actually by G. Koizumi, in the forward of a 1952 Judo book) which Lee followed up with “if water goes into a cup, it becomes the cup, if it goes into a teapot, it becomes the teapot”. We Chinese call this ‘drawing a snake, but adding legs’.

Here, Lee tried to impress his flocks about water’s formless character, but he actually said the opposite. If water can be shaped by a cup or teapot (Kung Fu Teapot perhaps? ha-ha), then water is not formless. What Lee should have said is that water is extremely malleable, and can change to whatever form it encounters – not formless! This indeed is a perfect example of Lee’s half-cooked ideas. I truly feel if he had more time to fiddle with, he might have figured it out and said it differently.

Also, this water adaptability is nothing new. It has been a basic tenet of Tai Chi Fist since the Late Qing Dynasty (also in Daoist philosophy as well). And, it has an even older source – by Sun Zi in his famous “Art of War” book (Chapter 6), circa Confucius time. If Lee really understood the Chinese philosophy books he kept in his impressive book collection, then he should know he was quoting Sun Zi, whereas quoting such famous luminary without giving proper acknowledgement was unwise.

Polly vaguely conjured up two possible defence for Lee’s plagiarism – first, Lee was a “young man” and he did not know any better, and second, the notebook escape clause. But, Lee was already 30 something at the time, and should be mature enough to articulate his great ideas in writing. He did have ample opportunities to do so – with his many Black Belt magazine articles, the last one in 1971 (age 30), and to a lesser degree, his only published book of 1963 (at age 23).

As for the notebook escape clause, one should know that Lee’s now-famous personal notebook (or notebooks, plural, containing most of his so-called wisdom) were really no more than the unedited personal notes, scribbles, and doodles he kept since his high school days. They were things he read or heard, unfiltered, and then copied down (before the advent of personal photocopiers or scanners), or just raw ideas in his head. It’s debatable how much of them were his mature thoughts.

It’s well documented that Lee did not want his notes to be published at all, or at the least, not in a way he had zero control of, or before he had a chance to polish them. After Lee’s death, Linda and her handpicked writers and book editors shamelessly churned out bestsellers using those notes, with their hugely debatable interpretation, but fraudulently claiming Lee was the actual writer. Initially, those books did not provide proper citation of the reference materials and hence the plagiarism charges. And only until recently that such mistakes were rectified somewhat, in some of the updated editions.

Nonetheless, Lee still can’t escape responsibility, as it is absolutely true when he uttered those famous phrases in public, he never once said “oh, by the way, I did not invent this, this is from…” – not a single documented occurrence! Neither Polly’s book nor this KFT post pointed this out.

Regarding biography writing in general, Polly argued that all biographies are somewhat imperfect and contain some “elements of fiction”, it’s just a matter of degrees. Really? Fiction in biography? There is a BIG difference between fiction and logical argument/opinion.

For me, this high degree of defects and fiction in Polly’s book is a deal-breaker. It’s absolutely astounding as if S&S’s editors did not do any fact-check at all. Polly also disclosed in this interview that John Little did some editing for him, but Little is hardly an impartial fact-checker, as he was once a favorite in Linda’s inner circle, and published many Bruceploitation books on her behalf.

KFT did make a point about Polly’s prior books – which were written in a first-person point of view – while this biography, by nature, would require a much higher degree of objectivity, and a lot more research. This may be the primary reason that Polly failed so miserably, as if he wrote this Lee biography still on a first-person basis (though Polly insisted that he tried very hard to edit himself out of the book). It’s funny that Polly often passionately referred to Lee on a first name basis, as if he, only a toddler back then, knew Lee personally.

Polly is wrong in his frequent claim that there is not enough Lee’s biographies out there – he said only “over a dozen” in this interview. In other interviews, he claimed even less, and he thought there was a total void in the past 25 years, and stated that such deficiency was the primary motivation for him to write his own Lee biography. In reality though, 200 or so books have already been published about Lee, half in English, half in Chinese, and about 1/3 as biographies, many of which in the past 25 years!

Granted, many of the existing biographies are far from perfect (most of those from Mainland China were absolutely appalling), but collectively they should still provide a base, a good database. Possibly, Polly never read any of the Chinese references (due to his limited Chinese language skill), including the Chinese book mentioned above (published by one of the most reputable publishers in HK) which is more comprehensive and accurate than Polly’s book.

I strongly disagree with Polly’s backhanded criticism against Charles Russo and Rick Wing in this KFT interview. Polly said this: “… the type of person who prefers to tell his story to a non-expert is usually a con artist. Honest people prefer an expert…”. I have read the books Polly referred to, and I don’t think these authors are con artists. Wing actually did a good job to be neutral in spite of his status as Wong Jack Man’s pupil/heir.

Polly proceeded to fire off some derogatory remarks towards Wing and Wong Jack Man. This just shows Polly’s hypocrisy about being neutral and fair as an impartial biographer. Though Polly did not admit he was a fanboy of Lee, his bias is prevalent throughout his book (indeed, a 2013 article of South China Morning Post suggested that Polly truly idolized Lee).

As a skilled manipulator, Polly cleverly revealed some of those obvious shortcomings of Lee (loudmouth and womanizing, for example) and hoped the readers would buy the rest of his arguments (for example, Wong Jack Man lost the fight, or Lee died of heatstroke). As far as I know, both Russo and Wing have serious reservation about Polly’s book, and I would recommend theirs over Polly’s anytime.

Polly was correct though to conclude that Lee was an actor first, martial artist second (already pointed out by many, including the Chinese book mentioned above). But, he missed the bigger picture about Hollywood. There are thousands of wide-eyed dreamers flocked to it every month, and they are of all shades of skin colours, from all corners of the Americas, and the world, and with all kinds of “funny” accents. Competition is/was fierce, and blaming racism for everything is too simplistic, and too condescending for a Chinese Canadian like me.

One only needs to objectively looks at most of the success stories of Lee’s era – McQueen, Colborn, Eastwood, Bronson, Elke Sommer, or older stars like Wayne, Yul Brynner and Ingrid Bergman – they all went though their trials and tribulations, paying their dues along the way. Were many of them treated unfairly one time or another? Sure they were, but that’s the reality of movie business anywhere – movie studios must cater to the taste and liking of their paid customers.

Chinese American population in the US has always been less than 3% (currently at about 1.1%), and movie scripts featuring Chinese heroic leads are few and far between. But of course, there was abject racism, which was vividly demonstrated in the shameful and dreadful anti-Chinese legislation in both USA and Canada from 1880s to 1950s. Indeed, racial stereotyping was still common during my own time in Canada. We can only control but never totally eradicate racism, as also vividly demonstrated by the Alt-right movement currently active in the US and Europe.

So, for any Chinese/Asian to embark on a Hollywood career, now and then, it would be totally naïve to expect an easy ride. The same is true for any non-Chinese actor trying to make it big in HK or China. Lee was an accomplished child actor in HK before returning to the US, how could he not know that? Only pretentious do-gooders would try to use such condescending excuses for self-serving purposes.

Surprisingly, Polly said this: “… after the Green Hornet was cancelled and he (Lee) couldn’t get another paying gig …”, which is blatantly incorrect. The truth is, though without a big name agent, Lee continued to get decent paying jobs in Hollywood, often with the help of his Hollywood insider friends like Silliphant (a prolific producer, and an Oscar winning screenwriter).

Indeed, Lee got 3 to 4 career-advancing gigs per year on average throughout his remaining 3 years in Hollywood (after “Green Hornet”, and all the way to the much-praised “Longstreet”, while getting Warner Brothers interested in his “Silent Flute” project). That’s not too shabby for a greenhorn (pardon the pun), especially back then in the 1960s and 70s Hollywood.

KFT did express concerns about the large number of interviews Polly incorporated in his book, questioning if all such interviews were “reliable” and Polly’s ability in “assessing the credibility” of them. Polly was evasive about this too. Typically, references of many quotes are listed in the endnotes of his book, but there are still a lot of them without specific reference. Were they from questionable sources that Polly didn’t want to list them? Or, he just made them up?

Also, Polly just typically repeated the quotes or dialogues verbatim, and offered no further substantiation as to their truthfulness. That means many of the quoted dialogues in his book are no better than documented hearsay. Of course, they are effective page-fillers (verbatim quotes in virtually every single page) resulting in the impressive 656-page size, and hence, the “door-stopper” criticism. A responsible biographer would be more diligent in screening, and should not include anything that contains falsehood. Or, at the minimum, provides pertinent discussion about the validity of such quotes.

Polly’s take on Asian-American’s view of Lee is definitely wrong, as far as this Chinese Canadian is concerned. But he is free to express his opinion, and so do I. His take on African-American’s view is problematic, as it sounds more like racism. Polly spent very little time in HK, and as a result, his narrative about the place pertinent to Lee’s life was full of errors, and at times, pretentious.

As a wide-eyed Anglo-Saxon from the American Midwest seeking wisdom from the Oriental culture, I presume Polly’s intention was honorable, but his book “Bruce Lee, A Life” is really subpar, and in fact, quite misleading. His romanticism with CMA and Lee is forgivable, and I hate to be the one to tell him that there may be no bluebird over the Kansan rainbow, and dreams may never come true. I hope his next non-fiction project will improve, at least on the accuracy front.