Captain America Thwarted

I spotted a flash of red, white and blue as I looked up from the electronic display mounted on the top of the treadmill. It was telling me a depressing story of miles left to go. But the sudden burst of excited kinetic energy suggested that things were about to get interesting.

Having a somewhat flexible schedule I try to go to my local YMCA during the late morning, after the initial rush of pre-dawn workouts and fitness classes have died down. At 10:00 you do not have to wait for machines to open up and, if I am lucky, I can usually find an empty studio in which to practice my various forms.

Still, the Y is never empty. There are a number of fitness classes for senior citizens, and it offers daycare options for local families. It is not uncommon to see large groups of children being shuttled from one activity to the next.

For reasons unknown to me, it had been decided that on this particular day the kids in daycare would be exploring possible future careers as masked crime fighters. All of the children loitering in the front hall were in surprisingly elaborate costumes. Batman and Superman were both present, and I secretly wondered if the old tensions between these two heroes would bubble to the surface. Luckily all was calm.

I noted with approval a group of kids dressed as Ninja Turtles. Unfortunately whoever supplied the costumes had forgotten the nunchucks, swords and other weapons that really impart a sense of individuality to each turtle. No parent is perfect. One little boy dressed as Spiderman stood outside of the group looking slightly awkward, totally capturing the essence of Peter Parker. I did not think about this band of vertically challenged vigilantes again after they were corralled (with considerable effort) by an entire team of caretakers and marched off to whatever godforsaken place needed that much crime fighting.

It was about an hour later that I spotted the red, white and blue comet streaking along the raised indoor track that looked down on the gym, weight and cardio rooms below. It would seem that the “day had been saved,” and a four year old female Captain America was burning off some extra excitement by running and leaping on the track, her long blonde hair streaming behind her.

A number of the middle aged female walkers on the track complimented her on how “cute” she was. But then there was a sudden shift in the atmosphere.

Whatever imaginary battle Captain America was engaged in had become heated, and she started to punch at her imaginary opponent, hitting nothing but the empty air. Almost immediately our diminutive hero was surrounded by no fewer than four walkers (all unrelated to her), each chastising her in turn that “We do not hit things. Punching is bad!” The look of defeat that crossed her face was crushing. Play, it seems, must always be regulated.

Losing the Heroines of Old

Modern students of the Chinese martial arts have been fortunate to inherit a rich body of art, literature and folklore surrounding their practice. Much of this dates back to the Republic of China period when, between the 1920s and 1930s, these hand combat systems surged in popularity, both in the training hall and in the realm of popular culture. Novels, newspapers and radio programs all told the stories of popular martial arts heroes, and a surprising number of these heroes were, in fact, heroines.

Most western students of Wing Chun are familiar with the stories of Yim Wing Chun and her master, the Buddhist nun Ng Moy. On a symbolic level these stories carry an important set of messages for those attempting to understand the nature of this fighting system. More recently both of these protagonists have come to function as proto-feminist symbols for many kung fu students.

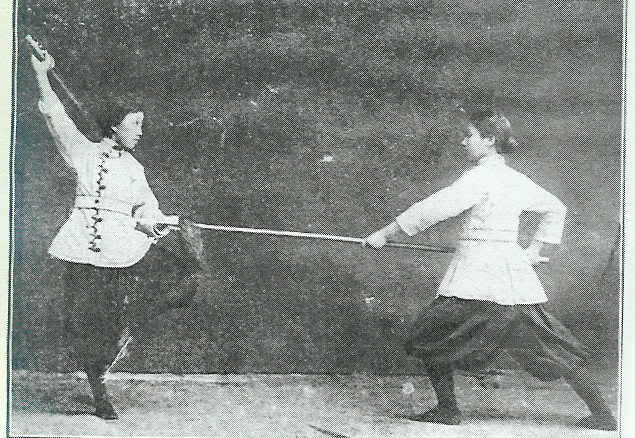

These two women enjoy a great deal of company. The period’s literary record is full of stories of female martial artists, duelist and adventurers. Strictly speaking this is not an entirely new development. Some of the earliest detailed literary discussions of swordsmanship in China mention female practitioners, and the motif would go on to enjoy renewed popularity later in the 20th century. But there is something interesting about the sudden explosion of martial heroines at that particular moment in Chinese history.

One might assume that this simply reflected the fruits of China’s budding social reform movements and the sudden appearance of larger numbers of female martial artists. In reality the situation was actually more complicated than that. It is true that some groups, like the Jinwu Association, worked hard to promote the teaching of the martial arts to women. And a number of folk teachers (including no less a figure than Wong Fei Hung), opened classes for women.

Yet these gains were limited in nature. A strongly felt taboo against male-female physical contact ensured that there was little (if any) mixed sex training. And many of the gains won by the women of Jingwu were lost by a subsequent generation as the Central Guoshu Institute took a much more statist and patriarchal approach to the production of the ideal Chinese martial hero (see Morris, 2004). As Henning and others have pointed out, the stories of the era remained, for the most part, just that.

The important thing to realize is that this sudden visibility in popular culture did not result in a radical transformation of who sought martial arts training. A number of expectations, identities and traditions, some very visible, others less so, conspired to ensure that women would remain underrepresented within the actual practice of the Chinese martial arts during the pre-WWII era.

It was not so much that women in the 1930s were barred from studying the martial arts. Rather, many other things were expected from them. Competing demands, clashing identities and social expectations can form a very high barrier to entry.

Many of these forces came to the fore in 1934 when it was revealed that the Central Gusohu and Physical Education Academy was plagued with cases of sexual harassment. Morris reports that the Director, Zhang Zhijiang, decided to solve the problem of “immoral relations” by immediately banning female students from the school.

In a newspaper column Ms. Qiu Shan blasted this solution and noted that women were once again being sent “back into the kitchens” when it was probably the men who should be punished. Yet it was Tain Zhenfeng (the editor of a competing martial arts journal and persistent critical of the Central Gusohu Academy) who summed up the national mood when he noted, in a matter of fact tone, that a woman’s place was in the kitchen. After all, what upstanding (male) Chinese martial arts hero would want a dinner prepared by a “dirty cook” rather than his own wife? (Morris, 210)

We tend to think of history as having a distinct arc. Events are imagined as only flowing in one, progressive, direction. Yet the starts and reversals of the Republic era social reform movements demonstrate, in no uncertain terms, that backsliding is possible. Social progress is not inevitable. When it was decided that other factors were more important (such as the plan of many Gusohu intellectuals to save the Chinese nation by making it more “masculine”), the gains of a previous generation were lost. Nothing in is automatic.

A View from the Mats

Kreia, a fellow student at the Central Lightsaber Academy, had agreed to be interviewed as part of my ongoing fieldwork. I was particularly interested in her thoughts as she is also a longtime Wing Chun student of Darth Nihilus. While I study with the lightsaber group I have only occasionally had a chance to observe his kung fu classes. Needless to say, I was interested in her thoughts on the similarities and differences between the two.

As we got into the interview I realized that Kreia had more of a history with the martial arts than I realized. I began to probe a little deeper to get a sense of what she had practiced, and what her experiences had been like. Gender was not a focus of our interview, but it came up in a number of interesting ways.

The Central Martial Arts Academy, which houses the CLA, is a highly diverse organization. This is reflected in the racial and ethnic backgrounds of both the instructors and many of the students. If you were to walk into the middle of a typical training session you would find two different classes being taught at the same time. Within them you would see a mix of African American, Hispanic, Asian and Caucasian students. The school attracts students who are both teenagers as well as those in their 40s and 50s. And while women are a minority of the student body, they are well represented.

As you break things down a bit further and look at individual classes, some interesting patterns begin to appear. Kali appears to be a little more racially diverse than Wing Chun. Jeet Kune Do does a little better on the gender front than Kali. And Wing Chun seems to be attracting a slightly older group of students. One of the most notable things about the lightsaber class is the number of family relationships it seems to accommodate. In the class we have multiple sets of couples, adult siblings, parents and children, all working together with a surprising degree of harmony. I have actually never seen anything quite like it.

After collecting data for a longer period of time I will need to sit down and try to make statistical sense of it. But in the mean time I asked Kreia for her thoughts. What was it like to train at this school as a woman? Did she feel any differences between the lightsaber and the more traditional class?

Her answers were generally positive. She felt supported and respected by both the instructor and the other senior students. Her only complaints were more age related. Sometimes younger training partners might go at things a little harder than was good for her (injured) back and neck. But she did not suggest any sense of individuals “going easy on her,” or holding her to a different standard because of her gender.

After answering my question she became uncharacteristically reflective for a second. “It wasn’t always that way” She noted. Kreia related that as a college student she had become interested in Judo and studied at a school on the campus. Apparently she approached her training with the same sense of grit and determination that she applies to pretty much all of her life projects. Yet she confessed, “I hated it.”

Kreia stopped herself. It wasn’t Judo that she hated. It was the class. It was her instructor.

When I asked why she responded with a story rather than an explanation. She related a time when she put a larger male student in a choke hold. She noted that he was not making any effective movement towards escaping, yet he was also refusing to tap-out. She warned him to tap out two separate times, but the male student simply refused to concede defeat at the hands of a more experienced female who (following the school’s own protocols) maintained her position.

Of course the male student passed out briefly and then recovered. Rather than lecturing him for refusing to respect his training partner (or even the basic laws of physics and biology), the class instructor chose to discipline Kreia, even though she had done everything that was expected of her. Some students, it seemed, were more equal than others. It would be many years before she resumed her martial arts training, with a very different instructor in a different style.

Our Hero Earns her Gloves

By this point James and I were pretty good friends. He worked as a personal trainer at the YMCA. I knew him better as a kickboxing instructor and talented amateur fighter. At the time he and I were training together, and he was helping to introduce me to the local kickboxing scene.

Being one of the trainers on duty it was James’ responsibility to make sure that everything was running smoothly in the fitness area. As the mantra “We don’t punch!” rang out, he sprang into action.

When not fighting for the fate of the free world, Captain America was the daughter of one of James’ female students. She took her kickboxing training seriously and was trying to decide whether she wanted to take the “next step” and line up an amateur fight at one of the big events that were held every couple of months in the city. James had been keeping an eye on the daughter (released early from the daycare activity) as her mom finished up a fitness class in another section of the Y.

Walking over to where the gaggle had surrounded the little girl he asked (only half rhetorically) “Are you trying to stifle her creativity?” Of course they were. That was the point of the entire exercise.

He then took the girl back downstairs to where there was some open floor space by the trainers’ office. Quickly ducking into the room he came back with a set of wrist wraps and boxing gloves.

James proceeded to inform the little girl that Captain America was a pretty serious boxer. As such she would have to learn how to wrap her wrists. The little girl looked on with a sense of awe as he wrapped first one hand, wrist and forearm, then the other. Next he placed the comically large boxing gloves on her hands. By this point Captain America was basically trembling with excitement. The group of walkers on the elevated indoor track looked down at the unfolding scene with visible discomfort.

Lastly James produced one of the “weeble-wooble” toys that children are occasionally given to hit from a closet. I had no idea the YMCA even owned one. He then gave the fully geared up superhero some quick pointers on her jab and cross and told her to go at it.

The first few punches were tentative, but once it became clear that no one was going to stop her, “our hero” let loose a barrage of flying fists. It was an imaginary beat down for the ages. The walkers looked on at this unabashed display of a little girl “hitting” and “punching” in abject horror.

At this point the Captain America’s mom, water bottle in hand walked up. “My gosh, did James actually get you some boxing gloves? That’s my girl! Just like her mom…” Our hero beamed in victory.

Conclusion

Kreia’s interview was very productive and I thought quite a bit about it as I drove home. Obviously I will never understand exactly what it means to be a female martial artist. I have not personally experienced how attitudes in training halls have evolved over the last couple of decades. Nor can I do more than empathize with what must have been the crushing experience of China’s Republic era female martial artists upon seeing their hard won gains being rolled back in the 1930s.

Gender issues have never been the primary focus of my research. Nor, on a more personal level, are these my stories to tell.

Yet I am acutely aware of the debt that I owe the Kung Fu Sisters whom I have had the privilege of working with over the years. They have been some of the hardest working and most skilled martial artists I have met.

It is easy to say that we want to support female martial artists in our training spaces. And the social sciences offer us some very helpful guidelines on how we can create welcoming spaces where everyone has a chance to succeed. Everyone benefits from seeing students like themselves reflected in a school’s art. Everyone also benefits from seeing someone like themselves succeed as a senior student, coach or instructor who is respected in their field. No one benefits from the maintenance of verbal (and non-verbal) double standards that treat the abilities and accomplishments of female martial artists as less than their male peers.

Yet, as much as we may sometimes wish it were the case, the martial arts do not exist as a separate sphere, held in pristine isolation from the rest of society. These things are first and foremost social institutions, which mean that they reflect the norms and attitudes of the communities that produce them.

This suggests that if you want to support the inclusion of female martial artists in your training hall, you are going to have to support them, and other women like them, in a lot of other places first. Simply put, you will never have the chance to train with the women who have already internalized the message that “good girls” do not punch, kick or choke. Those are messages designed to stifle Captain America’s creativity.

oOo

If you enjoyed this essay you might also want to read: Producing “Healthy Citizens”: Social Capital, Rancière and Ladies-Only Kickboxing

oOo

2 Pingback