Introduction

Gu Ruzhang is one of the best known martial artists of the Republic of China era. He is remembered today as a pioneer who helped to bring Northern Shaolin to Southern China. Most accounts of his illustrious career start with his appearance at the first National Guoshu Exam held in 1928. At the conclusion of this tournament he was awarded the title of “guoshi” (national warrior) and came to the attention of important military leaders in the Nationalist Party (GMD). They would subsequently sponsor his teaching mission to the South.

Unfortunately these accounts omit some of the most interesting aspects of Gu Ruzhang’s life and career. Perhaps the real question that we should be asking is what unique set of circumstances led him to Nanjing in the fall of 1928 in the first place? We have already seen that a close examination of the careers of other martial artists can expand our understanding of both civil society and martial culture. My own personal background is not in Northern Shaolin, nor am I really qualified to speak to the specific substance of Gu Ruzhang’s martial method or training system. However, a brief outline of his career does open a valuable window onto the rapidly evolving realm of the civilian fighting systems in the Republic of China period.

Much of my own research focuses on the evolution and development of Southern China’s martial culture in the 19th and 20th century. Gu Ruzhang is a central figure in many of these discussions precisely because he crossed cultural boundaries and helped to promote and popularize different approaches to the Chinese martial arts. For those reasons alone his career might make an interesting case study.

Still, none of us are free to make our lives exactly as we wish. Gu Ruzhang’s career was both constrained and enabled by powerful forces within Chinese society. Some of these were the direct result of the political turmoil that China experienced in the first half of the 20th century. Others were a side-effect of the rapid modernization and urbanization of the state’s traditional economy.

Gu Ruzhang’s story is as much about political history as it is anything else. By exploring these sometimes neglected aspects of his life and career I hope to shed a light on the basic forces that were shaping the development of the traditional Chinese martial arts more generally. His career coincided with a period of immense change in the way the traditional fighting styles were imagined and taught. I hope that a brief discussion may help to clarify why these changes began to emerge when they did.

Gu Ruzhang: Creating a Tiger

Gu Ruzhang’s life has become the subject of many legends and stories. Some of them are basically true, others are vast exaggerations. Nor did he leave a body of literature behind as did some of his contemporaries. All of this makes documenting his life somewhat challenging. The following account will try to stick to the “known facts” while placing them within the proper historical context.

Gu Ruzhang (“Ku Yu Cheung” in Cantonese) was born in 1894 in Jiangsu province in Funing County. It doesn’t appear that his family was rich, but his father did run a successful armed escort company which employed a number of local martial artists. These sorts of businesses thrived and prospered at the end of the Qing dynasty. As the government’s grip on society weakened it became increasingly dangerous for either people or goods to travel on the roads.

Local highway men were a constant concern. One of the most common solutions that merchants employed was to hire specialized armed escort companies to accompany their caravans. In fact, by the final decades of the Qing dynasty such firms had become one of the leading employers of martial artists.

Gu’s father is said to have been an expert in Tan Tui (springing legs) as well as the art of throwing blades. These skills were an important part of his professional reputation, though of course by this point in time most bandits (and the armed escorts that dealt with them) also carried modern and effective firearms.

Like many martial artists of the time, Gu’s father was basically illiterate. This did not make running a business any easier and he appears to have wanted to provide his children with the benefits of at least a basic education. In 1901 Gu was sent to complete a year of primary schooling. It should be noted that Gu was the second son (he had one older brother and a younger sister), so we can probably assume that his schooling was less extensive than what his older brother might have received.

In 1906 his education changed from the literary to the strictly practical. From the age of 11 Gu was instructed by his father. He was first introduced to the form Shi Lu Tan Tui. Unfortunately this course of study was also fated to be short lived. Within two years his father was struck with a lingering illness that left him confined to his bed.

What happened next is a little unclear, but it appears that he advised his children on their future educations shortly before he died. Gu reports that his father recommended that he seek out Yan Jiwen (a former college who had also been a player in the local escort industry) in Shandong to continue his martial training.

However the youth did not set off all at once. Instead he stayed with his mother for an additional two years. This was probably in observance of the traditional mourning period. After that he left for Nanjing where he was enrolled in a middle school to continue his formal education.

Unfortunately that situation does not seem to have agreed with him. One year later (in 1911) he and a classmate (who was also a cousin) named Ba Qingxiang set out for Shandong to find “Great Spear Yan.” At the time Gu was likely 15-16 years old.

It is interesting to note the timing of this career change. The Qing dynasty was overthrown in 1911-1912. The nation was full of revolutionary sentiments and young men across the state felt a powerful “call to arms” in this period. The martial arts (which had suffered badly in the wake of the Boxer Uprising) also began to become more popular in this period. This was especially the case of anything that could claim to be tied to Shaolin or the secret societies that had resisted the now discredited Qing government.

Again, we don’t actually have any day to day accounts of what Gu was thinking or feeling. Yet I find it to be suggestive that it was at this specific moment that he decided to dedicate himself to the study of the martial arts.

Gu and Ba apparently had little trouble locating Yan Jiwen or convincing him to teach them. At the time he was actually running a small school and he seems to have been happy to take on the task of instructing the son of his friend and former colleague. Ru began his training by relearning his Tan Tui sets to his new teacher’s satisfaction. At that point he was introduced to the ten sets of Northern Shaolin, a variety of weapons forms, Iron Palm training and Small Golden Bell Qigong.

Gu stayed with his new teacher for quite some time. He studied in residence in Shandong for at least eleven years. In 1922 Gu received world of his mother’s death. Decorum mandated that he return to his home village and observe the proper period of mourning. At this point Yan proclaimed that Gu’s education was complete and he was ready to head out into the world.

The next two to three years were spent back in Jiangsu province. During this time Gu lived with his cousin Ba and worked to hone his skills. Yet once again his career plans changed.

Rather than opening a school or joining a military academy, Gu reappears in the historical record in 1925, employed as a clerk in the office of the Finance Minister in Guangdong Province. Many of the better known legend of Gu’s martial feats date to this period. For instance, this was when he supposedly killed a Russian War Horse with a single blow from his iron palm.

Of course the really interesting question is not whether Gu actually killed the horse, but what he was doing in Guangdong at all? After all, this job was pretty far from home? Nor was it what he had spent the last 13 years training to do. Why might a resident of Jiangsu (or northern China more generally) decide to move to a very different cultural and geographic climate in late 1924 or early 1925.

Gu did not leave us with a diary of his day to day thought, but one suspect that the very destructive Second Zhili–Fengtian War of 1924 may have had something to do with this decision. This conflict pitted the more liberal (western backed) Zhili faction against the conservative (Japanese backed) Fengtian clique for control of Shanghai (including both its rich legal and illegal trade networks). Things quickly escalated from there and the conflict became the bloodiest of Northern China’s many warlord conflicts. Almost all major urban areas in northern China suffered some damage as a result of this war, and in some placed the destruction was extensive.

It is not a surprise to discover that a number of individuals (Gu among them) decided that Guangdong looked like a good bet in 1924-1925. The Soviet backed clique of the KMT (headed by Chiang Kai Shek) was enjoying a moment of peace and security as its northern rivals ripped themselves apart.

It is likely that Gu (and others like him) believed that Guangdong was good place to start fresh. While a smaller port than Shanghai, the area was still connected to international trade. Even if the pace of social reform and economic growth was generally a little slower in Guangdong, by the 1920s it should have been possible to build a new life here.

Unfortunately Gu arrived just in time for another catastrophe, this one of an economic nature. The Hong Kong Strike of 1925-1926 was one of the most economically disruptive periods in the entire history of the Republic of China.

Not surprisingly this event had an important impact on a number of regional martial arts organizations. In fact, it affected pretty much everything in the local economy and society. Yet it is seemingly never remembered in our discussions of the era’s martial arts?

The origins of this trade embargo can actually be found in Shanghai and the aftermath of the Second Zhili–Fengtian War. Resentment of foreign interference was running high after this destructive conflict. Shanghai, which had both a substantial foreign presence as well as a highly unionized workforce, became the epicenter of this growing resentment.

The Communist Party sensed an opening and moved quickly to educated workers, draw up lists of demands and organize student protests. Initially much of this agitation focused on Japanese owned spinning mills. A series of escalatory confrontations at one mill led to a Japanese manager shooting and killing a demonstrator. At that point the city exploded like a powder keg.

Large groups began to protest in the international settlement. Demands ranged anywhere from a release of protesters held by the police to the end of extraterritoriality and even foreign investment in China. Eventually large numbers of protesters attempted to storm a British police station (they were intent of freeing some jailed comrades) which resulted in British, Chinese and Pakistani law enforcement officers opening fire on the crowd. There were dozens of casualties. Within days similar massacres played out in different cities around the country.

Very quickly the anger of the Chinese people shifted from the Japanese to the British. Hong Kong remained a center of the UK’s commercial strength in the region and it was a highly identifiable target. Both the KMT and the Communists initially supported plans to boycott foreign good and trade with Hong Kong. Businesses that flaunted the boycott found themselves the target of often violent reprisals.

The social effect of all of this was devastating. The economies of Guangzhou and Hong Kong were deeply linked and (truth be known) highly dependent on trade. When that trade was severed the entire area suffered a massive and immediate drop in GDP. This in turn led to a collapse in employment and government revenue. Probably 50% of the region’s GDP evaporated in a few months.

In a future post I plan on talking about how these events affected the Choy Li Fut, Hung Gar and Wing Chun communities. But for right now, let’s consider what this probably did to Gu Ruzhang. The entire reason that he had moved to the south was probably to get away from exactly this sort of social disruption. Further, he got a job as a low level clerk probably because he had the benefit a few years of formal education and there was not much else for a wandering martial artist to do.

After all, the military (traditionally the largest employer of martial artists) had long since been professionalized and the armed escort companies (the second largest employer of hand combat professionals) had been put out of business by cheap and reliable train travel about a decade years earlier. In short, the martial arts world of his father and teacher had ceased to exist. Gu was probably working as a filing clerk because he needed the job.

This was the basic situation before the local economy took a massive hit. One wonders whether rumors of his Kung Fu prowess began to emerge during this period because he was forced to fall back on his martial skills and public demonstrations to support himself. After all, the famous story of killing the horse with a single punch is, at the end of the day, a pretty typical example of a public performance where organizers are selling tickets and contestants are competing for money (all protests to contrary notwithstanding).

Fortunately Gu’s luck begins to improve at about this point in our story. Once again it is a shift in national politics that opens a new set of possibilities. With the major northern cliques left bloodied and exhausted from their recent confrontation, Chiang Kai Shek lost little time in exploiting his opening. Following the end of the Hong Kong Strike in 1926 (which had lasted substantially longer than he planned) his forces began the now famous “Northern Expedition.” This campaign allowed the general to consolidate large parts of China under his direct control.

Still, there is more to unifying a nation than seizing territory. The KMT created multiple programs to promote a sense of nationalism and shared identity. One of the more interesting of these (building off of the earlier success of the Jingwu Association) sought to use the traditional martial arts as a tool of state building.

Of course in the 1920s there was very little about the Chinese martial arts that was actually “unified” or “modern,” let alone supportive of the KMT. The Japanese had demonstrated that the martial arts could be a critical part of the nation building process, but to do this the government must first assert regulatory and ideological control over this section of civil society. In politics a message that cannot be scripted or guided is not a tool, it’s a liability.

The new organization meant to unify the martial arts community behind the aims of the state was the Central Guoshu Institute. The group was founded as the dust was still settling from the Northern Expedition and its headquarters were located in Nanjing.

Gu Ruzhang appears to have been hired on as a drill instructor at the Central Guoshu Institute soon after its creation. However, that is not where he would come to national prominence. Members of the Guoshu Institute realized that they needed to convince martial artists around the country to participate in their program (one that most boxers had been doing perfectly well without) if they were going to succeed. To spread their mission they organized the First National Guoshu Exam in October of 1928.

The novel undertaking was a three way combination of a Qing era military exam (minus the traditional emphasis on archery), a boxing tournament and a modern, spectator-centered, sporting event. The relatively young Gu Ruzhang entered the tournament and on its final day was named a “guoshi” or national warrior. At the time it was the highest honor that the KMT could award to a martial artist.

Gu Ruzhang: The South Bound Tiger.

The organization of the initial National Exam had been rushed. There were the sorts of problems with the format and programing that one might expect from a new effort. Still, many members of the audience found the entire thing enthralling. One of the most enthusiastic converts to the new Guoshu program was General Li Jishen. At the time he was the governor of Guangdong and Guanxi and the commander of the Eight Army.

Li decided that he would enthusiastically support the Guoshu initiative. It seemed to be the ideal way to strengthen and unify the area under his command. Of course the traditionally hierarchic structure of martial arts associations could also be converted into an inexpensive mechanism for spreading ones political influence throughout society.

He invited Gu Ruzhang and four other individuals to return with him to Guangdong where they would establish the Liangguang Guoshu Institute. Collectively these individuals became known in the press as the “Five Southbound Tigers.” Together they had an impressive background in the northern arts including Taiji, Bagua, Liuhe Quan, Cha Quan, a wide variety of weapons and of course Northern Shaolin.

This was not actually the first time that the northern arts were to be publicly taught in the south. That honor is usually awarded to the Jingwu Institute which had opened multiple clubs in the area in 1920 and 1921. It should also be remembered that, unlike most other areas of the country, the Jingwu Association in Guangdong remained strong until the Japanese invasion in 1938.

Unlike the Jingwu Association, the new institute was conscious of the need to recruit some southern stylists for the teaching staff. This went a long way towards not alienating the local population. It hired Zhang Liquan, a White Eyebrow expert, among a handful of others. Gu Ruzhang himself was well known for cultivating a positive relationship with a local Choy Li Fut clan. Still, the vast majority of the organization’s teaching efforts were to focus on the orthodox (e.g., northern) Guoshu curriculum.

General Li’s branch of the Guoshu Institute formally began accepting students in March of 1929. It had an initial enrollment of a little under 150 students and its offered classes 5 times a day (three two hour session and two one hour slots). Following the lead of the Jingwu Association, the new club made deals with local schools, government offices and companies to provide in house instructors for a set fee. For the most part it seems to have been government agencies that took them up on this offer. It appears that a very large percentage of their student base were workers from various KMT controlled offices. Initially enrollment was limited to men, but special classes for women were eventually created.

While enrollments were good, they were not spectacular. The fact that so many of the new students were employees of the KMT leads one to suspect that it was going to take the new organization a while to penetrate deeply into the already crowded local market for martial arts instruction.

Despite these shortcomings, or maybe because of them, the governor and the Liangguang Martial Arts Institute announced a road map to radically reform the martial arts of Southern China. The first stage of this process was the registration of all martial arts schools in Guangdong and Guangxi. The next step was to be a total ban on the creation of any new schools or associations other than those created by the staff of the Guoshu Institute. Lastly the organization would begin publication of a new martial arts magazine explicitly dedicated to advancing the nationalist “Guoshu philosophy.”

With the full power of the provincial government and the Eighth Army backing the orders, it seems at least possible that these policies could actually have been implemented. Clearly General Li Jishen was quite sincere in his desire to turn the local martial arts community into a tool to be exploited by the state. With perfect hindsight it is hard to see how the execution of such a plan could have been anything but disastrous for Guangdong’s flourishing indigenous martial arts community.

Political calamity intervened before implementation of the new policies could begin. In May of 1929 General Li Jishen resigned as governor and traveled to Nanjing with the intention of mediating a dispute between Chiang Kai-shek and the “New Guangxi Clique.” Negotiations between the groups went badly and Li Jishen was arrested and held until his eventual release in 1931.

General Chen Jitang was then appointed the new governor of Guangdong and Guanxi. One of Chen first acts was to eliminate his predecessor’s cherished Guoshu program. I suspect that this action was politically motivated. Perhaps he saw the organization as a threat, or maybe he did not want to align himself with a wing of the GMD that was so much under the influence of Chiang Kai-shek’s vocal supporters. Whatever the real reason, Chen claimed to be acting out of an urgent need for fiscal responsibility.

The total budget of the Institute was around 4,500 Yuan a month. This was a substantial figure, but probably in line with the costs of a major social engineering project like that which Li had envisioned. The Liangguang Guoshu Institute folded after a mere two months of operations, a victim of internal politics within the GMD.

The upshot of this rapid fall was that a number of prominent northern exponents were left unemployed and more or less stranded in Southern China. This seeming setback created new opportunities that spread the northern arts more effectively than anything the Guoshu Institute had ever managed to do.

After all, most of the instruction that the school had offered was focused on a handful of civil servants. This likely reflects the fact that it was government pressure and subsidization that supported the original Institute, not public demand. Chen’s forced dissolution of the Institute allowed its instructors to enter the much broader marketplace for private instruction. It was within these smaller commercial schools that northern styles, such as Bak Siu Lam and Taiji, really took hold and began to spread in the south.

Gu Ru Zang proved to be among the most influential of the remaining staff. In June of 1929 he created the Guangzhou Guoshu Institute. It seems likely that this new, smaller organization, had some level of official backing and that it clearly fell within the broader Guoshu movement led by the Central Academy in Nanjing. The group was housed in the building of the National Athletic Association. That said, the new institute did not continue the grandiose mission of its predecessor. It did not attempt to regulate or lead the local martial arts marketplace. It essentially became just one more martial arts school among many. Ironically that appears to have been the key to its long term success.

Conclusion: Gu Ruzhang as a Wandering Tiger

One might assume that after his return to the South, and his subsequent establishment of a successful martial arts institute, Gu would settle down. Unfortunately it was not to be. He left the region following the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931. I have not been able to locate precise information on what he did next.

In 1932 Ho Qian, a high official in Hebei Province, hired Gu to act as a head instructor at the Heibi Military Academy. Such appointments were very prestigious and highly sought after. This kind of government sponsorship was seen as legitimating the efforts of a martial artist. Gu also opened a traditional medicine clinic in 1932. Yet once again the Master showed no interest in putting down roots.

In 1934 he returned to the south, this time to receive an appointment as the Chief Guoshu Instructor for the Eight Army. This would be the last major assignment of his career. In 1938 the Japanese invasion reached Southern China. Most martial arts schools closed their doors or went underground. The Central Guoshu Institute retreated with the government to the far interior of the country.

In the early 1940s Gu Ruzhang announced his retirement from the world of the martial arts. At that point he disappeared from public view. I have not been able to find much information on the final years of his life. He is known to have died in 1952 and a few of his students have asserted that heart problems were to blame. He was only 58 years old at the time of his death.

Still, his career spanned three decades in which the traditional martial arts were transformed, modernized and socially repositioned for even greater success in the future. Gu taught literally thousands of students in his lifetime and played an important role in preserving and passing on China’s martial culture.

It is certainly interesting to watch how the Chinese martial arts evolved throughout his life. As a child they were the essential skills of bandits and paramilitary guards. Later they fell on hard times. Then in the 1920s and 1930s the traditional combat systems were systematically re-imagined as an aid in building and promoting a new vision of Chinese nationalism. Each of these shifts reflected larger changes in the China’s economic and political situation. These in turn manifested themselves in very specific ways in Gu’s life and career.

August 2, 2013 at 12:39 pm

Why is it that on the Internet, the pictures of Gu Ruzhang are also associated with xingyi quan master Guo Yunshen (1829-1900)? Seems to me that these are indeed early 20th century pictures, so it could not be Guo Yunshen. Do you have an explanation for that?

August 2, 2013 at 2:36 pm

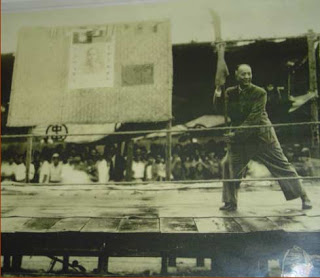

I have seen that in a couple of places as well. To be perfectly honest I have no idea how the two gentlemen became conflated. They don’t really look anything like each other (at least not from the pictures I have ever seen). Maybe it was the fact that Guo Yunshen was known for his “crushing fist” and there is that great picture of Gu Ruzhang doing his Iron Palm demonstration? Its not much, but its the only thing I can think of off the top of my head.

August 6, 2013 at 1:27 am

I think that pictorial association is strictly an error at best. Great-Grandmaster Ku (Gu) did not profess to be a Hsing Yi exponent nor was he! Great-Grand Master Ku (Gu) was famous for wide spreading the Northern Shaolin Gate style to other parts of China, and was appoint by the government to seed the Northern Shaolin Art to the southern part of China. This is what he is most famous for! and why should continue be recognized by our Chinese Martial Arts global community.

August 12, 2013 at 5:11 pm

Hsing Yi was part of Gu Ru Zhang’s training and techings:

HSING YI SCHOOL LINEAGE

• Ji Long Feng

• Cao Ji Wu

• Dai Ling Bang

• Li Nen Ran

• Kuo Yun Shen & Li Kui Yuan

• Sun Lu Tang

• Kuo Yu Chang

• Yim Shan Wu

• Wong Jack Man

Greg Hayes

February 7, 2015 at 1:00 pm

an error at best is the best possible reason. also names are /slightly/ similar.

August 18, 2013 at 11:51 pm

Very nice, thank you for writing an article that’s simple and to the point about GM Gu. Kudos and keep up the good work!

August 19, 2013 at 5:13 am

Thanks! I’ll try.

August 21, 2013 at 2:15 am

If you are interested in Gu Ruzhang you may also want to check out this recent post at the Brennan Translation Blog. Its an English Language edition of his 1936 Taiji Manual.

http://brennantranslation.wordpress.com/2013/08/20/the-taiji-manual-of-gu-ruzhang/

August 24, 2013 at 2:16 am

thanks for sharing this

September 8, 2013 at 10:25 pm

I think that is Chen Pan-ling in the third picture.

July 2, 2015 at 12:16 am

Great article – thanks for filling in some of my lineage history!

August 10, 2019 at 11:44 am

Excellent article very interesting and informative thank you