Introduction: Critiquing the Conceptual Coherence of the Martial Arts.

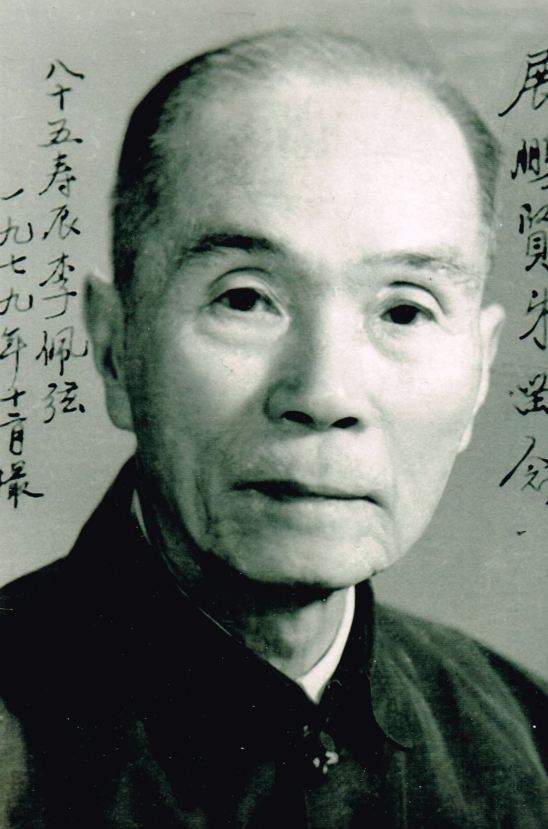

In this installment of the “Lives of the Chinese Martial Artists” series we will be looking at the life and career of Li Pei Xian. While a regionally important individual I doubt that many of my readers will be familiar with this name. Nevertheless, I am very excited to be able to include him in our growing collection of biographical sketches.

The central purpose of this series of posts is to remind modern readers of the variety of life experiences and careers that were experienced by late 19th and 20th century Chinese martial artists. For current students, both in China and the west, this is a very real blind spot.

The problem starts with our terms. We assume that we know what the “martial arts” are. From our perspective they are a single, easily identifiable, activity. Individuals who are involved in the martial arts are easily identified by their colorful traditional uniforms and can be found carrying on a certain type of economic activity in any self-respecting strip mall. Further, modern martial artists usually self-identify as such. They even have trade organizations and publications that usually include the words “martial arts” in their titles to limit the possibility of confusion.

The situation in 19th century China was very different. I would go so far as to guess that many, maybe even most, individuals who studied martial skills would have been surprised, and in some cases even offended, to discover that they were mere “martial artists.” When asked about their identity most of these people would have responded that they were professional soldiers, night watchmen or runners for the local yamen. Many would have been farmers who out of necessity joined a local crop watching society. Being a “respectable peasant” was a much higher class occupation than being a boxing instructor or guard. Others may have been traditional medical doctors or opera performers. In a few cases you might even encounter members of the gentry who studied boxing or archery as a form of self-cultivation and entertainment.

If you would have grouped these individuals together and told the soldier, the farmer, the opera singer and the gentleman that the skills they practiced were all functionally equivalent or interchangeable they would have been very confused. The idea of the “martial arts” as we use it in contemporary conversation is a modern construction. These things look similar to us because of our modern perspective. Indeed many of these categories got mixed together in the early 20th century.

If you search for an 18th century Chinese word that encompassed all of these skills and life experiences what you will quickly discover that there wasn’t one. The arts of war practiced by soldiers were conceptually distinct from “Quanban” (an archaic term favored by the Qing administration translating roughly to “Fist and Pole”) which by definition could only be studied by a civilian. And all of that was quite distinct from “medicine” and “theater training.”

Later in the 19th century all of this starts to change. As China came into deeper contact with the western world conceptual categories were loosened and rearranged. Ideas like “Chinese culture” and “traditional culture” took on a new relevance when there was an accessible alternative. Suddenly categories like “traditional dress,” “traditional painting,” “traditional music” and even “traditional physical culture” came into daily use.

By the turn of the century, and even more so in the 1920s, certain intellectuals were scrambling to collect the remains of China’s “traditional culture” and preserve elements of it for posterity. Yet this entire exercise is predicated on the creation of categories of thought and types of associations that could not have existed a century before. The modern world never really preserves the past, it recreates it.

This is why I personally tell people that the traditional Chinese martial arts are a product of the late 19th and early 20th century. Were there schools of boxing and wrestling that existed before this? Certainly. We have wonderful accounts of martial performers in the Song dynasty, and many still extant manuals on boxing and fencing from the Ming period. Daoist medicine involving gymnastics and breathing exercises goes back even further. But thinking about the “martial arts” as a distinct, coherent, conceptual category that unites all of this within a world of civilian commercial activity? That is a product of the late 19th and early 20th century.

This is why the exercise behind the “Lives of the Chinese Martial Artists” series is so important. It helps to explore the variety of life experiences that existed in the past as well as allowing us to study the unification and modernization of the traditional fighting styles.

Indeed, the traditional Chinese arts have gone through an impressive conceptual evolution. This has not always been a smooth process. There have certainly been some episodes of high drama. One can almost follow the story of the creation and the evolution of the modern “martial arts” like the plot of a novel.

A wide variety of mostly unnamed folk combat traditions have existed from time immemorial. These skills have formed an important means of escape for youth from the countryside looking to move and better their lot in life. However, with the advent of modernization, different sorts of movement and economic activity are now possible.

Responding to this challenge the “martial arts” reorganize themselves and gain conceptual coherence. In so doing they reposition themselves from “local traditions” to elements of “national culture.” This was not possible in previous eras as “the nation,” as a conceptual category, did not yet exist. While initially resisted by some, this movement of the traditional fighting style proves to be successful. It was actually so successful that factions within the state (who were actively looking for tools to extend their reach into local society) decide that they could use these newly minted “traditional arts” to craft and reinforce their preferred vision of popular political identity.

However, alignment with a single political faction creates the opportunity for a violent backlash once other forces come to power (as has happened multiple times, including during the Cultural Revolution). Finally, as the economy advances new types of problems emerge. Now the martial arts are called upon to address the problems that inevitably accompany rapid urbanization and the growth of a fast paced capitalist society.

The flexibility of the Chinese martial arts in the face of this degree of social change is nothing short of amazing. No character better exemplifies these 20th century trends than Master Li Pei Xian. While less well known in the west his own stories mirrors each of these larger twists and turns with uncanny precision.

Li Pei Xian: Local Boy Makes Good

I first encountered Li Pei Xian while researching the history of the Foshan branch of the Jingwu (sometimes Chinwoo or “Pure Martial”) association. Foshan plays an important role in the evolution of Guangdong’s modern martial arts. As I have discussed elsewhere, one cannot understand the history of this town’s Republic era market for martial arts instruction without coming to terms the role of the local Jingwu chapter.

After the Hung Sing Association, it was the largest martial arts club in the town. While Hung Sing appealed to the traditionalist sentiments of working class individuals, Jingwu, which had been influenced by the YMCA movement in Shanghai, sought educated middle class students. More than any other force in China at the time, it sought to modernize the martial arts and to place them in the service of the nation.

The Foshan branch of the movement was large, with thousands of students and dozens of instructors. It even succeeded in embedding its members as physical education instructors in local schools. Jingwu is also critical to the history of Southern China’s martial arts because of its longevity. While the Association ceased to exist in most of the country after a financial disaster in 1925, the Foshan branch was well funded and very popular. Li Pei Xian, its longtime “Director of Athletics and Martial Arts,” was at least partially responsible for this. As a result the Foshan Jingwu actually managed to survive into the post WWII period.

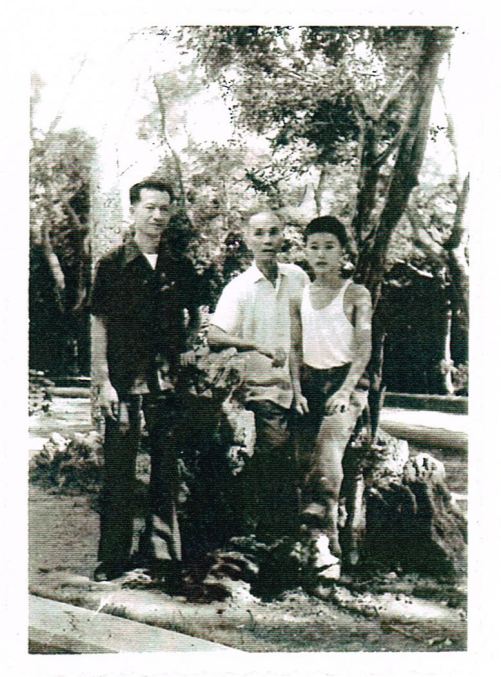

Li Pei Xian (1892-1985) was born at the end of the Qing dynasty in Xinhu, a town in the Jiangmen area of Guangdong. His beginnings were rather unremarkable and Jiangmen was economically depressed for much of the early 20th century. Luckily Li was interested in the martial arts as a youth and was able to study Hakka Kuen. This art, which originated within the Hakka ethnic minority community, is a classic example of a traditional southern style. It seems that like so many other country boys with few prospects Li turned to the martial arts both as a form of education and as a means to move up in the world and better himself.

His fortunes began to look up in 1910 when he moved to the bustling, dangerous, metropolis that was Shanghai. Many of the stories of rural immigrants to this city end in despair and tragedy. Entire industries were devoted to fleecing hapless and naïve newcomers who arrived seeking opportunity and employment.

Li seems to have avoided the worst of this. In fact, his background in the martial arts may have even given him a leg up in his new home. Many important boxers were in and around Shanghai in the first few decades of the 20th century. This would have been an exciting place to live for any martial artist. Li appears to have thrown his lot in with the newly created Jingwu Association. This group was created the same year that Li arrived in Shanghai allowing him to get in on the “ground floor” of a good thing.

In fact, Li likely even had a chance to meet the martial saint Huo Yuanjia, who died on August 20, 1910. While formally the chief instructor of the Jingwu Association Huo died very shortly after its creation. His institutional contributions were limited. However, once the story of his supposed murder by “scheming Japanese imperialists” began to spread, Huo Yuanjia was elevated in the national consciousness to the status of a god.

A dedicated publicity campaign engineered by the young business minds behind the Jingwu Association ensured that the story spread. Huo’s supposed martyrdom helped to make the group China’s first truly national martial brand. A heady combination of sanitized and modernized martial arts, nationalist mythology and sophisticated marketing meant that within ten years every major city in eastern and southern China had a branch of the Jingwu association.

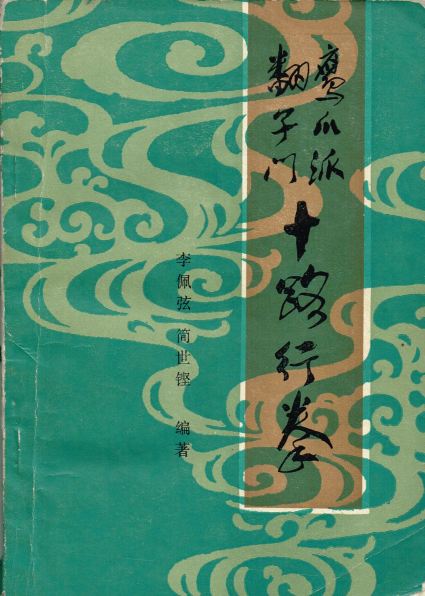

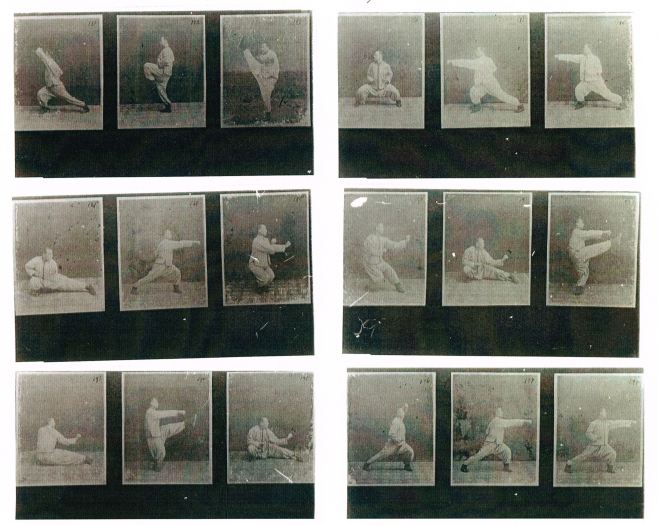

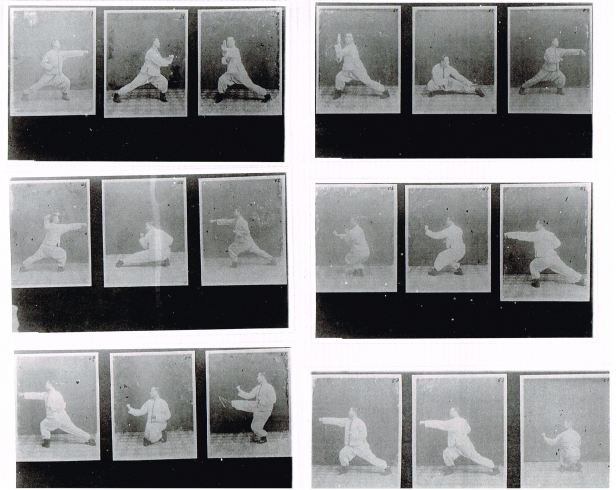

Li Pei Xian had bet on the winning horse. He was already a trained martial artist, but of course it was necessary to retrain and certify in Jingwu’s northern styles and “scientific methods” before he could begin to move up in the organization. By 1916, he had completed the six years of study necessary to become an instructor within that system. He studied Shaolin boxing with Zhao Lian He, Northern Mantis with Lo Kuang Yu and Eagle Claw from Chen Zi Zheng. He also mastered a large number of miscellaneous hand and weapons forms.

Li was hired directly by the Jingwu Association central office after receiving his advanced level certification and he later worked at the organizations headquarters in Shanghai. Of course there was always more to Jingwu than just the martial arts. It was meant to be a “one stop shop” for middle class entertainment, so it actively promoted modern and western pastimes. In addition to teaching martial arts Li also acted as a director in the dance and photography departments.

This wide range of skills would later be critical to his career advancement. Jingwu encouraged its member to become renaissance men (and women). Li was no exception.

Founded in 1920 (though classes did not start until 1921) the Foshan branch of the Jingwu association would become one of the organization’s most prosperous and innovative chapters. It was also one of the longest lived. In fact, it still exists today in a modified form.

Unfortunately this branch did not enjoy overnight success. For reasons that go well beyond the scope of this article, after an initial burst of enthusiasm Jingwu struggled to establish itself in Foshan. The situation deteriorated rapidly over the first few years. By about 1923 the local organization had almost completely ground to a halt.

The situation only began to recover after a strategic change in leadership. In 1922, Zhong Miao Zhen, who had been a very passive leader, resigned as president of the Foshan branch. He was replaced by the much more dynamic and capable Liang Du Yuan. Liang was a local businessman with excellent organizational skills and a burning faith in the new group. He had suffered from ill health until he joined the association and began to intensively study martial arts. As his health improved he became an enthusiastic advocate of Jingwu’s mission of “national salvation.” Liang would remain the president until the Japanese invasion in 1938. Under his leadership, the Foshan branch finally gained a central place in the local martial arts subculture.

Upon taking office Liang Du Yuan began an aggressive policy of community outreach. Under his watch the organization opened schools, free medical clinics, hosted western style sporting events, published newspapers, and held classes on topics as diverse as music, painting and public speaking. The broader Jingwu Association had always found it necessary to use these more accessible events to attract urban middle class investigators. Those that stayed could then be convinced to enroll in martial arts classes.

The Foshan Jingwu Association went well beyond this general pattern. During its first few years the organization had been plagued by the popular perception that it was populated by outsiders who were hostile to the local community. What is more, that perception may not have been entirely incorrect. Liang decided that the key to success was to embed his organization within the local community by providing a wide range of subsidized opportunities to the middle class, such as roller skating expeditions or photography classes, and highly publicized charitable projects for the less fortunate. This allowed the organization to begin to build what sociologists call “social capital,” or mutual bonds of trust and reciprocity. As people became more familiar with the group and its aims they came to trust it and viewed it as a part of the local community.

Building these bridges proved to be absolutely critical. Not only did student enrollments begin to rise, but the Foshan branch secured sources of local support and income that were not dependent on Shanghai. As a result, the collapse of the national Jingwu movement in 1925-1926 had little impact on the Guangdong chapters.

Other changes in the chapter’s organization were also made. In 1923, Li Pei Xian was transferred to Foshan where he remained as the “Athletics and Martial Arts Director” until 1938. It is interesting to note that while the branch president was chosen locally the director of athletics (essentially the chief martial arts instructor) had to be appointed directly by the central office in Shanghai. In fact, all of the martial arts instructors in the Foshan branch came from Shanghai. This appears to have been a critical aspect of how the central Jingwu Association ensured the integrity of their brand.

The fact that Li was actually from Guangdong, spoke Cantonese and had a background in a southern boxing style may have helped him gain credibility within Foshan’s crowded martial marketplace. However, his actual teaching activities did not deviate from the orthodox, strictly northern, Jingwu teaching curriculum.

One of his first reforms after taking office was to create a number of “small groups” within the broader student body of the Foshan Branch. These structures were essentially study groups designed to keep students motivated, allow for mutual support and a sense of belonging. It is easy to see how these qualities, which are still essential to successful martial arts schools today, could become lost in the Jingwu Association’s more megalithic teaching structures. These groups were a great success and more were created from 1924-1926.

Li also oversaw the successful introduction of Taiji to the Foshan Jingwu curriculum. This art, in all of its various guises, has become spectacularly popular throughout China and the Pearl River Delta region is no exception. The regional success of Taiji demonstrates once again the critical role that the Jingwu Association played in bringing northern styles of hand combat to the south.

Li was also responsible for the martial arts columns published monthly, then weekly, in the branch’s newspaper. While in Foshan he served both as an editor and author for his organization main mouthpiece. Li should probably receive much of the credit for the success that the Foshan Jingwu branch eventually enjoyed.

Of course Li Pei Xian’s career extended far beyond his involvement with this one organization. The Japanese invasion severely hampered the functioning to the Foshan Jingwu Association. In 1938 he resigned his position and left to join Gu Ru Zhang’s Guangzhou Martial Arts Association where he is supposed to have trained an anti-Japanese Dadao (“military big saber”) squad.

Government Support, Retrenchment and Rehabilitation

I have not been able to track down much information on Li’s career between 1945 and 1949. He did not follow the lead of so many other traditional masters who fled Guangdong after 1949. If anything his career actually became more active and better supported following the communist takeover.

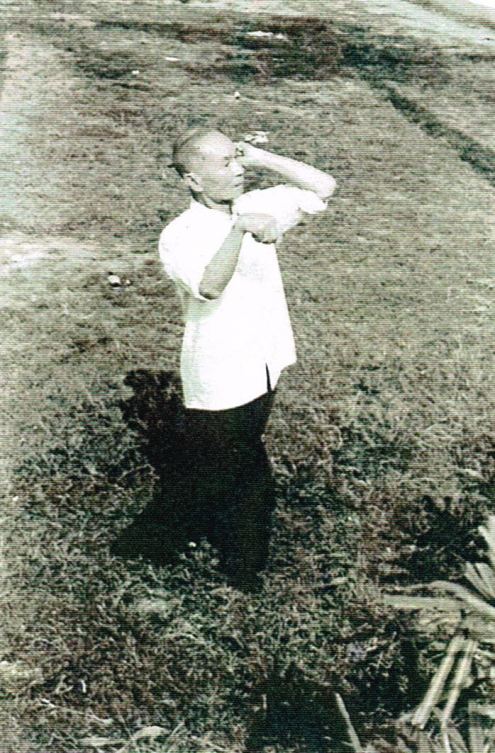

Prior to 1938 Li had been best known for his classic Jingwu Eagle Claw and Northern Shaolin techniques. However, after 1949 he became an advocate of Wu style Taiji in Guangzhou. In fact, Li quite successfully negotiated the change of regimes that ended the careers of so many other local martial artists. He achieved a degree of official recognition and government support that he had never enjoyed during the 1930s (when the KMT’s Central Guoshu Institute was attempting to craft its own martial arts movement). In 1957 Li even led the Guangdong provincial martial arts team to Beijing to compete in the National Martial Arts Award & Observation Conference.

In 1959 he was appointed the director of Physical Education Teaching and Research at the Guangzhou College of Traditional Medicine. There he established a martial arts team which continued to campaign for the overall health benefits of China’s traditional physical culture. In 1961, he began to offer courses in Qigong, in conjunction with the provinces Department of Health, at a number of universities and high schools.

This interlude is quite significant for a number of reasons. As both David Palmer and Nancy Chen have demonstrated, the 1950s were something of a turning point for traditional Chinese medicine. While the Communist Party had traditionally favored western “scientific” medicine, the debate between the “foreign experts” (many of whom were sympathetic western doctors) and the “Reds” (local communist cadres) motivated them to take a second look at traditional Chinese medicine. Traditional movements and breathing exercises, termed “Qigong” by local medical officials, were vastly cheaper than western medicines.

Of course creating a new branch of traditional Chinese medicine, freed from “feudalism” and “superstition,” was not an easy or quick process. New clinics and departments of medicine were founded. These employed a wide range of medical doctors, traditional Qigong practitioners and quite a few martial artists. Li advanced his career in the late 1950s by moving into this newly opened, relatively well funded area. In short his sudden interest in TCM reflects both broader social trends and the funding priorities of the Chinese state.

The real tragedy of this burst of government support of Qigong in the 1950s and 1960s is what happened next. The Red Guards of the Cultural Revolution were in no way convinced that Chinese medicine had freed itself from its superstitious and un-scientific past. As a result many doctors, martial artists and even healthcare administrators’ suffered their wrath. It is not clear exactly what Li’s specific situation was like but he appears to have survived the Cultural Revolution relatively unscathed.

In 1960, 1962 and 1977 he released major works on Qigong and Taiji, all published by the People’s Sporting Press. In 1982, just at the start of the Kung Fu and Qigong “Fevers” he emerged as an expert on the national stage and published an extended series of articles on Shaolin Boxing in Wulin magazine. In the years before his death he produced literally dozens of articles on different aspects of martial arts for various publications.

Conclusion

Li’s life story clearly illustrates the opening to the broader national culture that Guangdong’s martial artists faced in the early 20th century. Born in a relatively undeveloped area and educated in Hakka Kuen, this young martial artist went on to make a name for himself promoting Taiji and traditional medicine on the national stage. It seems unlikely that any of this would have been possible without the Jingwu Association. While its classes mostly catered to the urban and well off, within martial arts circles it still filled the traditional role of providing a path for advancement for young men of talent who lacked resources.

Just as important is what Li’s career illuminates about the evolution of China’s traditional fighting arts during the 20th century. Over the span of his lifetime we have seen the arts move from a strictly local practice, to one with implications for regional and even national identity. New and sophisticated forms of management were introduced into hand combat organizations including modern advertising, funding and franchising structures. All of this allowed the “traditional arts” to be expanded on a vast commercial scale.

Once these arts had been established in society they became available to the state as a tool to advance its own agenda. That included the crafting of political identity during the Republic period (where the state supported Guoshu) and the Cultural Revolution (when the party turned on the traditional arts to promote “scientism”), as well as advancing economically and socially driven agendas (e.g., state backing of Qigong and Taiji during the 1950s and 1980s.)

In each of these cases officials, public intellectuals and hand combat teachers have struggled to redefine how we understand the term “martial arts.” Economic development and the evolution of efficient markets have also had a huge impact on this process. All of these factors are illustrated in the life and career of Li Pei Xian.

November 27, 2013 at 3:55 am

damn fine piece of writing – thanks