Introduction

My original plan for the day included writing a conference report on the recent Martial Arts Studies gathering at Cardiff University (which, as always, was a blast). However, when I opened my email this morning I found a note from Paul Bowman reminding me that today is the 44th anniversary of Bruce Lee’s death. Paul was kind enough to send me a copy of a draft chapter that he had written for the occasion and offered to share it with the readers of Kung Fu Tea as a guest post. Normally I would post this early on Friday morning, but given that today marks the actual anniversary, I thought it would be better to break with tradition and get this up a bit early. In addition to his more recent work on Martial Arts Studies, Paul Bowman has written multiple books on the cultural and social significance of Lee’s films and martial arts career. As such, he is ideally situated to discuss Lee’s continuing legacy. Enjoy!

Bruce Lee: Cult (Film) Icon

Paul Bowman

Cardiff University

Draft chapter written for a collection on cult film, edited by Ernest Mathijs and Jamie Sexton.

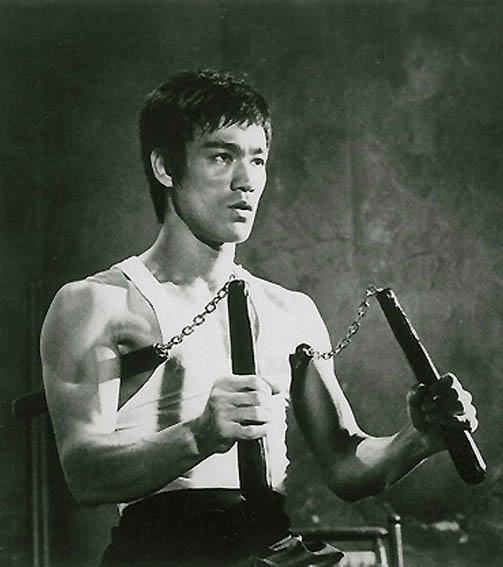

I write these words on the 44th anniversary of the death of Bruce Lee (July 20th 1973). When he died I was two years old. Lee was at the height of his fame. At the time of his death, his fourth martial arts film, Enter the Dragon, was being released internationally. He was already well known around the world: in Asia he was stellar; in the West his films had a growing cult status (Hunt 2003; Teo 2009; Lo 2005). For all audiences, he was becoming the exemplar of a new type of masculine cool invincibility – a simultaneously impossible yet (possibly – almost) achievable ideal (Chan 2000; Nitta 2010). It was impossible because Lee was invincible, but it seemed (quasi) achievable because Lee’s invincibility was always shown to be the product of dedicated training in kung fu. So, his image wasn’t simply fictional. His image wasn’t merely fake. He wasn’t magic. He was simply a kung fu expert. This meant that all you had to do to be like him was train. Anyone could train. Everyone could train. So, very many people did. And this became known as the ‘kung fu craze’ of the 1970s (Brown 1997).

At the time of his death, Enter the Dragon was about to push Lee into the mainstream of global popular consciousness. If up until this point he had achieved ‘cult’ status in the West, he was about to attain the status he had already attained across Asia: superstardom. But this would not involve selling out or dampening down any of the ‘cult’ features that characterised his kung fu films. Rather, Lee’s success would amount to the international explosion of martial arts film and martial arts practice: its leaping out from the shadowy margins and into the bright lights of the mainstream.

This explosion is still referred to as the kung fu craze of the 1970s. Bruce Lee was the image and the name that exemplified this ‘craze’. There were other martial arts stars, of course, both before and after Bruce Lee; but he was and remains the quintessential figure. His name still sells books. Documentaries are still being made about him (Webb 2009; McCormack 2012). Martial arts magazine issues that have his image on the cover still sell more copies than those which don’t. Blog entries about him still generate spikes.[i] He is still credited as an inspiration by athletes, boxers, UFC and MMA fighters, and martial artists of all stripes (Miller 2000; Preston 2007). YouTube continues to throw up new Bruce Lee homages and montages. Computer games still have Bruce Lee characters. He is still used in adverts. He is universally regarded as having been a key figure for non-white film and TV viewers of the 1960s and early ’70s – a kind of oasis in a desert of white heroes and (at best) blackspoitation (Prashad 2003, 2002; Kato 2007; Bowman 2010; Chong 2012). He was immediately (and remains) a complex and important figure for diasporic ethnic Chinese the world over (Hiramoto 2012; Teo 2013; Marchetti 2001, 1994, 2012, 2006). And he forged the first bridge between Hong Kong and Hollywood film industries.

There is so much more to say about all of this. I could go on with this list. But I have said much of this before (Bowman 2010, 2013). So instead, having set the scene, however fleetingly, let’s pause to reflect on whether this makes Bruce Lee a ‘cult’ figure.

In order to focus principally on Bruce Lee as a cult icon, we cannot undertake too much of a digression into a fully elaborated discussion of the controversial and problematic term ‘cult’ in film and cinema studies (Shepard 2014; Mathijs and Mendik 2008; Mathijs 2005). Suffice it to say that in and around film studies the ongoing academic disputes about the notion of ‘cult’ centre on the question of what makes something a cult object. Is the thing that makes an object (normally a film but sometimes an actor, director or even genre) into a ‘cult’ object to be found in the properties of the object itself, or in the status of that object in relation to other objects, or in an audience’s response to it?

There is a lot of disagreement about this. My own sense is that cult is principally a useful descriptive term, but that it is less useful analytically. Nonetheless, in attempting to think about Bruce Lee through this lens, some hugely stimulating insights can emerge. In what follows, I will principally concern myself with responses and relations to the cinematically constructed image of Bruce Lee, rather than with attempting to adjudicate on the matter of whether this or that feature of his films (Barrowman 2016) or his cinematic, media or spectacular image fit into his or that categorisation or definition of ‘cult’ or ‘not-cult’. So rather than worrying about taxonomies, I will translate the ideas and associations of the word ‘cult’ into the sense of a variably manifested passionate relation to or with something – in this case, the textual field of objects known as ‘Bruce Lee’.[ii]

I do this because there is not now and there never has been a single or singular cult of Bruce Lee. It has always been cults, plural. The ideas, ideals, injunctions and aspirations associated with Bruce Lee were always multiple. In effect, there have always been several Bruce Lees – different Bruce Lees for different people. Lined up side by side and viewed together, the ‘Bruce Lee’ constructed by each group, audience or constituency often appears, on the one hand, partial and incomplete, yet on the other hand, larger than life and impossibly perfect. There are biographical, technological and textual reasons for this.

Firstly, Lee died unexpectedly, very young, in obscure circumstances, and for a long time afterwards much of his life remained shrouded in mystery – a mystery that largely arose because of a lack of reliable, verifiable information about him, his life, and the circumstances of his death. It is arguably the case that his family, their advisors, and his estate made a series of less than ideal decisions around the dissemination of information about Bruce Lee both in the immediate aftermath of his death and in the subsequent years and even decades (Bleecker 1999). These decisions all seem to have arisen from a desire to paint Bruce Lee hagiographically, as a perfect figure, a kind of saintly genius. Somewhat predictably, then, other voices have more than once come out of the woodwork to make somewhat contrary claims and to paint Bruce Lee in rather different lights . Through all of the mist and murk, one of Lee’s many (unauthorised) biographers, Davis Miller, makes an important point when he observes in his 2000 publication, The Tao of Bruce Lee, that surely there has been no other 20th century figure, so globally famous, about whom so little was actually known for so long (Miller 2000; Bowman 2010).

The film theorist André Bazin might have disputed such a claim, however. For, as he argued when discussing the cinematic images of Joseph Stalin, the cinematically constituted, disseminated and experienced image does much to create a kind of double or doubling effect (Bazin 1967:1-14). Of course, there may be a world of difference between Bruce Lee and Joseph Stalin, but Bazin’s observations can be applied to the figure that viewers felt they experienced when they experienced Bruce Lee. Indeed, it can be extended to apply to many other cinematic or media experiences of many other kinds of celebrity image too. The logic is this. Firstly, the cinematic image can make the figure seem larger than life. Baudrillard would call this ‘hyperreal’: more real than real (Baudrillard 1994). But Bazin also notes that the image on the cinema screen is, in a way, already dead, absent, out of reach, ‘mummified’. Yet, at the same time, and paradoxically by the same token, the nature of the cinematic image can make us feel we personally have intimate, personal, access to the person we are watching (Bazin 1967: 1-14; Chow 2007: 4-7).

These kind of observations about the cinematic image can serve as an entry point into thinking about the ‘technological’ reasons why there has never simply been one cult of Bruce Lee, but always more than one. We each see a very distant, larger than life figure, and yet we can also come to feel that we have an intimate insight into him – whatever that may be. He is there, and we can see what he is saying and doing; but he is gone, and we have to construct an interpretation.

This is where the textual or semiotic dimension becomes fully active. For, like any other media image, ‘Bruce Lee’ is essentially and irreducibly textual. When we think of or speak about Bruce Lee we are dealing not with one single or simple thing, but with complex pieces of textual material, woven into different textual constructs (films, documentaries, books, magazines, posters, anecdotes, memories). In fact, taken to its most ‘radical’ extreme, the theory of textuality essentially dispenses with the need for there to be an actual ‘text’ (such as a film, a book or a magazine article) in front of us at all. For, as elaborated by Jacques Derrida, the theory of textuality (aka deconstruction), holds that for each and every one of us the entire world is a text. We relate to everything the same way we relate to texts: we look, we listen, we think, we try to interpret, to make sense, to extract or establish meaning, and so on. According to the infamous phrase of Derrida (who was the most famous proponent of textuality as an approach to more or less everything), ‘there is nothing outside the text’ (Derrida 1976: 158-9).

Whether we go this far or not, according to most theories of text and textuality, the meaning of any given text is produced in the encounter with the reader. So, although the creators of any given text (literary, cinematic, TV, radio, etc.) will have had intentions, and will have wanted to create certain effects and induce certain responses, the buck stops with the reader, or the person who experiences these devices and combinations of elements. Accordingly, whilst some viewers may watch Bruce Lee’s filmic fights with his opponents and find them thrilling, tense, exciting, brilliant, even tragic, other viewers may find them boring, turgid, unintelligible, or even comical, and so on. Elsewhere in his acting, where some may perceive ‘cool’ others may see ‘wooden’; where some may perceive genius others may see idiocy.

Nonetheless, despite the range of meanings that could be attached to any aspect of Bruce Lee, it is certain that he had a massive impact. Although many in the Western world had seen ‘Asian martial arts’ on TV and cinema screens more and more since the 1950s (most famously perhaps in the TV series The Avengers and the James Bond film, Dr No), the effect of Bruce Lee on many viewers was instant and transformative. More than one documentary about the impact of Bruce Lee contains newsreel footage showing children and young teenagers leaving cinemas and movie theatres in the UK and US and performing the cat-calls, poses and attempting to do the flashy moves and kicks of Bruce Lee (BBC4 2013). In fact this scenario has come to constitute something of a ‘creation scenario’ in stories about the birth of what has long since been referred to as the ‘kung fu craze’ that swept through the US, Europe and much of the rest of the world, starting in 1973 (Brown 1997).

This was the year of the box office release of Enter the Dragon – a film that is notable because it was the first Hollywood and Hong Kong co-production, the first Hollywood film explicitly framed as a ‘martial arts’ film, and perhaps the first ‘formal’ introduction of many Westerners to the imagined world of Asian martial arts (Bowman 2010). It is also the year that Bruce Lee died in obscure circumstances. In many countries news of Bruce Lee’s death came out shortly before the film was actually released (Hunt 2003). All of which immediately made both the film and the man extremely intriguing. It is true that this was not the first martial arts film that had been available to audiences in the West. Several Hong Kong martial arts films had been successful in the US before. Indeed, it was their increasing success that had given Hollywood producers the confidence that this venture could be successful in the first place. But Enter the Dragon is without a doubt the most important martial arts film of the period, precisely because of its mainstreaming of Asian martial arts.

There are perhaps no rigorously scientific ways of establishing ‘importance’, ‘effect’ or ‘influence’ in the realms of media and culture (Hall 1992), but it can be said (with the benefit of hindsight) that from the moment of the release of Enter the Dragon it was absolutely clear that Bruce Lee was not merely influential but actually epochal. The historian, philosopher and cultural critic Michel Foucault came up with the notion of a ‘founder of discursivity’ (Foucault 1991). For Foucault, a founder of discursivity is something or someone that generates a whole new discourse, or that radically transforms an ongoing discourse. Although not discussed by Michel Foucault, my contention is that Bruce Lee should definitely be accorded the status of founder of discursivity.

The meaning of the term ‘discourse’ in this sense is quite precise. In the tradition of Foucault, a discourse is also but not only a conversation. Discourses in this sense also involve actions. For example, the discourse of architecture is not the conversations and arguments of architects, town planners, residents’ associations, lawyers, and so on. The discourse of architecture also refers to the processes, practices and results of these conversations and arguments: what buildings look like, how they are made, the changes in their styles and configurations, and so on. In Foucault’s sense, there are discourses in and of all things: law, religion, science, fashion, music, taste, you name it. So, a founder of discursivity may be identified in a person (for example, Elvis or Jimi Hendrix), or in a technological change (the electrification of music). The point is, we are dealing with an intervention that disrupts and transforms states of affairs. Bruce Lee was precisely such a disruption and transformation.

Let us return to the mythic scene of our origin story: the excited or excitable young viewers of a new Bruce Lee film, who have just left the cinema. They are not merely discussing the films. They make cat-calls. They try to throw kicks and punches in ways that two hours previously were completely unknown to them but to which they have just very recently been introduced and instantly become accustomed. What is there to say about this scene or situation?

Bruce Lee made only four and a half martial arts films before he died. He only used his signature screams and cat-calls for dramatic cinematic effect within those films. There is no evidence that he made his signature noises off-screen. Moreover, few cinematic or actual martial artists ever really followed Bruce Lee in using these kinds of noises in fight scenes, never mind in sparring or in competition. If and when such mimicry occurs, it is always in some sense what Judith Butler would call a ‘parodic performance’. And yet, to this day, when children in the playground strike improvised/invented ‘kung fu’ poses and throw what they think might be cool kung fu shapes, they still very often make the Bruce Lee cat-calls, screams and kiais – in performances that are in one sense parodic but in another sense completely sincere.

Evidence for this claim is anecdotal, of course. But I often observed it personally at my own children’s primary school, four decades after Bruce Lee’s death. At the same time, people from both my own and other countries have recounted the same observation to me. Of course, there may be various kinds of confirmation bias at play here. I may actually only be remembering a highly select few instances, and blowing them up, out of all proportion, while forgetting or ignoring cases where children’s martial arts play is not accompanied by Bruce Lee sounds. Similarly, my interlocutors may be telling me what they think I want to hear. But, unlike trying to establish ‘influence’ and ‘effect’ directly, perhaps a research project could be constructed that could explore what children ‘do’ when they strike ‘martial artsy’ poses. And my hypothesis would remain that they very often make noises that can directly and unequivocally be traced back to no one other than Bruce Lee. The fact that few such children are likely to have any conscious knowledge or awareness of Bruce Lee makes this even more interesting. But, in such a situation, are we still dealing with a cult? And what is the relation of any such conscious or unconscious cult with ‘cult film’?

Bruce Lee’s films constituted an intervention, definitely. A transformation, certainly. In the realms of film, Bruce Lee’s fight choreography changed things, raised the bar, set new ideals in film fight staging. But this remains in the realm of what we might call ‘film discourse’ or ‘film intertextuality’, relating as it does to the ‘internal conversations’ and changing practices and conventions within, across and among films. But we are not yet really dealing with the effects of these films on actual people – or at least actual people other than film fight choreographers.

To turn our attention to ‘real people’, we might refer back to our creation scenario one more time, and ask what happened to all of those impressionable and impressed boys and girls who left the cinema with a newly inculcated desire for this new ‘ancient’ thing called kung fu. As a range of commentators and historians have remarked, the scarcity and rarity of Chinese martial arts schools in Europe and the US forced people who desired to learn kung fu ‘like Bruce Lee’ to take up the much more readily available arts of judo and karate. There were comparatively more judo and karate clubs in Europe and the US than kung fu clubs. This disparity has geopolitical and historical causes that are too complex to cover adequately here. Suffice it to say that kung fu clubs gradually emerged in response to the demand. But the first big explosion in participation in Asian martial arts in the wake of the ‘kung fu craze’ was an uptake of judo, karate, and taekwondo, not kung fu. The films that inspired the interest came from Hong Kong, but the Asian martial arts on offer in the West came from Korea and Japan, generally via some connection to the military.

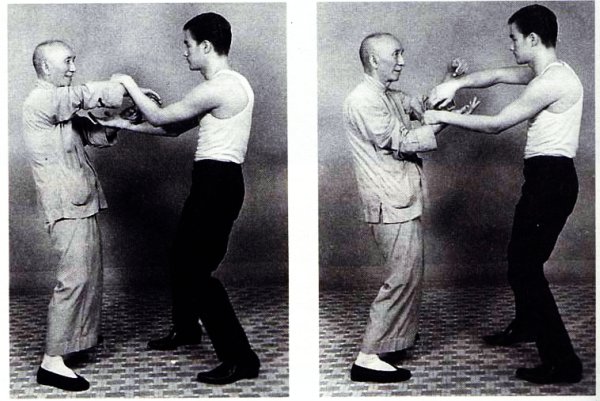

Over time, more was learned about Bruce Lee’s art. He had trained in wing chun kung fu as a teenager in Hong Kong. Wing chun is a close range fighting art with short punches, locks, grapples, and a preference for low kicks. When he moved to the USA at the age of 18, he was definitely a competent martial artist, and apparently blessed with incredible speed and grace of movement. His speed reputedly impressed even very senior and well established Chinese martial artists. Famously, however, his iconoclasm didn’t (Russo 2016).

Stories about and studies of Bruce Lee’s iconoclasm, irreverence and various fights and tussles abound. Rather than recounting them here, the point to be emphasised in this context is that when Bruce Lee gradually began to enter into the TV and movie business, first as a trainer, then choreographer, and supporting actor, he clearly knew that what mattered most on screen was drama. Hence, his screen fights always involved high kicks, jumps, and big movements. Everything was exaggerated and amplified (although those closest to him have claimed that he really struggled to move slow enough to enable the camera to capture his techniques).

Because of the complexity of this chiasmus, Bruce Lee can be said to have always sent his ‘followers’ moving in one of two or more directions. First, his Chinese kung fu sent people flocking into Japanese and Korean style dojos and dojangs. Second, Bruce Lee publicly disavowed formal stylistic training – first claiming to have abandoned wing chun, then naming his approach ‘jeet kune do’, then coming to regret giving it a name at all (Inosanto 1994; Tom 2005). Nonetheless, fans flocked to find wing chun classes. Others sought jeet kune do classes. Others took his message of ‘liberate yourself from styles’ or ‘escape from the classical mess’ to mean that one should reject any and all formal or systematic teaching and work out how to ‘honestly express yourself’, as Lee was fond of saying (Lee 1971).

Furthermore, within the jeet kune do community itself, a sharp divide appeared immediately after Lee’s death. Some of his students felt that they should continue to practice and teach exactly what Bruce Lee had practiced and taught with them. Others felt that the spirit of his jeet kune do was one of innovation, experimentation and constant transformation, and that what needed to be done, therefore, was to continue to innovate and experiment in line with certain principles or concepts. Hence a rift emerged among Lee’s closest friends and longest students. It continues to this day.

As such, all different kinds of people with all different kinds of orientation believed and continue to believe that they are ‘following’ Bruce Lee, that they love him and honour him and respect him. Yet they are all doing very different things and adhering to very different images and ideas. For all of them, Bruce Lee was ‘The Man’. I use this term because I have heard these words – and words like them – in many countries and contexts, from many different kinds of people, the world over.

The most memorable occasion was in Hong Kong, after a kung fu class. The style we were practicing was choy lee fut kung fu. This is very different to the wing chun kung fu that Bruce Lee studied as a teenager in Hong Kong, and a world away from the jeet kune do style that he devised as an adult in the USA. In fact, choy lee fut is often positioned as wing chun’s nemesis. It is certainly the style that is mentioned most frequently in the various versions of mythical stories of the young Bruce Lee in Hong Kong. In these stories we are told that wing chun students and choy lee fut students would often have formal style-versus-style duels on the city’s rooftops. Sometimes in these stories Bruce Lee is depicted as the scourge of all rivals. In other versions, an innocent young Bruce Lee is depicted as starting his first rooftop fight and immediately recoiling in pain and shock, before being told to get back into the fray, doing so, and emerging victorious.

In all of the Hong Kong based wing chun kung fu stories about Bruce Lee, choy lee fut kung fu comes off badly. Perhaps this is the reason for the frequent animosity that exists between wing chun and other styles of kung fu in Hong Kong. I certainly witnessed some of this during a visit there in 2010. The sense among practitioners of other styles of kung fu seemed to be that wing chun kung fu only became famous because of Bruce Lee’s fame. In this sense, the global success of wing chun itself could be regarded as a kind of cult formation that is indebted to Bruce Lee (Bowman 2010; Judkins and Nielson 2015). Certainly, I was also told in Hong Kong that among the ‘traditional’ Chinese martial arts community of Hong Kong, wing chun was regarded as simply too new and too local to deserve the global fame it had achieved in the wake of Bruce Lee.

Knowing this is doubtless what made my choy lee fut colleague’s declaration that ‘Bruce Lee was the man’ so significant for me. On the one hand, Bruce Lee popularised a rival style of kung fu, and stories about his martial arts encounters often involved the disparagement of other styles (specifically choy lee fut). But on the other hand, for all who had eyes to see, Bruce Lee was unequivocally brilliant – amazing to watch, astonishing, inspiring, graceful, powerful, elegant. So, even practitioners of ‘rival’ styles, even traditionalists who may disparage either or both wing chun and jeet kune do, could easily concede Bruce Lee’s brilliance and their admiration for him.

Of course, some may say that none of the examples of influence and importance that I have so far given really fall into the category of ‘cult’ as it is normally used, either conversationally, colloquially or as technically conceived within film studies. Neither children parroting and copying moves after a cinema visit, nor an expansion of martial arts classes as part of an international boom, nor the elevation of a once obscure southern style martial art constitute evidence of a ‘cult’ – certainly not one organised by devotion to a personality or a celebrity. Nonetheless, my claim is that all such examples are ripples that attest to a significant and generative intervention.

For, in the end, Bruce Lee most often functions as a kind of muse (Morris 2001). People have been inspired by Bruce Lee in myriad ways: musicians, athletes, artists, thinkers, performers, dancers, and others, have all referenced Bruce Lee as an inspiration. In the realms of martial arts practice and film fight choreography, Bruce Lee arguably dropped a bomb, the effects of which are still being felt. But, being forever absent, forever image, forever a few frozen quotations, what we see are a diverse plurality of practices of citation.

The different ways in which bits and pieces of ‘Bruce Lee’ are picked up and used (and abused) attest to the nature of his intervention. Before Bruce Lee, one could dream of being any number of things – footballer, athlete, rock star, and so on. After Bruce Lee, one more gleaming new option was definitively out of the box, on the table, in the air, everywhere: martial artist. This is why the impact and importance of Bruce Lee has always exceeded the world of film, and seeped into so many aspects of so many lives. This is another way in which Bruce Lee can be said to be like water.

Works Cited

Barrowman, Kyle. 2016. ‘No Way as Way: Towards a Poetics of Martial Arts Cinema’. JOMEC Journal 0 (5). https://publications.cardiffuniversitypress.org/index.php/JOMEC/article/view/282.

Baudrillard, Jean. 1994. Simulacra and Simulation. Body, in Theory. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Bazin, André. 1967. What Is Cinema? / [Vol. 1]. Berkeley: University of California Press.

BBC4. 2013. ‘Everybody Was Kung Fu Fighting: The Rise of Martial Arts in Britain, Series 12, Timeshift – BBC Four’. BBC4. February 24. http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b01p2pm6/clips.

Bleecker, Tom. 1999. Unsettled Matters: The Life and Death of Bruce Lee. Lompoc, Calif: Paul H. Crompton Ltd.

Bowman, Paul. 2010. Theorizing Bruce Lee: Film-Fantasy-Fighting-Philosophy. Rodopi.

———. 2013. Beyond Bruce Lee: Chasing the Dragon through Film, Philosophy, and Popular Culture. Columbia University Press.

Brown, Bill. 1997. ‘Global Bodies/Postnationalities: Charles Johnson’s Consumer Culture’. Representations, no. No. 58, Spring: 24–48.

Chan, Jachinson W. 2000. ‘Bruce Lee’s Fictional Models of Masculinity’. Men and Masculinities 2 (4): 371–87. doi:10.1177/1097184X00002004001.

Chong, Sylvia Shin Huey. 2012. The Oriental Obscene: Violence and Racial Fantasies in the Vietnam Era. Durham: Duke University Press.

Chow, Rey. 2007. Sentimental Fabulations, Contemporary Chinese Films: Attachment in the Age of Global Visibility. Film and Culture Series. New York: Columbia University Press. http://www.loc.gov/catdir/toc/ecip075/2006039237.html.

Derrida, Jacques. 1976. Of Grammatology. Translated by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Baltimore ; London: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Foucault, Michel. 1991. The Foucault Reader. Penguin reprint. Penguin Social Sciences. London: Penguin Books.

Hall, Stuart. 1992. ‘Cultural Studies and Its Theoretical Legacies’. In Cultural Studies, edited by Cary Nelson and Paula Treichler Lawrence Grossberg, 277–94. New York and London: Routledge.

Hiramoto, Mie. 2012. ‘Don’t Think, Feel: Mediatization of Chinese Masculinities through Martial Arts Films’. Language & Communication 32 (4): 386–99. doi:10.1016/j.langcom.2012.08.005.

Hunt, Leon. 2003. Kung Fu Cult Masters: From Bruce Lee to Crouching Tiger. London: Wallflower.

Inosanto, Dan. 1994. Jeet Kune Do: The Art and Philosophy of Bruce Lee. London: Altantic Books.

Judkins, Benjamin N., and Jon Nielson. 2015. The Creation of Wing Chun: A Social History of the Southern Chinese Martial Arts. SUNY Press.

Kato, T.M. 2007. From Kung Fu to Hip Hop: Revolution, Globalization and Popular Culture. New York: SUNY.

Lee, Bruce. 1971. ‘Liberate Yourself from Classical Karate’. Black Belt Magazine.

Lo, Kwai-Cheung. 2005. Chinese Face/Off: The Transnational Popular Culture of Hong Kong. University of Illinois Press.

Marchetti, Gina. 1994. Romance and the ‘Yellow Peril’: Race, Sex, and Discursive Strategies in Hollywood Fiction. University of California Press.

———. 2001. ‘Jackie Chan and the Black Connection’. In Keyframes: Popular Cinema and Cultural Studies, edited by Matthew and Villarejo, Amy Tinkcom. London: Routledge.

———. 2006. From Tian’anmen to Times Square: Transnational China and the Chinese Diaspora on Global Screens, 1989-1997. Temple University Press.

———. 2012. The Chinese Diaspora on American Screens: Race, Sex, and Cinema. Temple University Press.

Mathijs, Ernest. 2005. ‘Bad Reputations: The Reception of “Trash” Cinema’. Screen 46 (4): 451–72. doi:10.1093/screen/46.4.451.

Mathijs, Ernest, and Xavier Mendik. 2008. The Cult Film Reader. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

McCormack, Pete. 2012. I Am Bruce Lee. Documentary, Biography.

Miller, Davis. 2000. The Tao of Bruce Lee. London: Vintage.

Morris, Meaghan. 2001. ‘Learning from Bruce Lee’. In Keyframes: Popular Cinema and Cultural Studies, edited by Matthew and Villarejo, Amy Tinkcom, 171–84. London: Routledge.

Nitta, Keiko. 2010. ‘An Equivocal Space for the Protestant Ethnic: US Popular Culture and Martial Arts Fantasia’. Social Semiotics 20 (4): 377–92. doi:10.1080/10350330.2010.494392.

Prashad, Vijay. 2002. Everybody Was Kung Fu Fighting: Afro-Asian Connections and the Myth of Cultural Purity. Beacon Press.

———. 2003. ‘Bruce Lee and the Anti-Imperialism of Kung Fu: A Polycultural Adventure’. Positions 11 (1): 51–90. doi:10.1215/10679847-11-1-51.

Preston, Brian. 2007. Bruce Lee and Me : Adventures in Martial Arts. London: Atlantic.

Russo, Charles. 2016. Striking Distance: Bruce Lee and the Dawn of Martial Arts in America. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Shepard, Bret. 2014. ‘Cult Cinema by Ernest Mathijs and Jamie Sexton. Walden, MA and Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011’. Quarterly Review of Film and Video 31 (1): 93–97. doi:10.1080/10509208.2011.646214.

Teo, Stephen. 2009. Chinese Martial Arts Cinema: The Wuxia Tradition. Edinburgh University Press.

———. 2013. The Asian Cinema Experience: Styles, Spaces, Theory. Routledge.

Tom, Teri. 2005. The Straight Lead: The Core of Bruce Lee’s Jun Fan Jeet Kune Do. North Clarendon, VT: Tuttle Publishing.

Webb, Steve. 2009. How Bruce Lee Changed the World. Documentary. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1437833/.

[i] I have been told this numerous times by editors of martial arts magazines and bloggers, both UK, US, and transnational/online.

[ii] I discuss the ways in which the term ‘Bruce Lee’ organises a complex field of images, ideas, citations and allusions in Beyond Bruce Lee (Bowman 2013).

July 20, 2017 at 11:11 am

In the Berton interview at one point BL demonstrates JI. The Wiki bio states that he trained a bit in Wu-style TCC. Is there any firm information about this? I know in Toronto some senior Wing Chun and Wu stylists associate.

Thanks!

July 20, 2017 at 11:19 am

Hi father was a long time Taijiquan practitioner. That is where all of the discussions of BL and Taiji seem to start. But Wing Chun was the only art that he “formally” studied.