An all too Common Conversation

Last week my Sifu and I were discussing the public conversation that surrounds Wing Chun.

“So this guy was trying to tell me that we have no head movement in Wing Chun. Not just bobbing and weaving” he clarified “but that we can literally never move our heads.”

“So he thinks we stand there and get punched in the face?” I asked incredulously.

“Pretty much. I told him to take a closer look at the forms.”

Such exchanges are not all that uncommon. Normally I try to ignore them. However, in the last few months I have had a number of almost identical conversations with talented, highly experienced, Sifus all relating practically identical incidents.

Not all of these discussions focused on head movement. In one case an instructor was approached by an individual (who apparently was not a Wing Chun student) claiming that our system contained only a single punch. This is a rather odd assertion to make about a fighting system that prides itself on a rich and deep bench of boxing techniques.

I have actually heard a similar claim made before by some practitioners attempting to make a philosophical point. They note that the basic Wing Chun punch reflects a set of core principles that, when applied in different situations, can yield a variety of techniques that superficially look quite different, but all reflect a common approach to hand combat. This is sometimes couched in quasi-Taoist terms as “the one thing giving rise to the ten thousands.” I immediately asked whether this is where my friend’s interlocutor may have been headed.

“Nope. He literally believed that we only have a center-line chain punch. Anything else, an outside line, an uppercut or hook, ‘cannot be Wing Chun’.” The instructor absentmindedly went through movements from the second and third unarmed boxing form as he clarified the objection.

“So what did you tell him?” I asked.

“I just kept telling him to go back and look at the forms. Youtube is full of people doing all sorts of forms. For Christ sake, just pick anyone of them.”

“Sending someone to Youtube can be a trap for the unwary.” I offered.

“Yeah, I sent him some links. But I have no idea if it did any good!”

Perhaps the most interesting thing about such challenges is that they do not all arise from outside of the system. Earlier this summer I had a conversation with a third Sifu that was more serious in nature. When another instructor (from the same Wing Chun umbrella organization) visited his school, he was aghast to discover that my friend was having his students practice entry drills (or more specifically, techniques that allow one to transition from disengaged, to kicking to boxing ranges as safely as possible). Nor was he happy to discover that my friend’s more advanced students were starting Chi Sao (a type of sensitive training game) from unbridged positions. “This is not Traditional Wing Chun!” he objected.

That was certainly news to me. The system contains entry techniques. Why not drill them? Why not create a greater sense of complexity and realism by adding them (or joint locks, or kicks) to your Chi Sao? My personal training happened in a school built on a “traditional lineages” going back to Ip Man. We certainly practiced both of these things, nor was it ever considered to be the least bit controversial. Apparently not all lineages share this same approach to training. The uproar that resulted from the visit caused my friend to remove his school from an organization that he had been part of for some time.

Who wants their martial practice to be defined only by the things that one (supposedly) does not do?

This is something all Wing Chun students deal with from time to time. My personal favorite is when people tell me that Wing Chun is an exclusively short range art with highly restricted footwork. All this tells me is that the individual in question has never seriously studied the swords and has no idea how much distance that footwork can actually cover. Let’s just say that there is a very good reason why Bruce Lee turned to fencing in his attempt to augment his own incomplete training in Wing Chun. Nor would I call a 3-4 meter pole a “short range” weapon. Wing chun is clearly a short range art…except when it is not.

In reality every self-defense art strives to be a complete system of combat. Granted, all approaches will have their unique strengths and weaknesses, but real martial artists work very hard to present as strong a front as possible. No one who wants to defend themselves refuses to train kicks, throws or weapons simply because “everyone knows that Wing Chun is a short range boxing art.”

Fighting Strength with Strength

I have never been one for social media debates over statements like this. There is always too much to read, and time spent arguing about Wing Chun gets in the way of actually doing it.

Recently I came across something in my research that made me start to wonder if perhaps I should think a little more deeply about these conversations. The Wing Chun community is not the only martial art in which such debates occur. Why do people try so hard to impose negative definitions on a community of practice, even if it means ignoring techniques that are clearly present in the orthodox forms? How can we understand the social purpose of these debates? What sorts of work are they doing in the martial arts community today?

Unsurprisingly Japanese martial artists were among the first to explain their practice to the wider global community. Rather than allowing systems like Kendo, Jujitsu or Judo to be framed and discussed in English exclusively by foreign reporters and visitors, reformers from within the Japanese martial arts community went out of their way to describe, and even promote, their practices on their own terms. They frequently discussed their arts as extensions of fundamental Japanese values. In so doing they entered directly into the ongoing debate as to what the values of the Japanese people actually were, what vision of Japanese modernity should emerge, and what role traditional “physical culture” should play in promoting and cementing these identities.

Kanō Jigorō, internationalist, educator and the creator of Judo was often at the center of these discussions. Other young, educated, members of the Kodokan also took up his mission of the spreading the gospel of Judo. On April 18th of 1888 he and Rev. T. Lindsay presented a paper titled “Jiujitsu: The Old Samurai Art of Fighting Without Weapons” at the British Embassy in Japan. The paper sought to introduce Kanō’s recently created martial art to the English speaking world while at the same time situating it firmly within the bounds of Japanese martial history and nationalism. Given the timing, subject matter and location of the talk, one would be hard pressed to see this as anything other than an early example of the martial arts entering the realm of cultural and public diplomacy.

Nor would this be the last that the English speaking world would hear on the subject. A stream of newspaper and magazine articles would bring Judo to the forefront of Western popular culture following Japan’s victory over Russia in 1905. Yet even before that the West’s fascination with Japanese culture, and its admiration for its rapid reforms, ensured a fair amount of attention.

Shidachi’s 1892 paper, “Ju-Jitsu: The Ancient Art of Self-Defence by Slight of Body,” in some ways is even more interesting than Kanō’s earlier piece. Its importance in no way derives from its originality. Shidachi, a Judo enthusiast, was serving as the Secretary of the Bank of Japan when he delivered his paper at the Japan Society in London. At times he followed Kanō’s original presentation so closely that one suspected he might have been editorializing on the previous article. From the perspective of our current discussion, the most interesting aspect of Shidachi’s paper was the response that it provoked from well-placed members of the area’s “sporting community” (boxers and wrestlers).

Like Kanō, Shidachi spent a great deal of time framing the newly created (or reformed) practice of Judo as a continuation of Japan’s unique history and “national heritage.” It should be remembered that while still important today, such conversations were especially loaded during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This was the great era of awakening in which the discovery (or construction) of national identities was in full swing. Bodies of folk culture were ransacked by intellectual entrepreneurs hoping to support claims of national legitimacy, and to win the global respect that came with it. Of course such elements could only be seen as evidence of a “primeval national community” if they were ancient and unique.

Naturally this led the early exponents of Judo to spend a lot of time defining their practice by clarifying what it was not. To begin with, both Kanō and Shidachi knew that there were many lineage myths tracing certain Japanese martial practices back to China. Modern students of martial arts studies now acknowledge that there was a fair amount of martial exchange between these two states at certain points in time. For instance, Knutsen and Knutsen (2004) have discussed the many Samurai who traveled to China during the Ming dynasty specifically to study Chinese spear and pole fighting techniques. Further, it is clear that 19th century Fujianese Kung Fu had a notable effect on the development of Okinawan Karate.

Given China’s late 19th century reputation as being a hopeless backwards “failed state” (to use modern political terminology), the last thing that Japanese nationalists wanted was to be in any way associated with “Chinese Boxing.” And so both authors went to lengths to argue that Chinese boxing practices (focused as they were on hitting and kicking) had no part in the development of Japan’s “pure” jujitsu. Such techniques were never part of Japanese unarmed combat, even if the lineage histories of some clans suggested otherwise.

This move was only the first step in a more complex balancing act. While Shidachi sought to distance his martial practice from Chinese Boxing, he did not want his audience to go on and draw the natural conclusion that what he was describing (and demonstrating) was more similar to Western wrestling.

Once again, Shidachi turned to negative arguments. Judo, he informed his audience, is different from wrestling because it does not employ strength. Rather, it is a character building exercise. Beyond that, technique and practice were the keys to victory. Judo was not about trying to “overpower” your opponent, as was the case in wrestling. He concluded his talk with a brief demonstration designed, by all accounts, to illustrate why he characterized his practice as “slight of body.”

Shortly thereafter a review of Shidachi’s talk ran in the local press. The Japan Society did modern students of martial arts studies the great favor of printing the ensuing debate at the end of the original talk in their proceedings. It seems that not all members of the local sporting community were impressed by what Shidachi had said or his subsequent demonstrations.

Certain allowances were made for the fact that Shidachi was by no means a professional wrestler and he had only a hapless (and improperly dressed) volunteer to work with. It was candidly admitted that one could only expect so much from his demonstration.

Yet critics also objected that very little of what they saw or heard was actually new. One could already find much sturdier Jujitsu practitioners in the city’s fledgling Japanese community. Shidachi’s reply to this claim more or less boiled down to an assertion that since these individuals were not Kodokan trained, whatever it was they were doing could not be considered “authentic.” Some types of martial debates, it seems, are eternal.

The author of the review also took offense to the off-handed, yet frequently repeated, assertion that Western wrestling was an amoral endeavor in which victory was achieved by pitting brute strength against brute strength. Such characterizations of Western boxing and wrestling were common in both China and Japan where martial arts reformers sought to locate the essence of certain foreign sports in an essentialist vision of national identity. The West had triumphed in the realm of economic, military and scientific might, and that truth must be reflected in its modes of athletics and combat.

Early reformers in martial arts like Taijiquan (Wile 1996) and Jujitsu sought to shore up their own national identities by asserting that they brought a unique form of power to the table. Rather than relying on strength, they would find victory through flexibility, technique, and cunning (all yin traits), just as the Chinese and Japanese nations would ultimately prevail through these same characteristics. It is no accident that so much of the early Asian martial arts material featured images of women, or small Asian men, overcoming much larger Western opponents with the aid of mysterious “oriental” arts. These gendered characterizations of hand combat systems were fundamentally tied to larger narratives of national competition and resistance (see Wendy Rouse’s 2015 article “Jiu-Jitsuing Uncle Sam” .

The problem with repeating myths like these is that, if one is not careful, you actually start to believe them. Or in more theoretical terms, they come to structure one’s understanding of both practice and its place in the larger world.

Shidachi’s repeated assertions not withstanding, few Western wrestlers understood their practice as an amoral exercise in brute strength. Both the UK and the US have long had their own discourses as to how sports like wrestling and boxing function as a type of “moral education” for young men. Promoting these discourses in the 19th and early 20th centuries was an important step in winning society’s tolerance for such activities (and their legalization). One suspects that Chinese and Japanese arguments about the ethical benefits of their martial arts were accepted so readily in the West because they were a continuation of what was already believed about the social value of wrestling, and to a certain extent boxing.

Shidachi appears to have had little actual familiarity with Western wrestling. It is clear that his discussion was driven by nationalist considerations rather than detailed ethnographic observation. And there is something else that is a bit odd about all of this. While technical skill is certainly an aspect of Western wrestling, gaining physical strength and endurance is also a critical component of Judo training. Shidachi attempted to define all of this as not being a part of Judo. Yet a visit to the local university Judo team will reveal a group of very strong, well developed, athletes. Nor is that a recent development. I was recently looking at some photos of Judo players in the Japanese Navy at the start of WWII and any one those guys could have passed as a modern weight lifter. One suspects that the Japanese Navy noticed this as well.

These inconsistencies only got worse when the conversation turned to the realm of actual technique. In an attempt to show how one might deal with an opponent without resorting to the use of strength Shidachi demonstrated a certain technique before the assembled gentlemen of the Japan Society. Yet the wrestlers in the room immediately realized that this supposed hallmark of the Japanese national character was also a part of their (very English) daily tool kit. Nor, in their view, was it nearly as clever or as well executed as Shidachi seemed to think.

On a fundamental level Japanese and British wrestlers had more in common than either side might be eager to admit. Or to put it slightly differently, the obvious differences between Western wrestling and Japanese judo stemmed from a number of sources that had little to do with the myths of “national essence” being promoted by Shidachi.

For his part Shidachi had no good response when confronted with the many similarities that his audience perceived. In the modern age there is no more fundamental type of identity than nationalism. Like all identities it structures how we perceive the world and the evidence that we are willing to accept. To point out that a number of Judo techniques also appear in other styles of wrestling was taken (and possibly meant) as a direct affront to the legitimacy of Japan’s unique identity.

Instead of engaging with Western wrestlers on their own terms (and in a way that reflected their own values and understanding of wrestling) Shidachi simply retreated back into his talking points. Everyone knew that Japan and England were different; therefore their philosophies of wrestling must be fundamentally unique as well. Any perceived similarity could only be a misperception born of ignorance of Judo’s deeper aspects. The Japanese student had no need of strength, and the Western wrestler (all protests to the contrary) must rely on nothing else. Only in that way could the identity of both communities be preserved.

Technique as Community, Practice as Research

This incident, culled from the first years of the engagement between Asian and Western martial artists, sheds light on why so many modern students feel compelled to define Wing Chun by what it does not do. Notice again that almost all of these discussions revolve around the question of technique.

By technique I mean the aspect of martial practice that can be conveyed between generations and taught to students. Technique can deal with basic movement and body mechanics or specific applications. It can be transmitted through rote repetition or reinforced with a conceptual framework. In any case, technique is the embodied aspect of a martial practice that endures. Whereas individual applications or reaction to acts of violence may be brilliant, they are always singular events, confined to a specific moment in time. Technique, however, has the possibility of transcending any individual moment (Spatz 2015).

It is this ability to endure through the generations that makes bodies of technique so important within the traditional martial arts. As I have argued elsewhere, at their heart the martial arts are essentially social institutions. One cannot understand their origins, social function or individual meaning if you divorce them from the larger cultural, economic, legal, philosophical or aesthetic institutions that tolerate and reinforce them. That is one of the reasons why interdisciplinary approaches to martial arts studies have such great utility.

Society allows the martial arts to exist because they do work that is collective usefully. Individuals support these institutions because they desire the social and personal transformation that they promise. Yet none of these goals can be accomplished if the hand combat community does not first find a way to spread and perpetuate its identity through space and time.

A shared body of technique represents the physical embodiment of a new collective identity. As I have argued in previous papers, the martial arts can be understood as liminal structures that seek to transform their members through an extended initiatory experience. Learning new techniques is almost always at the heart of this progression. It is the mastery of technique that is put to the test in public spectacles designed to confirm one’s advancement in the system. Nor can one go on to teach new members of the group without having first mastered this shared body of technique. Both those inside and outside the community are likely to identify your place within the larger martial world by the range of techniques that you can display.

Within this context to cease to practice (or even forget) certain techniques is not simply matter of expediency. One may be seen as literally walking away from a community based on shared collective practices. Likewise, to add new elements to one’s training (such as entry drills) can be taken as an affront to the group’s identity. One cannot simply dismiss this reaction as all martial arts are first and foremost social institutions.

Yet there is another aspect of practice that must be considered. Here I draw freely from Ben Spatz’s volume, What a Body Can Do: Technique as Knowledge, Practice as Research (Routledge 2015). While there is an undeniably social aspect to the formation and transmission of technique, practice also generates types of knowledge that resides within an individual body. Further, individual practice structures and augments the body in ways that are sometimes predictable (one learns Wing Chun precisely because you wish to punch faster), and sometimes radically unexpected (after five years of Wing Chun practice you find yourself becoming ambidextrous, even though that was never a stated conceptual aim of the system).

Spinoza’s question “What can a body do?” has no simple answer. What your body can do today is largely a matter of what techniques you learned in the past. Further, as you delve more deeply into the details of a given practice you are likely to find previously undiscovered depths and insights. Thus the practice of Wing Chun inevitably shades into more basic research on Wing Chun’s techniques. As any University professor can tell you, basic theoretical research inevitably leads to innovation in practice. Innovation is a not a bug in this system, rather it is an essential feature of any pedagogical system based on the practice of bodies of techniques (the protests of Confucian traditionalists not withstanding).

Innovation within the realm of the martial arts is inevitable for another reason as well. Students of self-defense arts like Wing Chun (or Judo for that matter) are not simply practicing their techniques in a vacuum. Whether in training or actual combat, they are expected to deploy them against a partner who will react in strategic, innovative and adversarial ways. Such training forces one to accelerate the process of personal research when it happens in a classroom. One can only imagine the impact of Ip Man gleefully goading his young students into starting actual street fights to test their techniques.

Of course what was effective in Hong Kong in 1953 was probably pretty different from what Leung Jan was contemplating in Foshan in 1853, as gentry led militias fought their way through the burning streets of Foshan employing muskets, hudiedao and long spears. Both the internalized process of individual research as well as the need to react strategically to an evolving threat environment ensures that martial arts will change, sometimes in radical ways, over time.

The debates that opened this essay will not disappear anytime soon. They reflect a dialect process that has been present since the first years of the West’s engagement with the Asian martial arts. Nor will they be resolved by referencing Youtube’s ever growing archive of martial practice.

These fighting systems, and their pedagogical strategies, are fundamentally social in nature. Potential students are attracted by the promise of community and a deep personal need for transformation. All of that implies boundary maintenance. A closed canon of techniques makes this identity real at an embodied level. Through practice one’s membership in the community can literally be felt and enacted on a daily basis. Breaking with that may elicit strong emotions, including feelings of betrayal.

On the other hand, one cannot practice technique without engaging in research. This is how a student makes a martial art their own. It is what allows them to respond, in rational ways, to an evolving threat environment. And the martial arts must continue to change.

While they are quite good at promoting the illusion of eternal continuity, the truth is that they have changed in every previous generation, sometimes in radical ways. It would be a mistake to assume that our generation alone is exempt from this responsibility. Perhaps the most generous way to understand the debates about what Wing Chun is missing is as a popular expression of the need to balance these fundamental, yet competing, aspects of practice. As technique travels through time it enables the renegotiation and movement of identity. Only through this process can we understand what Wing Chun is, and what it is becoming.

oOo

If you enjoyed this essay you might also want to see: The “Wing Chun Rules of Conduct”: Rediscovering Ip Man’s Original Statement on the Philosophy of the Martial Arts.

oOo

February 3, 2017 at 10:12 am

I’ve been reading this journal for a while now, and this is my favorite editorial so far. I really appreciate this critical look at how traditional arts have evolved, have been perceived to have evolved, and how they potentially can evolve. It becomes tiresome listening to some of the traditional dogma on the one hand, and the impudent chop suey approach of the modern MMA myth.

February 3, 2017 at 11:13 pm

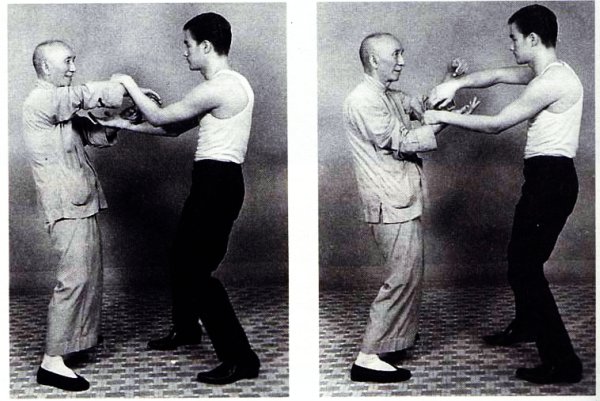

I would like to thank Joseph Svinth for passing me a link to the second photo in this post, which fits the text perfectly. Anyone who found this post to be interesting may also want to check out this other source which he suggested. Check it out for a similar discussion on this side of the pond!

“American Wrestling vs. Jujitsu” (2002) Journal of Combative Sports

http://ejmas.com/jcs/jcsart_leonard_0802.htm

Cosmopolitan, Volume 38 (1905)

https://books.google.com/books?id=wqg_AQAAMAAJ&lpg=PA40&ots=-Aw2CJqetp&dq=leonard%20higashi%20wrestling%20v%20judo&pg=PA40#v=onepage&q=leonard%20higashi%20wrestling%20v%20judo&f=false

February 22, 2017 at 6:19 pm

Nice post on ‘Missing’. I have enjoyed your posts for quite some time and I’d like to add that the scope of THIS particular subject could be broadened much further to include the ‘internal’ lineage disputes, including but not limited to.. “OUR Wing Chun lineage is Better because it’s the ‘Complete’ system”. Most of these practitioners don’t understand what they are saying. Why? Because they don’t know what they don’t know. Huh? What I mean is, if one doesn’t know something exists, how can they tell if it’s.. ‘missing’?

Wing Chun is THE most abused system out there, mainly because of Short-Change Sifu’s. A SiFu either taught by someone who believed ‘they’ learned the complete system by training two or three times a week, 2 hrs. a night, for 3 years, and opened up a kwoon. OR worse, someone who quit after a couple years and for pride and/or money, became a sifu. [An example of the later is a guy who lives in PSL, Florida, literally passing himself off as a ‘Master’ of WC.. yet he was never taught beyond learning the Jong form. Not even its applications.

Today, most are aware of 3 hand sets, wooden man, pole, knives.. however, back then, this was NOT what Ip taught to the vast majority of his students. A student who was around for a few years learned the first two hand forms, chi-sau, and wooden man. There’s a bit more to it, but if one was dedicated, a fighter, and around a few years, then he taught the pole, limited knife and no advanced footwork.

It’s hard to believe that today. That’s because of sites like Youtube, and ALL lineages have access to it. Reality is, Ip only taught a handful of students the 3rd form, advanced knives (with separate jong), and only a couple were taught advanced footwork with their separate jong’s.. the tripodals and moifa. [plumb blossom]

Therefore, as a barometer, if you, the reader, really are learning the ‘Complete’ system, it will contain the later. But wait.. that being said, today, with Youtube, some of those lacking lineages [which would be most] have used it to watch and have devised and inserted their own versions of what was lacking. My humble advice, if you WANT to learn the complete system, realize it will take 20+ years to do. If YOUR Sifu’s teaching ends after 5 years, it isn’t complete, so do some research [the author of this article is a Great start], because, if one doesn’t know something exists, how can they tell if its missing?

October 9, 2017 at 11:16 am

“Of course what was effective in Hong Kong in 1953 was probably pretty different from what Leung Jan was contemplating in Foshan in 1853, as gentry led militias fought their way through the burning streets of Foshan employing muskets, hudiedao and long spears.”

Would it be possible that Wing Chun’s origin (weaponry at least) might come from the gentry’s formulation of military techniques to teach their militia? Like your blog mentioned before..the spear and hudiedao was the two most popular weapons for the militia in Guangdong. WC was also known as “Siu Yeh Kuen” (“Young Master’s Fist”). Of course the style also survived in other parts of the region (Gulao village from Leung Jan, etc.) among the peasantry. But the fact that it was usually being passed down closed-door among the relatively well-off families (Leung Jan, Chan Wah-Shun, and Yip Man) and everyone before them is obscure makes this quite probable I think or at least for where the weapons influence came from.