Charles Russo. 2016. Striking Distance: Bruce Lee & the Dawn of Martial Arts in America. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. 264 pages. $24.95 USD (Hardcover)

Anyone can tell you that it is easier to review a good book than a bad one. This simple truth makes Charles Russo’s latest volume a pleasure to discuss. Striking Distance: Bruce Lee & the Dawn of Martial Arts in America (Nebraska UP, 2016) is one of those rare martial arts volumes that is likely to be widely read by individuals practicing a variety of styles. It will also be of interest to those who are looking for a better vantage point from which to observe the history of the San Francisco Chinese community at a time of immense social change but have no background in the fighting arts.

Still, it is among martial artists that this book will have its greatest impact. I fully expect that it will be discussed for years to come. It may even play a similar role to R. W. Smith’s classic Chinese Boxing: Master and Methods (Kodansha, 1974) for a new generation of martial artists seeking to better understand their roots.

The comparison with Smith is an interesting one. The first thing that readers will notice is the quality of Russo’s writing. Simply put, this is a wonderfully written book. Its style is at turns lyrical yet succinct. Russo’s descriptions of individual events are rich and evoke a sense of texture and place that I have not encountered in very many descriptions of martial arts history.

His ability to reproduce a sense of intimacy, from smoked filled halls to creaky staircases, give his narrative a gripping quality. This is amplified by the use of short chapters, each of which flows easily into the next. The end result is a genuinely compelling story.

Smith was also an engaging writer. While an intelligence officer by trade his writing reflected the journalism of his day. His brief yet incisive descriptions of the martial artists that he encountered drew in many readers and earned him a great many fans. I suspect that Russo’s text will be received in much the same way.

Nevertheless, it is the contrasts that I find most interesting. Smith was a deeply devoted martial artists. Like many young men of his generation he had come up through the ranks of boxing and judo before moving on to the newer and more exotic fighting systems (karate, taijiquan, kali and the various schools of kung fu) that would erupt into the public consciousness during the 1970s.

R. W. Smith was an early adopter of the Chinese fighting arts and he eagerly sought to promote these in the West. He hoped to not just to document what he saw, but to shape public opinion about these subjects through his writing. While this gave his prose a bite that many readers found enjoyable, it also led him to make some assertions that now require reevaluation.

In comparison Russo has little skin in the game. He does not identify as a martial artist and has none of the personal or stylistic loyalties that dominate the work of his literary predecessor. Russo is a professional Bay Area journalist and writer with a keen interest in local history and a nose for a good story. The San Francisco martial arts scene, from the 1940s through the 1960s, provided ample material to satisfy both of these instincts.

It is even possible that Russo’s status as a non-practitioner was an advantage while researching this volume. As quickly becomes apparent, this work is not based so much on the sorts of historical research that one does in a library (though there is some of that) but on literally hundreds of interviews and casual conversations with individuals who were direct observers of the events in question. A certain “neutrality” on the question of local loyalties was probably beneficial in winning the trust of his various sources.

And like any good journalist Russo has spent a good deal of time cross-checking these verbal accounts and comparing them to previously published sources. When particularly complex issues arise serious thought is given to the credibility of the different perspectives that exist within the community.

The end result is a nuanced view of individuals like Lau Bun, Wally Jay, Ed Parker and Bruce Lee that steadfastly resists the temptation to romanticize them. Russo seems to understand that it is the “warts” that humanize us, which make empathy possible in a “warts and all” history. In this way he avoids the rhetorical extremes of his predecessor.

Yet this is more than the story of a handful of people. It is also the story of a place. San Francisco’s Chinatown stands out as a key actor in these events, exerting a type of influence on the unfolding story. Russo’s history provides critical insights into not just the martial arts, but the neighborhood that supported them.

In my own study of Wing Chun in Foshan and Hong Kong I called for a greater emphasis on local and regional history within martial arts studies. When we focus on only systemic and national level trends we create a distorted image of how the martial arts were actually experienced by most of their practitioners. Why did individuals turn to them? How were they able to express their own desires for the future through these practices?

Russo’s work stand as a powerful testament to the value of a local, layered, perspective in answering these key questions. One can only hope that this volume inspires future studies tackling different cities, time periods and communities.

Readers interested in Bruce Lee’s life and development as a martial artist will find much value in this volume. As one of San Francisco’s most famous sons (and martial artists) Lee’s exploits bookend Russo’s narrative. His narrative begins with Lee’s appearance at one of Wally Jay’s locally famous luals and it ends with his now (in)famous showdown with Wong Jack Man at his Oakland school. In between we are introduced to the key figures and personalities that shaped the Bay Area Chinese martial arts scene through the middle of the 1960s.

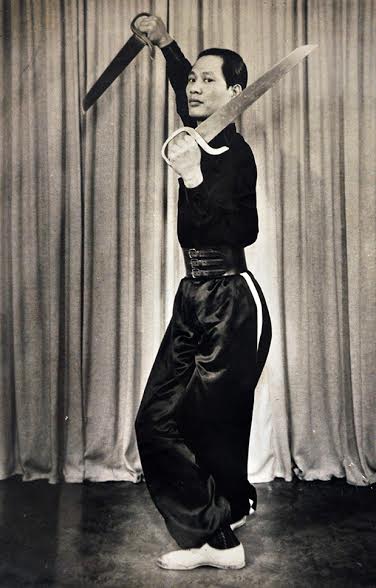

Special attention is paid to Lau Bun (the description of his school is really wonderful), T. Y. Wong (another Chinatown institution) and the Gee Yau Seah club (“Soft Arts Academy”) as the three forces that shaped the area’s small but stable martial arts scene from the start of WWII through the middle of the 1960s. After that a series of complex social changes in the neighborhood unleashed a reorganization of the area’s hand combat community.

Russo’s project is to excavate the region’s martial arts as they existed prior to the burst of growth and creativity that gripped the area in the late 1960s and 1970s. This older stratum of social history has always been harder to pin down, and as such he has done valuable work in reconstructing both how the area’s martial arts culture initially evolved, and why a modernist counter-movement eventually began to coalesce in Oakland (a group with which Bruce Lee found a natural home). Yet it is the accounts of pioneers such as Lau Bun and T. Y. Wong (as well as Ed Parker and Wally Jay) that more historically minded readers will be drawn to.

If I have one serious complaint about this book it would have to be the length. At about 150 pages of actual text I found it to be too short by half. Given the engaging nature of Russo’s prose I suspect that most readers will be left wanting more. Yet that desire is also telling.

When evaluating a work such as this we must ask ourselves whether it is capable of not only answering questions but also inspiring new ones. I suspect that the answer is yes.

Russo has approached this work as a journalist, and not as an academic student of martial arts studies. As such he is more concerned with reporting his narrative than asking questions about the causality or social meaning of the events that he relates. Yet many of his stories might be the jumping off point for further discussions.

One issue that arises repeatedly throughout his text is the supposed teaching ban on non-Chinese students within the traditional Chinese martial arts. I say “supposed” as while many individuals assert that such a ban was in place, it is not actually clear how many non-Chinese students were petitioning for instruction in San Francisco during the 1940s or 1950s. Prior to the 1940s there does not appear to have been much in the way of public schools for anyone to study at. And by the time that Russo’s narrative really gets going there is a small but steady stream of non-Chinese students that appear throughout the period in seeming defiance of such a ban.

So what was the nature and purpose of this ban, and why did it collapse so quickly after the first few years of the 1960s? In what ways was this norm expressed differently within the Bay Area Chinese community (because of its direct experience of neighborhood level racial hostility) than in the taijiquan community back in China?

With regards to these questions it seems that Russo’s sources provide him with somewhat contradictory accounts, the implications of which are not always clear. On one level this presents future researchers with a simple empirical problem. Did Ip Man really kick Bruce Lee out of his school because of his mixed race heritage? Can this actually be documented by period accounts?

Yet the theoretical implications of this conversation are even more important. How was it that shared narratives of community exclusion, then inclusion, shaped Chinese American identity in the 20th century, regardless of what any specific teacher actually chose to do in the face of this norm? How was this different from, or connected to, the parallel process that was unfolding in Hong Kong, or Taiwan?

At times I expect that Russo’s reliance on interviews and eye-witness accounts has probably led him astray. If we have learned anything from the field of law it is that human memory is a highly fungible thing, especially when decades have been allowed to intervene. When Ip Man entered Hong Kong late in 1949 his wife back in Foshan was very much alive. He was not a widower. Yet that is not how he is always remembered now. Russo directly tackles the problem of “motivated memory,” both at the individual and community level, when discussing the aftermath of the Wong Jack Man fight at the end of his study.

Still, anthropologists and ethnographers would be quick to remind us that the “remembered events” that did not really happen are just as critical to understanding the nature and texture of a community as those that did. If we treat this work only as a simple history of Bruce Lee we might be disappointed by contradictory accounts or historical “mistakes”. Yet there are already other sources that we can turn to for most of that information. Such a reading is in danger of missing the point of a work like this.

What Russo has presented us with is the history of a place caught at a critical moment of transformation. It has often been assumed that the earlier character of this neighborhood is forever lost and that its influence on the shape of the American martial arts has been limited. After all, Lau Bun and T. Y. Wong are hardly household names within the American martial arts community, despite their notable careers.

This short book makes the opposite argument. It demonstrates that their history is still a living, breathing thing. It is a force that is being remembered and retold. It is valued by the community that bears it and elements of it have become part of local identity.

Lastly, the history of the Bay Area during this critical decade has shaped the subsequent evolution of the martial arts in America in many ways. Some of them were profound, others are easily overlooked. This the ultimate message of Russo’s book. It reminds us that, if understood correctly, local history has a way of becoming all of our histories.

oOo

If you enjoyed this review you might also want to read: The Wing Chun Jo Fen: Norms and the Creation of a Southern Chinese Martial Arts Community.

oOo

May 20, 2016 at 12:59 am

I agree, this is a terrific book about a time, a place, and the always interesting people who populated them. The impact of all of this continues to influence what and how Chinese martial arts are taught both in San Francisco and points beyond.

May 25, 2016 at 9:02 pm

When you capture a moment in time as valuable as this, how can you not strike gold?

May 25, 2016 at 9:03 pm

In every “immigrant story” that we should embrace as a nation, there is always a wonderful hero….this is this moment in this book.

May 20, 2016 at 9:59 am

A well written article. Even as a non American there seems to be some charm coating this period and area.

Much later, in the begining of the 80’s, we were reading any CMA book we could find, and subscribing to “Inside Kung Fu” magazine. So, even at a distant land those stories are somehow part of what we grew upon.

Best regards,

Abi (Israel)

October 24, 2016 at 3:13 pm

One of Bruce Lee’s classmates told me that, in his younger HK years, Lee was hardworking, lazy, friendly and cunning. Not the model of an ideal Wing Chun student by the standards of Ip Man or his time.

Is it going too far to say that the state of Chinese Martial Arts today (as reflected into the West and now back again) is largely a product of one teenager’s bad attitude?!

October 26, 2016 at 8:37 am

I learned so much from this article, very interesting about R.W. Smith, thank you.

October 29, 2023 at 12:48 pm

Agree with just about everything that has been said. Very readable, and the author paints a nuanced picture of the Bay area CMA scene during the 50’s and 60’s, and digs deep into where, and when it came from. Like the reviewer, I also wished it was longer.