Introduction

Daniel M. Amos is one of the less appreciated, but more important, voices in the academic study of the southern Chinese martial arts. In 1983 he deposited a doctoral dissertation at the University of California, Los Angeles, titled “Marginality and the Heroes Art: Martial Arts in Hong Kong and Guangzhou (Canton).” Parts of this work were later published as articles (see here and here). Amos’ work is rich in ethnographic data, and I have discussed it in a number of places, focusing especially on his description of a Southern Mantis school and Qilin Dance Association in Hong Kong during the 1970s.

Amos’ extensive field work is valuable for a number of reasons. Most fundamentally it provides us with an ethnographic window onto a critically important era in the history of the modern martial arts. Coming on the heels of the Cultural Revolution, Amos set out to document the state of Kung Fu in the early years of its explosive growth in popularity during the late 1970s and early 1980s.

He carried out this investigation in a comparative context, looking at developments and institutions on both sides of the border separating Hong Kong from Guangdong. He also accomplished all of this prior to the emergence of Martial Arts Studies as an acknowledged research area. In short, Amos was a lone voice documenting a vitally important period that is of great interest to the field now, but which received little scholarly interest at the time.

Amos’ work went beyond simple empirical investigation. Throughout his dissertation he sought to tie the rapid rise of the martial arts to larger theoretical issues. The growing popularity of these pursuits in both Hong Kong and Guangzhou is intellectually significant precisely because in the early 1980s they were two very different places. Since the closure of their shared border in 1949, these two areas had experienced very different economic and political forces. Both had been subject to experiments in large scale social engineering. Historically speaking, they were both be parts of the same “culture area.” Yet during the course of his fieldwork it quickly became apparent that each of these areas had been marked by its own process of irreversible social change.

One would not necessarily guess this simply by looking at the state of the martial arts on either side of the border. In both cases Amos found thriving organizations, associations and societies teaching a number of styles. While official Kung Fu organizations (those backed by the government) tended to adopt a “modernist” stance, most popular groups continued to claim a direct line of transmission connecting them to the great martial heroes of the region’s past.

This is something of a paradox. The martial arts were not always all that popular in Hong Kong during the post-1949 period. Indeed, for much of the 1950s and 1960s most people tended to associate martial arts schools with youth delinquency, public disturbances and organized crime. This is a far cry from the sanitized “golden age” Hong Kong Kung Fu that is often imagined in the west. Still, the situation began to improve in the 1970s and 1980s.

The situation in Guangzhou was even more complex. Amos notes that during the Republic period the martial arts had played an important part in the life of southern China. Officially sanctioned schools were created to spread these practices to soldiers, students, government employees and the middle class. At the same time private martial arts houses, usually backed by powerful landowners, secret societies or labor unions, provided the bulk of the instruction available to the area’s working class. These smaller schools can be thought of as “voluntary associations” which contributed to the rapid growth of the region’s civil society in the 1920s and 1930s.

After 1949 all of this changed. While the Communist Party did not immediately move to ban the technical transmission of the martial arts (they even formed some of their own government backed Wushu associations), they did crack down on “feudal” practices and relationships. This is critical as local martial arts masters had always functioned in a world of patron-client relationships, where resources and access to power often moved along privately controlled lines. These modes of social organization became a major target of the Communist Party’s efforts to “modernize” and “rationalize” society. The end result was that all of traditional martial arts schools (even the ones that had supported the CCP during the civil war) were forced to shut down by about 1951. Nor could these groups easily rebuild themselves without the support of the now non-existent landowners, independent labor unions or secret societies. All of the institutions that had once supported the existence of the martial arts as a distinct social phenomenon were expunged from the new totalitarian order.

While some martial arts would still be taught in official settings up until the start of the Cultural Revolution, by 1951 they had ceased to be part of local society. In fact, civil society itself had largely been eradicated and replaced by a number of vertical linkages connecting individuals directly to the party as their sole form of social insurance. Once the society that had supported traditional hand combat practices ceased to exist, there was literally no way for these groups to continue.

Yet when Amos returned to the region for his field research a few decades later he found that the martial arts were once again thriving on a number of levels, from university sports programs to “folk” teachers in the park. They could even be found within newly created “secret societies.” More significantly, martial arts schools had once again resumed their role as “voluntary associations” and were playing an important role in the region’s newly resuscitated civil society.

How was this possible? Were these new voluntary associations really just a continuation of what had existed prior to 1949, as their mythology often claimed. Or given the depth of social disruption, were they better understood as newly created institutions, fine-tuned to survive in the hybrid world of state socialism and frontier capitalism that existed in Guangzhou in the early 1980s?

What about Hong Kong? Could the same factors explain how the martial arts functioned in these two societies, or were different models necessary? Lastly, how could looking at the martial arts help us to understand the growth of Chinese civil society after the Cultural Revolution?

Luckily readers will not need to tackle Amos’ entire dissertation to discover his thoughts on these issues. Much of his work in this area was later published as “The Re-emergence of Voluntary Associations in Canton, China,” in Asian Perspective, Vol. 19 No. 1 (1995, 99-115). Anyone interested in the social history of the southern Chinese martial arts should take a look at this article.

In truth the significance of Amos’ discussion reaches beyond the field of martial arts studies. While it is not uncommon to hear scholars in our area bemoan how poorly documented the popular martial arts have been, in truth these groups have done a comparatively good job in preserving their history compared to most other sorts of voluntary associations.

I suspect that martial arts mythology has been something of a double edged sword here. On the one hand it tempts individuals to disregard the recent past in an attempt to connect themselves directly with the more primal sources of martial prowess. Yet at the same time it gives individuals an incentive to pass on their own stories, or to write their own histories, as a way of validating their connection to the “sacred past.” These modern “folk histories” are often very revealing in the hand of a skilled scholar. As such, the evolution of the modern martial arts systems might provide us with an important window onto what was happening in other, less well documented, areas of Chinese civil society after the end of the Cultural Revolution.

Kung Fu is Dead, Long Live Kung Fu

The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) is the axis that divides not just two eras in Southern China’s martial arts history, but the area’s basic social organizations as well. Most quick discussions of the region’s hand combat place their flowering after the end of this tumultuous period. The move towards greater liberalization within both the economic and social spheres is seen as the root cause of the “Kung Fu Fever” that swept China in the early 1980s.

Still, Amos goes to some lengths to argue that this conventional understanding is actually subtly mistaken. It is absolutely true the regional martial arts, as voluntary associations, had been wiped out well before the start of this period. Individuals who had been associated with the martial arts were often seen as having “historical problems” by the new regime. A handful of them went on to become trainers in the new state sponsored Wushu programs. Yet most martial artists simply blended back into society and spent the next twenty years avoiding any public discussion of their former practices. Citing the unfortunate case of Geng Dehai, Amos reminds us that many prominent martial arts teachers who had been involved with the KMT or the secret societies were either imprisoned or executed in purges that happened between 1949 and 1951.

This suppression of “feudal practices” went well beyond the martial arts. In truth they were a minor casualty of the Communist Party’s larger social reform agenda. By about 1951 most of the pillars that had supported a once vibrant independent social and economic order had been replaced by the various party organs of a totalitarian state. Individuals found themselves wholly dependent on the state for their economic and political well-being.

In this sort of environment it is not really rational for people to attempt to create private voluntary organizations. There is literally nothing to be gained, as all “goods” now come from the state. While certain individuals continued their martial practices for their own private reasons, no one in Guangzhou was building private schools between 1951 (the year a number of local martial artists were executed or jailed) and 1966.

The onset of the Cultural Revolution changed all of this. As various factions of the party turned on each other, it quickly became apparent that loyalty to local leaders could not guarantee one’s safety. Even the military discovered that they were not entirely safe from Mao’s Red Guard. Individuals who had previously had their “historical problems” (such as a prior association with the secret societies or martial arts) cleared found that they were once again targets for attacks.

Amos reviews the literature on the period and notes that it was during the initial phase of the Cultural Revolution that all sorts of voluntary associations and secret societies began to reassert themselves in southern Chinese life. At first this seems puzzling. Given that the Red Guard was actively hunting for “reactionaries” and those with “feudal” tendencies, one might think that it would make more sense for former martial artists to go into deep hiding during the late 1960s.

Of course many did. Countless skills, manuscripts and weapons were lost during this period. Nevertheless, other groups of individuals reasoned that if the party could no longer protect them (in fact, it could not even protect itself from the social chaos that had been unleashed), their best bet was to begin to form secret networks of informants, friends and supporters. Martial artists, many of whom were former secret society members, had something of a head start in the rush to “privatize security” that occurred throughout the Cultural Revolution.

These individuals did not form open public schools. That would have been suicidal. Instead they tended to take on one or two trusted students from their local work unit. They formed relationships with some trusted officials above them, and slowly expanded their network of contacts. As these protective networks grew they became more enticing to those outside them. By the end of the period these secret teachers had networks of dozens or hundreds of highly loyal and disciplined students. Not only did the reemergence of interconnected networks of voluntary associations predate the end of the Cultural Revolution, their creation was a direct result of the decay of the totalitarian social system that this crisis triggered.

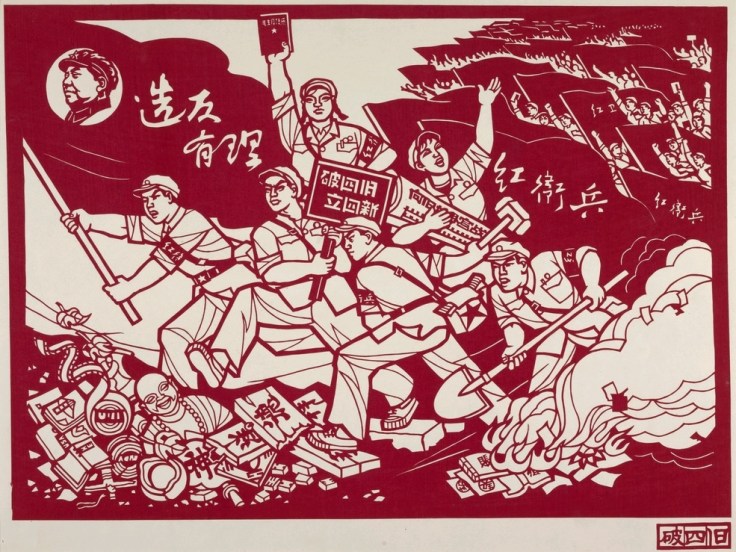

![Another poster advocating the extermination of the four olds. However this time the campaign has been given a regional spin. The four crossed out words are "Collective Memory, The Old City [of Guangzhou], Cantonese, and Old Guangzhou Natives." The central image is of a famous sculpture of five stone goats in a public park which has become something of a symbol of the city. Such campagins were effective in destroying the region's preexisting civil society. Source: redscarfmuseum.blogspot.com](https://chinesemartialstudies.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/collective-memory-the-old-city-cantonese-and-old-guangzhou-natives-redscarfmuseum-blogspot-com.jpg?w=682&h=384)

Understanding the New Generation of Martial Arts Associations

Amos notes that voluntary associations arise whenever social and economic upheaval opens a space in the pre-existing social order. For an anthropologist his model of civil society is strikingly utilitarian and functionalist. It is the rational expectation of material benefits (or the minimization of risk) that called these groups, including martial arts societies, into being.

When discussing life in Guangdong, Amos outlines five different types of social organizations, examples of which can be found in the world of the martial arts. First we have the “official” and “semi-official” organizations. Physical culture bureaus, staffed with party cadres, would be an example of an “official” association. These groups exist to create and promote state policy.

“Semi-official” associations (such as the Canton Martial Arts Association) are usually chartered by officially backed organs and might share some personal with them. However, these groups are often responsible for raising their own funding, and their primary orientation seems to be towards the public. For instance, the CMAA both oversaw some official Wushu programs, but it also helped local martial arts teachers to rent spaces for their classes in area high schools. These classes were quite lucrative and helped teachers to establish a reputation. In return the CMAA received a cut of the tuition which helped to finance its operation.

“Private” organizations still existed within the realm of government oversight, but shared no personal or revenue with the “official” associations. The private classes of individual teachers or Wushu coaches held in the evenings in local high schools would fall into this category.

Amos notes however that this (relatively widespread) classification of groups in socialist societies misses some of the interesting developments that took place during the Cultural Revolution. Here we saw the creation of social structures that had no connection to the state. These were in effect pure civil associations. Certain officials might turn a blind eye toward their activities, but they had derived no support (moral or otherwise) from the state.

Amos breaks this last group into two further categories. First he discusses archetypal “voluntary associations.” Within the world of the martial arts during the late 1970s, these found expression in the activities of the various “public park masters.” During the Cultural Revolution such individuals had started to build networks of students and supporters within their work units. As conditions liberalized and individuals began to look for new modes of self-expression and entertainment, the popularity of these informal martial arts classes skyrocketed. For the first time the Qigong and Kung Fu masters were able to hold large public classes and begin to charge tuition. In some cases the proceeds from this early growth was enough to support the construction of larger patronage type organizations.

Amos notes that many of these individuals (and their students) had little love for the Communist Party. The same was actually true for most of the Wushu teachers who worked for state sponsored “official” organizations as well. Still, given the nature of their jobs they were not free to express their grievances. It was the Communist Party’s endorsement of their work that gave it both social respect and a sense of legitimacy.

The public park masters were in a very different position. They tended to draw legitimacy from a rich hybrid mythology built up both around themselves and their styles. Students told tales of how their teachers fought corrupt officials and bullies during the Cultural Revolution. These stories (often vastly exaggerated) tended to dovetail with the preexisting creation narratives of the styles that the individuals taught. In that way this new generation of teachers became tied to the “knight-errant” model of social activism, and provided their younger students with a role model suitable for emulation.

Some individuals held views that were even more antagonistic towards the state. Amos classifies the institutions created by this last group as “secret societies.” He notes that the basic function of secrecy is to provide protection. This secrecy was sometimes necessary given the quasi-criminal behaviors of individuals who were embedded in the “frontier capitalism” of the Pearl River Delta. In other instances Amos notes that young people created secret martial arts groups as a cover for political discussions and projects that might result in their arrest if they were discovered.

Some of these ‘secret societies’ appear to have been spontaneous creations formed by primary sodalities of young people who had been sent out to the country together. Others were forged in “work units” in the cities by individuals who may have actually been members of a triad or martial arts association prior to 1949.

How should we think of these new voluntary associations, including both the park schools and secret societies, during the late 1970s? Many of these groups consciously appropriated stories and images from the Republican period. In some cases they were even led by legitimate lineage holders. Were these movements the reassertion of long dormant cultural institutions? Or were they something fundamentally different from what had come before?

At this point we must stop to consider what we actually mean when we refer to the “martial arts.” In popular parlance these practices are generally defined as a specific technology of violence that is passed on through time by specific teaching structures. This emphasis on institutions and social structures is what makes these arts different from pure military technologies. They allow for cultural knowledge and concepts to be conveyed as well. Still, the basic definition that most students of the Chinese hand combat systems seem to subconsciously endorse is the embodied transmission of a physical technology of violence through some sort of lineage.

A social scientist (such as myself) or an anthropologist (like Amos) is likely to approach this question somewhat differently. I think that we would agree that all of these basic elements mentioned above are important. Clearly there is an embodied tradition, a supporting super structure of beliefs and identities, and some set of social institutions. Yet I think that most of us would argue that it is this last element that is the most critical.

The martial arts have always existed as an important element within a larger framework called “Chinese popular culture.” They define themselves in relation to other elements of this framework including social norms, cultural practices, religious beliefs and even prevailing economic intuitions. It is their existence within this broader framework that allows them to attract potential students, to bestow new identities, and to offer a rudimentary social safety net to marginal individuals. In short, this is what allows them to perform all of the functions identified by Amos in the pre-1949 period as well as the post-1966 era.

When looking at the history of the martial arts it is not all that hard to find examples of martial arts traditions that actually adopt new technologies over time, yet maintain a remarkably stable identity. Shaolin Kung Fu has existed for a long time, yet as Meir Shahar has so masterfully demonstrated, the actual range of skills being taught tended to change quite a bit from decade to decade.

Nor is this the only example that we could point to. Still, Shahar’s work is a very nicely researched illustration of the fact that identities and social institutions within the martial arts are sometimes more stable than individual technical practices, which can evolve in response to local conditions. The social institution provides a deep sense of continuity and tradition, which the technological transmission provides the environmental relevance.

This same basic pattern is evident in a number of styles in Hong Kong after 1949. Recall that the city had the good fortune to host a number of masters who fled the Communist Party’s advance. Ip Man preserved the social institutions and identities associated with Wing Chun while looking for ways to make its practice relevant to the new generation of young, modern, students. Nor is his story particularly unique in this regard.

Amos’ field work is fascinating as he illustrates the opposite possibility. The post-1949 period was far too corrosive to allow for a traditional transmission mechanism. It was not the chaos of 1966-1976 (as is normally assumed) that destroyed the region’s martial culture. Rather it was the seemingly uneventful, but bureaucratically very efficient, period between 1949 and 1965 that effectively killed popular Kung Fu.

While the execution and arrests of martial arts masters was disruptive, what was far worse was the systematic destruction of the social, cultural and economic worlds that had once supported these practices. Amos notes that it is hard to underestimate how completely life in Guangzhou was transformed between 1945 and 1955. While the technical transmission of certain martial practices was preserved in universities, sports associations and private practice rooms, there was simply no public space in the new totalitarian society for their institutional super-structure. In Guangzhou it was the identities, culture and social institutions that died, even when isolated elements of the technical transmission managed to survive.

When discussing the city’s new “secret societies” in the early 1980s Amos notes that there was an unbridgeable gap separating them from their earlier namesakes. Whereas prior Triad members had been illiterate and steeped in a world of oral lore, ritual and theatrical performance, the new generation of societies tended to be composed of middle class kids, frustrated with the state, but highly literate with a modern outlook. As Amos put it, regardless of what these individuals thought about Mao, all of the martial artists and society members of Guangzhou in the early 1980s were unmistakably the products of “Mao thought.” They were all educated, rational materialists who wanted nothing to do with the religion, rituals or superstitions of the past.

Even if their elders and teachers wished to pass on these practices, there was no guarantee that their younger students would accept them without significant alterations and repackaging. Of course this was exactly what happened in the world of Qigong and other “traditional” health practices. The cultural world of ancestor worship, lineage patronage networks, guildhalls and secret societies that had supported the world of Kung Fu was simply gone. While new institutions and associations were created, it seems that Amos would likely classify these as “invented traditions” or “folk histories” rather than the legitimate continuation of preexisting institutions.

Conclusion

In the social realm nothing is static. Identities and practices undergo continual change as they are passed from one generation to the next. As such it is useful to remind ourselves that just as the world of Guangzhou in 1949 has vanished, the environment that Amos encountered in the early 1980s has also passed into history. While his observations lay a foundation that is useful for thinking about what we see today, the actual environment that currently exists in Guangzhou and the surrounding region is once again different from what he described.

Over the decades martial identities in Guangzhou have had time to mature, mix and hybridize with other institutions and practices. It is my sense that there is more of an appreciation for “traditional culture” is some (though not all) of the area’s martial arts community than what Amos observed in his fieldwork in the early 1980s.

While the process of social and economic opening that he credited with boosting the popularity of the martial arts has continued to roll forth, the actual popularity of these practices has declined. At one point in his article he mentions in an offhanded fashion that the martial arts are at heart a “youth culture.” Unfortunately in the current era that has ceased to be the case. Still, how Amos’ work might help to explain the current decline in popularity of these hand combat systems will have to be a subject for another post.

Two points become clear as we conclude our discussion of this article and both are related to the question of culture. While the end of the Cultural Revolution opened a space for the reemergence of civil society (comprised of a dense network of overlapping voluntary associations), the form that it took was quite different from what had existed during its initial flowering in the Republican era. Thus the nature of Chinese civil society is not so much a function of “Chinese culture” as it is the specific institutional opening created by the state.

This then leads to our second conclusion. While individual voluntary associations (including those in the martial arts) will always have strong incentives to claim that they represent a “pure” and unchallenged cultural past, in fact they are intimately shaped by all of the other institutions within civil society that they interact with. Given that state policy can radically reshape even the most basic of these institutions, we must be very careful ascribing the characteristics or behavior of any of these groups to some sort of “fundamental” or “essential” cultural identity.

Had the Communist Party of the 1950s been less efficient in their destruction of preexisting social structures, the martial arts traditions of Guangzhou might actually look very different today. That very fact would suggest that the martial arts need to be understood as more than a technology of violence or a system of lineage transmission.

oOo

If you enjoyed this post you might also want to read: Cantonese Popular Culture and the Creation of Wing Chun’s “Opera Rebels.”

oOo

February 21, 2017 at 3:12 am

Hi, I am curious about one thing you wrote about here: “The end result was that all of traditional martial arts schools (even the ones that had supported the CCP during the civil war) were forced to shut down by about 1951.”

Did this policy of shutting down private martial arts schools extend beyond Guangdong? In other words, were all private martial arts schools throughout the entire China forced to close down in 1951? Or were private martial arts schools outside of Guangdong still allowed to exist?

Thanks!

February 21, 2017 at 9:18 pm

Hi Artin. I would suggest checking out Amos’ article for a much more detailed discussion of this point. Long story short, this was not restricted to Guangdong. We are talking about national level changes in very fundamental social structures. But China is a huge place so who knows what happened in every village. Still, Amos’ more general argument is that no one had to “shut down” the schools. When the entire system of property ownership and social organization was transformed there was just no way to keep them open, and people weren’t really interested in them anyway as they could no longer fill their traditional social duties. So yeah, that would go a long way towards explaining the very rapid decline in folk martial arts practice during the 1950s and 1960s in the PRC.

February 22, 2017 at 1:32 pm

Hi Dr. Judkins,

Thanks for the reply! I had another quick question concerning these traditional martial arts schools. In your book, The Creation of Wing Chun, I read the following passage:

“A few possibilities immediately present themselves. It is often asserted that Guangdong’s martial arts of the Hung Mun group (including Wing Chun) have their roots in anti-government secret societies.The founding mythology of these schools claims as much. It is conceivable that the new generation of martial arts schools were modeled on secret society chapters. One should also remember that membership in the societies spiked in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; at exactly the same time we see an explosion in the number of PUBLIC MARTIAL ARTS SCHOOLS.

This theory, often implicitly advanced by practicing martial artists, has a number of critical shortcomings.To begin with, complex ritualized initiation ceremonies, including the use of blood oaths and divine theater, were always at the heart of the secret society experience. These things are totally missing from the sorts of martial arts schools that developed in the nineteenth century. Furthermore, one could become a master of a secret society, and even found a new chapter, simply by paying more for your initiation. No actual skills had to be conveyed in the process. Yet martial arts schools are centered on the mission of conveying physically embodied skills. The one thing they absolutely must have is a functioning teaching structure. While the ritual transfer of esoteric knowledge was important, secret societies never really operated as schools.

This is not to say that there was not substantial overlap between the world of martial artists and that of gangsters and secret society members. Clearly there was. Secret societies might even use martial arts schools as recruiting devices. However, it is interesting to note that these individuals always kept the two bodies institutionally and organizationally distinct. There was never any sense that a commercial martial arts association and a secret society were the same thing, or even shared a common organizational structure” (100).

In your book, you wrote about public martial arts schools like the Hung Sing Association. However, in the article above, you wrote about private martial arts houses and traditional martial arts schools. Are these three terms synonymous? Because if they are, from what I can understood then, private martial arts houses were not the same thing as secret societies, despite common overlaps. I just wanted to make sure I clearly understood the distinction.

Thanks!

-Artin

February 23, 2017 at 10:44 am

Hi Artin. I didn’t have any specific intention in mind when I used the term “public martial arts school” in the book and “traditional” martial art in the later blog post. In the first case I was talking about how students were recruited. In the second I was probably thinking more about the type of martial art being practiced (in the west its common to referrer to all of this as the “traditional martial arts” without that necessarily carrying any detailed sociological meaning. In daily use it just means “not sanda, not kickboxing, not MMA”).

Regarding your final question, yes, that is correct. Martial arts schools (whether you want to call them “public”, “traditional” or what ever) are not the same thing as secret societies. Clearly there is overlap. Again, Amos’ ethnography conducted in the late 1970s is a great source on this. I would suggest pulling a copy of his dissertation. He notes, for instance, that the HK police were always worried that triads and secret societies had infiltrated or were running some of the area’s martial arts schools. In their estimate (likely inflated) I think this was up to 1/3 of the schools in HK. And to be totally clear, there have been some quite notable cases in America were various Tong’s hired martial artists to train enforcers, or even supported some public schools. Charlie Russo talks about in California in his recent book. But the triad and the school were always organizationally distinct entities. Membership in one was not membership in the other. Obviously if you want a martial arts school to be able to function as “a front” for a criminal or revolutionary group you need to keep it at arms length or it can’t do that job.

Nevertheless, most martial arts instruction (at pretty much any point in history) never had anything to do with triads or secret societies. In terms of social function and organizational structures these things are pretty distinct (even if they do tend to appear in the same folklore).