***Today’s post continues our discussion of economic markets and modernity in the Chinese martial arts. This essay, first posted in May of 2013, was one of my first attempts at hashing out these questions as they related to advertising strategies in Republican era martial arts schools. Enjoy!****

Introduction

Much of our modern writing on the Chinese martial arts is premised on the examination of difference. Nor is this an abstract categorization of dry facts. Our discussions always seem to run along a similar track. Of all of the techniques, styles and teachers out there, we want to know which one is “the best.” It should come as no surprise that the “hand combat industry” (and it is an industry, complete with its own markets, trade organizations, lobbying efforts, and publications) has no lack of individuals offering to answer this question for consumers.

Different sources of authority are sometimes claimed. Occasionally a writer or teacher will have had an extensive career in the military or law enforcement. A long and illustrious record on the tournament circuit is usually taken as a sign of expertise. We also encounter instructors whose credentials are more esoteric. Specifically, these writers or teachers note that they are part of an “alternate” or “lost” lineage of some esteemed fighting system. Often it is claimed that this lineage is somehow older, purer or just more hardcore than the one you belong to.

These sorts of competitive lineage claims have become a staple for major publishers. Just take a look at the monthly covers of the any martial arts magazine (Blackbelt, Combat, Kung Fu Tai Chi ect…) and you are sure to find at least one story about an “alternate lineage.” Variety facilitates competition and comparison; together they make for interesting reading.

In fact, the media surrounding the martial arts are central to the existence and continual rediscovery of “lost lineages.” During the early 19th century (before the market reforms of the Republican era) China had a huge number of local fighting styles. Most of them were very small village or family affairs. A lot of what they did actually focused on militia training, opera or banditry. Many of these styles did not actually have names, though there were some notable exceptions.

Why did so many of these pedagogical systems lack names? They were not studied so much as a particular “style” of fighting (or in the case of opera, acting). They simply were fighting (and acting). Later in the 19th century as the demand for martial instruction increased, and the number of reasons it was pursued diversified, it became necessary to market these skills on a broader scale than had been undertaken in the past. Names and shiny new creation myths began to appear as the fighting techniques of the previous generation were increasingly repackaged as a “martial commodity.”

The martial arts publishing industry is not new. Already in the late 19th century Guangzhou and Hong Kong publishers were churning out cheap chapbooks of martial techniques and elaborate swordsmen novels full of the exploits of fictional schools. During the 1920s and 1930s there was a literal explosion of training manuals and newspaper stories about the exploits of local heroes and martial artists. As the marketplace got more crowded, product differentiation and advertising became more critical to the actual careers and business success of boxing instructors.

The debates that we see played out on the covers of our current Kung Fu magazines are not much of a departure from the past. This sort of competition and bickering has been a part of the world of the “authentic” Chinese martial arts for over 100 years now. Yet why the persistent narrative of the “lost lineage?” These stories tend to be among the most controversial, yet they are seen throughout the Chinese martial arts. Why not simply develop a new identity and market the art as your own creation (or your teachers)? Surely this would be easier than an eternal public debate as to the legitimacy of your practice?

“Martial Arts” or “Martial Brands”

Media provides a space in which the Chinese martial arts can develop their competitive discourse, build reputations and attract students (or perhaps customers). How we should think about the relationship between the media and the development of hand combat (in either the west or China) is a difficult question.

Clearly the existence of print capitalism in both hemispheres was key to the explosion of interest in these arts between roughly 1890-1960. This media coverage did more than simply popularize the existing arts. The structure of these arts was also influenced, sometimes in profound ways. Yet a variety of other factors were also at play. How much impact did the media discourse ultimately have on outcomes?

In a recent paper titled “Universalism and Particularism in Mediatized Martial Arts” (2013) Paul Bowman has argued that we must be cautious when applying political concepts (such as cultural appropriation, hegemony and post-colonialism) to studies of the relationship between the media and the development of the martial arts. This is not to say that the media has not had an important impact on the development of the arts. I think that Bowman would argue that it clearly has.

Rather, media discourse tends to work in non-logical, non-purposive ways. As such many of our political concepts fail to catch what is actually going on. Worse yet, they tend to mischaracterize the actual nature of the interaction between the media, the traditional fighting arts, and various cultural groups.

Bowman makes many excellent points in this paper and I agree with his basic conclusions. I hope to engage the substance of his remarks more fully in the future. However, I was struck by a particular line of thought that emerged within his argument which might shed some light on the ultimate origin of the “lost lineages” of the Chinese martial arts.

Bowman notes that the Asian fighting styles (not just the Chinese ones) have been undergoing a century long period of reorganization in which the multitude of small village and family traditions has been compressed, morphed and twisted in such a way that there are now fewer styles, and fewer names by which they are known, than there were in the past (say the 1920s). He asks whether after 100 years of transmutation and distortion we can still talk of “martial arts” or whether we should instead be thinking and speaking in terms of “martial brands?” In what ways, if any, are these fighting styles still traditional arts?

The implied answer would seem to be “in very few if any.” Of course this is an area where we must pay attention to our definitions. If one starts by assuming that the “arts” are produced by “artisans,” individuals who are dedicated and bound to a craft not just by economic incentives, but as part of an all-encompassing social structure, than Bowman is clearly correct.

In that respect we really have not had any traditional “arts” (or artisans for that matter) since the transition to a capitalist economic structure in the mid-19th century. This same transformation has taken a little longer in Asia (if only because they collectively started later) but China, Japan and Korea are now all undeniably market driven industrial societies.

Nor is Bowman the first to make this argument. The entire premise of the Arts and Crafts Movement championed by William Morris, and so important to the early 20th century history of architecture, was that the type of work promoted by the industrial revolution literally degraded our lives. It was corrosive to any sort of authentic organic community. Originally the goal of the movement was to advance social reform by supporting the work of artisan builders and trades people. They in turn would produce more authentic physical artifacts and spaces that benefited individuals and communities.

Of course the entire thing was a pipe-dream, at least on a political and economic level. The Arts and Crafts Movement was not really anti-modern or anti-capitalist. It was simply another expression of modern consumerism in quaint packaging, advertised heavily in period magazines and newspapers. Almost all of the movement’s “artisanal” furniture was actually produced in factories of the sort that Morris decried. Demand was simply too high to do anything else. By the time the movement hit its high water mark one could even order entire ready-made houses, complete with construction crews, through the Sears catalog.

I bring up the “Arts and Crafts” movement as it overlaps and suggests some important features about the initial emergence of the martial arts. On the surface this appears to be an anti-modern, anti-commercial movement that was quickly subjugated to the dominant social order as it became a mass phenomenon. But upon closer inspection it becomes readily apparent that it was always an essentially commercial aesthetic. What appeared to have been a popular movement, or a way of life, was really a “brand.” It could not exist without the capitalism and industrialism it so loudly protested.

Likewise in China and Japan there had been hereditary soldiers and retainers, opera performers and militia members, who trained in weapons and hand combat during the Ming and Qing dynasties. Obviously all of these individuals had to make a living, but what they did was as much a matter of social convention as anything else. Peasants guarded their fields out of sheer necessity. Opera performers were a trapped social sub-caste with few other viable means of employment. Likewise those born into families bound to hereditary military service studied the martial arts because they really had no other choice.

Perhaps we could think of these individuals as “artisans” in their approach to their work. Chinese soldiers were capable of taking pride in what they did which was not really related to their meager pay and poor living conditions. Opera performers were just the same. Yet when the martial reformers of the 1930s, or even the 1890s, attempted to reconstitute these fighting styles and promote them to the public, they fundamentally failed to capture the essence of this earlier social reality.

How could they? The Chinese economy and society had evolved and fundamentally changed. The industrial revolution had started to spread, cities were growing rapidly and more of the economy was invested in fully monetized markets. Martial reformers like Sun Lu-Tang were attempting to sell hand combat instruction to a middle class urban market in places like Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou which did not even exist one generation before.

This was an era characterized by the sudden emergence of choice. One could choose to study boxing, or one could choose to study western ballroom dance. In point of fact dance was actually the much more popular discipline. Likewise in Beijing one could choose to study Taiji, Bagua or Xingyi Quan.

Suddenly everything about these arts, from the spaces where they were practiced, the fame of their teachers, what was said about them in the press or their creation narratives, became a means for consumers to evaluate what they wanted to buy. It might be tempting to assume that things like the creation narratives “changed” when they became advertising tools in the current era. Yet this is what they really had been all along. It is their essential function.

Yes, the traditional fighting arts of China are in some very important respects commercial “brands.” All of the institutions that surround these pedagogical methods exist basically to channel consumer behavior. Often they do this so well that we don’t even realize what is going on. What we see is “traditional Chinese culture.” We are unaware that much of this is actually a comparatively recent invention. For example, it might be a unique vision of “Chinese culture” designed to comfort a displaced country youth who suddenly found himself in Shanghai during the 1920s or Hong Kong in the 1950s.

Print Capitalism, Competition and the Myth of the Lost Lineage.

Obviously there are limits to any metaphor that we adopt. From the perspective of economic history it might not make a lot of sense to call modern hand combat instructors “artisans.” Yet from some other perspective that label may work just fine.

Nevertheless, I would like to explore the notion that we can think of the various martial styles as “brands” and see whether or not it is useful. What sort of explanatory work can it actually do for us?

Recall for instance Bowman’s observation that in the last century we have seen a lot of change in the Asian (and Chinese) martial arts. In the 1700s there appear to have been a great variety of small local and family teaching traditions. Later in the 19th century many of these styles start to disappear, combine themselves or otherwise adapt. Likewise a number of style names exist which also undergo consolidation until we reach the current era. Today we have fewer commonly used style names than one might expect, but each one of these “brands” contains a greater number of differing, evolving and sometimes contradictory sub-traditions than one can easily explain. For example, consider the vast variety of 20th century practices that have adopted the Japanese name “Karate,” or some variant there of.

How can we think about this general consolidation of identity? From a purely cultural or historical perspective this might appear to be damaged due to China’s conflict with Western imperialism. Yet this seemingly reasonable conclusion ignores the fact that something similar has actually happened once before, during the Ming dynasty.

During the second half of the 16th century martial arts in general, and unarmed boxing in particular, started to become very popular with the literate elements of Chinese society. Literally dozens of still extent fighting manuals were published and biographies of important martial figures were recorded for posterity. Further, many of these fighting techniques were consolidated into specific “styles” and “schools” which competed with one another for elite attention and patronage. Only a handful of these movements actually survived into the 19th century (Shaolin and the ancestor of modern Taiji being the best known examples). Still, the basic pattern holds. During the late Ming many small, presumably anonymous, fighting systems were folded together into more easily discussed and compared “traditions” and “schools.”

China did face problems with pirates in the 1550s, but this hardly amounted to “imperialism.” And the ultimate fall of the dynasty was still a century off. What seems to be similar between both of these periods, the second half of the 16th and the 19th – early 20th centuries, is a sudden explosion of cheaply printed easily acquired books on the martial arts. Fictional stories featuring martial artists were popular in both periods. Even common household encyclopedias would contain entries on martial topics and promised to teach their owners a few key techniques.

While discussing the growth of nationalism in Europe Benedict Anderson famously made a similar observation. Originally Europe was a patchwork of differing spoken vernacular languages. France contained literally a dozen spoken dialects, not all of which were mutually compatible with one another. Spain and Germany were if anything even more polyglot. There were also substantial differences between the dialects of English spoken in the south and those that were used in Scotland. A few of the major dialects had names, but most were just regional variations and not considered to be particularly important. After all, Latin was the language of all serious educated people.

So what changed the situation? The printing press. So few individuals actually read Latin that it only took a couple of decades for printers to saturate that market. After that they needed to find new readers, and they did this by turning their attention to works printed in the various vernacular languages. However, it is simply not possibly to have a printing shop in every hamlet in Normandy, or to print an almanac in a dozen different dialects of French.

Competition in the book market decided where the regional centers for printing and distribution would be. They in turn determined which local dialects would be used in publications, and everyone else adapted. With remarkable speed the various indigenous dialects of Europe were compressed and whittled down to a handful of “print vernacular” languages. Further, this was (at first) a remarkably apolitical process. The creation of Europe’s various linguistic blocks owed as much to competition in the publishing industry as it did to anything else.

Printing had a similar effect in China. Douglas Hamm, in his study of the emergence of the modern martial arts novel in late 19th century Guangdong (Paper Swordsmen, Hawaii UP, 2006.) even noted a move away from classical Chinese towards a standardized “Cantonese Dialect” in these locally printed martial arts stories. This move nicely paralleled the linguistic processes that Anderson noted in Europe.

Leaving the more basic linguistic exercise aside for the moment, the explosion of the Chinese printing industry, first in Guangdong in the second half of the 19th century, and slightly later in places like Beijing and Shanghai, had other critical effects on the market for hand combat instruction.

To begin with, martial arts romances sold very well. They were mass produced as penny novels and were serialized in newspapers to encourage readership. These novels helped to spread (often recently invented) martial norms and expectations. Likewise simple instructional manuals were also popular. And audiences never tired of reading about the exploits of their local heroes. Suddenly it became not just possible, but necessary for instructors to advertise their skill and reputation beyond the local community. I suspect that it was the emergence of a vibrant print market that effectively changed the various local fighting styles into commercial “martial brands.”

Once this fundamental economic shift was made there was no going back. The traditional economy that had supported village militia instructors or hereditary soldiers was being disrupted at a furious pace. Nostalgia for a simpler past became just one more aspect of the more popular “martial brands.”

A few styles profited immensely from this shift in the nature of the martial arts. The Hung Sing Association in Foshan, which taught Choy Li Fut, was well positioned in the local economy to shift to a public commercial teaching model and it began to aggressively propagate daughter schools across the Pearl River Delta.

Other traditions, especially those with relatively large followings (the various Hung Kuen movements) or those located along important trade routes (such as White Crane in Fujian) were also well situated to set up public schools, attract students, and build their reputation. However, as the reputation of these large players spread, many smaller styles suffered or disappeared. Young men who went to the cities seeking work might now join the Hung Sing Association rather than following their village style. Further, coverage in the local media helped these large local schools to not just fend off the local competition, but to really reshape how individuals thought about the martial arts in general.

Instructors from smaller traditions were thus left with a choice. There was a good market for martial instruction, if you could break into it. To do so they could either attempt to create their own brand, in the mode of, and competing directly against, one of the larger styles. Often this meant transforming a local tradition into something more formalized, complete with a name, lineage and illustrious creation myth. Or they could attempt to ingratiate themselves with one of the more successful local “brands.”

Reading between the lines in many existing style histories, it appears that many martial artists and younger instructors actually just retrained and joined larger, more dominant, schools. One must suspect that this process probably lay behind at least some of the stories we frequently hear of promising young teachers being defeated by established masters who then accept them as their students (and eventually assistant instructors.) The case of Leung Sheung and Jiu Wan in the Wing Chun tradition both come to mind as individuals who had extensive prior training, yet attached themselves to a new lineage/school structure. These better documented cases don’t even contain the common drama of the “challenge match.” Again, if we think of the modern Chinese arts as “brands” or “franchises” this sort of mobility makes a lot of sense. Talent attracts talent.

However it would appear that there have been numerous cases where local martial artists wished to capitalize on the marking power of the dominant style or “brand” but for one reason or another could not officially enter the new institution or retrain. The very rapid spread of Plum Blossom Boxing across northern China in the late 18th and 19th century is a good example of this.

Members of this style, sometimes associated with millennial folk religious movements, were a common fixture on training grounds and at village markets in a number of northern provinces. Today there are a very large number of “alternate lineages” within the Plum Blossom tradition, some of which share more commonalities than others. Practitioners of the art occasionally point to this proliferation of clans as evidence of the great age of the art. However, we actually have some good documentation on the history of this particular style.

It appears that in the second half of the 19th century a relatively large number of small local fighting styles, some of them more closely related than others, started to declare themselves “Plum Blossom” schools by fiat, essentially appropriating what was a regionally very successful brand, without having to totally overhaul their teaching structures. In this way the total number of unique local styles in the region was reduced, and the relationship between the name “Plum Blossom” and any fixed body of techniques was stretched and twisted, just as Bowman noted for the Asian martial arts more generally.

Of course it should be a matter of concern if other institutions begin to appropriate your brand name. If their teaching is substandard they could very well dilute the market power that the main tradition has built up and cultivated in the local imagination. In fact we do know that leaders of 19th and 20th century fighting styles were concerned with their brand’s “images.”

Esherick reports one very interesting example of “image policing” in his discussion of the relationship between Plum Blossom boxing and the aftermath of an outbreak of anti-Christian violence in 1897 (The Origins of the Boxer Uprising. California UP, 1985. pp. 151-159.).

Zhao San-duo was a noted local Plum Blossom teacher who had a few thousand students and disciples (including many yamen clerks and secretaries) in the Liyuantun region of Shandong. He was probably not a wealthy individual, but his father was a degree holder and he seems to have had some amount of local influence. While he initially resisted being caught up in local events, he ultimately could not withstand the demands to back his fiends and students in the face of persistent communal violence.

During the spring of 1897 he was effectively pressured by his students to become involved in a dispute between the local community and the area’s Christian population. A church (still under construction) was attacked, homes were looted and many people were injured in the clash (one person was reported to have been killed). The Christians were effectively driven out of the local community and the site of their former church was reallocated as a village school.

This action was well received locally and local officials were sympathetic to Zhao and his cause. However, from that point forward he increasingly aligned himself with radical (and sometimes even anti-Manchu) figures. This trend worried the other elders of the local Plum Blossom clan. They did not want to be associated with community violence, anti-Christian violence or even the suggestion of sedition.

These elders met repeatedly with Zhao. However, when it was clear that he would not change his path they agreed to part ways, but forbade him to teach or practice under their name. In effect, worried about the damage and disgrace that he would bring to a very successful brand, the Plum Blossom clan excommunicated the increasingly revolutionary Zhao.

He selected a new name for his style, the Yi-he Quan (Boxers United in Righteousness). This should sound very familiar to students of late 19th century Chinese history. Just as the elders feared, the subsequent actions of the Yi-he students in the Boxer Uprising severely damaged the fortunes of martial artists around the country.

Clearly “brand maintenance” was a consideration for the larger and more successful schools. They stood ready to repudiate those who sought to free-ride off of their reputations. Ergo the great value of the “lost lineage” story. By constructing an alternate past (or more precisely, a different variant of the original brand’s “invented tradition”) local boxers had a ready-made explanation for their complex relationship with the dominant local tradition.

So Why Does Anyone Ever Create a New Brand?

To recap, we began the 19th century with a very large number of small village and family fighting traditions. These pedagogical institutions may or may not have even thought of themselves as “styles.” In many cases they were simply practical solutions to pressing problems (like organizing a crop-watching society, or training caravan guards).

In the second half of the 19th century the local economy started to change. Particularly in the south and the east trade heated up. New forms of manufacturing were created and the economy became increasingly monetized. Urban development expanded and there was an explosion in the publishing industry. This allowed a few fighting traditions to reposition themselves in such a way that they dominated the emerging local market (Choy Li Fut in Foshan, Xingyi in Baoding etc….).

The changing local economy puts pressure on the original fighting arts. Increasingly they must either fade, or realign themselves with larger, more economically successful styles. Sometimes this is done cooperatively, which results in a rapid spread of the dominant brand through “franchises.” Other times a smaller school simply appropriates the “brand” and adjusts its creation myth accordingly. Given the highly interconnected nature of the hand combat community before the start of this process, they may even have some legitimate claims to do so. The end result is the emergence of one or more “lost” or “alternate” lineages and, once again, the rapid expansion of the brand name.

We know that certain brands did spread quickly in the late 19th and early 20th century. Taiji Quan and Bagua are classic examples of this, but so are White Crane and Hung Gar in the south. Jingwu, the “Pure Martial” movement out of Shanghai, modeled in some ways on the YMCA, was the first really successful “national brand.” It managed to establish itself throughout all of the major cities of eastern and southern China, and much of the South East Asian diaspora as well.

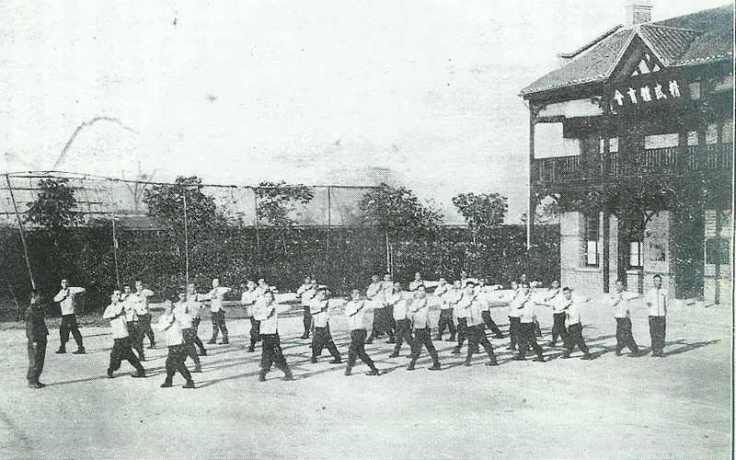

Jingwu (which was actually run by a group of intelligent you businessmen) carefully observed and learned from the experience of previous groups. Rather than relying passively on newspaper stories and martial arts novels they actively cultivated new ways of using the press and advertising in magazines in an attempt to spread their message of national salvation. The Nationalist Government studied these efforts in detail and appropriated them in the creation of their own martial brand, the highly politicized “Central Guoshu Institute.”

Their involvement with the media went well beyond newspapers and magazines. The government increasingly turned to film and radio to help spread their vision of the martial arts. In fact, it was actually through the mediums of print, radio or film that most individuals in the 1920s-1940s first came in contact with the martial arts.

Given how effective these branding exercises could be, and the importance of the “first mover advantage” in any market, the real question quickly becomes why would any inheritor of a small family or village style ever create a new martial brand in the first place? Why pay the start-up costs of creating your own brand when you can ride on the coat-tails of someone else?

Consider Wing Chun. I am not all that surprised that a number of “lost” or “alternate” Wing Chun lineages have been discovered in the last few decades. The traditional martial arts have never really fit into the narrow vertical silos that “lineage ideology” imagined. Most people have a variety of resources and teachers, and remember, prior to the second half of the 19th century, what they taught might not have been formalized in the same way that it is today.

In short, I am sure that those Cantonese Opera actors who survived the Red Turban Revolt taught a lot of stuff to a lot of people. And I know for a fact that Ip Man hung out with a variety of individuals as a youth. Given the popularity of the Wing Chun franchise it is not really a surprise that some of these smaller traditions currently want to identify themselves as part of the Wing Chun Clan, rather than say the White Crane lineage. After all, in the modern world you must have a name, you must have a lineage, and you must have a story about where you came from. Simply saying “I teach a small village style from Shunde” is not be enough. The market forces people to take a stand on these things. That is no surprise at all.

I think the more interesting question is why does Wing Chun, as a brand, even exist? The answer to that puzzle is really quite instructive and it demonstrates that the flexibility of the branding exercise has its limits.

Readers will recall that while Leung Jan (a traditional doctor in Foshan from roughly 1850-1900) usually gets acknowledged as the first generation of modern Wing Chun, he had no intention of teaching publicly or opening a school. This isn’t really a surprise as in his generation there simply were not a lot of ways to easily monetize one’s skills in the martial arts, especially if you were already running a successful full time business.

It was his disciple, Chan Wah Shun, and his student, Ng Chung So, who really established Wing Chun as a publicly taught martial art between 1903 and 1930. This period was also the height of Hung Sing’s domination of the local landscape. Beyond that, Hung Gar was also a very popular local tradition. And in reality Wing Chun shares some points with both of these arts. In particular, Wing Chun is actually pretty similar to many of the softer styles of village Hung Kuen that you see along the coast leading up to Fujian.

So why did Chan Wah Shun and his students create a new brand? They (or someone around them) composed a creation narrative that was likely alien to anything that Leung Jan had ever heard. Why not simply hop on the Hung Gar or White Crane bandwagon? There may even have been some decent historical and stylistic justification for doing so and the school may have achieved success more quickly.

Looking back at the history I suspect that the central issue was in fact social. One of the truly remarkable things about the Wing Chun Brand is its strong association with bourgeois and “new gentry” individuals during the early decade of the 20th century. Wing Chun instruction was prohibitively expensive between 1900 and the 1920s. The style mostly appealed to the educated children of landlords and business owners. This stands in sharp contrast to most other Chinese martial arts which were resolutely plebeian.

Most members of the Hung Sing Institute were working class trades people who were employed in Foshan’s various shops and factories. Wing Chun, on the other hand, tended to be studied by the sons of the people who owned these businesses. There is a strong element of class stratification here, as there was in many areas of Foshan’s popular culture.

Chan Wah Shun inherited more than just a medical practice and boxing style from Leung Jan. He also inherited a position in society, a set of social associations and expectations. While it may have been possible to bridge the technical space between Wing Chun and the other large martial brands that were coming into being, it may not have been possible to close the same social and economic gaps. In reality the sorts of individuals who did Wing Chun were the same class of people being targeted by the more revolutionary rhetoric that was popular in a number of other local styles. In this case the most efficient solution was to form a new brand (Wing Chun) in reaction to the ongoing conversation and competition between other players in the local market.

Conclusion

You cannot really understand why Wing Chun is a separate art just by looking at its techniques, which in truth are similar to other things in the region. Nor do its creation myths solve the mystery. Those are likely a product of a 1930s marketing campaign and are remarkably similar to other stories told in the Hung Gar and White Crane traditions. Instead it is necessary to look at the shape of the local market for hand combat instruction at the turn of the century, and then to ask how Chan Wah Shun, and the other major players, fit into that picture.

It quickly becomes clear that teaching the martial arts was a commercial, monetized, activity in most areas of the Pearl River Delta from the mid-19th century onward. This competition was shaped by the existence of a robust market for printed popular culture materials. By the 1920’s pretty much everyone was first exposed to the martial arts through these novels, articles, radio programs and even news reels. Of course opera and street performance (which might be thought of as earlier forms of “media”) also remained popular.

The various Chinese fighting styles were not transformed into “brands” by their encounter with late 20th century globalization. On a fundamental level they have always been brands. The traditional arts as we know them (basically from the 19th century onward) have always been concerned with marketing, product differentiation and image control. This is a natural consequence of the fact that they are the product of market transactions. It was the spread of markets that actually opened the social space that these fighting techniques needed to find new students, grow and thrive.

These market and advertising pressures have in turn influenced the way the Chinese martial arts developed. Fighting styles that were close to major trade and cultural centers were relatively privileged. They grew into some of the first, and most successful brands. Meanwhile smaller village and family styles in the countryside withered and died.

Teachers of smaller arts who wished to continue in the business were faced with a rather limited number of choices. Create their own competing public brands, join a different organization that was already economically successful or appropriate someone else’s brand. Social and economic factors, in addition to purely martial ones, seem to be an important element in determining which of these strategies was adopted. In conclusion, while there are clearly limitations to this approach (as there are to any) we can solve a number of important dilemmas by thinking about the traditional arts as competing brands rather than purely historically given social institutions.

oOo

If you enjoyed this post you might also want to read: Zhang Sanfeng: Political Ideology, Myth Making and the Great Taijiquan Debate

oOo

Leave a comment