Introduction

Dr. Yang Jwing-Ming generously sat down with Kung Fu Tea for a lengthy and wide ranging discussion of his martial arts experiences in both Taiwan and the United States. A major topic of conversation was the creation of YMAA Publications which remains one of the most important martial arts publishing houses. Also intriguing were Dr. Yang’s thoughts on the future direction of the Chinese martial arts and the role that they might play as modern societies continue to grapple with the disruption of labor markets by the rapid development of artificial intelligence and automation. The notes from that interview have been edited for length and clarity.

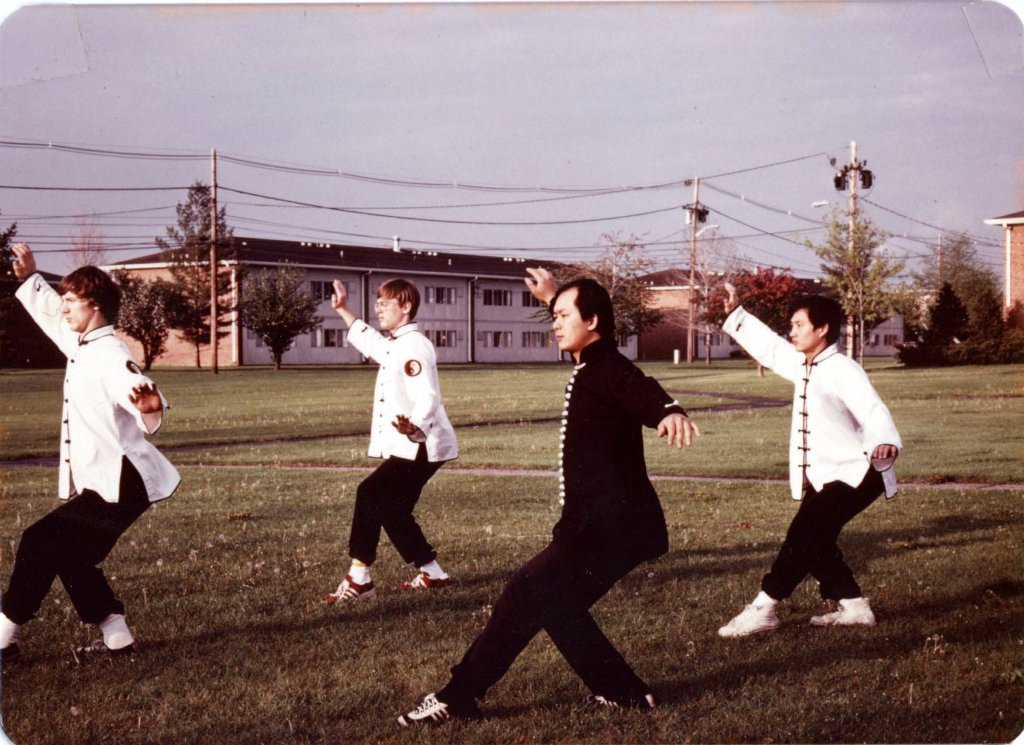

By way of introduction, Dr. Yang started his martial arts training at the age of fifteen under white crane Master Cheng Gin Gsao (曾金灶). The following year Dr. Yang began the study of Yang style taijiquan with Master Kao, Tao (高濤). He studied physics at Tamkang College in Taipei Xian and also began to practice Shaolin long fist with Master Li, Mao-Ching at the Tamkang College Guoshu Club (1964-1968). In 1971 Dr. Yang completed his M.S. degree in Physics at the National Taiwan University before serving in the Chinese Air Force from 1971 to 1972. In 1978 he completed his Doctorate in Mechanical Engineering at Perdue University in the United States. In 1984, Dr. Yang retired from his engineering career and undertook his life-long dream of teaching and researching the Chinese arts and introducing them to the West through his numerous books and publications.

oOo

Kung Fu Tea (KFT): I understand that as a youth in Taiwan you studied white crane, taijiquan and then Shaolin long fist while at university. What do you think inspired your interest in the martial arts as a teenager? Why, in your opinion, are we generally seeing less interest among young people in the traditional Chinese martial arts today?

Dr. Yang Jwing-Ming (YJM): First off, you have to understand what it was like in Taiwan in the 1960s. Military education was compulsory. When you became a teenager, they took you out and taught you how to shoot an M1 rifle and everyone was getting ready to fight the Chinese Communist army in a continuation of the civil war. And to actually fight the Chinese Communists was to die! As a result, many young people were trying to build up their inner courage, or just process their own mortality. They wanted to prove that they were brave. This led some people to fight or join gangs, and others studied martial arts.

When I first asked my parents about studying the martial arts, I was surprised that my father quickly said yes because some people used martial arts in gang activities. When I asked my grandmother about this she explained that we were from a martial arts village. In Yang village, before the war, everyone studied martial arts. It was a simple family style for farmers. The number of techniques was limited but people really perfected them.

Everything is different today. We haven’t had society wide wars in a long time. Young people are not scared or thinking about their own mortality. It was after the Vietnam War that martial arts really became popular in the United States. There was such an explosion of interest in the early 1970s. I remember watching Kung Fu with David Carradine and thinking that the martial arts choreography was not great, but at least people were really trying to explore a philosophy, which was good.

All of that changed in the 1980s. There came to be so much violence in all of the media about martial arts. There was also an increasing emphasis on how things looked rather than actual technique or application. The Chinese martial arts became like plastic flowers, a societal fashion rather than a pursuit of serious self-cultivation. “Gongfu” means time and energy, but most people have so little patience today.

Can you tell us a little more about what it was like to study in Taiwan? For instance, how did the training or instructional methods you experienced vary between a relatively traditional and southern art like white crane and the northern shaolin long fist your encountered later?

I started off studying white crane, which is a southern art. It has very strong hands. My white crane teacher was a farmer and he was like a father to me. In those days everything was a “secret,” very traditional.

It was also a matter of lifestyle. People had a life in ways that most do not today. I still have many friends who are engineers and all they do is go to work, come home exhausted, eat, go to sleep, and do it all over again the next day. They work like that for forty years and then, when they are 60, their company fires them because they can hire two younger engineers for the same salary.

I once asked my white crane teacher, how much time does it actually take to irrigate and tend your crops? He thought about it and said that except for planting and harvesting seasons, it generally took about two hours a day. The rest of the time he trained his martial arts, practiced musical instruments or chatted with friends. People in that environment had a life.

Because of famine and poor nutrition as a child I developed an ulcer and I suffered from them as a teenager. One day I had an attack in class with lots of pain. I turned pale and had to sit down. My teacher took my pulse and said “You have something wrong with your stomach” and then he told me that I had his permission to study taijiquan as that would help. People always wondered why a young kid like me studied taijiquan when, fundamentally, I loved to run and jump. Taijiquan is an internal art, and as I learned to focus on (and feel) my organs the ulcers improved. I am still free of them today.

Finally, I learned the long fist in a university club, and a club environment is very different. I had a friend who studied long fist and I was amazed at how fast his kicks were. He had all of this reach with his legs, but if I could get in close, I had the advantage in boxing. After grabbing a room and just fighting with him for five or six days I asked him to teach me long fist. He asked why he should teach me when we could just invite his master? After that we invited his teacher and started a club.

1928, and the formation of the Nanking Central Guoshu Institute, is a very important year for the Chinese martial arts. I often wonder how the Chinese martial arts would have developed if the Japanese had not attacked. After 1928, and the war with Japan, all of the martial artists were military men. And many of them came to Taiwan. Both my taijiquan and long fist masters were military men and discipline was central to their instructional style. They were like commanders. There were over a hundred students at the first day of the long fist club. At the next meeting only 36 came back. When we graduated only six of us were left. But that was typical.

In all of my martial arts training I never paid a penny. Not to my white crane teacher, or anyone else. No money was involved. This means that the groups of students being taught were generally small. If my white crane teacher didn’t like your character, he just wouldn’t teach you.

As for the future, I think this is going to be spiritual century. Our lives are regimented by schedules and regimes that are all the product of the industrial revolution and the last century. We are all stuck in that matrix. Yet we are approaching a time when artificial intelligence and robots are going to start to take over a huge number of jobs. But the one thing they can’t do is anything having to do with human feelings. It is like a pendulum that has swung in one direction, towards the external or violent, and is now swinging back towards the internal and spiritual. For instance, there is so much more interest in learning Qigong now than there was even ten years ago.

You formed YMAA publishing in 1984, which makes you one of the pioneers of martial arts publishing in the West. When you arrived in the United States for your doctoral work at Purdue, what was your impression of the sorts of martial arts media (books, magazine, TV programs) that you encountered?

I wasn’t impressed. There was so much interest in the martial arts, it was everywhere in the media, which I guess was good. But it had spread too fast and the American public’s understanding of it was shallow. It was clear that people were making money off of the martial arts, but they weren’t conveying the applications or philosophy.

When I first came to America to attend Purdue I had three stops. It was cheaper in those days to fly with three layovers. I stopped first in Los Angeles and then San Francisco. Everywhere I went I found some martial arts schools. At that point you had to pay a dollar just to observe a martial arts class. I paid my dollar and I watched what was going on and I said, “that is not a martial art,” there was no actual application. It was just a martial dance.

Again, gongfu is time and energy, you can’t rush it. Most arts, with the exceptions of things like xingyi quan, were developed or cultivated in monasteries. As such they have an emphasis on self-cultivation and self-defense. They weren’t directly used on battlefields and this gives them their unique character. But America, especially as you moved into the 1980s, had a fast-food culture. I still have people who come to the retreat center and in six lessons they want to become a Jedi. I am sorry, you can’t do that.

Chinese martial arts are a complex subject with deep theories that have developed over thousands of years. In that sense they are like classical music. Nuance and background are key to project. But again, who listens to classical music today? Who has the patience for it? I look and I can’t even find a classical channel on the radio. Instead of deep exploration there is an emphasis on appearance or fads, it is like picking up a flower and discovering that its plastic.

Why did you decide that it was necessary to create your own publishing company at that point in time?

I thought it was the best way to correct some of the issues that I had observed with the Chinese martial arts in America. I thought that by publishing books I could redirect the general public onto a better path. Every movement in these systems has its deeper meaning and applications. Application, in particular, take time and energy to become instinctive reflexes.

What I saw was that due to commercial pressures, where the martial arts had become a business, the standards were being downgraded. Teachers and students had basically switched roles. In Taiwan it was about discipline. But now students were the masters because they paid the fees, and teachers had become businessmen who provided whatever the students demanded.

There were other problems as well. I actually published my first four books with Unique Publications. But they kept demanding changes, basically taking all of the philosophy or deeper discussion out of the books and turning them into shallow technical manuals, because they thought that this was what excited consumers. Everything was for business rather than actual education. They even tried to change the way I wrote. But I wanted to write in a way that would help people to understand what was real in the traditional martial arts.

What were some of the major challenges that you faced in the early days of publishing martial arts books?

There were so many challenges! People think that the creation of YMAA was a single smooth ascent but in fact there were repeated setbacks. The first challenge would have to be a total lack of money. When I came to the United States, I literally had nothing.

I was working alone in 1984 because I could not afford to hire editors, typesetters, photographers or anyone else. I had to learn how to do my own photography, and I took a course in typesetting at Harvard. There were not word processers then, so “cutting and pasting” was a very literal thing. And I didn’t have any experience in marketing books.

Then one of my students, David Ripianzi, came along and said “Let me help.” I asked how he could do that as he was a college student. David responded that he didn’t really like college, so we got to work.

How has the advent social media (YouTube, Facebook, etc.) effected the market for martial arts material? How has YMAA adjusted to this shifting landscape?

I sold the publication company to David about 15 years ago now, so we would have to bring him into the conversation to get his answer on that. At the time there was still no YouTube or Facebook, etc. We had regular mail for distribution, telephones and advertisement through martial arts magazine. Later on we also advertised through book distributors. Everything is so different now. But I guess I was lucky to get out when the market was still in a good place.

I think it is impossible to discuss any aspect of martial arts right now and not reflect on the impact that COVID-19 is having on our community. How have your teaching, travel and publishing activities been affected by the current situation?

It is very unfortunate. I don’t have a regular school like other teachers, but we still had to cancel all of the events and seminars at our retreat center here in California. There is not much travel and we can’t bring anyone here right now. And of course, I can’t travel for seminars in other places. At the moment we are getting zero income from these traditional sources.

Fortunately, my disciples Jonathan and Michelle have been able to set up some webinars. These have been surprisingly successful, and they do bring in income, but not at the same level as before. There are just limits to how many little screens you can keep track of at one time.

Still, as someone in my 70s there are other aspects of the current situation that may not be so bad. I have had time to focus on my writing, which is something that I have wanted to do. I have also been working on my meditation. I have even started to learn how to play some musical instruments that I have always dreamed of playing. Ironically, it feels a bit like I finally have my life back.

One of the things that I have noticed watching on-line discussions since the start of this crisis is that taolu, which many individuals in the combat sports community had been telling us was very problematic for years, is getting a second look in the current era of solo training and social distancing. Given the controversies that have surrounded the TCMA in recent years, what do you see as the major benefits of taolu and other forms of solo practice?

The main value of taolu, or “sequences” as I tend to call them, is to give people a chance to develop the strength and reflexes (and muscle memory) to do certain things. In the traditional martial arts we train everyone to be a teacher. So your taolu functions as deep library of knowledge that acts as a curriculum for the preservation of the entire system. Everything is in there.

Of course, most people can really only specialize in a few things that they are well suited to. Look at modern martial arts like Thai kickboxing. They are amazing because they take a limited number of skills and really perfect them! There is so much depth in taolu that no one can really specialize in all of it, but it is the key to passing on the system. At the same time, you have to choose the things that you as a student will specialize in. One of the issues that I see is that students spend all of their time “learning,” but not training, and as a result they can’t fight. So I tell people to just focus on a few of the more practical ones.

Obviously, all kinds of schools are scrambling to adjust their teaching methods and programs to survive in the current era. Do you think that any of the changes that we are seeing in the face of COVID-19 are likely to have a long-term impact on the traditional Chinese martial arts are taught and practiced (at least in the North American marketplace)?

I don’t think that most martial artists realize how fundamental the changes already are at this point. If there is a positive side to the current tragedy, it is that by really causing pain it is forcing us to evolve. Humans don’t react, they don’t change or evolve, without pain. It is when we are trapped that we start looking for new solutions.

For instance, webinars will continue to be popular in ways that they were not in the past. Here are a couple of reasons why. Students have discovered that they actually can learn from home. And given the time constraints that everyone is under, the realization that you may not have to constantly travel is an important one. Likewise, instructors have learned that they can now reach a global audience, effectively expanding their network of students, without all of the time and expense that was involved in traveling between America and Europe or Asia. Basically, we have discovered that more training can be done remotely, with occasional in-person visits (a couple of times a year), than we had previously guessed.

Not all instructors or schools will benefit from this new system. I can give webinars because of my books and other publications. I always told other teachers that they needed to publish. Now, if you haven’t, it is very hard to attract that global audience. But all sorts of remote learning will become more popular. And with people’s increasingly fragmented schedules they can even follow along when it works for them.

While reviewing your bibliography I noticed that you during your academic career you always seems to have been pursuing dual tracks. On the one hand you taught and studies physics, but at the same time you also taught and studied martial arts (sometimes as a course for university credit). Given that Kung Fu Tea is basically a blog about the academic study of martial arts, I was wondering whether you see universities as having a role in the promotion and preservation of global martial arts movements? If so, what is it?

There are already many universities in Asia that do this. In China and Taiwan we commonly see wushu departments, which works because wushu can be practiced as a traditional art, but also as a very effective and popular sport. Like any other art (painting, classical music, etc.) there has to be some mechanism to pass it down through the years. And if you can emphasize the philosophy, or the history of the martial arts, universities can play a role.

Today, it is widely recognized that learning traditional martial arts can help a student develop their self-discipline and cultivate higher levels of alertness and awareness. Those are important attributes. However, the greatest benefits that traditional martial arts (especially the internal ones) can bestow is long-term mental and physical health.

One of the exciting developments in the last ten years has been the creation of a robust interdisciplinary research area dedicated to the study of martial arts and combat sports in European and North American Universities. A lot of the work currently being produced focuses on the sociology, culture and history of martial arts communities and practices. What aspects of the Chinese martial arts do you feel could benefit from more scholarly engagement? If you could suggest a title for scholarly book or article on some aspect of the TCMA that you would really want to read, what would it be?

First off, I am very excited to hear more people are starting to take martial arts seriously. Too often since the 1980s these things have been understood in a very shallow way. Chinese martial arts have been practiced for thousands of years. Again, I see it as similar to classical music. Existing ancient documents and skills passed down from those experienced martial arts teachers are precious. That is why I always translate these documents and interpret them. I hope that through this effort, I am able to bring back public interest in researching the deep theoretical aspect of martial arts. Manuals that were produced during the Republic period (especially the 1920s and 1930s) are especially important for understanding the Chinese martial arts, but there has not been much interest in them.

The theory and techniques that developed in today’s martial society are built upon on today’s mentality and social goals. Older traditional arts that have been developed through thousand years with real battle experience were often more practical. For example, sparring in today’s tournaments is not the same as a real-life situation. When you are in a life and death situation, your mental and physical responses are different. Since we don’t have the same environment, or face the same violence, it is not easy to create martial arts that reaches the same level.

What are the goals of Chinese martial culture or martial society? What were the traditional martial arts really trying to cultivate? First bravery, second power, third gongfu (in the traditional sense of the term). Or to put it slightly differently; first, speed; second, power; third, proper techniques.

In terms of the books that I would want to see, I think maybe a comparative collection and study of translations of some of the Chinese martial arts classics which lay this foundation.

Thank you so much for stopping by Kung Fu Tea and sharing your insights on the nature and the development of the Chinese Martial Arts. Readers interesting in further exploring Dr. Yang’s teaching may wish to check out any one of his many publications including Tai Chi Push Hands: The Martial Foundation of Tai Chi Chuan, with David W. Grantham, and Tai Chi Secrets of the Yang Style—Chinese Classics, Translations, Commentary.

December 20, 2020 at 5:46 pm

What a fantastic interview by a thoughtful and intelligent Master of the arts. Dr Yang deals with the balance between martial arts as a practical art versus the studying for personal cultivation and understanding. Modern society is not like ancient times and while I have grappled with TaiChi being effective for survival, but in honesty it is less necessary for modern society! TaiChi is a beautiful art that Dr Yang infuses with its real martial character and if you truly study it, there is plenty of practical defences and attacks there. Thankyou Dr Yang, for your lifetime of dedication, love and scholarship on these important arts!

December 21, 2020 at 7:57 am

Very well said. Greetings from Poland