***Its my birthday! To celebrate we are taking a second look at an early photograph with one of my favorite pictures of a Japanese samurai. And essay that comes with it is decent as well. Enjoy!***

Giving Up the Gun: Revisiting a Classic Argument.

In 1979 a Dartmouth English Professor named Neol Perrin wrote one of the more popular and more widely read books on the history of the martial arts. It was titled Giving Up the Gun: Japan’s Reversion to the Sword, 1543-1879. While a non-specialist, and more interested in Japanese literature than military history, the book gained quite a following. I first encountered it in high school after I developed a fascination with the Japanese sword arts. While so many of my classmates were delving into the dark secrets of Ninjitsu, I was more interested in understanding why there was an entire island full of warriors who carried swords rather than guns until the second half of the 19th century. Apparently students of martial studies are born rather than made.

Professor Perrin shared my curiosity on the subject. Or maybe not. To the great chagrin of historians everywhere, sometimes people with very little interest in their stated subject matter write historical books anyway. Perrin was actually interested in something much more contemporary. The true focus of his slim volume, published at the absolute nadir of the Cold War, was nuclear disarmament. Could the developed states of the world dismantle their high-tech arsenals and slow the pace of proliferation? At the time it seemed to be the only question worth asking.

The Japanese were an interesting test-case for Perrin. The establishment of the Tokugawa Shogunate had been a long, bloody and uncertain process. Further, it was an affair that swords played relatively little role in. They had not really dominated the Japanese battlefield for hundreds of years. As the size and technical sophistication of the Japanese feudal armies increased the sword and bow were replaced with the spear (yari) and the matchlock. Firearms, both in the guise of matchlock rifles and cannons (some of them quite large) were the key to the ultimate establishment of the new government.

Much of this technology was quite sophisticated. The Japanese got so good at copying western weapons that they were able to modify the designs and even begin to export these arms to other, less technically advanced, buyers. They developed devices to allow groups of gunners to engage in accurate mass fire at night (an important skill before the invention of the heavy machine gun), and they learned all sorts of lessons about how gunpowder changed the battlefield.

Then everything changed. Once in power the new government closed the doors to social mobility and fossilized the class system. The peasants were systematically disarmed, which was an important event as networks of religiously motivated peasant revolutionaries had been one of the groups to most successfully employ guns on the battlefield. Even the samurai ceased to carry firearms in public. For that matter the three meter spear, which had dominated the battlefield for hundreds of years, slipped into obscurity and was nearly forgotten by all but the most esoteric martial arts schools. Instead there was renewed interest in the cult of the sword.

It was only in this late period that the sword became the “soul of the samurai.” Prior to that top honors had gone to the bow, the spear and, very briefly, the gun. Even contemporary sword masters realized that their weapon was obsolete on the “modern” battlefield of the 17th century. At best it was a weapon of personal defense if you were unhorsed or your spear was lost. Yet it is the sword that dominates the last era of Japanese feudal history.

Nor was this seeming loss of military technology mirrored in other areas of Japanese society. While isolated from much of the world the Japanese did attempt to keep up on medical and scientific developments through their limited contacts with the west. I have always been under the impression that standards of living were pretty high in Japan compared to some of the more marginal areas of southern China that I have studied, though I would need to look at some actual economic data to know for sure.

For Perrin this was the crux of the issue. The Japanese were not forced to give up the gun by foreign domination, or social and technological decay. It is easy to understand the loss of technology through these sorts of processes. Instead they (meaning the political and cultural elite) made a choice to take one sort of military technology and put it back on the shelf.

This was an unprecedented moment in human history and Perrin wanted to know whether it could act as a model of nuclear disarmament. Many of the critics of his work have fundamentally misunderstood his project. He was not an English professor pretending to be a historian, and hence writing bad history. He was actually an English professor pretending to be a social scientist. Perrin’s real aim was to talk about causality. He wanted to develop a covering law that explained disarmament, and he did so through a single, highly detailed, case study.

Japanese historians quickly pointed out that the Samurai never actually gave up the gun in any definitive sense. They continued to maintain some coastal batteries and individual Lords maintained stockpiles of these weapons. There were even periodic reminders by the Shogunate that all Lords were required by law to maintain large number of muskets and insure that their troops were drilled in using them, should the need should ever arise. Pretty much the only group in Japanese society that lost its connection with firearms was the peasantry, but this relationship was not so much “given up” as “forcibly severed” as part of the maintenance of an absolutely brutal class based feudal system.

Many historians have been quick to dismiss Perrin. He wants to talk about variables like “culture” and “choice,” where as they turn to “realist” political analysis. The Japanese turned away from the gun because after the establishment of the new government the state entered a period of peace that lasted for 200 years. Weapons development is expensive and socially disruptive. No one does it just because it is fun. Countries do it because they are forced to over the course of certain types of conflicts.

The development of firearms exploded in Europe between 1650 and 1850 not because the west was more rational, more scientific or more technologically advanced. The real reasons were purely political. This was a period of almost continual warfare and violent conflict.

According to this realpolitik view, weapons development happens only when it is rational to do so. War accelerates this process. During times of peace there are other spending priorities that will better insure your hold on power, such as public works or infrastructure spending, so this is where rulers will spend their gold. (For any international relations scholars out there that are keeping score, what I have just described is a “classical realist” theory rather than a stricter “neo-realist” account).

China: The Dragon and the Gun.

It is interesting to consider what happens when we bring China into this discussion. China has a somewhat schizophrenic reputation on this point. On the one hand it is credited with the invention of gun powder and the rocket, two of the more important destructive technologies of all time. On the other hand it is burdened with images of peasant soldiers, armed only with spears, running into the face of machine gun-fire as late as the Korean War.

Rather than these being treated as isolated incidents that were the result of process failures in society’s military/industrial complex, these instances are often taken as being indicative of something about Chinese culture and its values. It is often said that the Chinese do not value “human life.” I have even had some of my own Chinese graduate students tell me this when trying to explain some of the more puzzling points of state policy. Yet I cannot help but notice that all of the Chinese individuals who I associate with do value human life. It is always some other mysterious person, who no one can quite identify, that lacks any humanity. This should be a warning flag to those seeking to advance historical arguments based on cultural difference. I am not saying that culture is never important, but this is a variable that needs to be employed with great caution. Desperation makes people do “desperate” things, but that is not really the same as proving that they have fundamentally different values.

The 19th century European view was, if anything, more reductionist. They explained their world in terms of racial categories. In their view the Chinese lacked the mental or moral capacity to master the modern arts of warfare. And yet these arguments always rang hollow, even to the individuals who advanced them. The fact that it was the Chinese who initially created this entire class of weapons could not be forgotten. Nor could the Europeans afford to overlook the furious pace of Chinese military advance.

In the 1850s Guangzhou found itself badly outgunned against the British. By 1911 everything was different. China was awash in modern European weapons and highly trained military specialists. The state was militarily just as advanced as most European states. Its defeats in the early 20th century had more to do with political divisions and a lack of unity than any actual military factors. This means that in only 50 years China was able to radically transform not just their military arms, but the entire social and military structure that produced and supported them. It had taken all of Europe nearly 200 years to complete this same transformation. Clearly the Chinese reformers were quite talented. One of the problems with the “victimization” narrative promoted by the Chinese state today is that causes individuals, in both the east and west, to systematically overlook these accomplishments.

I suspect that the success of the traditional Chinese martial arts may actually account for much of the historical misunderstanding that goes on. For better or worse, Kung Fu has become a critical part of China’s public diplomacy. These unarmed fighting systems seem philosophically rich and purely defensive. I suspect that this perception has helped to ease tensions about China’s growing influence in the world. But on the other hand, the same whiff of ancient mysticism makes these arts appear to be fundamentally incompatible with the modern world.

The supremacy of the gun over the more physical disciplines of combat is too firmly entrenched in the western mind to be easily dismissed. It is a message that our media has reinforced repeatedly throughout the 20th century. From cowboys exterminating Indians, to Indian Jones carelessly blowing away a Middle Eastern swordsman, we are confident in our ability to negotiate a hostile world. The superiority of the gun seems to reinforce our broader faith in technology.

Nor is the American media alone in this assessment. If anything Chinese story tellers have been even more enthusiastic in linking the gun to the “modern” world. In western science fiction we can at least find a place for hand combat, whether it is Luke’s transformation into a disciplined Jedi knight, or Captain Kirk forgoing the niceties of the phaser for the simple pleasures of beating down a malicious alien with his own bare hands.

I have never run across anything quite like a Jedi knight in the Kung Fu genera. Instead the vast majority of Kung Fu stories tend to be backwards looking. They look back to a simpler time before the coming of the gun, when more “civilized” methods of defense still held sway. They paint a picture of a reassuring world where ultimate power went to the individual who worked the hardest, who developed the best Kung Fu, rather than to gangster who could buy the most guns. In the popular imagination Kung Fu is as much about justice as it is anything else.

I literally cannot count the number of martial arts films that I have seen which revolve around the introduction of firearms and how they destroy the “old order” of things. Inevitably the hero beats the bad guy with the gun one last time, but the writing is on the wall. The age of hand combat is drawing to a close. In the “age of the gun” there is simply no way to defend yourself with your hands. In fact, there is no way for the individual to defend himself against the industrialized aspect of society.

I despise this narrative. It is not just that it gets the actual history of Chinese martial arts wrong, but it creates a vision of an unreal past. Once you have internalized this vision it becomes impossible to understand the true history of Kung Fu even if someone stops to explain it to you.

It is a powerful narrative because it speaks to a lost “golden age” that has just slipped out of our grasp. It captures the sorts of struggles that individuals feel in their own lives. This is the story of a world that is passing you by. Unfortunately it is now the only version of 19th century history that most individuals in China are familiar with. If you ask them about the martial arts they will all tell, first we used traditional hand combat, then guns came and we modernized.

Historically speaking, this is totally backwards. First the guns came, and then the modern martial arts developed. What we see in China is quite similar to the puzzle that made life difficult for Perrin when he discussed Japan.

Firearms have been a fact of life in China since the 1300s. At first they were difficult and expensive to manufacture, but the government employed large numbers of hand cannons, field artillery pieces and even massive rocket launchers from an early period. If you are curious about what early military gunnery looked like you should check out the Fire Dragon Manual. At the start of the Ming dynasty Chinese firearms were probably the most advanced in the world. So what happened?

Well, the Ming dynasty was a success, at least for a while. After a few decades of peace, and with no real systemic threats on the horizon, it makes a lot more sense to keep taxes low, invest in your infrastructure and protect against famine (preventing peasant uprisings) than it does to invest in new firearms technology. The Ming state was not even willing to maintain a standing peacetime army.

Of course the logic of this situation changed again during the Ming-Qing cataclysm. When things start to fall apart, both the forces of order and disorder suddenly become much more interested in the latest European advances in firearms technology. Matchlocks become a necessary part of any well-appointed army.

By the 1580s this upswing in the use of firearms was well underway. Of course this is also when unarmed boxing, mixed with philosophy and medicine, starts to gain popularity at Shaolin. In short, it was the decade when the idea of the modern Chinese martial arts really took root. For the rest of Ming dynasty the more militarily relevant pole fighting forms continued to dominate life at the Temple. But by early in the Qing, the ascendency of unarmed boxing was complete.

The Qing dynasty starts off following the same pattern. The Qing know about firearms and use them in their wars of expansion. However, as the kingdom entered a period of peace technological developments in this field are placed on hold. Like the Japanese they knew about the development of flintlock weapons, but they chose not to invest in the new technology. Investment in firearms did not really explode until the Taiping Rebellion forced a massive reevaluation of the military situation.

The Qing were always more afraid of domestic civil war than foreign invasion and the Taiping Rebellion, which claimed 20 million lives, nicely illustrates why. This catastrophic intra-state conflict is also interesting in that it happened at roughly the same time as the American Civil War. Where the Civil War is often called the “first modern war” because of its use of rifled bullets, repeating weapons and trenches, the Taiping Rebellion is called the “last traditional war” because of its heavy reliance on spears, bows and swords.

Of course that is not the whole story. The ill equipped Imperial military started off armed mostly with cold weapons and a smattering of ancient matchlocks. But the more modern, smaller, privately funded Gentry militias that arose by the end of the war looked much different. They were armed with state of the art European muskets, modern uniforms and mobile field artillery. In short, the Chinese military at the start of the Taiping rebellion may have looked distinctly medieval, but by the end of that conflict they looked remarkably like the units that fought in the American Civil War. This was a decade of rapid transformation.

When the west did invade China during the final stages of the Boxer Uprising they found, much to their surprise, an Imperial army armed with modern rifles, machine guns and artillery. Social and political factors undercut the efficiency of these units and led to their defeat. But by 1900 China had clearly demonstrated the ability to field an modern army.

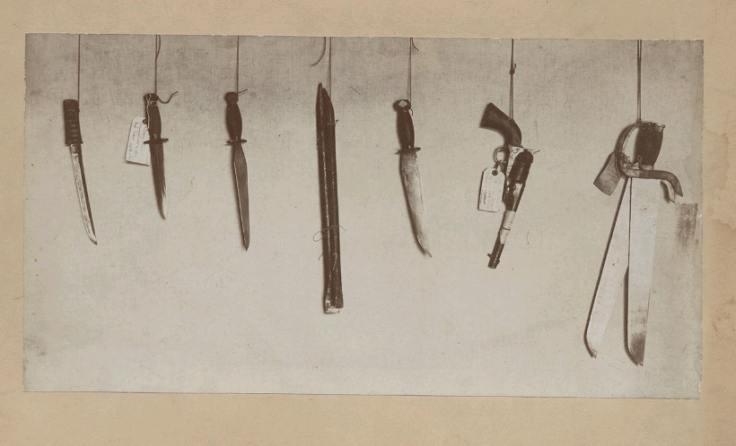

Nor were these developments restricted to the military. By the end of the Qing Chinese bandits had traded their swords for rifles, but otherwise carried on in the traditional manner. Even earlier Armed Escort companies had started to arm their guards (all of whom were high trained martial artists) with carbines and hand guns. In fact, the most popular weapon in late 19th century China was a Colt cap and ball revolver. This is exactly the same weapon that “won the west” in America.

It is true that the average Chinese citizen did not own any firearms, and it is doubtful that most peasants could afford them. But that did not stop specialists in violence from getting their hands on modern firearms. By the late 19th century the “Rivers and Lakes” of China were awash in guns.

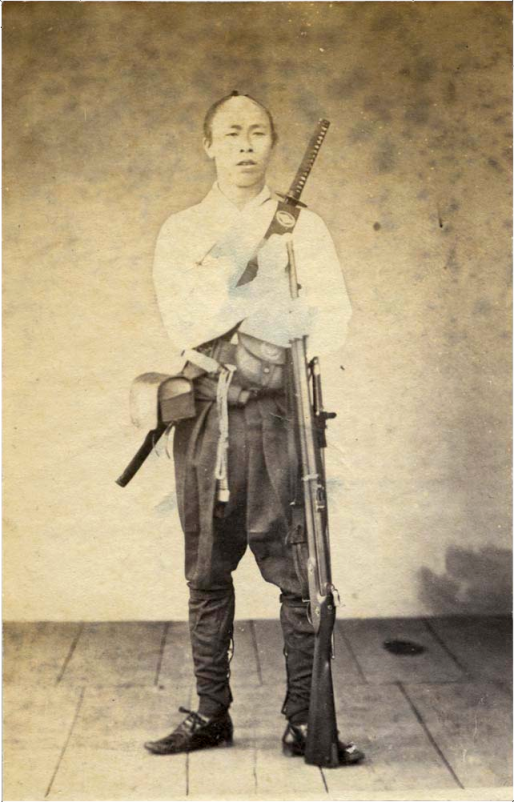

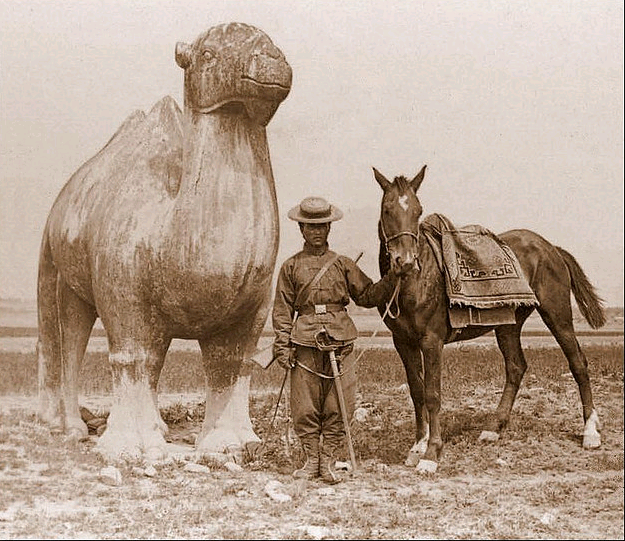

Period photos are quite interesting. They show a number of different types of weapons existing and in use at the same time. Traditional swords have not vanished and obsolete Qing matchlocks all exist side by side with modern handguns and rifles. Caravan guards would make a point of carrying highly visible traditional weapons and less flash (but very practical) modern ones.

This is the world that Kung Fu evolved in. It had its roots in the late Ming, an era that saw the heavy use of firearms, and it reached its full flowering in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, another era in which the use of guns was routine. Again, we need to remember that most martial arts styles are not as ancient as they claim to be. Most of them date to exactly this period.

Further, many of these modern styles are also very practical. Choy Li Fut, Pakmie and Wing Chun all saw themselves as primarily self-defense arts. They were created in dangerous urban environments dominated by organized crime and drug smuggling. Handguns and knives were common, yet there was a perceived need for additional self-defense tools.

This shouldn’t really be all that surprising. Combat happens at a variety of ranges, and sometimes you don’t have your gun or you cannot deploy it. That is why military units and police forces around the world tend to be at the forefront of hand combat training. Simply saying “I don’t need to know how to defend myself because I own a gun” is not really an option. The creators of the modern martial arts knew this, and unless you can integrate these arts into a world with guns you are not really fulfilling the vision of their founders. It is probably not an accident what while we don’t know much about Ip Man’s career as a police officer, the one story that is widely repeated has to do with him using his Wing Chun to defeat an individual who is attempting to point a gun at him.

On the other hand, the unarmed martial arts can create a feeling of confidence and well-being in a world where these things are in short supply. Daily life cannot stop during the 1930s just because society is slowly disintegrating. Practical combat skills aside, the traditional arts can give someone the confidence to walk down the street and go about their business when they might otherwise not have the courage to do it. As General Qi Jiguang observed, the role of boxing is to take the “weak” and make them “strong.” As often as not this is a psychological process.

In many ways, the modern southern Chinese martial arts and the gun are one. These are related phenomenon. They developed together. Yet you would never guess that listening to the storytelling and mythology surrounding the martial arts. At a couple of critical junctures in literary history a stylistic choice was made to exclude firearms from this mythos. The only possible exception seems to be to use them as symbolic coda to signal the end of a period of ‘Wude’ or martial virtue.

It is important to note that this stylistic choice was not inevitable. Water Margin, the ancestor of all modern Chinese martial arts stories, features a variety of non-heroic military weapons that require specialized training, including hooked spears and rockets. See for instance the stories surrounding the former military officer Ling Zhen. He is an expert in both gunnery and traditional archery, though his nickname “Heaven Shaking Thunder” leaves no doubt as to which skill was more popular with audiences.

I have not done enough research to actually verify this with certainty, but it seems to me that something changed in the sorts of Kung Fu stories that were told in southern China in the late 19th century. In reviewing Hamm’s discussion of “Old School Guangdong Fiction” I noticed that firearms had basically disappeared from all of these stories (see John Christopher Hamm. Paper Swordsman: Jin Yon and the Modern Martial Arts Novel. University of Hawaii Press. 2005. Pp 1-49). This was especially true of those stories that involved the Shaolin monks.

These characters are critical to the literary, cultural and ethnographic identity of the Southern martial arts practiced by the Cantonese speaking community of southern China. Ironically they don’t actually seem to have had any historical relationship with the local styles, except in the most tangential sense. Yet every Hung Mun Martial Art, and every Triad initial ceremony, traces its roots back to the mythological destruction of the Shaolin Temple in the 1720s. This single story is the central motif that organizes much of martial life on the “Rivers and Lakes” of southern China.

This same motif is picked up and enlarged in the important novel “Everlasting,” the direct precursor to Ip Man’s Wing Chun creation story. In this novel the Shaolin Monks find themselves in a surreal historical dream-scape in which southern China is struggling to maintain its independence from political and cultural authority in the north. That independence is safeguarded by the martial genius and bad tempers of the Shaolin Monks. Yet it is only a matter of time until the Qing manage to assert their modern military and social control over the region, dragging it into the realm of mundane history. Interestingly the Nun Ng Moy, who is later credited with the creation of Wing Chun, is portrayed as an instrument of Shaolin’s destruction and an ally to the Qing. She is not re-imagined as a heroine until the 1930s.

I don’t think it would be an exaggeration to say that in literary terms “Everlasting” is the most important Kung Fu story ever told. The completed work was published anonymously in the 1890s and it was very successful. Audiences could not get enough of it. It was massively plagiarized, borrowed from and expanded upon by early 20th century authors. Almost all modern “Shaolin folklore” in southern China traces its roots back to this one novel. This only serves to illustrate the point that while many martial arts disseminate themselves through an “oral framework,” one cannot ignore the broader literature of the period.

Most of what we imagine the “traditional” world of Kung Fu to have been is really a fictional construction. This vision is later than you might expect, and it draws on a relatively narrow range of sources. As a result there has been a natural “bottle-neck” in how we imagine and understand the Chinese martial arts. Ideas and themes that were common in the past went extinct if they were not included in “Everlasting” or one of half a dozen other stories that shape our modern view of Kung Fu.

I suspect that this is how we created and came to accept a theory of the past in which martial arts and firearms could not coexist. That vision of the world is historically flawed. There has never been a time in Chinese society after the 1300s in which firearms were not an important military technology. Their development may have slowed at some points, and accelerated at others, but this slowing cannot account for their near total absence from folklore and the popular imagination.

Courtesy the digital collection of the Bancroft Library, UC Berkley.

Conclusion: Martial Arts, the Community and the Myths we Tell.

This is where we must return to the ideas of Noel Perrin and his original argument. He noted that while the Tokugawa government could not technically forget about guns, they were able to choose what they wished to emphasize. They selected the sword and personal honor. They did this for both political and social reasons. As long as peace reigned in the land, it worked. “Choice” is a big part of what happened in Japan, and I think that his critics have unfairly played down and ignored this aspect of the story.

China presents an interesting alternative case. Conflict remained frequent enough that firearms could never actually disappear from the battlefield to the same extent that they did in Japan. They were constantly being hauled out of storage and dusted off for use in some corner of the empire. Both internal and external threats in the 19th century necessitated the rapid modernization of the nation’s firearms.

Yet the question of cultural choice never actually goes away. The “taste-makers” that mattered most in southern China were newspaper editors and book publishers, not the government in far off Beijing. Even though these individuals were living in a world awash in firearms, when they told Kung Fu stories they were able to choose to “forget” them. They constructed an alternate world where unarmed combat reigned supreme and victory went to the side that worked harder and sacrificed the most. Their efforts at mythmaking were so successful that most individuals in both the east and west today just assume that this is what 18th and 19th century actually looked like.

These literary actors were drives by cultural and aesthetic considerations, as well as brewing questions of regional and national identity. I suspect that each of these factors was at play in Japan as well. While realpolitik seems to determine when one invests money in weapons development, it has less to say about when those weapons will become part of the popular imagination and how they will affect the understanding of “security” within the state. These symbols are very much up for grabs and they may be shaped by either a centralized discourse (as we saw in Japan) or a decentralized market driven process (which emerged in southern China in the late 19th century).

Students of martial studies need to carefully separate and track the technical development of military innovation from the social stories that we tell about it. Rarely are these actually the same thing. Further, practicing students of the southern Chinese martial arts should remember that their styles never existed in an idyllic past. Firearms, knives and urban street crime have always been a part of their world. If you are not preparing your students to deal with these “modern” threats you are no longer teaching a “traditional” art.

December 14, 2020 at 3:00 am

Hi Ben

Very interesting article, many thanks – was just talking about this subject with some martial mates last week.

I don’t know where that biaoju photo was first published, but there was an original print of it on display at one of Pingyao’s bodyguard museums in 2007.

You might like attached pic in my collection – apologies, have no idea of date or where it’s from, just have a glass slide.

best

david ________________________________

December 17, 2020 at 9:55 am

Great article. I didn’t know that most of the martial arts had started in the late 19th and early 20th century