I was recently invited to contribute an article to a forthcoming volume on the history and development of Wing Chun. The catch was that it had to be less than five thousand words. I have literally written hundreds of thousands of words on this subject, so I knew that would be a challenge. Still, I am pretty happy with the way this turned out, and unless the publisher asks me to take this down, I am happy to share it with the readers of Kung Fu Tea!

Abstract

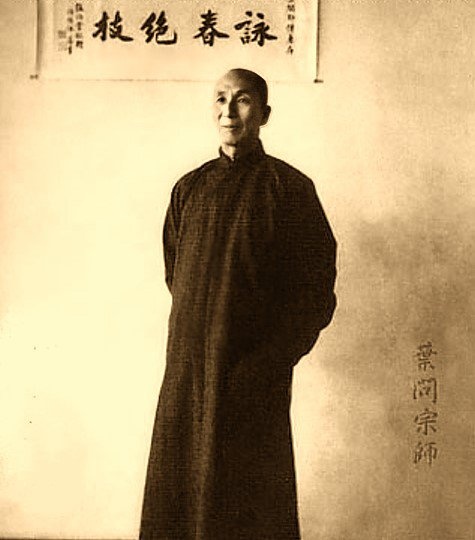

Wing Chun, as it is pronounced in its native Cantonese, or Yǒng Chūn (詠春) in Hanyu Pinyin, is a form of Southern Chinese hand combat first taught publicly in the Pearl River Delta region of Guangdong province during the second half of the 19th century. It slowly gained popularity in the area during the Republic Period (1911-1949), but declined dramatically on the mainland after 1949. It became a global phenomenon when Ip Man (1893-1972), a resident of Foshan and former police officer, moved to Hong Kong and began to teach professionally in the early 1950s. His best-known student, Bruce Lee, became the first Asian-American superstar in the early 1970s. Lee’s fame and efforts to promote the Chinese martial arts ensured that Wing Chun would become one of the most widely distributed and successful traditional fighting systems within the global marketplace. The art’s popularity was further boosted by the release of a series of fictionalized treatments of Ip Man’s life starting with Wilson Ip’s highly successful 2008 film Ip Man. Today the art enjoys great popularity not only in Hong Kong but throughout Oceana, the Americas, Europe and China where several lineages have been popularized or “rediscovered” in recent decades.

Key Words: Chinese Martial Arts, Wushu, Kung Fu, Bruce Lee, Ip Man, Wing Chun, Southern China

Introduction

Originally practiced by the Cantonese speaking population of the Pearl River Delta region, Wing Chun is a concept-based fighting system known for its distinct high stances, triangular footwork, short-range boxing and trapping techniques, emphasis on relaxation and preference for low kicks.[i] Most branches of the art feature three unarmed forms, Siu Lim Tao (the Little Idea, or Little Thought Form), Chum Kiu (Seeking Bridges) and Biu Ji (Thrusting Fingers). The most commonly encountered weapons are the Baat Jaam Do (Eight Directional Chopping/Slashing Knives, Wing Chun’s version of the hudiedao) and a single tailed fighting pole typically over three meters in length.[ii] These same weapons are often among the first taught in other regional Kung Fu styles, and were mainstays of the area’s 19th century militia system.[iii] Wing Chun is also known for its emphasis on wooden dummy (muk yan jong) training.

Distinctions in stance and technique are often noted between this system and the other arts which were popular in its hometown of Foshan including Choy Li Fut (the most popular art in the region through the late 1920s) and Hung Gar (also an important style in both Foshan and Guangzhou).[iv] It seems likely that Wing Chun developed in dialogue with these other modes of hand combat. It’s characteristic stances and triangular footwork bear a distinct resemblance to certain regional Hakka boxing styles and the arts of Fujian province.

This is not surprising as demographic pressures and market trends led to the emigration of large numbers of people (including many professional martial artists) from coastal Fujian to Guangdong throughout the 19th century. The market town of Foshan (a regionally critical trade center holding the imperial iron monopoly and known of its exports of silk, fine ceramics and a wide variety of handicraft goods)[v] was a popular destination for such immigrants. Foshan’s vibrant and quickly growing economy required security guards, civilian martial arts instructors, militia officers and popular entertainers. As such, the market town became a greenhouse nurturing the development of multiple martial arts styles.[vi]

The region’s contentious politics, including the Red Turban Revolt (1854-1856) and the First and Second Opium Wars (1839-1842, 1856-1860) meant that much of the male population was forced into militia service (or swept up in bandit armies) during the middle years of the 19th century. In this environment there was a great demand for skilled martial artists who could act as military trainers in the gentry led militia units, or who might be hired as mercenaries to stiffen the ranks of the imperial Green Standard Army which local officials viewed as understaffed and unreliable.[vii]

Following the end of these hostilities we see a period of innovation as martial artists sought to digest the lessons of the past and rebuild their lives. Douglas Wile has noted that the setbacks that China suffered at the hand of Western powers unleashed powerful internal discourses within the country as reformers sought for ways to preserve what was important within Chinese culture in an era characterized by rapid reform. Many of the Chinese martial arts most commonly seen today actually emerged, or were fundamentally reformulated, during this period of “self-strengthening.”[viii] This includes Wing Chun.

While many modern students attempt to parse it’s often fantastic folklore in an attempt to rediscover the ancient origins of the art, connecting the practice to migrants from Northern China (such as the Shaolin Monks) or regionally important culture heroes (including Cheung Ng),[ix] all of this ignores a fairly obvious point. The Wing Chun that is widely known and practiced today is not a particularly ancient practice. There is no reliable documentation of its existence, or that of any practitioners, prior to the mid 19th century. The art was not practiced widely until the Republic period (1910s-1940s), and many of the most popular schools today are reliant on changes made to the style’s pedagogy and presentation by Ip Man in the 1950s and 1960s. Wing Chun, like most Chinese martial arts, is a fundamentally modern practice and its nature can best be understood by examining the social history of Southern China between the closing years of the 19thcentury and the present.[x]

This does not suggest, however, that we can simply ignore the creation myths or oral history of the art. These texts are important as they provide us with insights into the social position and function of Wing Chun within a rapidly modernizing environment. Perhaps the oldest and most complete written version of the Wing Chun mythos was recorded by Ip Man in the 1960s for the creation of a proposed association that never came about. This account was found in his papers following his death and has subsequently been disseminated by the Hong Kong Ving Tsun Athletic Association (VTAA).[xi]

Briefly, Wing Chun, which might best be translated as ‘Beautiful Springtime’, was named not for its creator, the famous Shaolin nun Ng Moy, but rather its first student. After being forced to flee the provincial capital into the far West due to false accusations against her father, the teenaged Yim Wing Chun found herself the victim of unwanted marital advances by a local marketplace bully. Learning of the girls plight the nun Ng Moy (who had previously befriended the refugee family) revealed herself to be one of the five mythical survivors of the destruction of the Shaolin temple by the hated Qing.

Taking Wing Chun into the mountains, she trained her student in the Shaolin arts for a year. This allowed her young charge to defend her honor and defeat an individual who had terrorized the community. Leaving to resume her wandering, Ng Moy declared that this new art (which allowed the weak to defeat the strong) should be known by her student’s name. Yim Wing Chun was given the charge of passing on what she had learned, as well as resisting the Qing and working to restore the Ming.

Following that the myth becomes more genealogical in nature. It records that the art was transmitted to, and preserved by, a company of Cantonese opera performers in Foshan. Foshan was the home of the Cantonese Opera Guild prior to the Red Turban Revolt when the practice was officially suppressed. Eventually two of these individuals, Wong Wah Bo and Leung Yee Tai, would pass the art to a pharmacist in Foshan named Leung Jan. He would teach it to his children and a single student named Chan Wah Shun. Chan’s final disciple was the son of his landlord, a young Ip Man.

This entire account has a somewhat hybrid nature. Leung Jan, Chan Wah Shun and Ip Man are all known historical figures whose existence can be independently verified.[xii] However, the story’s opening acts are clearly fictional. All traditional Cantonese arts trace their origins to the survivors of the destruction of the Shaolin temple (a myth complex shared with the region’s Triads). However, historians have known for some time that the Qing never destroyed the Shaolin temple in Henan, and the Southern Shaolin temple (despite being “rediscovered” by multiple competing local governments) is more the product of literary creation than actual history.[xiii] Both Ng Moy and Yim Wing Chun seem to bear more than a passing resemblance to important female figures in the origin stories of certain branches of Fujianese White Crane. Indeed, it seems that this folklore impacted the development of Wing Chun, along with certain footwork patterns and stances.[xiv]

Christopher Hamm has published studies of the evolution of Southern China’s martial arts fiction during the late Qing and Republic period which can also help to date the Wing Chun myth. The story retold by Ip Man appears to be dependent on an anonymous novel, Shengchao Ding Sheng Wannian Qing (Everlasting), first published in 1893. This was one of the most popular martial arts novels sold in the region and it saw many reprinting and pirate editions. That is particularly important as in the original version of the story Ng Moy (who makes her first ever named appearance in these books) was not a hero. Rather she was an antagonist who conspired to bring down the Shaolin monks. She was not reimagined as a hero and friend of Shaolin until a pirate edition with an alternate ending titled Shaolin Xiao Yingxiong (Young Heroes from Shaolin) was published in the 1930s.[xv] The Wing Chun creation myth as related in the Ip Man lineage seems to be dependent on that relatively late edition.

Indeed, the openly revolutionary ideology of the story would also have been much more popular with readers in Republican China than with the subjects of the Qing dynasty who had to be quite careful about how they discussed the government. Yim Wing Chun is also interesting as she seems to act as a bridge pointing back to the possible influence of Fujianese boxing styles, while also connecting the art to popular trends in Republic era fiction that focused on stories of the amazing feats of female heroines. In short, while not a historical document, this story likely served an important role in explaining the nature and purpose of the art to Republic era students. It also supports the view that Wing Chun is a relatively recent art which may have first developed in the middle or later years of the 19th century (likely following the opera ban), before being popularized among Foshan’s middle class and bourgeois martial artists in the Republic period.

Wing Chun’s Development in the Republic Era

Setting aside questions of folk history, Wing Chun has passed through three subsequent evolutionary periods. It seems reasonable to assume that the preceding creation myth is correct in asserting that a set of practices and techniques were transmitted to Leung Jan by retired opera performers following the conclusion of the Red Turban Revolt. Being forced to find alternate modes of employment, it is not unlikely that some such individuals would have become private instructors for more wealthy families. Likewise, Chan Wah Shun is a historically attested individual who is known to have taught Wing Chun in the closing years of the Qing dynasty.

Still, the community practicing the art at this time would have been small. Many accounts suggest that Leung Jan (a successful medical practitioner) had no desire to teach publicly, instead passing his art only to his children and a single close family friend. Chan Wah Shun was active in a period when the martial arts were often viewed as a pathway to employment rather than as a means of recreation. Further, the high cost of his tuition ensured that his teachings were only available to well-to-do sons of local business owners. Ip Man later stated that his teacher had only 16 students over the course of his career and many of these were no longer teaching when he returned for college in Hong Kong. Even if we include the possibility of other related Wing Chun lineages during the late Qing, the total number of practitioners in and around Foshan was probably not more than a few dozen people.

It was only during the Republic Period (1911-1949) that Wing Chun became a fixture in the local martial arts landscape. This is not entirely unexpected as the waves of nationalist sentiment unleashed by the 1911 revolution helped to popularize practices like traditional boxing and wrestling. Further, educational reforms in the late 1910s and early 1920s led to a renewed emphasis on physical training throughout Chinese society and a number of groups argued that reformed and modernized martial arts practices should lead the way.[xvi] This social momentum fed the growth of all sorts of fighting arts at both the national and regional level. Wing Chun rode this wave of enthusiasm, really establishing itself in the Pearl River Delta region during the 1920s and 1930s.

Much of the folklore of the era focuses on the so called “Three Heroes of Wing Chun.” These individuals were Ip Man, Yuen Kay San and Yiu Choi. However, the “Three Heroes” label is misleading, being the product of later journalists seeking to write sensationalist accounts of local masters. In reality all three of these individuals did know each other, and they shared relatively privileged backgrounds. Ip Man’s family owned both land and businesses in Hong Kong and he never needed to work (dedicating his time to martial arts practice) until after the end of the Second World War.

Yuen Kay San (1887-1956) came from a family of industrialists who made their wealth through commercial pigments. His lineage history asserts that his father hired Fok Bo-Chuen and Fung Siu Ching, two students of another retired opera performer, Painted Face Kam, to teach his son. Yuen Kay San was known to associate with Ip Man and other Wing Chun practitioners at the school of Ng Chung So. But like Ip Man he never felt the necessity of running a school of his own.

Finally, Yiu Choi (1890-1956) was another son of a successful local businessman. He began his Wing Chun training under the tutelage of Yuen Kay San’s elder brother, before being recommended to Ng Chung So when the former moved to Vietnam. Like his well-off friends, Yiu also declined the role of teacher. However, he and his elder brother helped to finance the school where Ng Chung So taught and later looked after him in his retirement.

Given their wealth, visibility and social status it is not hard to imagine why writers and journalists would latch onto these individuals. Yet their actual contributions to the development of Wing Chun at this time were quite modest as they were not directly responsible for the instruction or training of many students.

The actual leading figures of the Wing Chun community at this time, and the two individuals responsible for training most of the instructors that one actually encounters in Republic period historical accounts, are Ng Chung So (one of Chan Wah Shun’s top disciples), and Chan Yiu Min (his son). Both of these individuals ran successful schools that became hubs of the Wing Chun community. Their careers, as well as those of often overlooked individuals such as Jiu Chao, Lai Yip Chi and Cheung Bo, help to illustrate the ways in which the region’s martial arts marketplace evolved in the Republic era, and became enmeshed in the complex social conflicts that would ultimately bring the period to a close.[xvii]

The Hong Kong Period

The lasting legacy of the Republic era was to move Wing Chun beyond being a relatively insular lineage-based project. It was during this period that the art established a public presence, the first modern commercial schools were opened, and the system’s conceptual identity, outlined in its creation myth, was established. Such a story was likely necessary for marketing as this was when the art expended from a handful of practitioners to hundreds of students who found themselves in competition with larger communities such as the Hung Mun Association or the recently imported Jingwu (Pure Martial) Association. Despite this expansion the art continued to be associated with the area’s upper middle class and skilled workers. There is even evidence that both Wing Chun and Hung Gar instruction were co-opted by the area’s yellow trade unions. This close association with regional elites and reactionary groups ensured that Wing Chun practice would not prosper in the years after 1949. While some lineages (such as Pan Nam’s) continued to survive on the mainland, their growth was limited until well after the conclusion of the Cultural Revolution.[xviii]

The situation in Hong Kong was generally more hospitable to martial artists in the 1950s and 1960s. Ip Man fled Guangdong ahead of the Communist advance late in 1949 and with the help of an old friend, Lee Man, found lodging in the communal dormitory of the Hong Kong Restaurant Worker’s Union. In 1950 the now aging Ip Man decided to begin teaching on a professional basis.[xix] Sadly, the sorts of people employed by as restaurant workers tended to be highly transient and this was not good for class retention during the early years of his efforts.

Hong Kong was a very different environment from Foshan. While the KMT had attempted to co-opt martial arts practice, the city’s colonial administrators distrusted them both for their association with Chinese nationalism and Triad networks.[xx] Hong Kong’s urban environment offered a wider variety of distractions and disruptions for Ip Man’s younger students, many of whom were struggling to come to terms with a system of dual colonization where they were cut off from the Chinese mainland, yet also the subject of British Imperialism. Western economic sanctions designed to punish the PRC after 1949 also had a devastating impact on Hong Kong’s traditionally trade-based economy causing massive dislocation as the city struggled to resettle vast numbers of refugees.[xxi]

Succeeding in such a marketplace would not be easy. Ip Man began to streamline and modernize his presentation of material to meet the expectations of his new students. He created public classes with a progressive curriculum where no information was to be held back or kept secret for only select disciples. Within this setting he limited the amount of time spent on initial stance and forms training and instead placed renewed emphasis on a sensitivity drill called chi sao or “sticky hands.”[xxii] The ludic qualities of this training exercise certainly helped with student retention. In its more energetic aspects it also helped to prepare Ip Man’s early students for the roof-top challenge fights that dominated Hong Kong’s martial arts youth sub-culture at the time. The success of many of Ip Man’s early students in these engagements (including individuals like Leung Sheung and later Wong Shun Leung) attracted more students to Ip Man’s growing classes.[xxiii]

These were not the only changes. Ip Man’s two sons, Ip Chun and Ip Ching, both managed to flee across the briefly reopened border and rejoin this father in 1962. They immediately noted that while the basic concepts of his Wing Chun remained the same, the art that he was teaching in Hong Kong appeared differently from how it had been presented during the Republic era. Not only had the curriculum been standardized and rearranged, but it was introduced to students in fundamentally different ways. Traditional ideas and concepts such as the ‘five phases’ (sometimes translated as ‘elements’) or the ‘eight directions’ had been eliminated from discussions. Instead Ip Man drew on his Western education and explained things in simple mechanical terms.[xxiv]

Describing his thoughts on the art to a young Western visitor in 1960, Ip Man told Rolf Clausnitzer that he ‘Regarded Wing Chun as a modern form of Kung Fu, i.e., as a style of boxing highly relevant and adaptable to modern fighting conditions’.[xxv] This same program of pragmatic modernization and reform, originally intended to make the art more attractive (and effective) within the Hong Kong marketplace, and would ultimately lay the groundwork for its global expansion. While a previous generation of teachers in Foshan had struggled to establish Wing Chun as a publicly taught system in a crowded marketplace, Ip Man’s career inadvertently set the stage for the practice’s global expansion.

Wing Chun as a Global Art

It is interesting to note that as early as 1969 Clausnitzer had already predicted that such a thing might be possible, even in an era when most Western martial artists were more interested in the Japanese fighting arts than their Chinese cousins. The key to this future expansion lay, in his estimation, in the education and relatively liberal attitudes of most of the system’s younger students, at least when it came to teaching the art to foreigners.[xxvi]

Still, it is easy to overstate the supposed secrecy of Chinese instructors in the West during the 20th century. More significant was the fact that Ip Man’s students began with some advantages when it came to spreading their art. Hong Kong itself has always served as a meeting point between Chinese and Western culture. During the 1960s and 1970s it was involved in the global exchange of goods, capital, people and ideas in ways that other areas of China were not. As a British territory many of Ip Man’s students had worked diligently to learn English during their school years. They also enjoyed opportunities to seek schooling or employment in the West which other Chinese youth lacked at the time.

Ip Ching has noted that during this period many of his father’s students felt compelled to go overseas to advance their careers. The issue was the state of higher education in Hong Kong. Simply put, educational reforms had been successful enough that the city’s schools were producing more graduates than their small university system could absorb. Traveling overseas to finish one’s education or find professional employment thus became a necessity for many of Ip Man’s better off young students.[xxvii] In comparison to other traditional Chinese martial arts, Wing Chun had been exporting potential instructors for years.

The final ingredient which propelled Wing Chun from a once regional fighting system to one of the most popular arts in the global marketplace was the fortuitous return of Bruce Lee, Ip Man’s most famous student, to the United States in 1959. Lee, originally born in California, was already well known in Hong Kong as a child actor, having starred in a number of popular films. However, he was a hyperactive child who had problems in school. After becoming a Wing Chun student he followed individuals like Wong Shun Leung and William Cheung into the violent world of roof-top fighting. Eventually his parents sent him to America to make a fresh start.[xxviii]

Bruce Lee promoted the Chinese martial arts along the West Coast and began to make appearances in Black Belt, the most important English language martial arts magazine of the period. Images of Ip Man even appeared in some of these articles giving both his teacher and original style an unprecedent amount of exposure in a period when most American martial artists knew little about the Chinese martial arts.[xxix] Eventually Lee would go on to create his own system (Jeet Kune Do), which subsequently had a somewhat complex relationship with the traditional Wing Chun community.

Nevertheless, it was Lee’s return to acting that did more to advance the global popularity of Wing Chun than any other single factor. Martial Arts fans were energized by his performance as Kato in the Green Hornet. But it was the release of the blockbuster Enter the Dragon in 1973, shortly after Lee’s own untimely death, that would make him a global phenomenon.

This was the first kung fu style action film shot in English and supported by a Hollywood studio. It created a level of cultural interest in, and desire for, the Chinese martial arts that had never before been seen in North America or Europe. Audiences were mesmerized by Lee’s martial performance, and the alternate vision of masculinity that was read onto his highly developed physical form. Likewise, minority audiences were drawn to the anti-imperialist messages in this and his prior films. [xxx] Suddenly people around the world wanted to understand how Lee had trained and developed his unique capabilities.

Overnight martial arts classes were inundated with students across the West world. Ip Man’s students who had previously immigrated to pursue school or career goals were ideally positioned to rapidly expand Wing Chun’s presence in North America, Australia and Europe. Further, the modernized system of hand combat that Ip Man had developed for Hong Kong was relatively easily adapted to the needs and cultural background of these students.

Wing Chun remains one of the most commonly encountered traditional Chinese arts in the world today. Bruce Lee’s continual cultural relevance has helped to sustain popular interest in the art, as have endorsements from celebrity students such as Robert Downey Jr. The release of Wilson Ip’s 2008 fictionalized biography of Ip Man also led to renewed interest in the art in both the West but also within the PRC. While Ip Man often spoke out against fantastic Kung Fu legends, his posthumous transformation into a legendary fighter and nationalist hero has helped to spread the popularity of his art far beyond its native Guangdong.

oOo

[i] Benjamin N. Judkins and Jon Nielson, The Creation of Wing Chun: A Social History of the Southern Chinese Martial Arts, (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1998).

[ii] Robert Chu, Rene’ Ritchie and Y. Wu, Complete Wing Chun: The Definitive Guide to Wing Chun’s History and Traditions (North Clarendon VT: Tuttle Publishing, 1998). For a detailed comparison of the unarmed and weapons sets taught in the most commonly encountered Wing Chun lineages see the reference work provided by Chu, Ritchie and Wu.

[iii] J. Elliott Bingham, Narratives of the Expedition to China, from the Commencement of the Present Period, Vol. 1. (London: Henry Colburn Publishers, 1842), 177-178. Bingham provides a historically important first-hand account of militia troops in Southern China training with the hudiedao during the period of the Opium Wars. Also see Judkins and Nielson, The Creation of Wing Chun, 70, 94.

[iv] Judkins and Nielson, The Creation of Wing Chun, 92-99; 117-118.

[v] Yimin He. “Prosperity and Decline: A Comparison of the Fate of Jingdezhen, Zhuxianzhen, Foshan and Hankou in Modern Times.” Frontiers of History in China 5, no. 1 (2010): 52–85. Translated by Weiwei Zhou from Xueshu Yuekan (Academic Monthly) 12 (2008): 122–133.

[vi] Researchers should note for instance that Foshan is also remembered for the important contributions which it made to the development of styles such as Choy Li Fut, Hung Gar, and its thriving Jingwu Hall prior to the Japanese invasion in 1938. All of these styles were better known than Wing Chun during the Republic period.

[vii] Frederick Wakeman, Jr., Strangers at the Gate: Social Disorder in South China, 1839–1861 (Los Angeles: University of California 39 Press, 1997), chapters 13–15.

[viii] Douglas Wile, Lost T’ai-Chi Classics from the late Ch’ing Dynasty (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 5, 20–26.

[ix] Ip Chun and Michael Tse, Wing Chun Kung Fu: Traditional Chinese Kung Fu for Self-Defense and Health (New York, St. Martin’s Griffin, 1998), 20–21.

[x] Douglas Wile, in his 1996 introduction to the Lost T’ai-Chi Classics, systematically laid out the reasons why many of the most ancient seeming Chinese martial arts are fundamentally products of the modern era. Everything that he argued in that work applies equally as well to the hand combat systems of Southern China, including Wing Chun.

[xi] Ip Man, ‘The Origins of Ving Tsun: Written by the Late Grand Master Ip Man’, <http://www.vingtsun.org.hk/>; Ip Ching, ‘History of Wing Chun’ (Ip Ching Ving Tsun Association, 1998), DVD; Ip Chun, Wing Chun Kung Fu (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998), 17–20.

[xii] Judkins and Nielson have provided a review of the known biographical details of all three of these individuals which goes beyond the confines of the current discussion.

[xiii] Meir Shahar, The Shaolin Monastery (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2008), especially chapter 6.

[xiv] Stanley Henning, ‘Thoughts on the Origins and Transmission to Okinawa of Yongchun Boxing’, Classical Fighting Arts 2, no. 15 (2009): 42–47.

[xv] John Christopher Hamm, Paper Swordsman: Jin Yong and the Modern Chinese Martial Arts Novel (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2006), 34-36.

[xvi] Andrew D. Morris, Marrow of the Nation: A History of Sport and Physical Culture in Republican China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), chapter 7.

[xvii] Judkins and Nielson, The Creation of Wing Chun, 169-211.

[xviii] Ibid.

[xix] Ip Ching and Ron Heimberger, Ip Man: Portrait of a Kung Fu Master (Springville, UT: King Dragon Press, 2003), 25, 33.

[xx] Daniel M. Amos, “Spirit Boxing in Hong Kong: Two Observers, Native and Foreign,” Journal of Asian Martial Arts 8, no. 4. (1999), 10.

[xxi] Judkins and Nielson, The Creation of Wing Chun, 214-215.

[xxii] Chun and Tse, Wing Chun Kung Fu, 40-42; Yip Chun and Danny Connor, Wing Chun Martial Arts: Principles & Techniques (San Francisco: Weiser Books, 1992), 26.

[xxiii] Judkins and Nielson, The Creation of Wing Chun, 228.

[xxiv] Michael Tse, “Master Ip Ching,” Qi Magazine 24 (1996): 16–20; Chun and Tse, Wing Chun Kung Fu, 40-42.

[xxv] R. Clausnitzer and Greco Wong, Wing Chun Kung Fu: Chinese Self- Defence Methods (London: Paul H. Crompton LTD, 1969), 10.

[xxvi] Clausnitzer and Wong, Wing Chun Kung Fu, 12.

[xxvii] Ip Ching, ‘History of Wing Chun’ (Ip Ching Ving Tsun Association, 1998), DVD.

[xxviii] Matthew Polly, Bruce Lee: A Life. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018).

[xxix] Anthony DeLeonardis, ‘Martial Arts in Red China Today’, Black Belt, February (1968), 22. The inclusion of a photograph of Ip Man and text block highlighting Wing Chun in one of Black Belt’s earlier features on the Chinese martial arts is typical of Lee’s success in promoting his teacher’s reputation abroad.

[xxx] Paul Bowman, Beyond Bruce Lee: Chasing the Dragon through Film, Philosophy and Popular Culture (New York: Wallflower, 2013).

oOo

If you enjoyed this essay you might also want to read: “Ng Chung So – Looking Beyond the “Three Heroes of Wing Chun.”

oOo

September 30, 2019 at 1:27 am

Howdy. Reading through, I wonder if you meant “Communist advance” rather than “community advance.”

Advance that community with impunity!

Joe barfield

Sent from my phone