What follows is the first part of a short series on New World stick and knife fighting traditions by my friend Dr. Michael J. Ryan (SUNY Oneonta). I first became aware of this vast and fascinating body of material when I had an opportunity to attend a workshop on Haitian Machete fencing sponsored by the German Blade Museum and arranged by Dr. Sixt Wetzler (another good friend whose name will already be familiar to many readers of this blog). The material that I saw was fascinating and it convinced me of the need for a deeper and more detailed discussion of the fighting systems seen throughout the Caribbean and South America.

It is thus with great pleasure that I introduce a two part series on this very topic. In the first half of this essay Ryan described the unique fighting arts that developed in Barbados and Trinidad and Tobago. The second installment will explore the geographically and stylistically diverse fighting methods of Venezuela and Columbia. Ryan’s discussion focuses on the development of unique stick and machete fighting methods in each of these areas, and the various ways in which patterns of trade, colonialism and slavery shaped the development of these New World fighting methods. Now, if only we could find someone to contribute an essay on Haitian Machete fencing….

Introduction

A number of tell-tale signs point to a wealth of living combative traditions in Latin America and the Caribbean, if one goes off the beaten path and keeps one’s eyes open. A farmer riding his bicycle along a rural path with a three-foot stick, strapped underneath his frame. A night watchman in Barbados strolling along the grounds of a factory late one night giving a twirl a three and a half foot stick. Alternatively, while enjoying Carnival in Trinidad and Tobago one may come across two men in brightly adorned devil costumes thrashing each other mercilessly with a long rope or shorter steel cable whips.

One question arising from this wealth of traditions is the differences in the way these men choose to fight. There are common elements among these arts, such as the one-on-one ritualistic nature of these combats and that many of these arts deeply connect with local African-descended communities (with midwestern Venezuela being a notable exception). Also the use of the stick or the blade being highly valued over firearms (again, with the use of whips in Tobago being a notable exception). Examining the variety of the sticks or blades used in these areas in different combative modalities such as bar brawls, sporting events, or traditional celebrations leads to a range of interesting questions.

At this time, however, the focus of our discussion turns to the connections surrounding the development of these arts as emerging out of a set of historical, political, economic structures, and cultural norms. In order to further explore the nature of these linkages, instead of looking solely at the Caribbean or only Latin America, two countries are chosen from each region, recognizing that these areas have a long history with each other where the movements of peoples, ideas and technologies crisscrossed the area for centuries. Due to the unique conditions of conquest, colonization, and incorporation into the North Atlantic trade network, this area provides a unique site to examine various ways local combative traditions have shaped and are shaped by larger socio-political and cultural forces that swept through the region.

One proviso to keep in mind when thinking about the origins and development of combative arts was that no ethnic group has ever had a monopoly on armed fighting traditions. In Western Europe, people regularly fought with sticks and blades of various sizes and engaged in rock-throwing melees or duels at both at both the individual and communal levels until the mid-19th century. In the case of Africa, the number of scattered accounts published over the years suggests a widespread existence of armed combative traditions throughout the continent. What this means is there is a real possibility that any combative technique may have quite a convoluted genealogy and that one must draw on other sources to trace an art to specific area and point of time. Furthermore, many of these arts were developed by men whose only goal was to achieve some form of victory and were often quick to take moves wherever they encountered them as long as they were seen as effective. Since combat is a very pragmatic endeavor, this adds another layer of difficulty in trying to trace back a community repertoire of combat. With this mind, we begin in the Caribbean.

Gilpin on the Beach in Barbados with Benji and Keegan. Source: From the Collection of Michael J. Ryan.

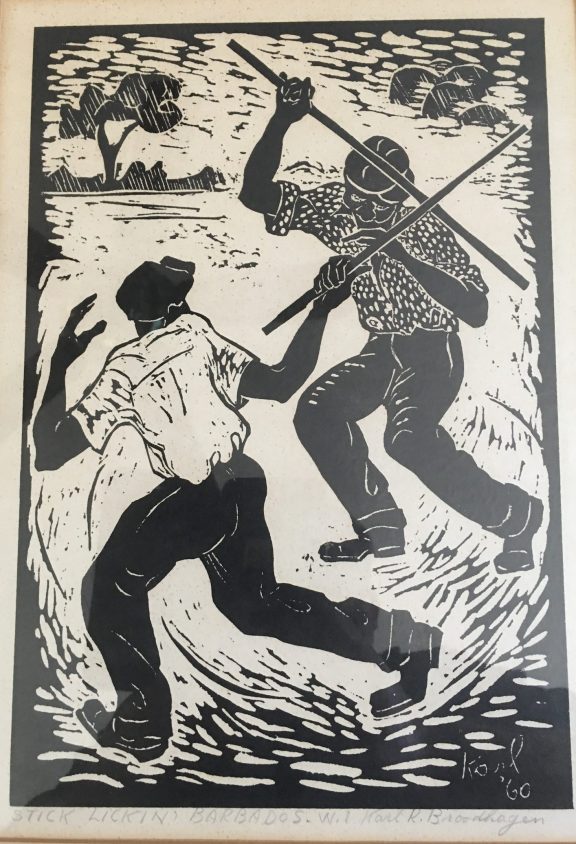

Barbados

The easternmost island of the Caribbean, Barbados shares elements with other countries of interest. This study provides a unique perspective on how the art of stickfighting (or Sticklicking as it is known on the island) evolved over the last 50 years. From a diverse collection of armed and unarmed self-defense and ritual fighting techniques to a popular recreational sport before receding from the public consciousness in the face of cricket and other modern sports. At present it is mainly recognized as part of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) of Barbados.

In simple terms, Sticklicking utilizes an approximately 39 x 1 1/4” hardwood stick against similarly armed individuals. Up until the 1950’s, especially in the rural areas, most men armed themselves with a stick upon leaving their houses. Historically, Sticklicking is best seen as a collection of African stick and single-edged blade fighting traditions that were later influenced by the English saber and single stick traditions. The earliest accounts of stick fighting in Barbados only go back to the 1940’s, which probably betrays the lack of interest local chroniclers had in Afro-Barbadian popular culture rather than a centuries long absence of combative traditions in the country.

One element Barbados shares with every other country under consideration here was the insatiable demand of Western Europeans for sugar. The demand for sugar is what drove a great deal of the transatlantic slave trade and the importation of Africans into the New World. Barbados was first settled by English in 1627. By the 1630’s, the spread of sugar cane plantations on the island had led to the need for a large pool of cheap reliable labor. Captured Africans were brought to the island to deal with this labor issue in such great numbers that after a few decades, the enslaved African populations were double the English population of free and indentured servants.

Another consequence of the ascendancy of an export-oriented plantation-economy was a displacement of small farmers in favor of a planter class who dominated the social, political life of Barbados up through the abolition of slavery in 1834. The Planter class then continued to dominate the countries affairs up through the 1930’s. At this time violent civil unrest spread throughout the British held colonies of Latin America and the Caribbean revolving around the diminishing global demand for sugar exacerbated the already harsh and exploitative conditions of workers who lacked political representation. Only with the advent of independence in 1966 did the plutocracy of the planter elites come to an end.

Phillip and David in sticklicking match in front of a local rum shop. Source: Collection of Michael J. Ryan.

In conjunction with a stranglehold on the political and economic system by a small number of elites, the Church of England played a prominent role in the history of Barbados controlling the educational system and by extension the means for social advancement. For anybody seeking to escape the toil of poorly paid agricultural labor, those in power ensured aspirants embraced English values and cultural practices espoused by the church and supported by the government.

As in many other areas, the beginnings of combative arts that we see today in the New World are challenging to pinpoint. Nevertheless, by the early to mid-19th century chroniclers began to document the existence of unique combative systems throughout the region.

Research by Motteley (2014), and Forde (2018), provides an overview of Sticklicking in Barbados from the 1940’s to today and informs much of the following information. During this time, Sticklicking was present both as an art of self-defense/security tool and as a leisure activity. Interviews with men who were active Sticklickers in the 1940’s present a picture where Sticklicking is highly popular throughout the island and treated as a valued skill. The once wide popularity of sticklicking can be seen in in the number of different styles remembered as being practiced at the time such as Donelly, Maps, Square, Diamond Sword, San Francis, Queensbury, and Johnson. Of these, only the last two remain at present.

In addition to fighting with a 39” or longer stick, some stick lickers also learned how to fight with empty hands alone and in conjunction with stick techniques that included punches, slaps, kicks, trips, hip and shoulder throws. These variations suggest a wide range of combative moves to deal with a variety of modalities, or the rough and tumble nature of combat where one does anything needed to win. Due to the lack of firearms, and possibly a valorization of close quarter combat as the manly ideal of ‘fair-fights’ at the time, men predominately fought with occupational tools such as knives, machetes, and walking sticks. Thus, security personnel such as police officers, night watchmen, and labor foremen, had to possess a level of skill with the stick to control unruly crowds of disgruntled or overly excited peoples.

The value of possessing sticklicking skills can be seen on occasions when local policemen would swing by the houses and pick-up locally renowned sticklickers to help arrest particularly noticeable troublemakers. The reputation that these stickmen possessed was carried along as part of a long ongoing pattern of Barbadian emigration around the Caribbean and Latin America to escape the overpopulation and depressed living conditions back home. Many times, their skills with their sticks were used by colonial governments or plantation owners to quell political violence or labor unrest. In fact, the local form of British Guyanese stickfighting of Setoo supposedly disappeared in favor of the proved efficacy of Barbadian sticklicking (Forde 2018). And so came the old adage “Stickman doh ‘fraid no damom.” With a long, oiled hardwood stick in his hand, a Bajan (Barbadian) man would strike fear in the devil himself with his ferocious attacks.

As a recreational activity, Sticklicking was intimately associated with African practices as Africans made up the majority of the population for centuries. From early accounts around the WWII, sticklicking involved men holding the stick near the ends in both hands and dividing the stick into thirds, as is done today in Trinidad and other islands. A shift from a two-handed to a one-handed grip in turn suggests a shift from African understanding towards a European understanding regarding the best way to wield a stick.

Sticklicking as a leisure activity, revolves around social events ranging from dancehalls, casinos, and house parties. Matches were held in a boxing ring, a marked off area or just within a circle of spectators. Three-minute rounds with one-minute rest periods were adhered to. Judges were picked, to enforce a rule system based on points given for successful hits or knockouts, and prize money was put up for the winners. Neighborhood champions would also travel to other parishes to challenge other resident champions. Friends and family and fans would rent trucks or walk to these matches to support their local heroes.

On a more informal level, weekends especially Sundays were times for informal house parties where Tuk bands played, people could buy drinks and food from the woman of the house and men could fight all night long in refereed bouts. Finally, more informal spontaneous fights broke out at parties and rum-shops. Altogether, the evidence suggests that there was a widespread appreciation of sticklicking matches outside the purview of British authorities. In other words, in the face of oppression and injustice, Afro-Barbadian men created and maintained their own social space where older masculine values of toughness, cunning, and physical agility could be tested, cultivated and appreciated by family, friends, and neighbors, creating a sense of community in opposition to the elite planter class and their views of what was proper entertainment. Still, it is interesting is that there appears to be a lack of heavy-handed enforcement of the ban on carrying these types of weapons that was seen in Trinidad and Venezuela.

Nevertheless, the effects of English hegemony seemed to spread among the popular classes during the latter half of the 20th century when the incorporation of English cultural values of sportsmanship, fair-play and even a repertoire of specific techniques, appeared to have reshaped sticklicking. This influence could be seen the way the stick was held, manipulated, areas targeted as well as victory determined being determined by third-party judges. Rules prohibiting the hitting of a person when his back was turned, when he dropped his stick or when he was lying on the ground further reinforced new ideas of sportsmanship.

Around the time of independence, oral accounts suggest the central role of Tuk bands accompanying Sticklicking bouts (playing before and after individual bouts) began to lessen. The way Kalinda is done in Trinidad, the music is key to mastering the art and it is performed in a way that highlights strong African roots. This time of independence is also when the Barbadian search for a national identity came to fruition, and more universal English sports such as Cricket (introduced earlier to promote English values) began to gain in popularity almost wiping out the existence of local art Sticklicking on the island of Barbados. Today there are only three active teachers left on the island who at times give demonstrations at schools and state holidays to promote the island’s heritage.

Kalinda and Whip Jab in Trinidad and Tobago

Flying 200 miles South by Southwest we come to another former English colony whose stickfighting traditions have undergone a journey quite distinct from that seen in Barbados. On the islands of Trinidad and Tobago the stickfighting art of Kalinda is still heavily associated with the pre-Lenten celebration of Carnival. While the whipping arts of the Jab-Jabs are a lesser-known aspect of Carnival and Gilpin, the art of the double-machete was just revealed to outsiders in 2018.

The development of Kalinda, The Whip-Jab and Gilpin, much like Sticklicking in Barbados is connected with the expansion of sugar cane production as one the principal export crops of the New World. First settled by Spanish colonists, Trinidad remained sparsely settled until invitations by local Spanish authorities led French planters with their slaves, free blacks and mixed-blood freemen to relocate from neighboring Caribbean countries in the late 1700’s. England took possession of the island in 1797. By then African slaves were double the population of European inhabitants. Trinidad also shares with Colombia, Venezuela and other countries a tradition of marronage or independent African/ Indian communities; however, the maroon communities were small and relatively quiet in comparison to other colonies in the New World.

Slaves continued to be brought to Trinidad from other Caribbean islands until 1834 when Britain outlawed the practice. This further muddies our attempts sort out the origins of these people’s practices. After the abolition of slavery, the continual need for a reliable, docile and a cheap labor force led planters to bring in indentured servants from India beginning in 1845. By the time WWI was under way, and further emigration ended, an estimated 145,000 people had immigrated to the islands from North-Central India.

Sugar cane dominated the economy in Trinidad until 1884, when the cultivation of cacao began to replace it. The Cacao boom lasted until the 1930’s when a global economic downturn, urban rioting, and local crop related diseases destroyed the market. By the early 20th century the production of oil had overtaken other export crops. Politically, a colony of Britain since 1797, Trinidad and Tobago were ruled by governors selected by the crown who were given almost unlimited powers until 1925, when limited suffrage allowed the election of a proportion of a legislative council. Universal suffrage arrived in 1946, and full independence was achieved in 1976. This progress should not blind the reader to the fact that the state continues to repress alternative ways of belonging and exercising one’s citizenship in a free manner as seen in significant government crackdowns on dissidents as recently as 1980 and 1990.

Benji and Keegan demonstrating Kalinda. From the Collection of Michael J. Ryan.

Kalinda as a stick fighting art and the Whip-Jab is intimately associated with Carnival. However, we cannot forget the existence of Afro-Trinidadian and Indo-Trinidadian combative systems that existed before their incorporation to Carnival nor their use in other modalities besides combative ritual duels. Midwestern Venezuela also provides another example of this where Garrote was seen as predating its connection with the Tamunangue celebration.

At present, Kalinda is a stickfighting or “dueling” art done with a hardwood rod approximately 48 X 1¼”. Kalinda is a refereed sport with one or more judges. In a Kalinda match, a group of drummers stationed alongside the gayelle or ring begin a rhythm, and the chantwelle begins singing a chorus whose response is often picked up by members of a fighter’s entourage and spectators. Two men enter the gayelle where they dance around the open space, and each other evoking their African ancestors. Then each contestant performs a solo series of dance steps to feel the spirits, to loosen up the body and let the spectators know the ancestors and invincible protect them. Striking below the waist is the only principal prohibition. The main target is the head where the boismen seek to cut the other man’s scalp so that he bleeds. However, disabling a man with body shots or leaving the decision to the judges are also alternative ways of winning. If a man’s head is bleeding or is ‘bus open’ he is led to the blood hole in the center of the ring to offer his blood to the ancestors (Greenberg 2009). Then the next match begins.

The earliest accounts of stickfighting in Trinidad suggest there was already a perceived public-safety crisis which inspired the passage of a law prohibiting of Black men carrying sticks over three-feet in length. By the 1860’s, there are accounts of regularly held stickfighting contests among the ethnically marked popular classes drawing young men from the colonial elites known as ‘jacket men’ who would take part in these contests. Crossing racial and class boundaries was a threat to the social order and a cause for public concern. Reading these fragmented accounts suggests that while European forms of blade and stick fencing were a commonly accepted pursuit among elite young men at the time (Hill 1972:25), interacting with African boismen who were clearly not their equals exposed the upcoming generation to the debased superstitions and vices of the most disreputable class of society (Cowley 1999:124).

Kalinda’s repression in the late 19th and early 20th century has parallels with the repression of other popular ethnic or class expressions, such as Capoeira in Brazil and Garrote in Venezuela. In these countries, governments imposed laws and instituted infrastructural projects designed to erase the mark of stigmatized communities in urban areas in the drive to modernize and bring their countries in line with Western Europe patterns.

During these repressive decades, in the rural areas away from strict colonial oversight, secret societies, fraternal orders, churches and village community groups would keep alive older traditions linking them to their African ancestors. Sites would be created and protected where young people could gather to meet socially and engage in rituals of courtship and agonistic competition. These socially sanctioned fights would give young men an opportunity to engage in risky situations whose outcomes could burnish one’s reputations of toughness, cunning, resilience. The resulting social capital could be converted into desirable marriages or an increase in wealth through security jobs or participation informal/criminal enterprises. While outlawed early in the 20th century, Kalinda still played a role in Carnival with newspapers covering the crowning of new Kalinda Kings up until the 1980’s. As part of a drive to create a sense of national identity among the diverse peoples on the islands, the 1940’s’s saw a shift promoting once stigmatized rural African, and South Asian cultures while forgetting others, such as Chinese. By the late 1990’s, due to the state promotion of village traditions, Kalinda was again treated as an integral feature of Carnival.

Ronald and Benji as Jab Jab Men. From the Collection of Michael J. Ryan.

Carnival, Kalinda and Whip-Jab

Carnival was first celebrated in Trinidad in the late 18th century. Originally an elite pre-Lenten costumed celebration, the European descended planter class could dress up like African slaves in private homes and have a good time before the austerity of Lent. After slavery was abolished in 1838, free African began to celebrate their own Carnival processions in public places known as Canboulay, where once oppressed communities could celebrate their freedom and collective power. Neighborhoods would construct their floats and display their personally costumed revelers in street parades. Upon meeting other neighborhood Canboulay groups, boasts and taunts directed towards each other would often lead to challenges and ritual duels with heavy hardwood sticks leading to a never-enforced ban on Canboulay in 1868. In addition to intimidating and repelling elites through their unique celebrations, Boismen or stickmen would take the opportunity to harass, intimidate and assault local Indian merchants and laborers. In turn this led to merchants hiring men skilled in the Indian stick arts such as Lathi, Gatka or Shastra Vidya to protect their community. They were also deputized by the local police chief of Port of Prince one night in 1880 to help the police in putting an end to one of the biggest acts of civil unrest the island. As a result of these clashes, the governor rescinded the earlier ban on Canboulay.

During this time Canboulay was treated as a prequel to the Carnival which had a profound effect on its form. The domesticating of the excesses of the transgressive revelry through combining both events resulted in a concomitant decline in the popularity of stickfighting matches and greater participation by an emerging middle class of the island. Then in 1904, the Trinidadian state was able to enforce a ban on the carrying of sticks longer than three feet in length or hitting each other with these sticks, leading to even further widespread decline of the art. A set of further restrictions on Kalinda players and African drummers in 1944 coincided with the advent of WWII. The increased presence of allied ships and personnel in the area contributed to the development of steel-pan music and local street fighters putting down their big two-handed sticks in favor of switchblades and other small concealable weapons to continue their contests and informal economic activities (Cowley 1996). The role of Gilpin as a double machete art claims the same social roots. I learned that the art was always held in secret until it was extensively documented by the 2018 ILF hoplology expedition members because some local teachers were afraid the art was going to disappear.

The profound influence of North Indians in Trinidad and Tobago is especially visible in the carnival mas or costumes of the Jab Jab men. The Jab Jab characters are a later addition to the series of accepted costumed characters paraded during carnival. They are dressed in a brightly colorful satin costume hung with bells and decorated with mirrors and rhinestones. On the head, a hood with stuffed clothed horns protrude and other sacred symbols completes the mas.

Fiber whips used in the Jab-Jab system. Source: From the Collection of Michael J. Ryan.

The Jab Jab men lead the local carnival floats. Upon meeting another float protected by other Jab Jab men, they duel with long cactus fibered whips that can tear the cloth of a Jab Jab man while leaving his skin intact, shred his skin to ribbons while leaving the costume whole, or cutting the seams of the other Jab Jab leaving him naked in the street. The predominant target though was the eyes resulting in several blind or half blind Jab Jab men and a decrease in the number of young apprentices. The shorter whip made of steel cables, in turn, can break bones and rupture internal organs.

What is interesting about the Jab Jab devil-men are their strong links with the North Indian herding cultures and the worship of the goddess Kali along with African Orixas. These men have highly specialized knowledge of local medicinal plants and hold themselves to a high degree of comportment all year long. Then one month before Carnival they dive into an even more rigorous regime of fasting, mediations, visualizations, herbal baths, and prayer to prepare themselves for the upcoming whipping duels.

What is unique in these ritual duels of the Kalinda and the Jab Jab men is the deep connection to ancestral origins seen in the music, dress, language, and beliefs of participants. This rich visual, aural, and emotional evoking imagery is quite different from the stripped-down austere stick play of the Barbadian Sticklickers today. While these islands have a shared historical trajectory as English colonies, the enduring role of a French Catholic colonial elite appears to be a determining factor in the perpetuation of these arts. As opposed to a more austere and less tolerant Anglican Church, Catholicism has a history of tolerance towards the syncretic merging of subaltern or colonized communities’ beliefs and practices. In the 20th century, the rise of the nation-state had led several countries to embrace local traditions as iconic expressions of a common root shared by all citizens. In Trinidad, this included Carnival, and which then expanded to include Kalinda. In Venezuela, it led to the renaming of the local festival of St. Anthony of Padua and its raising to the status of a national dance that included the stick duel of garrote as we will see in the next section.

oOo

Michael J. Ryan is an Adjunct Professor at SUNY Oneonta. His research interest include embodiment, modernity, violence, and Hoplology. The author has pursued the formal study of martial art traditions since 1977. Recently, he has teamed up with other scholars to revive the discipline of Hoplology under the banner of the Immersion Labs Foundation (ILF). In addition intensive workshops devoted to knife and stick fighting, the ILF has conducted Hoplological expeditions to Barbados and Portugal.

oOo

If you enjoyed this discussion you might also want to read: The New Hoplology: Stick, Machete and Whip Fighting in the Caribbean

oOo

June 28, 2019 at 12:34 am

I’m sure you already know about https://www.haitianfencing.org/. Whether you do or not, hopefully you’ll join me in encouraging the site’s author to finish and publish his book on the subject. It looks neat, as does this stuff. As a one-time and extremely mediocre practitioner of capoeira, the format of the musicians and two people playing in the circle seems very familiar.