Martial Arts in the British National Press

Paul Bowman

Cardiff University

JOMEC Research Seminar, Cardiff University, 13th December 2017

Introduction

This research project looked at stories, items and features about martial arts in the UK national press.[1] The basic area of enquiry is into the kinds of stories that have been and are being told about martial arts and martial artists in mainstream British popular culture.[2]

This study of the press is only one part of a larger research project, which is looking at the representations of martial arts in a range of different realms of British popular culture, such as films, adverts, magazines, music videos and books.[3]

The project is specifically interested in non-specialist publications, non-specialist texts, and non-specialist contexts. This is because I am interested in finding out what kinds of stories about martial arts circulate in mainstream contexts; what kinds of representations dominate, what kinds of images, associations, connotations, values and understandings congregate around the terms, images and practices, and are available to people who aren’t specifically interested or involved in martial arts.[4]

This is because a premise of this study is that martial arts are neither necessarily nor inevitably to be understood in one particular given way. Rather, the very notion of ‘martial art’ (or as is more common in British English, ‘martial arts’ – plural singular) is a discursive construct.

What this means is that the term itself is neither necessary, nor inevitable, nor straightforward, nor transparent. It is something that has grown and developed – or been cobbled together. It has a history. And I want to explore this construct, in terms of a few key premises and hypotheses, and with a view to testing the validity or verifiability of some things that are sometimes claimed about martial arts.[5]

Theory

My hypotheses come from discourse theory.[6] However, like the discourses that discourse theory theorises and discourses upon, discourse theory itself is a rather difficult thing to demarcate. It doesn’t have one stable identity or one necessary approach (despite the scientistic impulses of some approaches).

This lack of unity in both the subject and the object of discourse arises because the word ‘discourse’ is irreducibly metaphorical,[7] and the objects and fields that are discursively constructed within the discourse of discourse studies (or theorised in discourse theory) can only ever really be indicated, evoked, conjured up, or argued for, rather than specified and measured unproblematically. A discourse is not a referent. It is a construct. The claim that ‘this or that discourse’ exists ‘out there, in the real world’, is at root, only ever an argument.

Perhaps this is not the place to interrogate the ontological status of discourse theory and discourses in the world. But I do want to say a couple more things on the subject, as quickly as possible.

Firstly, because of the premise of the power of open-ended articulation and ever-altering reiteration (in all versions of discourse theory), ‘discourses’ are rarely conceived of as being confined to specific spaces, or to closed networks or discrete media. Rather, in discourse theory, the logics of causality and determination are always to some degree unstable and unclear. So discourses can be said to overflow or leap from context to context, medium to medium, language to language, game to game, network to network (or whichever metaphor you use to conceptualise it).

Inevitably, therefore, they are regarded as being variably transformable and transformative. So it’s never entirely certain whether a thing in a given discourse is in fact one thing (or indeed a thing), or whether any putative or notional discourse is in fact one thing (or indeed a thing). This is because, once a thing is understood to be a construct, it becomes eminently deconstructable. It is a construct because it is not one thing. Hence it is deconstructable.

(As an aside: this is why a lot of schools of discourse analysis disavow any debt to deconstruction, and even denounce it, claiming that you can’t do discourse studies using deconstruction.[8] As certain radical or deconstructive discourse theorists used to say: this is because deconstruction is a condition of possibility for discourse analysis that is by the same token a condition of its impossibility. So you can see the problems right there. But let’s move on from ontological questions.)

Method

Translated into practical terms, most discourse theorists and analysts could possibly agree that modern discursive entities and identities, contemporary terms and values, are all stabilizations that have a history, and will not always have been the way they are now. Consequently, when looking for discourses – especially when looking for discursive development and transformation – one should cast the net wide and be prepared to follow any lead and any possible line or angle – like a detective – rather than sticking to contemporary notions, current terms, and present assumptions about stable entities and identities.

Accordingly, the very terms that structure this project (‘martial art’, ‘martial arts’, ‘martial artists’, and so on), should be understood to be modern constructions. This means that, to get a sense of the movements, changes, developments, modifications and tectonic shifts that have gone into making our modern terms and commonplaces of everyday life, one should search very widely, diversely, creatively, and dynamically.

However, we did the exact opposite of this. Rather than chasing around in the murky prehistory and twists and turns in the development of martial arts discourses, my research assistant (Paul Hilleard) and I instead chose two contemporary British terms – ‘martial arts’ and ‘martial artist’ – and looked for the occurrence of only these two things throughout the archives of five national British newspapers.

The reason for this is that we already knew that these terms are comparatively recent stabilizations. They may seem familiar, natural, and universal to us today – as if they have been around forever. But they have not.

(One recent study looked at adverts for what we now call self-defence and martial arts schools and classes in the USA. It found that, in the USA, such terms as ‘martial art’ or ‘martial arts’ really only become predictably frequent, stable, regular, self-evident and organising rubrics during the 1990s.)[9]

We may wonder what (if anything) preceded our current terms. Martial arts historian Joseph Svinth has pointed out the difficulty of finding reliable search-terms when trying to get a sense of the historical development and changes in martial arts discourse, in different places.

Even if we are looking only at ‘the British context’, Svinth notes,[10] there are actually several of these (there is the UK, and Northern Ireland, then pre-separation, Commonwealth, and so on); and there are different terms and different uses of related terms in different places, such as Australia, Canada and New Zealand.

Svinth himself has widely researched British newspapers, looking into such matters as the reporting of boxing deaths. Hence, he notes that historically the word ‘boxing’ can mean ‘a box for your lunch, a slap to the ears, a brawl at the pub, or a betting occasion outside of town. The Americans are worse’, he adds: synonyms for boxer ‘include bully, shoulder-hitter, pugilist, pug’, and more. ‘And even in Britain, during mid-Victorian times, the papers sometimes made the distinction between bare-knuckle boxers and glove fighters’.

Consequently, Svinth recommended that we search newspapers using terms that would be ‘very politically incorrect’ today. ‘For instance’, he suggested, ‘search “Jap wrestling”, “Chinamen AND boxing”, “Hindoo AND stick fighting”, and so on’. As he notes, ‘Jack Johnson was not described in kind terms in the sporting press of 1910’.

As Svinth points out, old martial arts stories may be organised by terms as diverse as ‘old Samurai art’, ‘antagonistics’ or ‘assaults-at-arms’. In the 1920s, terms like ‘all-in fighting’ and ‘dirty fighting’ emerged, along with ‘commando tactics’. ‘Judo’ was also sometimes used to mean ‘dirty fighting’, rather than Kodokan judo. ‘Then as now’, writes Svinth:

the distinction between theatrical and practical use was often not remarked. Thus, you’ll see Chinese street entertainers and sword dancers, Indian dacoit and fakirs, Turkish strongmen, and so on, all doing what we’d today call ‘martial art’, but were then viewed as curios… [Similarly] circus and music hall [has long been] a place to look for feats of swordsmanship, archery, stick fighting, and so on. The British booth fighters and the Australian tent fighters are straight out of this tradition.

Then there is the time-honoured problem of variant spellings. The way we spell judo, jujitsu, capoeira, tai chi, and myriad other terms is a matter that is still mired in difficulties and differences – and in some cases will always be.

As such, tackling the prehistory of our current discursive conjuncture – in which the term ‘martial arts’ can be assumed to need no explanation to most people – just as terms like ‘teenager’ or ‘air quality’, ‘Brexit’ or ‘climate change’ seem to need no explanation to most people (even if they could benefit from it) – was way beyond the scope of this study.

Neither my research assistant nor I had the time or the means at our disposal to try to excavate the ancestors of the terms ‘martial arts’ and ‘martial artist’. We did not want to play search-term battleships or bingo.

So we used these broadest of contemporary search terms, in order to find out where and when and how our current terms appeared and developed. As such, this research is into the development of the current discursive conjuncture, and is not a genealogy or history of any of the precursors of the terms, concepts or practices. It is about the coming into focus of the present conjuncture, and what that conjuncture looks like and looks at.

Value

The value of this kind of project relates to another key tenet of all discourse theories: namely, the proposition that the way something is understood and valued (or devalued) in ‘wider cultural contexts’ (aka ‘in general’) and in powerful social institutions can be influenced by general tendencies in representational practices.

Put crudely, if we constantly hear (for instance) that many capoeira practitioners are criminals, or that many criminals are capoeira practitioners, then we may disapprove of capoeira – we may even want to make it illegal, or be happy if it is illegal. Conversely, if we constantly hear that capoeira is an ancient, complex, subtle, athletic, balletic, skilful and culturally rich tapestry of African slave and indigenous Brazilian culture, then we may value it, cherish it, fetishize it, even fantasize or elaborate ideas of cultural identity in and through and around it.

Both of these situations have existed, at different times, in Brazil.[11] Other equivalent situations vis-à-vis different martial arts in different countries exist today.[12] Representations and values differ – both across time and across space.[13] What seem key are the stories that are told and the associations that are made. And this is what this research project sought to investigate around martial arts in the British press.

Size and Scope

Five national British newspapers were surveyed: The Daily Mail, The Times, The Daily Mirror, The Guardian and The Independent. We had access to archives spanning different time periods for each. Not everything was from the beginning of each newspaper’s history until the present moment.

- Results from The Daily Mail archives spanned 1970 to 2004, a period of 34 years. The total number of results recorded, omitting repeated items like adverts, came to 101.

- Results from The Times archives spanned 1974 to 2011 – a period of 37 years. Repeated items were omitted, and the total number of results recorded was 268.

- Results from The Daily Mirror archives spanned 1918 to 2017, but the solitary item from 1918 is only a play on words,[14] and from 1918 onwards there is long gap, until the next item occurs in 1974. So, really, The Daily Mirror results span 1974 to 2017 – a period of 43 years. Despite this long period, the total number of items recorded is only 77.

- Results from The Guardian cover 1992 to 2017 – a period of 25 years. The total number of items recorded is 111.

- Similarly, The Independent covers 1992 to 2017 – the same 25 years. The total number of items recorded is 128.

- This means that the total number of items recorded in the study was 685.

Methodologically speaking, if we wanted to do certain kinds of things with the findings, we would have to either (i) open things up considerably, or (ii) close them down systematically. So, if we want to compare and contrast the newspapers in various scientific or scientistic ways, we would either need to gain access to the entire archives of all of the newspapers (which we couldn’t), or delimit our discussion to either an arbitrary or a specific time period.

An obvious arbitrary time period would be between 1992 and 2004 – the only period we have access to all of these newspapers. Conversely, an obvious specific time period would relate to the timeline of a specific event or story – such as, for example, a period of time from before the first murmurings that UFC champion Connor McGregor first announced that he wanted to fight multiple world champion boxer Floyd Mayweather Jr., through to some time after the post-fight analysis.

But the main aim of this first study was to get a clearer sense of what kinds of stories were out there, being reported, being told, about martial arts and martial artists in the British national press.

Daily Mirror

If we take the tabloid paper, The Daily Mirror first, of the 77 items mentioning martial arts/artist, there are at least nine which I called ‘incidental’ – i.e., where the terms appear as comparisons, analogies, or tangential asides (so, something is said to be ‘like a martial art’, or a term is really only the name of a race horse or a crossword clue, and so on, or a key term is added as a piece of information about someone or something – such as a celebrity who ‘is a martial artist’ or ‘practices the martial art of wing chun kung fu’, etc.).

These ‘incidental’ uses of martial arts are in themselves potentially significant, in what they suggest about the understanding of the entities, notions or practices of actual martial arts.

The first item about tai chi, for example, is wonderfully illustrative of the value of ‘incidental’ mentions. It occurs in a 1999 item about new entries in the Encarta World Dictionary. The Daily Mirror notes that Encarta feels tai chi is understood by around half the population as some kind of Chinese martial art. So this is interesting. I’ll come back to it.

There are other frequent tangential or incidental occurrences, such as obituaries, and the fixation of the columnist Tony Parsons on boxing, which he repeatedly characterises as Britain’s indigenous martial art. Parsons also returns several times to the story of footballer Eric Cantona who famously jumped at someone in the crowd with a side-kick.

The question of how representative Tony Parsons’ fixation on boxing is of anything more than his own idiosyncrasies is something that would require further and wider discussion.

But there are some other regularities, produced by multiple authors, that stand out and grab the attention in a different way. One is the status of tai chi.

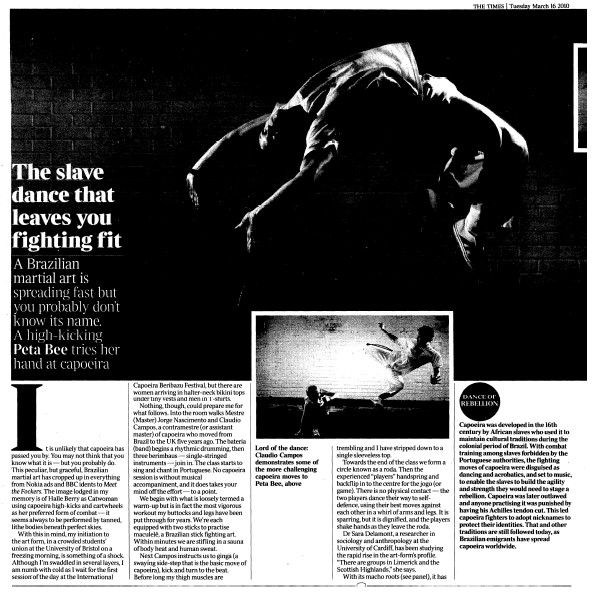

There are eight articles on tai chi. This makes it the most frequently mentioned martial art – more frequent than taekwondo (six stories), judo (four stories), and the surprising occurrence of capoeira (four stories).

I was surprised about the appearance of capoeira in The Daily Mirror because I seemed to have passively accepted claims made by certain ethnographers that very few people in Britain know what capoeira is. Academic ethnographic publications about capoeira continue to appear which operate in line with the assumption that it needs explaining to readers; and yet here it is, in a Daily Mirror story about Charlize Theron learning capoeira moves for a film role in 2005, and then in a story about the British football team attending a capoeira demonstration in 2014 in Brazil, and then in two stories about Joe Joyce celebrating his boxing victory at the 2016 Olympics with a capoeira performance of his own.

In fact, these capoeira stories encapsulate the ways that The Daily Mirror handles most martial arts stories: martial arts are mostly made sense of in terms of celebrity activities, fitness fads and film roles; or as sports (in the case of taekwondo and judo), or occasionally as curios from other cultures that visiting dignitaries abroad have to sit through, or supposedly salient pieces of information about violent criminals, or self-defence narratives. An ideal Daily Mirror story would involve a female celebrity surviving a violent attack at a sporting event thanks to moves she’d learned for her new film role, perhaps with the assistance of a passing postal worker who’d been taught self-defence as a new initiative in the postal service.

But then there is tai chi. There are three stories The Daily Mirror tells about tai chi. The first is that it is an ancient Chinese martial art involving yin and yang. The second is that women should do it – to find ‘balance’, to ‘balance’ their ‘energies’, and so on. And the third is that old people should do it.

For old people, tai chi promises longevity, health, balance and physical energy. For younger women, it offers metaphorical balance. Some men report on the tai chi they have tried in their travel journalism trip to Hong Kong, for instance, but the target audience remains women and old people.

Daily Mail

To stay with this focus on women and old people, we could now turn to The Daily Mail. Of 101 references to martial arts, 13 are ‘positive’ stories about tai chi. Again, these are almost invariably health stories providing information for women or the elderly. Again, there are no negative stories about tai chi. The closest we come to anything remotely like a negative statement is one article that suggests younger people should ‘also’ do more vigorous exercise.

However, tai chi is not the most frequently occurring subject. It is second to aikido, about which there are at least 17 stories. But, the vast majority of these are columns by Nigel Dempster, The Daily Mail’s ‘Tony Parsons’ in his fixation on one recurring subject.

Indeed, Dempster is worse than Parsons, in the sense that he merely repeats the same phrases over and over again. These are phrases which connect aikido with a handful of aristocrats and their acquaintances. Dempster regularly reports in on a certain Earl of Cawdor – a kind of playboy about whom Dempster always tells us two things: first, that he is a descendent of Macbeth; second, that he practices aikido.

Dempster’s aikido-aristocracy focus also draws him into aikido stories about royals and celebrities. But after Earl Cawdor’s obituary in June 1993, other than a couple of stories about people who stop being ‘slobs’ by taking up aikido, it tails off as a topic.

There are frequent stories involving other martial arts, including a surprisingly ‘pc’ micro-article about how insensitive it is that the BBC used white capoeira performers in one of their ‘idents’ when capoeira is originally an afro-Brazilian slave practice.[15]

There are also intermittent ‘how to choose a martial art / physical activity’ features.

But the stories about tai chi (and related practices like qigong) are of a qualitatively different order. Other martial arts are often mentioned in the context of someone famous, or as a side issue, subordinate to a different story or focus. But when tai chi appears, it is front and centre, the main focus.

Tai chi is always viewed positively. There are often articles advocating that people try it. It often appears in the ‘Femail’ or ‘Health’ sections, and is often positioned as something that prevents osteoporosis, improves joint health, mobility, balance, and helps to de-stress. So it is positioned as explicitly healthful, implicitly feminine and aimed either at women or older readers.

Both The Mirror and The Mail are enamoured of tai chi’s meditative dimensions, which they treat as ways to de-stress, combat hypertension, etc. However, they do not explicitly follow an orientalist or mystical mumbo-jumbo angle. Nonetheless, the mind-body connection theme could be regarded as a precursor to the even more recent interest in ‘mindfulness’.[16]

There are slight spikes in martial arts stories around 1974, the mid-1990s, and an upward trend from 2000. It is never stated, but the 1974 spike probably relates to the ‘kung fu craze’ which peaked at that time. The spike of the mid-90s relates to stories about kickboxing as an exercise craze, often for women, coming from the USA, especially in relation to celebrity females. The spike of the early 2000s relates to the newer iteration of kickboxing, known as Tae-bo (also boxercise and kick-boxercise), and also the emergence of a kind of neo-hippy new age ethos that seems evident in certain items.[17]

One can certainly see the formation of a kind of feminised deracinated and only crypto-orientalist new age sensibility, in which tai chi, yoga and mindfulness come to represent sensible antidotes to stress, aging and infirmity. These practices are articulated in very different ways from sports martial arts like taekwondo, on the one hand, and budō arts like kendo, on the other, and even so-called traditional martial arts like karate. The latter are strongly connected with ideas of ethics, honour, control, Zen, Buddhism and specific Asian traditions. Tai chi is deracinated.

Two quick final points about The Mail. First, it is interesting that the very first story we found in The Daily Mail in 1970 is one debunking the myth of the black belt as proof of invincibility. This is the first story: the debunking a myth. This means that there was already a well established body of cultural discourse (mythology) on Asian martial arts at the time, even though the article does feel the need to give definitions and introductions to practices like karate and judo. However, the point is: the first story signals the existence and familiarity of martial arts myths before the first story about them in The Mail.

Second, The Mail (like The Mirror) does not register the rise of mixed martial arts (MMA) in the wake of and around the explosion of interest in the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC), which has grown ever more prominent year by year since 1993.

The Guardian and The Independent

Both The Guardian and The Independent, however, become completely dominated by the UFC. Surveying The Guardian, for instance, there are no clear patterns in martial arts stories. Games reviews, film reviews, health items, and occasional news stories are all present in equal numbers. But by 2015, stories about the UFC are taking off and taking over. There were 29 items on the UFC in the period looked at, from one in 1996 to a rapid proliferation between 2015 and mid-July 2017.

Similarly, The Independent becomes dominated by UFC stories in the same period. There are 31 items on the UFC, starting in 2009, but increasing dramatically from 2015 to 2017. The search terms also picked up 10 articles on boxing. Of course, there will have been many more stories on boxing, but these ones register in the context of martial arts, and most prominently around the McGregor-Mayweather fight in Summer 2017. So 8 of these articles are about MMA fighter Connor McGregor.

There are other minor patterns in these two publications, but all are dwarfed by recent interest in all aspects of the UFC.

The Times

The Times is different again. It is often written by very well informed writers (e.g., Nicholas Soames, 2nd degree judo black belt). Unlike the more tabloid Mirror and Mail, The Times always seems to assume that the reader already has some knowledge (or at least the ability to follow what is being talked about). So The Times will often discuss specific (often quite obscure) martial arts without any of the Mail’s sense of wide-eyed wonder that such things could possibly exist in the world.

Interestingly, as with The Mail and The Mirror, the Times has a consistent interest in exactly the same kinds of health stories about tai chi. As in the other publications, Olympic sports get more attention in the run up to Olympic Games. Traditional martial arts and budō arts get a fair amount of coverage. And, again, there were lots of stories about capoeira: 21 in total, starting in 1988, with 1-2 stories on average per year from 2000 until 2011. This seems largely to arise because of The Times’ interest in reporting dance and theatre productions, in which capoeira often features.

Conclusion

By dint of the format and characteristics of Times journalism, it is neither easy nor appropriate to reduce articles to one theme or one value. We often find long articles, covering many subjects, often involving relatively meandering first-person accounts. This gives rise to at least three things – which I will mention quickly by way of heading towards some kind of provisional conclusion.

First, it seems OK in The Times to positively delight in violence – as long as (if, and only if) that delight is framed as part of some kind of female self-defence experience.

Second, the longer, possibly more meandering or expansive and literary styles of articles in The Times gives rise to a lot more ‘incidental’ references to martial arts – similes, metaphors, comparisons: many things are said to be (‘like’) a martial art.

In my first pass through the articles, I initially found these ‘incidental’ references to be frustrating – like red herrings giving false readings: interference that I wanted to squelch out. But on reflection, as mentioned, I think that these ‘false readings’ are actually a pertinent research topic in their own right. What do we compare martial arts to? What do we compare to martial arts?

Doubtless, like the seemingly transcultural compulsion to tell the same story about tai chi over and over again, many of these things will appear to be relatively fixed. But, as the recent defeat of a self-declared tai chi master by an MMA fighter in China may presage (and as the many negative stories told about tai chi within specialist martial arts circles are my witness), none of these things are necessarily fixed.

It all depends on how they are read. And this is my third and final concluding point. It all depends on how these things are read. I have certainly not read these stories to you here – either in the sense of recounting them or in the sense of interpreting them. I have kind of indicated, kind of enumerated, kind of introduced. But a great deal more reading needs to take place, both of the newspaper archives and of the many other texts and intertexts that feed into and grow out of it, and others, in other realms and registers of British popular culture.

References

Akerstrøm Andersen, N., 2003. Discursive Analytical Strategies: Understanding Foucault, Kosselleck, Laclau, Luhmann,. The Policy Press, London.

Benesch, O., 2016. Reconsidering Zen, Samurai, and the Martial Arts. Asia-Pac. J. 14, 1–23.

Boretz, A.A., 2011. Gods, Ghosts, and Gangsters: Ritual Violence, Martial Arts, and Masculinity on the Margins of Chinese Society. University of Hawaiʻi Press.

Bowman, P., 2018. The Martial Arts Studies Reader, Martial Arts Studies. Rowman & Littlefield International, London.

Bowman, P., 2008. Deconstructing Popular Culture. Palgrave Macmillan.

Bowman, P., 2007a. Post-Marxism Versus Cultural Studies: Theory, Politics and Intervention. Edinburgh University Press.

Bowman, P., 2007b. The Tao of Žižek, in: Bowman, P., Stamp, R. (Eds.), The Truth of Žižek. Continuum, London and New York, pp. 27–44.

Delamont, S. and Neil Stephens, 2008. Up on the Roof: The Embodied Habitus of Diasporic Capoeira. Cult. Sociol. 2, 57–74.

Downey, G., 2002. Domesticating an Urban Menace: Reforming Capoeira as a Brazilian National Sport. Int. J. Hist. Sport 1–32.

Hall, S., 1992. Cultural Studies and its Theoretical Legacies, in: Lawrence Grossberg, C.N. and P.T. (Ed.), Cultural Studies. Routledge, New York and London, pp. 277–294.

Laclau, E., Mouffe, C., 1985. Hegemony and socialist strategy: towards a radical democratic politics. Verso, London.

Mowitt, J., 1992. Text: The Genealogy of an Antidisciplinary Object. Duke, Durham and London.

Stephens, N. and Sara Delamont, 2006. Balancing the Berimbau: Embodied Ethnographic Understanding. Qual. Inq. 12, 316–339.

Wetzler, S., 2015. Martial Arts Studies as Kulturwissenschaft: A Possible Theoretical Framework. Martial Arts Stud. 20–33. doi:10.18573/j.2016.10016

Žižek, S., 2001. On Belief. Routledge, London.

Notes

[1] Cardiff University Research Opportunities Programme (CUROP), ‘Martial Arts in the UK Press’, PI: Paul Bowman; RA: Paul Hilleard. June-July 2017.

[2] The initial aim of the project was to explore the construction of the figure of the martial artist. The original subheading of the project was ‘From Mindfulness to Madness and Beyond’. This aim was modified to enable more basic research.

[3] The research for this overarching project should hopefully be carried out during the academic year of 2018-19.

[4] I have presented research on other kinds of ‘non-specialist’/mainstream representations of martial arts and martial artists elsewhere: first at a Waseda University Research Group meeting, headed by Professor Mike Molasky, Tokyo, in March 2016; and second at a conference on film dialogue, organised by Evelina Kazakevičiūtė, at Cardiff University in June 2017. The former has been published in my book Mythologies of Martial Arts (2017); the latter will appear in JOMEC Journal in 2018.

[5] In saying this, I had in mind two specific things: first, claims made by ethnographer Sara Delamont, that capoeira is not widely understood in the UK (Delamont, 2008; Stephens, 2006); and second, some arguments made about the shifting discursive status of different martial arts, made by Sixt Wetzler in issue 2 of Martial Arts Studies (Wetzler, 2015).

[6] Specifically/originally, the theory of Laclau and Mouffe, as seen in their book Hegemony and Socialist Strategy (Laclau and Mouffe, 1985). However, my reading of this was modified by Mowitt’s critique of ‘discourse’ in Text: The Genealogy of an Antidisciplinary Object (Mowitt, 1992). I deal at length with my understanding of ‘discourse’ in my own books, Post-Marxism versus Cultural Studies (Bowman, 2007a) and Deconstructing Popular Culture (Bowman, 2008). All of my writings are infused with this post-structuralist concept or paradigm.

[7] Key structuralists such as Derrida and Spivak have both discussed the ‘irreducible metaphoricity’ of notions such as ‘structure’ and ‘discourse’. However, for an accessible discussion, see Hall’s ‘Cultural studies and its theoretical legacies’ (Hall, 1992).

[8] For a discussion, see Niels Akerstrøm Andersen’s Discursive Analytical Strategies: Understanding Foucault, Kosselleck, Laclau, Luhmann (Akerstrøm Andersen, 2003).

[9] See Mike Molasky’s contribution to The Martial Arts Studies Reader, forthcoming (Bowman, 2018).

[10] All quotations from Svinth are from email communication in June 2017.

[11] See Greg Downey ‘Domesticating an urban menace’ (Downey, 2002).

[12] See for example the work of Boretz (Boretz, 2011); also the article of Doug Farrer on martial arts and triads in Singapore, forthcoming in Martial Arts Studies issue 5, Winter 2017.

[13] See Wetzler’s argument (Wetzler, 2015).

[14] The 1918 item is part of a section called ‘To-Day’s Gossip’, about a ‘girl doctor’s market’, which reads: ‘Martial Art—Art and cabbages will flourish together that day, for next to the homely green stall will be one where Major Sir William Orpen, Major Augustus John and Captain Handley-Read will sell their produce. Do you recognise our martial artists?’

[15] The ident can be viewed here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5OVVm82R55M

[16] See Žižek (Žižek, 2001), Bowman on Žižek (Bowman, 2007b), and Benesch (Benesch, 2016).

[17] The time period squares with Žižek’s argument about the emergence of Taoism as the ‘spontaneous ideology of postmodern capitalism’ (Žižek, 2001).

December 18, 2017 at 2:26 am

Reblogged this on SMA bloggers.