Seeking Identity through the Martial Arts: The Case of Mexicanidad

By George Jennings

Jennings, G. (2017). Out of the labyrinth: The new Mexican martial arts riding the wave of Mexicanidad. Paper presented at the 3rd Martial Arts Studies International Conference, Cardiff University, UK, 12 July 2017.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Ben Judkins for his kind invitation to write another guest article for Kung Fu Tea, and for his and Tara Judkins’ ever-sharp editing. I am also deeply grateful to the Xilam martial arts community for their continued support of my work and to the other pioneers of Mexican martial arts who have shown an inspirational level of martial artistry in their creativity and vision. Finally, thanks to Barbara Ibinarriaga and Lorenzo Pedrini for their thoughtful comments on an earlier version of this article.

Asking the “who are we?” question in martial arts

Portraits of grandmasters hung on the wall. Banners from countries far and wide. Rare book collections in home bookshelves and esoteric weaponry from a bygone age proudly displayed in racks. Yin-yang symbols on t-shirts and training bags. Lion heads collecting dust, but ready to be played during Chinese New Year festivities. These items all form pieces of the puzzle that help us as martial arts practitioners and aficionados understand ourselves, other people (and peoples) and cultures, and also discover what we can become. So, do the supposedly ‘intangible’ aspects of language, ritual, magic and a range of anthropologically fascinating phenomena. When adding these objects, ideas and actions together, by practicing, promoting and passing on the martial arts, one becomes part of something bigger: be it a historical lineage or an official international federation.

Despite the common connotation of martial arts with individualism and self-cultivation, there is a deep sense of connectedness with those in one’s school, wider association, body lineage, martial ancestors and eventual successors – a geographical, intercultural and historical link. Many researchers have found this in contemporary scenarios, from ‘going to Brazil’ in a physical, intentional or symbolic sense from Canada (Joseph, 2008) to Chinese martial arts practitioners feeling part of something widespread and historically rooted, and thus possessing a deep sense of responsibility to pass it onto the next generation and care for the art for a better society (Jennings, 2010).

The search for ethnic and national identity is nothing new in the world of martial arts. It has been a quest undertaken by governments, tribes, clans and individuals for centuries to find out the answer to the question, “who am I?” Or, as Otmar Weiss (2017) put it in an address to the European Association for the Sociology of Sport (EASS), “who are we?”

The modern Japanese (using the suffix –do) martial arts (Aikido, Judo, Karate-do, Kendo, etc.), for instance, are part of a wider nationalist project that developed prior to World War Two to fill a void left by the Meiji Restoration. This nationalist movement unified previously disconnected fighting systems under a shared militaristic and pedagogical ethos. And this continues.

The topic of identity has been a key theme within the recent martial arts studies literature. Researchers looking at systems as distinct as Gouren, the Breton form of wrestling (Nardini, 2016), the Venezuelan stick and machete art of Juego de Garrote (Ryan, 2016) and the practice of embodying Brazil in British Capoeira (Delamont, Stephens and Campos, 2017) have all commented on this problem. The Chinese martial arts are no exception, with the development of the so-called northern and southern schools of Kung Fu, the forging of Cantonese and Hongkongese identities and also hybrid senses of identity through the martial arts cinema and their portrayal of folk heroes such as Wong Fei Hung, Ip Man and, of course, Bruce Lee (topics discussed at length here at Kung Fu Tea).

On the other side of the world, Mexican national identity is also expressed in its physical culture: the toughness and success of their professional boxers; the surreal and spectacular Lucha Libre (free wrestling); the bravado and elegance of the charreria on horseback, and the daring cliff divers of Acapulco all illustrate a national unification while at the same time addressing questions of local and regional identities: who are the Mexicans and what makes them unique? Cultural products such as tequila, the exquisite gastronomy and festivals such as the famous Day of the Dead all offer other insights into the past, present and future expression of “Mexicanness” – a concept hereafter referred to as Mexicanidad.

Yet since the conquest in 1521, the uniqueness of Mexican fighting systems as derived from their Mesoamerican basis has disappeared. More recently it has given way to the influence of the aforementioned Asian systems. However, in central Mexico during the 1990s, several pioneering martial artists developed new systems of combat to address this perceived lack of a unique martial-warrior identity. They expressed their claims, ideals and values in social media explored here.

This essay follows from the 2017 Martial Arts Studies Conference, where I presented a paper within the “Narratives” stream entitled “Out of the Labyrinth: The New Mexican Martial Arts Riding the Wave of Mexicanidad” (Jennings, 2017). I feel very fortunate to have the opportunity to write to the readers for the second time (for the first, see my collaboration with Anu Vaittinen on learning Wing Chun in the age of YouTube ). Like many of you, I am also a practitioner of Chinese martial arts (Wing Chun more specifically), but in this essay I wish to introduce you to a different set of fighting arts from another part of the world that were envisioned during a period of increasing national unrest, postcolonial intellectualism, indigenous pride and opportunities for entrepreneurial creativity. As you read about Mexico, its postcolonial era, the martial arts pioneers and the ancient Mesoamerican warriors they are inspired by and wish to emulate, I hope you are able to draw parallels with your own martial art system, current national identity or those of your ancestors.

The analysis begins with a consideration of the concept of identity and the action of identification along with the related inclusion and exclusion that go with this form of (dis)association. Using the framework of Mexican cultural critic Octavio Paz (1985) in his landmark series of essays, The Labyrinth of Solitude, I explore the case of Mexican history, and the many ways it has shaped how Mexicans see themselves in relation to their ancestors, their conquerors and colonisers and later the wider world. This is an effort to understand the concept (and movement) of Mexicanidad: the unique characteristics of being Mexican.

I then move to examine the discourses of identity communicated to the general public in the official online media of the emerging Mexican martial arts of Xilam, Pok-at-Tok, Tae Lama and SUCEM. They represent a diversity of styles that display the essence of Mexicanidad. Finally, the essay turns to a wider discussion of how these styles generate meaning beyond the current territory of what is now known as Mexico. The quest for identity involves more than ourselves and thus ‘the others’, leaving the reader to ponder on their own nation, personal identity and shifting sense of belonging.

Mexicanidad: Getting lost in the labyrinth of history

Many new and postcolonial nations have the opportunity to develop and express unique senses of identity. This search for one’s self is not simple, and it could be described as a confusing labyrinth with many optional routes and decisions to make. In 1950, 40 years after the Mexican Revolution, the Mexican poet and cultural critic Octavio Paz published a treatise of essays on Mexican culture and identity. In the Labyrinth of Solitude, Paz explored the boundaries of being Mexican in a cultural, geographical and historical sense. He offered an insight into a country still in its infancy, having been founded as an independent state in 1821. Starting with the Pachucos (now referred to as Chicanos), those Mexican-Americans living north of the border, Paz examined the sense of othering: that these people where neither Mexican nor U.S. citizens, and found acceptance among themselves. The ‘other’ here is someone who is different in look, background, speech and manner. Yet the other could be ‘you’ in the past or even the ‘you’ of the future. Continuing with a cultural critique of the general tensions, he then examines gender relations in Mexico (machismo) and the impact of malinchisma – the reverence of foreigners in post-colonial Mexico by the foreign-loving malinchistas.

Taking a historical approach, Paz then studies the centralised power of the Aztec (Mexica) and their influence in the central capital of Mexico-Tenochtitlan prior to the conquest. In a way colonisation continued this centralization of power, but only by completely destroying the pre-existing military and infrastructure. The (re)development of Mesoamerican warrior traditions is interesting given this historical structure.

There is one system, Yaomachtia, taught in Texas by a Mexican-American (Pachuco) martial arts instructor, Manuel Lozano who claimed to have inherited this art from the last living practitioner of the fighting style of the Mexica (a quick glimpse of this can be found at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lMGVjnshLRM). Although controversial and contested by aficionados of Mexican history (see http://newspaperrock.bluecorncomics.com/2011/01/origin-of-yaomachtia.html ), this inspiration and supposed connection to the Mexica is not unique. Xilam and SUCEM also emphasise the grandeur of this particular culture – the final expression of Mesoamerican civilisation. At the same time, the solitary warrior passing on the art to an apprentice might be impossible to prove, but perhaps the story is more important than the truth Much like Carlos Castaneda’s accounts of the mysterious warlock Don Juan (Castaneda, 1969) such tales offer us ways of questioning everyday, taken-for-granted, reality.

The search for identity can be lonely and challenging. Paz coined the term “Labyrinth of Solitude” to show how humans are the only animal that feels and knows s/he is alone, and is thus part of his anthropological sensitivity to the human condition:

“Solitude, the feeling of and knowing oneself to be alone, detached from the world and attached to it at the same time, separated as such, is not an exclusive characteristic of the Mexican. All people, in one moment of their lives, feel alone; and moreover, all humans are alone. To live is to separate ourselves from what we were to intend to be what we are going to be, always a future stranger. Solitude is the ultimate source of the human condition. Humans are the only being that feels alone and the only one that looks for another[…]Humans are nostalgia and the search for communion. For that reason, every time one feels oneself, one feels the lack of another, like solitude.” (Paz, 1981 [1950], p. 211).

In order to construct our personal identity, we must first connect to other people to form communal identities (tribes, schools, clubs, Kung Fu ‘families’ and lineages, etc.) and also a historical and processual one that involves ongoing processes of learning, teaching, caring, curating, coaching, promoting, etc. The “intelligence” of intellectuals and artists are important here, as Paz devoted a chapter on the Mexicans whose murals, portraits and poetry contributed to national identity. The martial arts, as arts in their own right, also contribute to a sense of national identity that grew from the independence movement to the revolution. It is as Chavarria (1971) muses on The Labyrinth of Solitude:

“One of the salient characteristics of twentieth century Mexican art and intellectual history has been preoccupation with the problem of national identity, or, put in another fashion, with the problem of defining lo mexicano. Most commonly, concern for lo mexicano and mexicanidad has been associated with the Mexican Revolution. The generally accepted assumption is that inasmuch as the Mexican Revolution was a revolution without ideology, it was not until Mexicans began questioning the meaning of their revolution that they asked – what are we? Who are we? Yet, the volume and importance of the intellectual and artistic production of the post- revolutionary period notwithstanding, it is certainly true that Mexicans were concerned with the problem of national identity even before 1910.”

(Chavarria, 1971, p. 381).

Essentially, this Mexicanidad is a sense of Mexicanness: it is what makes Mexico and Mexicans unique. However, from her ethnographic work on the “pre-Hispanic” conchero dancers in Mexico City, anthropologist Rostras (2002, 2009) explains “’Mexicanidad’ is not so much a struggle for mainstream political power as a proto-nationalistic ‘indianist’ movement, whose supporters are predominantly socially marginalized young males of Mexico City (and elsewhere)” (Rostras, 2002). It is thus both a concept and a sociopolitical movement – a wave which many social groups can ride in their own unique fashion, in unison or alone. Some might follow the pre-Hispanic movement of continuing the surviving Mesoamerican civilization (advocated by Bonfil Batalla, 1996), while others feel a sense of in-betweenness: “Caught by their dilemma of rejecting and accepting both metropolitan (Euro-American) and indigenous cultures” (Kelly Luciani, 2016, p. 9).

Of course, like all theories and texts, The Labyrinth of Solitude has its limitations. Despite many new editions, there are some elements of Mexican culture and history that are overlooked. Paz did not pay attention to physical culture such as dance, games, sport and fitness and physical activity. These are what the late Henning Eichberg (1998) termed ‘body cultures’, the expression of identity in certain spaces through human movement – with the martial arts being particularly interesting cases for exploring ritual, dress, gestures, interactions, forms of movement and use of terrain, objects and infrastructure.

Meanwhile, the influence of Asian cultures (in this case through their martial arts) is something that could have been examined beyond the ‘other’ influential and dominating cultures of the Spanish, French and Americans. The Mexicanidad outlined here can be seen in the colourful dresses of indigenous peoples, their handcraft and regional artisanal products, as well as the unique body cultures that Mexico has to offer, which extend beyond the existing and government-recognised native wrestling systems among the Raramuri people in Chihuahua (the Lucha Tarahumara) and the Zapotec people in Oaxaca (Chupa Porrazo).

Engaging with the new martial arts of postcolonial Mexico

Here I examine the emerging Mexican martial arts that form part of my exploration of Mexicanidad body cultures (Jennings, 2015, 2016, forthcoming 2018, forthcoming) – an ethnography and four case studies planned to be condensed in a monograph. The four systems of Xilam, Pak-at-Tok, SUCEM and Tae Lama were all founded in the 1990s by experienced Mexican martial artists with a vision for uniqueness and a mission to fill a void left in Mexican physical culture by malinchista views of the oriental martial arts. By definition of their (post)modern foundation, they are not pre-Hispanic (that being the period prior to Spanish contact around 1519). With influence from the United States and the global martial arts industry, they are also not Mexican in an isolated sense. Rather, these systems exist within a martial arts community that was initially dominated by East Asian martial arts such as Karate, Kung Fu, Judo and others, many of which have been compared with them on a technical sense.

The Mexicanidad of these martial arts is not to be found in the origins of their selected ‘techniques of the body’ (Mauss, 1968[1934]), but rather in the uniforms, language, rituals, customs, games and interactions that give them a Mexican look, sound, taste and flavour. Like all art forms, they are the product on an artist, or group of artists, that produced something unique. As such, I explore each of them with help from the official media in which these martial arts associations promote themselves to the wider Mexican community and position themselves within the complex pre-existing martial arts industry.

Xilam

Xilam means “to peel away the skin” in Maya, and is intended to slowly strip away the external barriers surrounding a person in order to find and transcend themselves. It is the first Mexican martial art created upon the basis of pre-Hispanic culture and philosophy, and stresses a holistic form of personal and shared development. According to their official website:

Xilam is based on the history dating back thousands of years, having its origin in the pre-Hispanic peoples transcending to our days as discipline, philosophy, spiritual and ceremonial mysticism, such characteristics that combine with today’s influences to form a Mexican Martial Art System.

Xilam is a system for personal development which takes into account the faculties that a human being possesses, specifically willpower, emotion, intelligence and consciousness.

Xilam was instigated by Marisela Ugalde and her former husband (both experienced practitioners and teachers of Kung Fu, Kempo, Judo, Karate and Lima Lama) in the 1980s and formally registered in 1992. After enjoying a brief period of success in the United States, especially among Mexican-American enthusiasts, the art returned to its homeland in Mexico City. Marisela continued to develop the philosophical basis of these practices from the Mexica worldview (outlined in Maffie, 2014), oral tradition from her mentor, the conchero dancer and indigenist guru Andres Segura, and continued academic collaboration and independent research into artefacts and other objects of heritage including carvings and murals. The Mexicanidad is expressed within this fighting system through the use of terminology in the native Nahuatl, Maya, Zapotec and occasionally, Mixtec, languages. It is also shown through the animals used in the structure of the system – the seven levels of snake, eagle, ocelotl, monkey, deer, iguana and armadillo. The movements are based on the Aztec calendar, and there are also complimentary classes in pre-Hispanic dance and Maya yoga, as well as corresponding services in Aztec astrology. Finally, advanced practitioners are able to wield pre-Hispanic weaponry and wear headdresses and other gear in demonstrations that evoke scenes of ritual and dance.

Pak-at-Tok

Similar to Xilam, Pak-at-Tok is also inspired by the Mesoamerican warriors, aiming to recover lost warrior traditions. Overtly emphasizing self-defence rather than spiritual development, Pak-at-Tok focuses on realistic training for hand-to-hand combat and against an armed opponent. It does not use weapons, and like Xilam, uses a modern uniform for its regular training: one commonplace in Asian martial arts, with belts and gi-like attire. Practised further north of Mexico City in Nayarit, Pak-at-Tok was developed by the martial arts veteran and linguist Adán Rocha, who claims that the art is purely influenced by evidence of pre-Hispanic fighting systems and is undiluted by Asian combat styles. Importantly, Rocha showed special interest in the female students who have passed through his school at a time when civil unrest and femicide were rife in the northern areas of Mexico.

POK-AT-TOK is the only system of self-defence that is totally Mexican, and that is was not derived from other martial arts. Furthermore, it is the only Mexican art recognised as such by the main martial arts federations[…]

POK-AT-TOK was inspired by a lengthy investigation in which he undertook, analysing hand-to-hand combat postures in collections of pre-Hispanic clay figures available in books and in museums. Dr. Rocha is a great connoisseur of other martial arts such as Okinawan Gojo Ryu Karate, in which he obtained a black belt back in 1972, and also the Lima Lama system, in which he obtained a fourth degree black belt; however, he comments that he took special care not to include a single technical element that could be derived from those systems to create the structure of defence and attack of POK-AT-TOK.

SUCEM

According to its founder and leader, Jesús Díaz, SUCEM is a “combat sport”. It overtly uses techniques from mixed martial arts (MMA), boxing and kickboxing for ring combat and in other arenas such as cages and octagons. It readily uses modern scientific training approaches to increase the fighting capacity of its athletic practitioners. Its statements seem to emphasize the male-dominated nature of the group, SUCEM calls for those Mexicans who identify themselves as possessing “warrior blood” to join the “men without limits.”

With a structured instructor programme and clear levels, including the jaguar and eagle warriors, SUCEM has moved on from its humble origins in a small town in Veracruz. It can now be found nationwide. Differentiating itself within the surge of MMA, SUCEM has added a distinct Mexican character in its head gear (akin to these Aztec warriors) and clubs and shields which are modified for safe competitive combat (rather than the original obsidian swords capable of lethal blows and cuts). They explain online:

Universal System for Extreme Combat of Mexico is a Mexican martial art constituted as a civil association that has the main objective to recover the pre-Hispanic culture of Mexico in the sporting environment; this is thanks to the fact that in our culture there is evidence that we were great combatants, such as in hand-to-hand encounters and combat with weapons; we have managed to found its sporting functionality in a scientific and pedagogical form and adopt it for competition in different modern disciplines such as boxing, kick boxing, grappling and MMA.

[…]we adopt a unique identity like that seen in other countries and aim to achieve a teaching of this in cultural, sporting and educational institutions at national and international levels.

Tae Lama

Finally, Tae Lama also admits to using non-Mexican techniques of the body through the fusion of Korean Taekwondo with Polynesian Lima Lama. With its hybrid name, which is also akin to a Nahuatl term meaning “warrior with wisdom”, Tae Lama promotes the indigenous language of central Mexico (once spoken by the Mexica), Nahuatl. Although they use East Asian uniforms like Pok-at-Tok, Tae Lama practitioners have Mexican style belts with intricate designs that are akin to native handcraft famous throughout Mexico. However, from an assessment of its official media communications, the mission of this art is not to promote Mexican culture, but to advance the martial arts through what their promotors claim is an evolution of martial arts for effective self-defence combined with a sophisticated philosophy – as illustrated in their blog:

The base of the current system is the combination of four styles of combat: LimaLama, Taekwondo, Aikido, boxing, and indigenous fights or street fighting.

It has philosophy and rules; it is the most complete Art of Defence that is practised these days.

(tae-lama.blogspot.co.uk)

Taken together, the expressions of Mexicanidad can be summarized in the table below:

From these four distinct arts – the most visible in social media and online – we can see that the quest for identity is taking very different paths. There may be other systems being created as I write, and others that remain in the shadows from the public eye, passed between master and apprentice. All of these systems suggest how investigations of the Mesoamerican past shape the possible future of the modern country of Mexico. Each of the arts finds a sense of Mexican identity in the country’s unique heritage: its many languages (there are 64 language groups), ethnic tribes, past civilisations, craft and patchwork, its animals and ecosystems, its materials and also its philosophy and related physical culture. In short, these martial arts act as an evolving microcosm of Mexico itself.

Out of the labyrinth: Finding and building identity through the martial arts

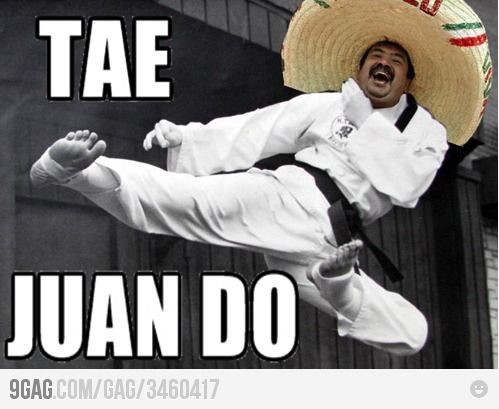

The quest for identity is not unique to the Mexican case or that of new nations and ethnic groups. Martial arts have an important role to play in the quest for self- (and other) understanding through their connections with language, symbols, movements, places, rituals, weaponry and native objects. Some countries (such as China) and regions (such as Guangzhong and Hong Kong) are tied to an image of sword-wielding, deadly martial artists. Others are associated with a different set of body cultures. The lifelong and intergenerational search for identity and meaning is a serious matter – perhaps not quite the life and death struggle that forged martial arts – but enough that it can become the pun of jokes, such as the one below:

We all know, as martial arts advocates and scholars, that it can be great fun partaking in and talking about martial arts, and are aware that many jokes can be made of cultural stereotypes. There is joy, laugher and creativity in how we learn to fight, express our culture and interact with other people. The above meme on “Taejuando” is one of many publicly mediated jokes on the non-existence of a Mexican martial art, and the seemingly trivial nature of such a possibility. Yet beyond the stereotypes of the moustachioed man with the sombrero – an image stamped into public consciousness thanks to photographs of revolucionario soldiers from the Mexican Revolution – there is actually a great variety of Mexican martial arts that show both creativity and artistry. They are using social media such as Facebook, memes, YouTube, Google Plus and many other professional and open-access platforms to share their philosophy, embodied practices and pedagogical strategies, and express what they see as unique to the Mexican warrior and martial identity – an identity that seemed to be missing among the plethora of artistic, musical and sporting options offered by the broader body cultures.

The systems of Xilam, SUCEM, Pok-at-Tok and Tae Lama are different in their structure, organisation, discourse, use of symbolism and language, but are united by a quest for Mexicanidad among the nation’s martial arts. They are four examples of postcolonial martial arts developed by seasoned martial artists in isolation from each other. Although they do not work in unison under a governing body, or even openly acknowledge each other’s existence and achievements, they do form part of the concept and movement of Mexicanidad: contributing to the tide of Mexican ingenuity and the issue of “creation.” This is a key word in the origin, evolution and survival of martial arts, seen by the likes of Judkins and Nielson (2015) to offer a way out of the solitary labyrinth that is the search for identity. Martial arts are one path to do this; they are about fighting, defense and war, which highlights the boundaries of groups and nations. Yet they are also about artistic creation and expression in the sense of individual flair. Much like a chef adding a twist to a Mexican classic, martial arts pioneers, their students and wider communities are forming small parts of the tide of indigenous, mestizo (mixed European and indigenous) and multicultural identities that explore the notion of being a warrior during a time of peace and instability.

Writers like Octavio Paz used words to express this rather than physical action, being part of a literary culture that can influence body cultures. The pen is their sword and argument is their shield. To close this article, I would like to return to the words of Paz (2000), who, when interviewed fifty years after the original publication of Labyrinth of Solitude, had this to say:

“My act was an interrogation that linked me to history’s unconscious process, that is, to the quest that forms the basis of historical movement. My interrogation inserted me into the quest, made me part of it: thus what had begun as a private meditation turned into a thinking about Mexican history. This thinking took the shape of a question not only about its origins—where and when did the conflict start – but also about the meaning of the quest that is Mexican history (and every- body else’s history).” (Paz, 2000).

And finally, to summarize the main message of this widely-known text (and, indeed, my own article):

“We sought ourselves, and found the others.” (Paz, 2000).

These ‘others’ might be our imagined warrior ancestors, our potential opponents “in the street”, our ideal martial artist envisaged from Kung Fu and Jianghu movies, or the very person one wishes to be in the future: the potential self. Past, present and possible futures collide when dealing with identities, and I stress the plural: identities, for we are always many things at the same time, and hold multiple meanings for these others, too. I leave it to the readers to decide who they are, who they belong to and who they imagine themselves to be in the future. The readers, researchers and reflective practitioners might benefit from examining theories of the country and culture in question – a theme for another day and another battle in martial arts studies.

References

Bonfil Batalla, G. (1996). Mexico profundo: Reclaiming civilisation (trans. P.A. Dennis). Austin: University of Texas Press.

Castaneda, C. (1969). The teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui way of knowledge. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Chavarria, J. (1971). A brief inquiry into Octavio Paz’s Laberinto of Mexicanidad. The Americas, 27(4), 381-388.

Delamont, S., Stephens, N. & Campos, C. (2017). Embodying Brazil: An Ethnography of Diasporic Capoeira. London: Routledge.

Eichberg, H. (1998). Body cultures: Essays on sport, space and identity. London: Routledge.

Jennings, G. (Forthcoming). Aspects of Mexican sexuality in the martial art of Xilam. In J. Piedra (Ed.), LGBTIQ people in Latin American sport. New York: Springer.

Jennings, G. (Forthcoming 2018). Messy research positioning and changing forms of ethnography: Reflections from a study of a Mexican martial art. In A. Plows (Ed.) Messy ethnographies. Wilmington, DE: Vernon Press.

Jennings, G. (2017). Out of the labyrinth: The new Mexican martial arts riding the wave of Mexicanidad. 3rd Martial Arts Studies International Conference, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK, 12 July 2017.

Jennings, G. (2016). Ancient wisdom, modern warriors: The (re)invention of a warrior tradition in Xilam. Martial Arts Studies, 2, 59-70.

Jennings, G. (2015). Mexican female warriors: The case of maestra Marisela Ugalde, founder of Xilam. In A. Channon & C. Matthews (Eds.), Women Warriors: International Perspectives on Women in Combat Sports (pp. 119-134). London: Palgrave MacMillan.

Jennings, G. (2010). Fighters, thinkers and shared cultivation: Experiencing transformation through the long-term practice of traditionalist Chinese martial arts. Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Exeter, UK.

Jennings, G. & Vaittinen, A. (2016). Wing Chun in the age of YouTube. In Kung Fu Tea: Chinese Martial Arts Studies. https://chinesemartialstudies.com/2016/09/08/multimedia-wing-chun-learning-and-practice-in-the-age-of-youtube/

Joseph, J. (2008). ‘Going to Brazil’: Transnational and corporeal movements of a Canadian-Brazilian martial arts community. Global Networks, 8(2), 194-213.

Judkins, B. & Nielson, J. (2015). The creation of Wing Chun: A social history of the southern Chinese martial arts. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Kelly Luciani, J.A. (2016). About anti-mestizaje. Universidade Federal de Parana: Species. Maffie, J. (2014). Aztec Philosophy: Understanding a World in Motion. University of Colorado Press.

Mauss, M. (1968 [1934]). Techniques of the body. In Marcel Mauss, Sociologie et Anthropologie (with introduction by Claude Levi-Strauss), 4th edition (pp. 364-386). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Nardini, D. (2016). Gouren, la lottabretone. Etnografia de unatradizionsportiva.Milan: Documenta.

Pok at Tok brand link: http://buildingabrandonline.com/ExistirConCalidad/defensa-personal-pok-at-tok-arte-marcial-100-por-ciento-mexicano/

Paz, O. (2000). How and why I wrote the Labyrinth of Solitude: An Elucidation. Hopscotch: A Cultural Review, 2(1), 60-71.

Paz, O. (1981[1950]). The labyrinth of solitude – The other Mexico – Return to the labyrinth of solitude – Mexico and the United States – The philanthropic ogre (trans. L. Kemp, Y. Milos and R. Phillips Belash). New York: The Grove Press.

Rostras, S. (2009). Carrying the word: The concheros dance in Mexico City. University Press of Colorado.

Rostras, S. (2002). ‘Mexicanidad’: The resurgence of the Indian in popular Mexican nationalism. Cambridge Journal of Anthropology, 23(1), 20-38.

Ryan, M.J. (2016). Venezuelan stick fighting: The civilizing process in martial arts. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

SUCEM official website: http://www.sucem.com.mx Last accessed 10.07.17

Tae Lama official blog: http://tae-lama.blogspot.co.uk Last accessed 08.07.17

Weiss, O. (2017). Keynote address: Sport and identity. The 14thEuropean Association for the Sociology of Sport Conference, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic, June 14th 2017.

Xilam official website: http://www.xilam.org Last accessed 08.07.17

About the author

Dr. George Jennings is a lecturer in sport sociology / physical culture at Cardiff Metropolitan University, Wales, UK. He holds a longstanding interest in the study of martial arts cultures, pedagogies and philosophies, and has published academic articles, book chapters and blog entries pertaining to ageing, embodiment, environment, film, gender, philosophy, religion and violence. His previous work looked at traditionalist Chinese martial arts as transformative practices in Britain, and later resided in Mexico from 2011 to 2016, where he investigated the emerging Mexican martial art of Xilam. Striving for a balance between academic inquiry and public engagement, whilst galvanising the idea of martial arts studies, George is currently calling for an interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary study of martial arts and health.

oOo

If you enjoyed this essay you might also want to read: Venezuelan Stick Fighting: What can we learn from the modernization of a vernacular fighting system?

oOo

1 Pingback