Confronting the Boxers

It is probably an irony that I have written so little on the Boxer Uprising during my casual and academic discussion of the martial arts. It was a chance encounter with the Boxers some years ago as I was exploring the connection between religiously generated social capital and violence that first convinced me to take a closer look at the Chinese martial arts as a possible research area. Still, it has been a slow return to a case that first inspired me.

There are multiple reasons for this. As my research progressed I found myself more drawn to the Republic period. The ill-fated Boxers of Shandong sit as a perpetual prologue to most of the questions that I ask. Further, my practical interests in Wing Chun led me to focus on Guangdong, which was about as far away from the events of 1900 as one could get while remaining within China.

It may also be that I am somewhat uncomfortable with this historical event. That feeling is also multi-faceted. The Boxers are often portrayed (even in historical sources that should know better) as an embodiment of “traditional” Chinese culture. Yet their unique combination of martial arts, ritual, theater, invulnerability and sorcery was seen by their contemporaries as being dangerous precisely because it was an innovation. Even that statement requires quick clarification. There was nothing new about martial arts, war magic or theater. And these things had always been mixed to one degree or another (much to the consternation of the Republic era nationalists and martial arts reformers). Yet the way in which these forces came together in northern China during 1899 and 1900 hit the region, already weakened by drought and social upheaval, like a wildfire.

Though destructive, such fires also have a way of quickly burning out. While Western discussions of the event tend to focus on suffering within the foreign military (David J. Silbey), or the diplomatic and missionary communities (Diana Preston), Paul A Cohen, in his groundbreaking History in Three Keys reminds us that these losses were dwarfed by the tens of thousands of deaths (most entirely senseless), and immense deprivations, experienced by the region’s civilian Chinese population. It is entirely possible to read the entire conflict as a civil dispute between two marginal groups in local society (Christian converts and a certain class of loosely organized poor peasants with an interest in martial arts) that spun out of control before being co-opted by larger geo-political actors.

Dealing with these events in a historically responsible way means addressing the enormity of the suffering and human loss that they unleashed. It also necessitates taking a closer look at the Boxers themselves and asking difficult questions. Should we think of these individuals as martial artists? How must our (often narrow and modern) understanding of “martial arts” change to accommodate their magical practices and spiritual beliefs? Under what circumstances do the martial arts, a set of practices that many of us are emotionally attached to, become a threat to social stability? Are there lessons to be learned about the role of the martial arts in spreading violence like a contagion that we are turning away from? If it is really true that the martial arts are fundamentally peaceful (a proposition that I find doubtful no matter how frequently it is repeated), what went wrong in this case?

It is easy for current practitioners of the Chinese hand combat systems to distance themselves from these issues precisely because reformers spent much of the 1910s-1940s systematically redefining, rationalizing and modernizing their (supposedly still traditional) practices precisely to insulate them from such accusations coming from modernizers within Chinese society. In practice that meant distancing these practices from their roots in rural society, “superstitious beliefs” and any association with opera. One suspects that it is not a coincidence that even dedicated historians find the subtle social relationships between the martial arts, opera and ritual practice difficult to reconstruct. Even more telling is how few people ask the question at all. Despite the almost subconscious habit of appending the term “traditional” to every written occurrence of the phrase “Chinese martial arts”, in practice most of us are comfortable reading a very modern view of these practices back through the centuries.

Given that my personal research interests have focused on later periods, and have been grounded in the distinct local culture of the Pearl River Delta region, it never seemed like the right time to delve into these questions. Nevertheless, research programs evolve.

My current “Kung Fu Diplomacy” project begins with a discussion of how some in the West used the discussion of martial arts to establish an image of China that was advantageous to their cultural, economic and political agenda. These discussions of the martial arts, while often framed in terms of popular culture, have sometimes had important implications for both how we understand our selves and interact with the wider world. Nor can one fully understand how this process unfolds, or the foundation on which our current engagement with the Chinese martial arts rests, without coming to terms with the Boxer Uprising.

Boxers in the Popular Press

The first step in reconstructing the image of the Boxers in the Western imagination is to go back and examine the various ways in which they were discussed in the popular press during the violent and confusing summer of 1900. For Western readers in London, New York, or even Shanghai, confusion as to what was happening in Northern China was probably the most memorable aspect of the period. Paul Cohen dedicated an entire section of his study to the topic of “rumors.” One imagines that by the autumn of 1900 any Western newspaper reader would have sympathized with his interest in the topic.

During the second half of July even reputable papers like the New York Times were reporting graphic accounts of the various ways in which crowds of Boxers had overrun the foreign legation, murdered its inhabitants, and paraded their mutilated corpses through the streets. Obviously, no such thing ever happened. The legation was successfully defended until reinforcement arrived and seized control of Beijing itself. Yet in the final weeks of July newspaper readers would be treated to one independent account after another, each purporting to be the real story of the massacre of white men, women and children at the hands of a literal Boxer army. I can think of no other group who died so many deaths, day after day, on the front pages of the world’s leading papers. The irony of the situation is that not only did most of the legation residents survive, but that death in Beijing was disproportionately inflicted upon Chinese civilians who were neither soldiers nor Boxers.

Such failures of journalism notwithstanding, the Boxer Rebellion was one of the most important media events of the first decade of the 20th century. Newspapers carried countless harrowing accounts of attacks on outlying missions and the murder of Chinese Christian converts. Later announcements that the armies of rival imperialist powers were combining forces to fight the rising tide of disorder captured the imaginations of those with more humanitarian passions. Meanwhile diplomats and businessmen wondered what this meant for the balance of power in Asia, and how long the alliance could possibly hold. At its height, the Chinese Boxers even managed to upstage a US presidential election.

It might be natural to assume that this volume of press coverage would lead to a growing curiosity about the Boxers themselves. After all, if it was true that the Chinese martial arts were basically unknown in the West (a proposition I find dubious), one would think that newspapers would be obligated to fill their readers in on the emergence of a fearsome new threat to Western values and influence in China. That is what I expected to find as I undertook a systematic survey of newspapers (including the New York Times and The Times (of London), and popular publications (The National Geographic, the Illustrated London News and The Sphere among others).

What I actually found (in addition to an astonishing tangle of rumors and false reports) was somewhat different. During the spring of 1900 the lines of communication with Northern China were open and so the quality of information being reported was still good. As the violence escalated in the countryside reports of Boxers attacks became more common. Yet the general assumption seems to have been that anyone reading such accounts was already interested in China or Chinese culture, and thus needed no education as to what a “Boxer” was. While the specifics of this situation were new, the general outline of Chinese boxing was already firmly established (for at least this segment of the audience) and required no further explanation.

Nor can we really fault editors in this regard. While the claims of invulnerability being made by the Yihi Boxers were novel, the Chinese martial arts and traditional modes of hand combat had been discussed in some detail in the West for decades. J. G. Wood, one of the most popular writers of the era (and someone cited by a variety of other novelists and authors) discussed the traditional Japanese, Chinese and Indian combat methods at length in his best-selling (but unfortunately titled) The Uncivilized Races of All Men in All Countries. Given the centrality of large and fearsome swords in almost all early Boxer accounts (indeed, their association with the “Big Sword Society” of richer areas of Shandong was sometimes asserted), Western students of China would no doubt recall these memorable passages from Wood:

“Of swords the Chinese have an abundant variety. Some are single-handed swords, and there is one device by which two swords are carried in the same sheath and are used one in each hand. I have seen the two sword exercise performed, and can understand that, when opposed to any person not acquainted with the weapon, the Chinese swordsman would seem irresistible. But in spite of the two swords, which fly about the wielder’s head like the sails of a mill, and the agility with which the Chinese fencer leaps about and presents first one side and then the other to this antagonist, I cannot think but that any ordinary fencer would be able to keep himself out of reach, and also to get in his point, in spite of the whirling blades of the adversary.

Two-handed swords are much used. One of these weapons in my collection is five feet six inches in length, and weighs rather more than four pounds and a quarter. The blade is three feet in length and two inches in width. The thickness of metal at the hilt is a quarter of an inch near the hilt, diminishing slightly towards the point. The whole of the blade has a very slight curve. The handle is beautifully wrapped with narrow braid, so as to form an intricate pattern.

There is another weapon, the blade of which exactly resembles that of the two handed sword, but it is set at the end of a long handle some six or seven feet in length, so that, although it will inflict a fatal wound when it does strike an enemy, it is a most unmanageable implement, and must take so long for the bearer to recover himself, in case he misses his blow, that he would be quite at the mercy of an active antagonist.

Should they be victorious in battle, the Chinese are cruel conquerors, and are apt to inflict horrible tortures, not only upon their prisoners of war, but even upon the unoffending inhabitants of the vanquished land. They carry this love for torture even into civil life, and display a horrible ingenuity in producing the greatest suffering with the least apparent mean of inflicting it. For example, one of the ordinary punishments in China is the compulsory kneeling bare-legged on a coiled chain. This does not sound particularly dreadful but the agony that is caused in indescribably, especially as two officers stand by the sufferer and prevent him from seeking even a transient relief by shifting his posture. Broken crockery is sometimes substituted for the chain……”

J. G. Wood. 1876. The Uncivilized Races of All Men in All Countries. Vol. II. Hartford: the J. B. Burr Publishing Co. Chapter, CLIV China—continued. Warfare.—Chinese Swords. pp. 1434-1435.

Wood’s discussion in this case was driven by the Western fascination with the collecting and display of all sorts of ethnographic Weapons. Yet it is interesting to note the other ideas regarding the nature of Chinese martial arts that crept into Wood’s discussion. On the one hand the efficacy of these methods is questioned. Readers are assured that a western fencer, let alone a professional soldier, would be more than a match for any boxer, no matter how fascinating his armaments.

So why might a group cling to an ineffective combat system? Perhaps their obsession with the martial arts masked a propensity for sadism and cruelty. The fact that Wood’s discussion of traditional Chinese swords terminates in an extended discussion of torture (most of which has been omitted in the interests of brevity) would seem to indicate that he, and much of the reading public, saw these practices not so much as a set of skills to be mastered as a reflection of some sort of character defect on the part of the Chinese people. The Chinese martial arts, to put it slightly differently, were not “arts” at all. These were not rational and scientific practices (like Judo) that westerners might find interesting. They were instead a reflection of everything that was seen to be threatening about the Chinese nation.

As the summer wore on the frequency of Boxer discussions in the popular press escalated and editors became aware that what had been a niche story was now sitting on the front page and selling newspapers. As the readership for these accounts grew, so did the need to retroactively describe and explain the Boxer to a non-specialist audience. In a few cases papers like the New York Times printed frank admissions by American diplomats in China (or Chinese diplomats in the US) that the Yihi Boxers were a fundamentally new and not yet understood group. China was full of Secret Societies and voluntary associations and so simply noting that a group engaged in boxing did not really tell one very much about their motives, origins or potential actions.

More common were reprints of accounts by missionaries who had witnessed the build-up of the Boxers in various small towns. They tended to dwell on the “gymnastic exercises” and “military drill” practiced by the Boxers, as well as their belief in their own invulnerability to swords and rifle fire. In other cases experts in Chinese culture were called upon to explain the sudden emergence of the Boxer threat. Falling back on what was already known about Chinese martial artists and their association with secret societies, they tended to see the Boxers as simply another manifestation of the later. Chinese triads, and their revolutionary intentions, had been discussed in the Western press for at least two generations and were a popular topic. One could even read cheap novels on their exploits.

While it was acknowledged that the Boxer threat was new, the few explanations of the group that emerged tended to see it simply as an extension of what Westerners already believed about patterns of Chinese social violence. This resulted in a paradox that called out for a solution. If what was being seen related to well-known propensities in Chinese society, why did it emerge only in 1899-1900? How could the crisis be unlike any event in living memory, yet at the same time be deeply traditional?

Missionaries noted the role of the drought in the emergence of the Boxer threat and offered their own prayers for rain. Yet the role of the Western clergy in sparking the crisis did not go unnoticed in the West. Indeed, the missionaries seem to have had something of an image problem in both America and China in 1900. More secular commentators on Chinese matters laid much of the blame directly at the feat of Catholic missionaries and their propensity to meddle in local court cases. Protestants, while less egregious in their methods, were also seen as foolish as setting up missions that would be impossible to defend, or even evacuate, in case of trouble.

Later scholars such as Cohen and Esherick would discuss both factors at length. Yet the most common explanation offered at the time was simply that the Boxers were pawns. Rather than being independent actors with their own motivation, they had been set in motion by the Dowager Empress as part of a coordinated, multi-year, scheme to rid China of all foreign influence. While this explanation enjoys no historical support, it seems to have satisfied the greatest number of readers at the time.

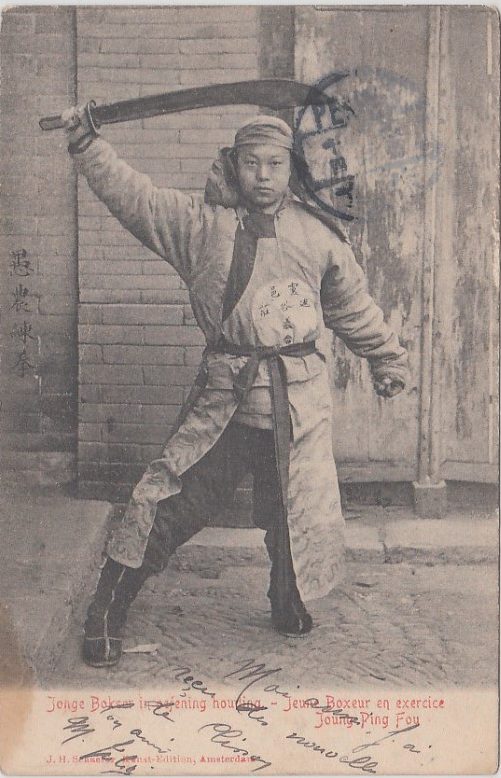

Boxers and the Invention of the Martial Arts Film

Though the public showed less curiosity than one might have expected regarding the origins and motivations of the Boxers, they were fascinated by questions of their physical appearance and behavior. The illustrated magazines of the period enjoyed a distinct advantage over the daily press since their engravings could illustrate this exotic threat, and therefore shape the image of the Chinese martial arts in the West. Images of Chinese soldiers, archaic weapons and seemingly impregnable fortresses filled the pages of many of these publications. These pictures were accompanied by vivid descriptions of the latest fighting outside of Beijing, or reports of Boxer massacres at remote missions.

Yet the emergence of new technologies ensured that magazines would not retain a monopoly on graphic depictions of Boxer violence. Film was still in a state of relative infancy when fighting first broke out late in 1899. The first public performance of a film had taken place in Paris in 1895, and most of the movies that were being produced between 1895 and 1899 were relatively simple set piece affairs featuring only one performer captured in a single static shot. Yet by the turn of the century filmmakers were striking out in new directions which would affect how the Western public encountered the Boxer Rebellion.

There seems to have been some competition between early film makers attempting to satisfying the public’s interest in these events. Perhaps the first of these films (though the timeline is a bit unclear) was Sagar Mitchell and James Kenyon’s “Boxer Attack on a Mission Outpost” in 1900. This short film lasted just under a minute and was shot as a single scene. It told a simple story in which a Western missionary greeted his wife and daughter as they head out. A second later they can be seen running back while the mission falls under attack by a mob of colorfully (if not authentically) dressed “Boxers” employing a mix of traditional weapons (including a Dadao) and clubs. The European missionary resists gamely with his cane (referencing turn of the century interest in the gentlemanly arts of self-defense), until a group of British soldiers appear and restore order through the use of superior firepower.

Mitchell and Kenyon’s film was following up on a previous hit which had focused on the (then ongoing) Boer War. While audiences almost certainly understood that the footage was staged, there seems to have been a great deal of enthusiasm for “realistic” recreations of these events. The most interesting aspect of this film is probably the appearance of Western cane fighting and a Chinese dadao in the same scene. This must have been the first time that Occidental and “Oriental” fighting skills were called upon to square off against one another on screen from the enjoyment of a paying audience.

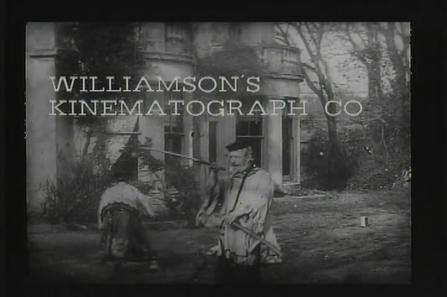

Mitchell and Kenyon were not the only directors looking to capture the essence of the Boxer Rebellion on film. Even more important, and certainly better known, is James Williamson’s “Attack on a China Mission”, also screened in 1900. Williamson’s film is in many ways the more ambitious of the two. Its original running time was probably close to two minutes, but in its current edited form we have only 1:15 worth of material.

The project was also notable for its technical complexity. It employed a cast of over 20 individuals (most of which were either British sailors or a Boxer mob) and attempted to tell a complex story through the four discrete shots and (the first ever) reverse angle cut. In this film Boxers break through a gate to assault a mission house. They are better armed than the previous group and came at the settlement with rifles, swords and clubs, with the aim of slaughtering its inhabitants and burning the place down. The missionary and his wife whisk multiple children inside, and he then returns to the yard to defend the settlement with his own firearm. The missionary is overwhelmed and killed by a Boxer armed with some sort of saber. The wife can then be seen calling for help from the balcony as the house begins to issue smoke. At that point a detachment of painfully well-ordered British sailors appear on the scene and begin to lay down fire, thereby preserving the honor of white womanhood in China. This last point appears to be a none too subtle subtext in both films.

This film was a pioneer in a number of respects. Employing a greater number of shots and camera angles to tell an engaging story was an innovation that helped to set the stage for a new era of plot-centric action films. Williamson also put his background as chemist to good use as he attempted to replicate gunshots, smoke and explosions in a way that would capture the audience’s attention. Yet he did not intend to tell a story about victory through technical superiority. Simply firing a gun was not enough to save his missionary as the Boxers were also well armed. It was the superior martial character and discipline of British troops, advancing in tight ranks (rather than the more “realistic” rush seen in Mitchell and Kenyon’s film) that won the day.

These two films were joined by at least one other, more mysterious, production titled “Beheading a Chinese Boxer.” This was the shortest and simplest of any of the productions. It showed a single Chinese captive being forced to kneel and then beheaded (again with what appears to be an authentic dadao). Identical execution scenes had been described in popular publications since the 1850s and were even shown on Western postcards. The actual staging of the execution is surprisingly realistic. Additionally, most of the surrounding soldiers carry red tasseled spears that would be immediately recognizable to any Sinophile in the audience. Special effects are again employed in the actual beheading, and the head itself is placed on a pike at the end of execution for good measure.

This shorter film is often attributed to Mitchell and Kenyon. It should be noted that their other production ends with the British forces seizing a single live captive. One wonders if we are witnessing his ultimate fate. Yet the BFI Player webpage states that there are questions regarding the accuracy of this attribution. Contemporary catalogs note that something resembling this film, and possibly produced by Pathé or Walter Gibbons, was distributed by Warwick Trading Company. Or this could indicate that there were at least four Boxer Rebellion films circulating in 1900 (that we know of), with three currently surviving.

Conclusion: The Boxers as a Familiar Foe

I recently had an opportunity to see a much more current documentary on the martial arts. It was a BBC production that discussed the introduction of the martial arts to the UK. Given that most such discussions focus on the US, I was very interested to see more of the European side of this story. Nor did it hurt that some friends and colleagues (including Stephen Chan and Paul Bowman) made appearances throughout.

The emphasis on the UK notwithstanding, I think that most American students of martial arts history would find the basic outline of story to be very recognizable. The Japanese martial arts (beginning with Jujitsu, and hybridized as Bartitsu) are first “discovered” in the West at the turn of the century. Judo is then popularized. Next, American servicemen in the Pacific return after being introduced to Karate. Finally, in the early 1970s the world hears (apparently for the first time) that there is thing called “Kung Fu.”

The outlines of the narrative are familiar, and in a certain sense they are true. A whole generation of youth and teenagers who did not previously know about the Chinese martial arts did discover them in the late 1960s and early 1970s. And Bruce Lee was absolutely instrumental in popularizing them (as well as all of the other Asian martial arts if we are being honest).

Yet as a historian I know that this simplified account leaves out quite a bit. And the story that is excluded is just as interesting as the one we typically choose to emphasize. For instance, when we focus on Bruce Lee introducing Kung Fu to rambunctious (mostly male) youth in the 1970s, we seem to conveniently forget about Sophia Delza and Gerda “Pytt” Geddes introducing a very different (and more female) demographic to Taijiquan in the 1950s. What is at stake when we tell one story to the exclusion of the others? When we discuss the absolute secrecy with which Chinatown residents in the US and the UK guarded their martial arts in the 1960s we forget the almost desperate attempts of China’s Republican government to promote their martial arts to the English speaking world (even showcasing them at the Olympics) during the 1930s and 1940s. Indeed, as far back as the 1860s Wood could write with authority about the Chinese martial arts demonstrations that he had witnessed…in London.

The story of the Western discovery of the Chinese martial arts that we most frequently tell is not wrong, but it is a partial picture. As students of martial arts studies, we need to ask not only whether this historical discourse is correct, but also what sort of social or cultural “work” it is currently doing.

When we remember the discovery of Bruce Lee, who specifically is the “we” in this equation? And who is being forgotten? When we put forward a narrative that privileges only a single aspect of the Chinese diaspora (supposedly secretive working class Chinatowns in London and San Francisco), what other elements of the Chinese community (often with very different, more nationalist, goals) are encouraged to fade into the background? Even if it is true that large numbers of people did not begin to practice to the Chinese martial arts until the 1970s or 1980s, might it be worth asking what previous generations thought about these practices? Or why they might not have been interested in pursuing them in one decade, but found new meanings in almost identical symbols in the next?

The Boxer Rebellion is interesting as it reminds us that, contrary to the dominant narrative, the Western public did not first encounter Chinese martial artists in the 1970s. Nor was Bruce Lee the first Chinese individual who appeared in Western popular culture who was physically dangerous and capable to defeating a white opponent. What was new was that this was no longer viewed as being as fundamentally threatening or as dangerous as it once would have been.

We must acknowledge the fact that the image of the Chinese martial artist has long stalked the Western imagination. Whether labeled a “sword dancer”, acrobat or boxer, the figure he or she has always been present. While their multiple meanings might have been recast by the post-war counter-culture movements, their origins are deeper. There might be no better evidence of this than the media explosion that accompanied the Boxer Rebellion.

Rather than agreeing that the portrayal of the traditional Chinese martial artists (however badly acted) on Western movie screens is a relatively new thing, imported from Hong Kong in the 1970s, what we instead see is that these images were instrumental in laying the groundwork for all modern action films. Indeed, colonial adventures in Africa and Asia gave us the genres of adventure stories that we still enjoy today. Rather than Asian identity becoming a foil against which Western notions of self and nationalism were shaped in the post-Vietnam War era, the same process can be seen at play in the 1850s, and again following the events of 1900.

A close examination of martial arts history shows that Chinese and Western identity have long been intertwined in a process that can only be described as mutually constitutive. This is not to imply that things have always been harmonious. The Boxer Rebellion was not only a paradigm defining moment in Chinese history, it is also critical for understanding questions of identity in the modern West as well.

oOo

If you enjoyed this you might also want to read: David Palmer on writing better martial arts history and understanding the sources of “Qi Cultivation” in modern Chinese popular culture.

oOo

March 24, 2017 at 8:50 pm

Reblogged this on SMA bloggers.

April 6, 2017 at 9:17 am

Here is an important resource that I just ran across. It will be of interest to anyone looking to do more research on the early Boxer Rebellion “Fakes.” See especially chapter 13:

https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/22650

July 9, 2017 at 10:27 pm

Does anyone know just what style of kung fu the Boxers practiced. I guess it was tang lang, being from Shandong but it is only a guess

July 10, 2017 at 3:30 am

Anyone know just what style of kung fu the Boxers practiced?