***For the Friday post we will be revisiting a classic (and very popular) article from the archives. I originally posted this essay almost two years ago and recently I have found myself thinking about it again. It will also be good to review as it introduces some concepts that are key to a larger project that I am working on at the moment. While I have completed most of the rough draft for an initial post on this topic I am still waiting on a few sources, and I don’t want to rush things. Hopefully it will be ready by next week. In the mean, time please enjoy this discussion of Bodhidharma and then take a quick look at the recommended post at the end. With both of them under your belt you should be well prepared for what is coming next.***

Introduction

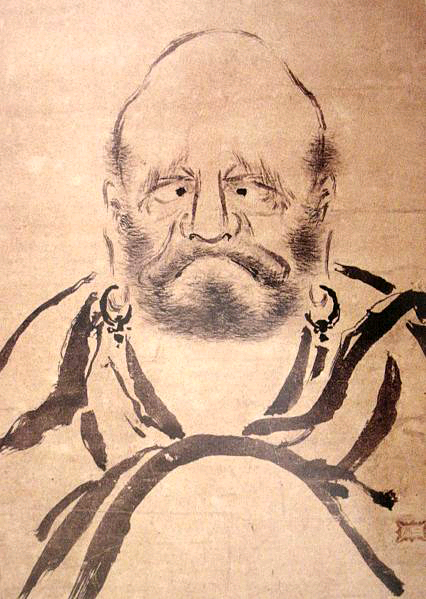

I was recently exchanging emails with a martial arts instructor and reader who suggested that I address the historical facts behind the “Bodhidharma myth.” This is a critical topic for anyone interested in either the historical or cultural aspects of Chinese martial studies. Bodhidharma is a shadowy figure. A Buddhist missionary to China, he is often credited with the importation of Chan Buddhism sometime in the 5th or 6th centuries.

As Meir Shahar and others have already pointed out it, is hard to take these claims literally. Chan Buddhism is an indigenous creation which reflects then current trends and debates within China’s social environment, not India’s. It would not even arise as a religious movement until more than a century after the “First Patriarch’s” death, though there are some who have argued that his teachings may have been important to the eventual emergence of Chan.

Even Bodhidharma’s origins remain a mystery. Chinese tradition holds that he was a native of India. Japanese schools, on the other hand, assert that he was a Persian.

Of course the venerable patriarch also has a longstanding association with the Shaolin Temple in Dengfeng county of Henan province. Later myths, first appearing in the late 17th century (and still promoted by many modern martial artists today) claim that he brought some sort of unique fighting system to Shaolin which has subsequently become the basis of all traditional Kung Fu.

Even before the emergence of this story Bodhidharma had a complicated and evolving relationship with the region surrounding Shaolin. As Shahar relates, none of the earliest records of the temple mention his presence. It is not until after the advent of Chan Buddhism that he begins to make an appearance in retrospectively produced historical accounts. In the earliest stories he only visits the capital, then a few years later his journey takes him to Mt. Song. Only some years after that did accounts of him visiting Shaolin first appear. In short, while the Indian Saint has long been associated with the religious reputation of the Shaolin monastery, few scholars seem to accept the popular accounts of his life or teachings (all of which are anachronistic) at face value.

The stories of Bodhidharma teaching the Indian martial arts (or even Yoga like exercises) at Shaolin are, if anything, even more outlandish. The earliest religious myths associating him with Shaolin seem to date to the 8th century. The accounts linking him to the region’s martial arts do not make their first appearance until the start of the 17th century. Nor do the many Buddhist chronicles produced through the intervening years contain any hint that the wandering Indian genius was also a martial artist.

In short, stories linking Bodhidharma to the creation of the Chinese martial arts are clearly problematic. This is not a recent revelation. Practically every historian or student of Chinese religion to have looked at these issues has already debunked this legend. Douglas Wile, Stanley Henning, Dominic LaRochelle, Meir Shahar and a host of other have already pointed out the myriad of inconsistencies in these accounts.

As Henning reminds us, one of Tang Hao’s first contributions to the modern study of the Chinese martial arts in 1930 was to demolish the Shaolin-Bodhidharma connection. Shahar points out that even as early as the middle of the Qing dynasty, Chinese historical scholars and biographers were well aware that the central texts linking the Indian missionary to the martial arts were poorly executed forgeries, probably produced by “village masters” in the early decades of the 17th century.

So much has already been written on the historicity of Bodhidharma by so many other competent scholars that I was hesitant to jump into the fray. It is actually hard to imagine any Kung Fu legend that has been more frequently “debunked” than this one. It is not even a question of “modern research.” Almost from the day that this story first began to circulate during the Late Imperial period, well-educated historical and literary scholars knew that it was a forgery.

Still, if I have learned one thing during the course of my research, it is that the traditional Chinese martial arts community will never let “mere” history get in the way of a good story. And the Bodhidharma myth is just that. It’s a fascinating story that has remained in circulation for about 400 years. Nor has globalization and the easy availability of reliable historical sources slowed the spread of this myth. In fact, there are probably more people around the global who now “know” about Bodhidharma’s role in the creation of the martial arts than at any time in the past.

Given the mountains of evidence that we now have at our fingertips, why do modern martial artists, both in China and the west, still insist on linking the “Shaolin Arts” to an ancient Indian missionary? How is it that the numerous critiques of this legend, in the 18th, the 20th and 21st centuries, have had practically no impact on the growth and spread of this “folk history?”

It would seem redundant to recount in detail all of the arguments as to why the link between Bodhidharma and the Chinese martial arts is spurious. Anyone interested in reviewing this debate is more than welcome to check out practically anything ever written by Tang Hao, Stanley Henning or Meir Shahar. In my view the more interesting theoretical question is the odd persistence of this legend in modern martial arts folklore. Why is it that so many well-known martial artists continue to produce books and articles that all take this story for granted?

In order to get a better understanding of this phenomenon the following post begins by examining the first appearance of Bodhidharma in the martial arts literature of the early 17th century. Of special importance is the question of how this sage’s martial contributions came to be attached to (and accepted by) the monks of the Shaolin Monastery. While this figure had long been regarded as the founding patriarch of Shaolin’s transmission of Chan Buddhism, Shahar reminds us that his cooptation into the temple’s martial tradition was far from inevitable. In some ways it is even a bit puzzling.

The second section of this essay turns to the idea of “hyper-real religions.” This recently developed concept from the religious studies literature attempts to describe spiritual movements that are consciously founded on the basis of fictional texts. Jediism, a “new religious movement” that is based on George Lucas’ Star Wars film franchise, is a typically cited example of this sort of movement.

Hyper-reality, as a conceptual category, owes its existence to post-modern arguments about the nature of perception. Particularly important is Jean Baudrillard’s contention that culture is inherently a form of representation, or a “simulacra.”

Current scholarship tends to apply this idea to the various “post-modern” new religious movements that appear in the western world today. Nevertheless, this concept might help us to make sense of a number of puzzles in Chinese martial studies, including the odd persistence of the cult of Bodhidharma. I also suggest that certain structural similarities between the Ming-Qing transition period, the early 20th century, and the modern western world today, might help to explain why individuals in these three different epochs accept a story that is widely known to be fictional.

Bodhidharma and the Sinew Transformation Classic

The very first text to claim Bodhidharma as a martial arts master was the Sinew Transformation Classic. While historically spurious this work (according to Tang Hao and Meir Shahar) probably dates to 1624 in Zhejiang. The book is interesting for another reason as well. It is a good example of the multiple types of syncretism that became popular in late Ming thought. It also demonstrates that these traits, well documented among elites, were influencing patterns of belief and behavior in society’s more plebeian levels as well.

Most of this manual is dedicated to a series of “internal” (or neigong) exercises drawn from Daoist longevity practices. For our purposes the most interesting aspect of this work is its various introductory prefaces. In addition to giving us certain hints as to the text’s authorship, they also help to situate this book in late Ming popular culture.

Shahar has noted that the introductions to the Sinew Transformation Classic are typical of certain strands of late Ming thought in the degree to which they freely mix and draw from Confucianism, Buddhism and Daoism. All three of these religious and philosophical systems are seen as means to a similar end. Bodhidharma, a Buddhist saint, is introduced as the teacher of what is clearly a set of Daoist gymnastic exercises.

Still, there is another type of syncretism at play that is of more interest to students of martial studies. The pseudepigraphal authors of these prefaces are great generals from China’s distant past. Their testimony attest to the awesome power of the practices contained within the book. They leave the reader with no doubt that they attained their military and worldly success by following the qigong-esque exercises laid out in the manual. Yet at the same time they lament that they never pursued the equally potent “spiritual truths” contained in these sets. Readers are instructed to learn from their example, and to cultivate their spiritual powers as well.

Students of modern martial arts fiction might not find this sort of a creation narrative to be all that surprising. Yet as Shahar points out, this is the earliest manuscript we have that clearly states that the practice of a single set of physical exercises will lead to both martial and spiritual attainment (not to mention increased physical health).

This synthesis of interest around a single set of practices is incredibly important. The great popularity of this work and the exercises that it suggests indicates that this view found a ready audience. It is also the first foreshadowing that we have of trends within the hand combat community which would become more pronounced as the second half of the Qing dynasty wore on.

Still, there are some puzzles that need to be dealt with. To begin with, the prefaces of the Sinew Transformation Classic explicitly attribute these practices to Bodhidharma. That is not totally surprising. Other novels and texts dealing with various esoteric arts (including gymnastics) being produced in the late Ming also saw him as a teacher of mystical self-cultivation techniques. Interestingly most of these were associated with Daoism. In this way Bodhidharma, a Buddhist missionary, became an embodiment of the values behind late Ming syncretism. I think that it might also be fair to say that he became a symbol of a certain vision of Chinese cultural identity.

Yet this manuscript tradition tends to have a somewhat hostile view of the monks of Shaolin. It attributes what martial genius they have to their remembrance of these practices, but it also claims that they have lost the ability to read and understand the original text. They are, in essence, the inheritors of an empty practice. Readers of this text are promised that they will excel far beyond what the monks of Shaolin have achieved. So given the hostility of these texts, how did they, and the image of Bodhidharma as a martial teacher, come to be adopted into the Shaolin tradition of the 17th and 18th centuries?

A different, yet related, question has to do with the social transformation of this text in the wake of the Ming-Qing transition. A literary analysis of this work indicates that it was produced by an only marginally educated individual early in the 17th century. As such we can assume that it reflects a body of popular practice at that point in time.

Prior to the fall of the Ming dynasty few elites concerned themselves with the martial arts, and those that did (particularly the ones from military families) tended to focus on either weapons training or serious military service. Given the turbulent final years of the dynasty this emphasis makes a lot of sense.

The situation came to look very different in the years following the Qing rise to power. With the nation pacified military training was less pressing. At the same time, the Confucian educated social elites faced a series of serious existential challenges. What had gone wrong in both statecraft and social values at the end of the Ming dynasty? How had the Middle Kingdom been conquered? What value was there in Chinese society, and how should one go about rebuilding and strengthening it?

A new generation of educated students began to take a serious second look at martial and physical training during these years. But rather than going back to previous practices, they continued to push forward with the trends that had just been emerging at the start of the 17th century. Shahar contends that they were fascinated with the possibility of combining military, philosophical and medical training in one place, much as the Sinew Transformation Classic promised. It was during the middle years of the Qing dynasty that more educated elites began to seriously promote this work in both manuscript and printed editions.

This creates a paradox. Classically trained individuals might be enthusiastic about the ideas behind the text, but they were also the most likely to see through its highly problematic facade. In fact, Shahar reminds us that a number of Qing era researchers did conclude that the book was a forgery based on sound scholarship. Still, their efforts did not seem to have much of an impact on the spread of the legend.

Why would these educated individuals, who were at least likely to understand that they dealing with a fictional text, be willing to go along with it anyway? Likewise, why would the Shaolin monks, who probably knew more about Bodhidharma than any other group in China, have felt comfortable appropriating a work like this, and making its mythology part of their own religious heritage?

The answer seems to be that the symbolic value of the story of Bodhidharma displaced the patriarch’s historical legacy in the wake of the Ming-Qing transition and the existential crisis that it unleashed. At a time when individuals were doubting the reliability of the Chinese cultural tradition, and blaming the lax attitudes of the Ming for the defeat of the Han people, Bodhidharma seemed to embody values that were capable of saving the nation. On the one hand he had already become a symbol representing a synthesis of what was good and essentially “true” in Chinese culture. On the other he offered a pathway to mystical attainment that promised not just spiritual salvation, but military prowess as well.

The monks of Shaolin were faced with a similar dilemma. With the defeat of the Ming dynasty their temple could no longer depend on the imperial patronage of their martial system as a means of support. The monks would have been forced to teach what was popular in the area, and increasingly that was unarmed boxing. Shahar also speculates that the mixture of martial, philosophical and medical knowledge offered by traditions like that preserved in the Sinew Transformation Classic may have been of great interest to them.

One might also speculate on the role of market incentives in all of this. The creator of the Bodhidharma tradition had sought to appropriate and denigrate the martial prowess of Shaolin to promote his own system of internal training. In the wake of the temple’s destruction at the end of the Ming, warnings of the monk’s empty practices looked as though they had come home to roost.

In this new environment Shaolin may have been forced coopt the Classic and eventually venerate Bodhidharma as the author of their martial arts tradition, even though at least some of these individuals would have known that he was not thought of in these terms during the final years of the Ming dynasty. In short, a subset of both cultural elites and Shaolin monks likely invested themselves in the promotion of the Bodhidharma system even though they would have known (or had strong reasons to suspect) that the prefaces to the Sinew Transformation Classic (the text that started it all) were essentially works of historical fiction.

Kung Fu as a Hyper-Real Religion

There are lots of different ways in which one could interpret or make sense of the situation that I outlined above. When attempting to understand why individuals hold certain fictitious beliefs about the past one could start with functionalist explanations. Perhaps these beliefs, if they come from the grassroots levels, are examples of “folk histories,” what James C. Scott has called “weapons of the weak.”

These stories are essentially normative argument meant to re-balance prestige or power within the community. Perhaps this is a good way of thinking of the Sinew Transformation Classic’s plebian roots. Alternatively such stories might be thought of as “invented traditions” in the vein of Hobsbawm and Ranger if they instead reflect elite interests. I have explored both of these concepts in other places.

In the current essay I would like to consider another possibility, drawn from the field of religious studies. Both “invented traditions” and “folk histories” see the perpetuation and acceptance of historically dubious stories in essentially materialist and strategic (one is tempted to say Machiavellian) terms. While individuals in the distant future might come to accept an invented tradition as legitimate, the creator will always be aware of the truth. He is much more likely to be incentivized by either economic or political struggles.

Yet what if the creator of the story actually “believes” it? Or to turn the situation around, what if future generations acknowledge that the story is essentially fictional but structure their identities and norms around it anyway?

In the west we have a very strong tradition of believing that our religious communities are based on historical events. But is this really the case? Jesus of Nazareth may have been a historical individual, but he left no modern witnesses. His life story was interpreted years after his death in four gospels, each of which is strikingly different. In some fundamental ways they are simply not telling the same story. So how is it that a believer can accept each of these four accounts?

The answer appears to be “easily.” The human mind has a great capacity for synthesizing and resolving these sorts of differences. It must, because all we will ever perceive are imperfect representations of the universe. Jean Baudrillard has discussed at length how in the modern age our experience of “reality” tends to collapse beneath the weight of increasingly abstract representations of the world. Obviously certain trends in the modern media accelerate this, but it should not be thought of as an exclusively “post-modern” issue. Some areas seem to be more susceptible to the rise of hyper-reality than others.

Consider religion. How many of us can actually claim to have felt a divine presence? And how many times within our lives has this happened? The central objects of religious performance are rare indeed, but their representation in art, liturgy, myth and ritual are ubiquitous. One suspect that for most people the “representation” of the truth is all that they will ever actually experience.

Adam Possamai, a sociologist of religion, has applied these basic insights to understand a growing group of new religious movements which are founded on avowedly fictional texts. Star Wars, Harry Potter, the Matrix and the novels of J. R. R. Tolkien (to name just a few examples) have all spawned religious or spiritual movements in recent years.

The adherents of these “hyper-real religions” are not delusional. They are very much aware that Star Wars is just a movie, and that the remains of “elves” will never be found in the archaeological record. Yet in their consumption of this material they have sought to weave together underlying mythic fragments in such a way that elements of the story, or its characters, become embodiments of important social values.

The popular nature of these stories allows for the creation of new types of communities built on a shared reverence for these values. Interestingly enough the norms that these groups espouse tend not to be particularly novel. One can usually identify “old religions” that teach the same basic tenants. Yet for some reason the myths of these older social communities have become “disenchanted.” They have ceased to open a space for wonder, or even imagination, in the hearer. It seems to be at these moments that individuals strike out, and begin to look for new stories.

In this sense it doesn’t really matter whether a myth has a historical basis or not. Chronological accuracy is not what determines how a symbol functions within a faith community. Fictive power is most important.

In a chapter titled ‘“A world without rules and control, without boarders or boundaries.”: Matrixism, New Mythologies, and Symbolic Pilgrimages.’(Adam Possamai (ed.) Handbook of Hyper-real Religions. Brill. 2012) John W. Morehead has offered some guidance as to how fictional stories function in the construction of a religious community.

One of his central points is that to be effective such stories are often nested symbolic systems. There must be an element of the story that focuses on personal transformation. This is what holds out hope for individual renewal and empowerment. Yet at the same time the story must also work on a macro-social level.

The types of scripts that are adopted by hyper-real religions in the west today generally tell a very strong cosmic story as a way of addressing the larger social situation. They graphically illustrate the decay and corruption of the old system, while holding out hope that it could be transformed or remade. In essence, the new myth must explain why the previous system of finding meaning in the world has failed.

Lastly these stories tend to provide a bridge between the individual and the social/systemic level. By engaging in a course of personal transformation one furthers the process of systemic evolution or change. The story gains its psychological power by ushering its listeners onto the cosmic stage.

One does not have to be an expert in peasant uprisings or late Qing history to hear much that sounds vaguely familiar in this description. The many rebellions, tax revolts and armed insurrections that wracked northern China in the 18th and 19th centuries often coalesced around millennial outpouring of popular spirituality or new religious movements. At least some of these, most notably the Boxer Uprising, saw individuals adopting the social scripts of, and in some cases even being subjected to spirit possession by, entirely fictional characters from popular theatrical performances.

It is possible to argue that impoverished peasants may have had such a poor grasp of history that they did not known that figures like Wu Song were fictional. Still, most of them were farmers, and very familiar with farm animals. It is hard to imagine that any of them thought of “Monkey” and “Pigsy” from Journey to the West as historically real personages. Yet they were among the most popular figures employed in spirit possessions.

Historians have long debated how to deal with the various accounts of spirit possession that we see arising out of these episodes. Likewise how many of the individuals involved in “White Lotus uprisings” were really fervent believers? The logic of hyper-real religions suggests that we may be asking the wrong questions. Rather than seeing 19th Chinese peasants as exceptionally deluded when they become involved in new religious movements, we might instead take this as opportunity to reexamine some of our own assumptions about what “real” religion is, and the role that it plays in society.

Conclusion: Bodhidharma’s Never Ending Journey into the West

These same ideas have interesting implications for our understanding of the role of Bodhidharma in the modern martial arts. His story first arose and galvanized individuals behind a narrative of personal transformation at a time when the Ming dynasty was coming under stress. He exploded in popularity among more educated martial artists and readers when the basis of the old social system was disgraced and facing an existential crisis. Likewise in the modern era his memory has thrived among communities of martial artists who are looking for a remedy to the woes of post-industrial capitalism.

In each of these three eras the figure of Bodhidharma, as a fictional rather than a historic construction, has been imbued with certain key social values. In times when other avenues of social expression were becoming stale, his memory continued to open a route to personal transformation and empowerment.

Students of hyper-real religion have noted that these spiritual systems tend to generate their own types of pilgrimage. Fan conventions seem to be a way to both boost group identification and to engage in a collective reaffirmation of the central values that individuals find within the shared myth. Morehead notes that pilgrimage, as a religious journey, involves more than just geographic travel. It contains a deeply personal element.

In writing this essay I have started to wonder if perhaps martial training serves as type of “perpetual pilgrimage” for certain students. The creation myths and legendary figures of the Chinese martial arts embody values that we yearn for. In pilgrimage and ritual we engage in “rites of passage” that allow us to approach the abstract values that motivate us.

It does not take a great leap of imagination to see the process of martial arts training as a ritual of personal transformation. Students are separated from society so they can enter a liminal state. There they are deconstructed and rebuilt through both physical and psychological challenges. These come with the promise that when they renter society they will be different. And because of them the community will be different as well.

The genius of modern Asian martial arts training is that it can become an initiatory ritual that never ends. It allows the student to prolong that liminal state, to remain in contact with those core values and identities that motivate a quest for transformation.

Myths, regardless of their historicity, are a central part of this process. On a personal level they explain to the student the social meaning of their actions. They help to make sense of the many embodied experiences that go along with martial arts training.

On a broader social level they have an ability to travel through society, expanding the size and the scope of the community of practitioners. This in turn grants a sense of expertise and an increased measure of social status to those who have previously joined and started their training. The growth of the system becomes a testimony of its legitimacy.

Stories and legends, such as that of Bodhidharma, allow for the creation of new social communities where none had existed before. They open a space for individuals to cultivate and experiment with different values. Almost nowhere else in the modern world can an ordinary individual be so completely transformed, or assume the aura of a “master,” as in the Asian martial arts.

We have now come full circle. Why has the Bodhidharma legend survived more than 300 years of continual debunking? As a myth this fictional story powers the creation of social groups that have a very real impact on the lives of individual practitioners. Many of these students will be somewhat marginal. They will have entered the group precisely because the orthodox social ways of explaining the world no longer worked for them. The martial arts become a ritual that allows for the perpetual reenchantment of their lives.

Historical or academic critiques aimed at disrupting this are by definition coming from a different value system. Sometimes, as in the case of modern professional historians, this process is “entirely academic” (if not always benign). In other cases, such as the writings of Tang Hao, one suspects that his historical arguments were being marshaled as weapons in a conscious attempt to destroy the social world of the traditional martial arts so that it could be remade in a way that the Chinese state would find more useful. In either case practitioners are unlikely to accept a historical critique precisely because it is coming from a social position that they have already rejected in favor of something that they find more subjectively meaningful. In short, never underestimate the power of motivated cognitive bias to shape the world we inhabit.

The rise of the myth of Bodhidharma was one of the most important developments in the martial arts of the Late Imperial period. Not only is it still with us today, but it has spawned an entire genera of other stories (most notably the Taijiquan legend of Zhang Sanfeng) which have helped to buttress it, creating a rich and complex world view. The concept of the “hyper-real religion” might help to explain how a clearly fictional tradition has continued to be so influential for so long. The same idea might also help us to think more clearly about the relationship between fiction and popular religion in a number of other areas that relate to the Chinese martial arts.

oOo

If you enjoyed this post you might also want to read: Can Donnie Yen Bring Kung Fu (Back) to the Star Wars Universe?

oOo

March 11, 2016 at 1:01 am

Thank you for this interesting article. Hope to see an entire scholarly work focussed on this issue. As a practitioner of both Indian and Chinese martial arts I’ve noticed many similarities in martial arts styles from both the cultures which can only be happen through direct exchange. My studies into this has showed me many other possibilities of exchange. Even though historic evidences are pointing towards a fact that the Bodhidharma myth is baseless and he may have never existed, it doesn’t mean that there were no exchanges of ideas between Indian and Chinese in the past (including martial/military arts).

What I’m trying to express is that, I’ve notices that many of the “Debunking” proponents have taken a very extreme approach in Sino-Indian martial arts connections. They many be those people who are religiously affiliated to one particular martial art who just can’t take the “Mother of all martial arts” theory used by many Indian martial arts promoters in the market. For these debunkers, things are always in black and white. They say that since there are no evidences, Bodhidharma never existed or Indian influence in Chinese martial arts never happened, CMA is indigenously developed and so on.

Myths are not something which are completely irrelevant in historic study. There will be a history behind the creation of every myth and sometimes these mythological characters collectively represent unknown or nameless people who played important role in making history.

From my experience in training in both arts, I can say that there are many areas like weapon sparring forms, power generation, applied movements where similarities can be seen. And also the Chinese Qigong and Tong Zi Gong exercises have striking similarities with similar Indian arts and just because we don’t have any evidences doesn’t mean that they are not connected. Many people just come to conclusion by comparing and judging arts after watching youtube videos (which in most cases are cinematic demonstrations and doesn’t represent real arts) and comparing wrong styles among hundreds of styles practiced in both cultures.

There are numbers historic references to people from the Indian subcontinent who came to China in the form of monks, translators, merchants, sailors, mercenaries etc and is the same the other way too. Till the advent of European explorers in Indian sub continent, the major traders were the Chinese and Arabs. The Chinese had even autonomous settlements in these areas and even now there are many historic living relics of Chinese culture in Southern India. Even now some of the folk martial arts styles practiced in south India have specialised routines called Cheena Adi (Chinese boxing) in them.

So the scope of study is endless..

Anish

March 11, 2016 at 4:42 pm

Reblogged this on The Land of the Wu 巫.

May 14, 2016 at 9:51 pm

Another great article. For your interest Lee Ying-Arng wrote briefly about this some 45 years ago and I had largely re-published that for a magazine article in 1975, the text of which can be found on our website at http://www.earleswingchun.com/kungfu-history