****We recently completed the “500 Likes” challenge at the Kung Fu Tea Facebook group. As a result I let the readers vote on what two articles they would most like to see covered. There were a lot of good suggestions but no overwhelming favorites. However, a number of you wanted to see “something” related to Hung Gar. So the following essay will discuss Wong Fei Hung’s evolving role in southern Chinese popular culture.

I also noticed that there was another group of readers who wanted a post on armed escort services in the late Qing/early Republic period. If I can find some solid resources to work with, that will be the second essay that I write. This one may take some time as its a tougher subject to research. Once again, thanks for all of your support!****

Introduction: History in a World of Kung Fu Heroes

Some students have suggested that the residents of southern China are hopeless historians. This is not because they lack an interest in historical subjects. These are often featured in short stories, novels, operas, movies and television programs. Rather the issue seems to be that some individuals have no interest in separating these fictional accounts from “real history.”

This has caused much frustration for researchers attempting to uncover the origins of the traditional southern Chinese martial arts. Many popular accounts of the creation of these styles trace their roots back to the “Southern Shaolin Temple,” a institution which most historians now agree never existed (at least as it is described in 20th century legends.) It would, however, be incorrect to assume that all of this is the result of carelessness.

In fact, popular culture in southern China is very interested in the preservation of certain stories, just not in a static format. Some scholars have detected in this easy intertextuality and disregard for simple linear history a self-conscious postmodern aesthetic. This is an interesting idea and it may help to interpret the work of certain film producers.

Other writers have pointed out that there are probably more direct ways of explaining how southern Chinese audiences experienced and understood these works. Virgil Ho notes that this love of rewriting and splicing historical narratives has a long tradition (often explicitly criticized by Confucian trained cultural elites) in regional vernacular opera. In his view it was a relatively simple way for traveling companies to create new scripts, easily tailored to a specific audience, which would attract a large and excited crowd. The same tendency seems to have extended to other mediums, such as serialized novels and radio programs.

Gina Marchetti, in her 2006 paper “Martial Arts, North and South: Liu Jianliang’s Vision of Hung Gar in Shaw Brothers Films” goes somewhat further in her explanation of these anachronistic tendencies. She claims that the martial arts appear in Hong Kong films as a universally understood allegory for Chinese history. But this metaphor was not invoked out of a sense of pure nostalgia (at least not in the films that she discusses). Rather conflicts between schools or practitioners were presented “as a way of understanding a common present and a possible future.”

In short, we make a mistake when we view the portrayal of the martial arts as a backwards looking exercise, or a yearning for a simpler time when China existed in isolation from the world. Contemporary audiences love these stories precisely because they identify with the struggles of the protagonists and see in them ruminations on present and coming events.

Tony Williams has pointed out that there are a number of reasons why martial arts movies might be especially well adapted to these purposes, particularly for audiences in Hong Kong and the Chinese diaspora. In “’Western Eyes’: The Personal Odyssey of Huang Fei-Hong in ‘Once Upon in China’” Williams argues that the realities of censorship mean that pressing political and social problems needed to approached discreetly. The rich, yet historically flexible, world of Kung Fu provides a setting where arguments can be publicly stated which might not be acceptable if they were presented in a more “historically accurate” manner.

Williams argued that beyond their pure entertainment value, films such as Jet Li’s 1990s Wong Fei Hung series were part of a well understood social conversation. While the details of historical events may not have been important to audiences, they were paying close attention to the evolution of these conversations about local and national issues. Audiences were very much aware of examples of visual references, borrowing and intertextuality. This was the realm where they demanded consistency. The juxtaposition of various historical or mythic elements in new and creative ways was a tool for directors to provide that.

Simply put, it’s a mistake to look for historical accuracy in Kung Fu films. Individual directors may be more or less interested in a “realistic” treatment of their material, but this is not really what the genera is about. Rather we might better think of these stories as a continuation of Chinese opera’s embrace of abstraction.

This does not mean that we should ignore how Kung Fu films use history, or even the history of the genera itself. On the contrary, I think that both are very important subjects. The Chinese martial arts are both a specific technical practice embraced by discrete communities of like-minded students, and a potent force in Chinese popular culture. Occasionally events in the first realm will influence the latter. And it is almost always the case that media portrayals of the martial arts condition the expectations and enthusiasm of new students. This interplay between these two realm, each with its own logic, is an important area for further study.

One of our best guides in this process is Paul A. Cohen’s landmark study History in Three Keys: The Boxers as Event, Experience and Myth (Columbia UP, 1997). In this volume Cohen argues that no single approach will be sufficient to fully understand any historically complex event or process. Through an examination of the Boxer Uprising he demonstrated that the “global” reconstructions offered by modern historians often differed substantially from the lived experiences of those who participated in these events. The legends that emerged from these more specific experiences often became powerful motivating forces within Chinese society driving debate and action at different points in time. Anyone wishing to understand the actual impact of the Boxer Uprising on the evolution of Chinese popular culture needs to look at each of these elements.

One could make much the same argument with regards to the Southern Chinese martial arts. During the late 19th and early 20th century these practices, carried out by discrete groups, underwent a process of change and transformation that historians of the region are still trying to come to terms with. However, the experience of any individual martial arts teacher or school will likely not reflect the totality of this social transformation. Instead it will be a single set of experiences.

Some of these subjective understandings have been adopted by the local community as powerful myths and expressions of identity. They are discussed, watched and shared even by those who have no contact with, or any interest in, the actual physical practice of boxing. Just as Cohen argued, one cannot understand the full impact of these fighting systems on Southern Chinese society (let alone the global community) without coming to terms with each of these processes.

Wong Fei Hung: Creating a Metaphor for Southern Culture

Wong Fei Hung (1847-1924) is something of a mystery. He is possibly the single most identifiable personality in the southern Chinese martial arts. “He” has starred in more kung fu movies, TV shows, penny novels and radio dramas than any other figure. Further, his story is tightly linked to the recent history of the Pearl River Delta region (specifically Guangzhou and Foshan).

For all of this cultural importance, we have very little concrete information (of the sort that a professional historian would be willing to accept) on his actual life. We know a bit about his father, his career as a military trainer, his professional life and assorted family tragedies, and that is about it. Yet through the stories passed on by his students, grand-students, and legions of newspaper and script writers who followed, he has become the preeminent symbol of the southern Chinese martial arts.

At some point I would like to explore Wong Fei Hung’s actual life and career in greater depth. I suspect that this will have to wait until more abundant resources become available. Still, it is clear that he had his greatest impact on the Chinese martial arts after his death. As such this post asks what his story suggests about the evolution of popular culture and Chinese identity in Hong Kong.

Wong Fei Hung has been at the forefront of the entertainment industry’s engagement with the martial arts from the late 1940s onward. One source reports that over 100 films and TV shows have been produced around the exploits of Wong and his most famous disciples. With so many observations it is relatively easy to see how his character has evolved and changed with the times.

A full exploration of this topic could fill a hefty book. As a result I have decided to limit our exploration of Wong’s character to two of his most important films. The first of these is Wu Pang’s 1949 “Story of Wong Fei-Hung.” This film was the first feature length production on the exploits of its eponymous star.

The origin of Wu’s script is actually somewhat complex and it demonstrates the emergence of the Kung Fu film genera out of preexisting modes of story-telling. Much of the film is actually based around an earlier radio broadcast which had sought to dramatize the exploits of Wong Fei-Hung and his students. Such programs were common around the world in the 1930s and 1940s, so it is not surprising to see that they were adapted to the martial arts in southern China.

Of course these radio broadcasts did not emerge in a vacuum. They drew off of a large body of popular novels which recounted the exploits of various martial artists. Prior to the 1950s these stories tended to focus on local heroes from the communities of the surrounding region. Hamm has demonstrated how the influx of northern refugees following the 1949 liberation of the Mainland led to the growing popularity of an alternative school of historical dramas set against the backdrop of the northern plains.

The Wong Fei Hung narratives emerge from the earlier period of story-telling. Here the emphasis was not of national issues, but rather the expression of strong regional identities through both local custom and martial excellence. While both the novels of Jin Yong and the stories of Wong Fei Hung were very popular in Hong Kong during the 1950s and 1960s, it is potentially important to remember that these stories might not have been equally popular with all audiences, nor did they share the same basic thematic concerns.

“The Story of Wong Fei Hung” was a huge hit with working class Cantonese audiences. In fact, it was the success of this film that the subsequent franchise was built on. The movie starred Kwan Tak-hing, a veteran opera performer, as Wong. Kwan had a strong martial arts background and a large imposing frame. His presence on screen electrified audiences.

While quaint by modern standards, the martial arts in this film were meant to be as realistic and hard hitting as possible. There were no magic swords or unrealistic wire work. Even the poles, spears and butterfly swords seen throughout the production were unmistakably real weapons.

Wu interest in authenticity went beyond mere aesthetics. It should be remembered that this film was released the same year that the Republican government fell on the mainland. Looking at recent events and future trends (modernization, westernization, the influx of northern refugees) Wu was concerned that authentic southern Chinese cultural traditions and identity would be lost. His response was to attempt to preserve them where possible in his films. Apparently Hong Kong’s Cantonese speaking audiences shared his fears.

This is actually an important fact to keep in mind when watching “The Story of Wong Fei Hung.” The plot evolves episodically. The movie opens with a long scene focusing on Lion Dancing in Foshan. Wong and his school have journeyed to the smaller city from the capital to participate in the festivities. Wu, unexpectedly, does not linger on this plot point. Instead he focuses his lens on the Lion Dance team as it goes through a protracted mock battle with a crab as part of its attempt to “pluck the greens” left out by a local shop.

Following this the audience is introduced to a lecture on the history of the Hung Gar style and its relationship with Shaolin. After a confrontation with a local gangster who has kidnapped a shop owner’s wife, the action is again interrupted by a detailed performance (and discussion) of Hung Gar’s “Eight Direction Pole Form” which has no apparent connection to the rest of the story.

Wu’s film progresses in this episodic fashion from beginning to end. Whether it was traditional Lion Dancing or working class “dragon boat songs,” the director made a concerted effort to showcase vanishing elements of southern Chinese popular culture. The end result is an odd mixture ethnographic and kung fu film making.

“The Story of Wong Fei Hung” is exciting precisely because it was a creative and original project. It is not hard to imagine why Cantonese speaking audiences received it with such enthusiasm. They too felt the dual threat to their way of life posed by westernization on the one hand and the recent Communist takeover on the other. Given the important place of martial traditions in defining and creating a sense of local identity, who would not be excited to see Wong Fei Hung personally explaining and narrating the proper performance of the Eight Directional Pole Form as a top Hung Gar master demonstrated the set on the big screen?

While shot on sound stages, the film managed to include other elements of “realism.” Wong Fei Hung was a strong leader, but he was not invulnerable. At one point he was seriously injured and might have died if not for the intervention of two quick thinking women. And while Wong was shown as being nothing if not upstanding, he still could not fully control his more unruly and adventurous disciples. Of course the “troublesome disciple” is a stock figure in any good shaolin story, so perhaps we should not hold this against him.

At this point it might be instructive to take a moment to think about Kwan Tak-hing’s version of Wong. While physically imposing he is never violent. In fact, he is a master of the language of diplomacy and will attempt to solve any problem he has with his words before resorting to his fists.

Kwan’s Wong is also a leader of men in an almost exclusively male world. He is the patriarch of a large clan, and he is never without this martial arts family. This Wong Fei Hung is not a brash young hero. He is older and seasoned. He succeeds as a leader as much as he does as a fighter. For lack of a better term, this vision of Wong Fei Hung is highly political.

There is also a darker side to this. Kwan’s vision of Wong can be piercing and authoritarian. He is utterly conservative in his martial arts teaching methods and has no reservations about throwing poorly behaved students in an ersatz dungeon that he keeps in the basement of his school.

Women are also a matter of some consternation in these films. Following the lead of early martial arts novels, there are few genuinely positive portrayals of strong female characters. At best women are seen as a complication or an intrusion into the manly world of “Rivers and Lakes” in which Wong’s plays the role of Patriarch. They either make one a target of ill-intentioned villains or, by their mere existence, pose an almost existential threat to the hero’s virtue.

Kwan Tak-hing creates an unrelentingly Confucian vision of Wong Fei Hung. In fact, this portrait of a Confucian Gentleman is more at home in the late 19th century than the Republican era that most of the audience of these films came of age in. Nor does it seem to be a terribly accurate reflection of the historic Wong Fei Hung. He is known to have married a number of times and even opened some of the region’s first martial arts classes for female students.

This is a unique dilemma that seems to reoccur in our collective memories of historic martial arts masters. Very often these individuals succeeded and became more famous than their peers precisely because they were innovative in either their practice or approach to the art. Yet in our collective memory they become an anchor for “traditional” culture, meaning and identity.

Of course what constitutes “tradition” is open to almost never-ending process of renegotiation. Hung Gar is an interesting topic precisely because we can see that process happening overtime as its origin stories and major figures are reimagined and redrawn by each succeeding generation.

Once Upon a Time in China: The Adaptable Wong Fei Hung

Kwan Tak-hing vision of Wong Fei Hung defined the public memory of this master throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Over the course of dozens of films audiences watched Wong dual with his arch enemy and negotiate the treacherous waters of local rivalries and conflicts. This was a culturally conservative vision of Wong that never lost its regional focus. It stayed true to its roots in what Hamm termed “Old School Guangdong Martial Arts Fiction.”

This should not be taken as a suggestion that these films were solely backwards looking. Instead scholars might consider how they functioned as a reaction to the sudden displacement of Cantonese popular culture in Hong Kong by large number of Northern refugees in the late 1940s and 1950s. These individuals often claimed that Southern China lacked any sophistication or authentic culture. The upright Wong Fei Hung (and his many battles against unreliable neighbors) was seen by many as a convincing counterargument and demonstration of the value of southern Chinese culture. In this way Hung Gar moved beyond the practice of a relatively small group of students and became central to the very nature of regional identity.

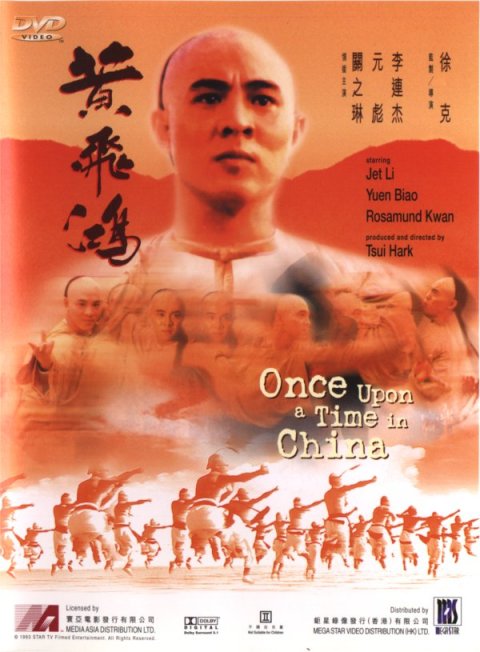

The character of Wong Fei Hung went through cycles of popularity in the 1970s and 1980s. While never forgotten, by the 1990s audiences showed themselves to be ready for a new vision of Hung Gar’s patron saint. They received this in Tsui Hark 1991 production of “Once Upon a Time in China” staring Jet Li as a younger and more active Wong Fei Hung.

It is actually interesting to sit down and watch the Wu and Tsui films back to back. There are a number of visual references that the discerning viewer might be able to pick out. Tsui knows the intellectual genealogy of his protagonist, yet he also has his own argument to make about what southern Chinese culture needs to do to survive in the current age.

Whereas geopolitical elements are entirely missing from Wu’s 1949 film, they dominate Tsui’s vision of a China under siege. Like his predecessor’s movie, this one also begins with a Lion Dance. But this time it is staged on a Chinese warship anchored in the Pearl River. As the camera is panned around it quickly becomes evident that the harbor is packed with warships, all flying various flags (American, British, French, Chinese ect..).

As Lion Dance progresses fire crackers are lit. Their explosions are misinterpreted by Western navel personal who believe they are under attack and return fire, only to kill the lead Lion Dancer. At this point Wong Fei Hung (a guest of the Admiral) springs into action to catch the head of the Lion before it falls, and to redeem the honor of the Chinese fleet (and society) by skillfully “Picking the Green.” This early tragic encounter sets the stage for the rest of the story in which Wong’s local militia repeatedly comes into conflict with callous western imperialists and the local gangs of thugs which they employ. Wong’s life is also made more difficult by neighbors who would rather ignore problems than address them and the inept local authorities who distrust all Kung Fu schools due to their supposed ties with Triads.

Interestingly Williams never comments on this last aspect of the story in an otherwise comprehensives article. Yet it is something that readers should consider. Throughout the post-WWII period Hong Kong’s government demonstrated a high degree of distrust and dislike of martial arts schools. It viewed these institutions as backwards and unproductive at best, and more often than not as a front for criminal activity. In fact the sort of harassment that Wong Fei Hung suffers at the hands of the local government in this 1991 film probably would have elicited nods of sympathy from any martial artist in the audience.

This is actually an important interpretive clue that sheds light on other areas of the film. Perhaps the easiest thing to do would be to read Tsui’s script as a move away from the parochial concerns of the 1950s towards a grander story with “nationalist” implications. The frequent and bloody massacres committed by the imperialist forces in the film would certainly seem to suggest this.

But a closer reading of this story shows that it is resistant to such a simple interpretation. Indeed, that in itself is interesting. The strong Confucian ethics embodied in Wu’s vision of Wong Fei Hung served to create very clear moral dilemmas for the viewers. There was never much doubt about who was really in the wrong in these stories, or the ability of traditional Chinese culture to handle whatever challenges might arise.

Tsui offers his viewers no such comfort. In his vision the forces of imperialism and westernization are causing a crisis, but the way forward is not clear (at least not at first). Nor does he allow members of the audience to make an easy identification between traditional Chinese culture and “good” or western culture and “evil.” True, there are some cartoonishly evil western villains in this film. But there is also Aunt Number 13 and her enthusiasm for western technology, the Christian missionary who testifies on Wong’s behalf when the rest of the town abandons him, and the Chinese-American disciple whose English skills save Wong’s life.

Even greater complexity is exhibited in the treatment of traditional Chinese culture. In 1949 Wong Fei Hung cut an unapologetically conservative figure. He was a master of traditional modes of conduct and norms of behavior and skillfully used these to avoid conflict wherever possible.

In 1991 the situation is more complex. As often as not it is the villains, rather than the righteous patriarchs, who have become the masters of traditional culture and they use it to their advantage. These modes of speech and behavior seem to cause Wong and his followers confusion. They are employed to create conflict rather than smooth it over.

Likewise Master Yim, a traveling martial artist who has come to the south to challenge the local masters in the hopes of setting up his own school, seems trapped by tradition. Williams reads him as backwards looking and resistant to change, as well as too eager to trade his martial skill for money.

I think that we can probably be a little more nuanced in our understanding of Yim’s character. Indeed, he is supposed to be a largely sympathetic (if tragic) character.

Yim’s actions are simply those expected of any traveling swordsman in the “World of River and Lakes.” His concern is not really with the foreigners at all. Rather this is the process that one is expected to go through to set up a school. It is the same process that Wong Fei Hung’s father would have gone through in the mythic world of Kung Fu stories.

The real tragedy of Master Yim was not that he sought to make a living by the martial arts, but it was that by following the prescribed social norms of the Rivers and Lakes he was forced into a confrontation with Wong rather than uniting with him to oppose foreign aggression. Whereas Wu’s 1949 film sought to enshrine and preserve local culture, Tsui’s 1991 masterpiece set out to problematize it. Wu’s protagonists are marked by their self-confidence, but Tsui’s Wong is forced to wrestle with self-doubt.

Williams argues that it is precisely this self-doubt that suggests that this film is not really about nationalist themes. As the 1990s wore on Hong Kong’s residents became increasingly ambivalent about the 1997 return to Chinese control. Hong Kong would remain tightly integrated with the global economy, yet it would increasingly be drawn into the Chinese political and cultural sphere. Once again, local identity was seen as being threatened.

Tsui’s response to this was to warn viewers against a desire to return to a simpler time. While still the leader of community, his vision of Wong’s surrenders his Confucian self-confidence precisely so that he can engage with, and eventually adopt, western tools and ideas. Only by doing so is he able to maintain both his relevance and sense of identity.

Wu’s usage of Southern Chinese culture attempted to treat it as an object. His impulse was to put it under glass so that it could be preserved. Tsui, on the other hand, sees culture and identity as a process. Wong Fei Hung’s challenge throughout this series of films (five sequels were later added to the original 1991 release) is to judiciously choose which path to follow. Williams points out that the opponents who he faces are often not so much evil as sadly mistaken in their choice of strategies for negotiating the current climate of crisis.

Conclusion: Ip Man as a Southern Chinese Culture Hero

Wong Fei Hung has proved to be one of the most popular and enduring figures in the mythology of the southern Chinese martial arts. Through dozens of novels, movies and television shows he has blazed a trail for what a local martial hero should be. Such an individual needs to provide a clear anchor to a shared past. This is necessary to unite a broad audience. At the same time they must suggest ways to negotiate Hong Kong’s ever evolving engagement with both China and the global community.

Recently a number of films have been produced that focus on the life of Ip Man. A Wing Chun master from Foshan, Ip immigrated to Hong Kong in 1949. He eventually created a successful teaching organization and trained many students, including Bruce Lee.

Lee helped to make his teacher a known figure within the Chinese martial arts community, but it was really Wilson Yip’s 2008 film “Ip Man” that made him a household name. A number of other films followed, the most notable being Wong Kar-wai’s “The Grandmaster” (2013) and Herman Yau’s “Ip Man: The Final Fight” (2013).

All of these films have been semi-biographical treatments that have mixed some historical material with healthy doses of creative storytelling. Each of these projects has also created a sensation with audiences. The popular response to Wilson Yip’s 2008 project was especially strong. That title probably defines the current public perception of Ip Man as a local and national hero. Wong Kar-wai’s film has received the most positive critical response and seems to have opened some new pathways for thinking about and producing martial arts films.

Ip Man’s rise of prominence has been remarkably swift. It is also highly reminiscent of the Wong Fei Hung’s ascension into the public consciousness during the 1940s. As such it seems reasonable to ask when Ip Man is walking on the trail that Wong created decades ago?

It is not too difficult to see Ip Man as a continuation of the same evolutionary process that I outlined above. There are even some visual and structural references in in these films which suggest as much. Consider for instance Wilson Yip’s original 2008 offering.

Following in the tradition of the Wong Fei Hung films, the first scene opens with a Lion Dance in Foshan. Our titular hero is then faced with a dual dilemma. On the one hand he is forced to deal with imperialist aggression (aided by elements of the Chinese community) while at the same time fending off a serious challenge by a desperate martial artist from northern China who seeks to make a name for himself by humiliating the local masters.

Structurally speaking, these stories are very similar. Further, both were high profile project that sought to be a “game-changer” in the Hong Kong film industry. Ip Man seems to directly follow in the tradition of Wong Fei Hung as a “modern” hero. While initially reluctant to fight, he later attempts to reform our understanding of what a martial artist is while preserving the dignity of Southern China.

Like Wong, Ip’s story is set in a time of great social change. In both cases imperialism and massacres are used to visually accentuate the existential threat facing Chinese culture. And again in both cases we have every reason to suspect that the actual threats that audiences were most concerned with were not the historical ones, but rather the pressures that they felt as they were drawn ever closer into China’s embrace.

In “ Imagining Martial Arts in Hong Kong: Understanding Local Identity through ‘Ip Man’” (Journal of Chinese Martial Studies, Issue 3) Zhao Shiqing points out the ways in which Ip Man quickly became a touchstone for local identity and resistance. Like Williams, he argued that many may be tempted to read the imperialist storyline in solely nationalist terms. And indeed it has a potent national appeal. But it also serves to frame, emphasize and reinforce Ip Man’s more immediate conflicts with those around him. These are corrupt local officials, Japanese sympathizers and a misguided visitor from the north who seek to tear down southern culture before he can even understand it.

Of course the similarities between these fictional accounts of Ip Man and Wong Fei Hung only go so far. The differences between the two figures are equally suggestive. The most obvious issue is the protagonist’s relationship with the community. Wong Fei Hung is always a leader. In every one of his films his primary identification is as the Patriarch of a martial arts clan. It is this responsibility that forces him to act, and eventually to innovate.

Ip Man represents a very different strain of Chinese society. He is the shown as the consummate loner. It is not that he is unfriendly. Indeed, in both the films and real life he liked noting better than to sit around and chat with a wide group of friends. But he also assiduously avoided any type of relationship that might lead to commitments or responsibility. He does not run a martial arts school in Wilson Yip’s film. Even in “The Final Fight,” when he actually does a run a school, he refuses to put up a sign board or to fully acknowledge his responsibilities to his students.

If Wong Fei Hung represents an evolving view of Confucian patriarchy and morality, Ip Man wants nothing to do with either. He is content to play the part of Bruce Wayne. Publically he cultivates the image of a laidback playboy while privately he obsesses about Kung Fu to the point that he risks alienating his wife and child.

The irony of course is that we do not actually know much about Wong Fei Hung’s background or beliefs, but the historic Ip Man actually received a formal Confucian education. Still, in his personal life he seems to have preferred to cultivate the air of a detached sage rather than an engaged community leader.

This has some important implications for our understanding of the recent films. Wong Fei Hung is always motivated to act for the good of the community, even if the way forward is not clear. With Ip Man the situation is more complex. It is interesting to consider his motivations prior to the various fights in the 2008 film.

He accepts the challenge from the new martial arts teacher in town only because he is badgered into it. He fights the Northern master (both at his house and at the cotton factory) to protect and avenge the honor of his friends. He ends up fighting the ten Japanese Karate students not because he is looking for an excuse to stand up to imperialism, but because he seeks to avenge the deaths of his Kung Fu brothers. In each of these cases Ip Man’s motivations to fight are based on very strong personal emotions.

He is shown as a humble and sincere person. Yet in each of the above cases he is drawn into the realm of conflict not by a rigid sense of duty, but by an authentic emotional response. It is not until his final confrontation with the Japanese officer that me makes a premeditated decision to fight, and potentially sacrifice himself, on behalf of the nation.

Clearly Ip Man’s choices have been leading him to that point. But rather than taking the stage as a fully formed legend (as Wong Fei Hung always did), Wilson Yip’s 2008 movie is essentially a tale about how Ip Man becomes a hero. And at the end of the day he still prefers the role of the “withdrawn sage,” the martial arts hermit, to that of community activist and leader.

One wonders if there is something about this image that appeals to current audiences in Hong Kong and Southern China. In both of these places traditional social structures are dissolving at an alarming pace. Social capital, defined as the expected bonds of trust and reciprocity between any two random members of the same community, has reached an all-time low. Individuals are withdrawing from all sorts of community activities. Even traditional martial arts schools are struggling to survive. Yet at the same time rates of education, wealth and social mobility are all on the rise.

I suspect that these sorts of basic social changes are critical to understanding both Ip Man’s sudden rise to prominence, and the particular way in which he has entered the public imagination. Young individuals today may have a difficult time envisioning the extended social community that Wong Fei Hung oversaw, let alone what it would be like to lead it. They may very well find the isolated, and emotionally authentic, Ip Man a more accessible role model. He provides a clear anchor to the past, while at the same time suggesting new ways of navigating the future.

In conclusion, this examination of the evolution of Wong Fei Hung, and the subsequent rise of Ip Man, suggests some interesting trends within southern Chinese popular culture. Wong has proved to be among the most resilient and adaptable characters in martial arts mythology. He has even helped to define the functions that new heroes must serve. To a large extent the popular portrayal of Ip Man seems to follow this pathway. However, certain aspects of his story point to the increased atomization and breakdown of a wide range of voluntary social structures. Still, martial arts storytelling remains a means of creating and reinforcing local identity. This has been an important aspect of southern China’s regional culture since at least the middle of the Qing dynasty.

oOo

if you enjoyed this post you might also want to read: Lives of Chinese Martial Artists (11): Mok Kwai Lan – The Mistress of Hung Gar.

oOo

April 30, 2014 at 4:20 pm

Reblogged this on wingchunarnis.

August 31, 2015 at 4:53 am

I stumbled on this article by chance – as someone who is a fan of the Jet Li’s movies, and practices both lion dance and wing chun kung fu (my dad learned at Ip Man’s school when he lived in Hong Kong), I found it very interesting!

My great-uncle was a martial arts actor, Shek Kien; he played the villain opposite Kwan Tak-hing in pretty much all of the Wong Fei Hung movies. My dad used to sometimes go and visit him on the set; Uncle Kien’s signature weapon was the three-section-staff, and Kwan Tak-hing would often end up with bruises on his ankles when he didn’t block the blows in time! Both of them were great martial artists as well as actors – Uncle Kien was a member of the Hong Kong martial arts board, along with Wong Fei Hung’s student Lam Si Wing – so their fight scenes were undoubtedly quite real, using real weapons.

I never met Uncle Kien, but I like reading about the industry and the time that he lived in. Thanks for the informative reading!

August 31, 2015 at 2:57 pm

Thanks for dropping by and sharing your family memories. They really help to make the history come alive! I am glad that you enjoyed the article.

August 31, 2015 at 4:54 am

I stumbled on this article by chance – as someone who is a fan of the Jet Li’s movies, and practices both lion dance and wing chun kung fu (my dad learned at Ip Man’s school when he lived in Hong Kong), I found it very interesting!

My great-uncle was a martial arts actor, Shek Kien; he played the villain opposite Kwan Tak-hing in pretty much all of the Wong Fei Hung movies. My dad used to sometimes go and visit him on the set; Uncle Kien’s signature weapon was the three-section-staff, and Kwan Tak-hing would often end up with bruises on his ankles when he didn’t block the blows in time! Both of them were great martial artists as well as actors – Uncle Kien was a member of the Hong Kong martial arts board, along with Wong Fei Hung’s student Lam Si Wing – so their fight scenes were undoubtedly quite real, using real weapons.

I never met Uncle Kien, but I like reading about the industry and the time that he lived in. Thanks for the informative reading!

May 17, 2020 at 4:27 pm

There are a few things which i like to add to your most well studied essay,

Although you convieniently left out merits of hung ga, wong fei hung, wing chun and ip man. Haha

Here is what id like to say

Whether hunga and wing chun did actually originate from shaolin i do not know but one thing is certain, they both have the same interpretation of body dynamics although hung ga focusses on different aspects and wing chun on different aspects. And if i am any authority(full disclosure i have studied martial art but i have no accomplishments to my name) both these systems are some of the very best not only in china but also in the world. And having said that both are fully realistic and combat worthy systems(i am saying that from experience).But there is a slight disparity between hung ga and wing chun where wing chun blocks are slightly superior, hung gas motion, structure and attack are superior. Ip man is credited with organising the teachings of wing chun and wong fei hung is credited with not only organising but developing the style and bringing it to its current and highly developed form(this is in all probability a historic fact as all of the current students in his lineage agree on this point and also you can contrast wongs hung ga and other families of the system.)

So which would win in a fight? Most definitely hung ga, because there is nothing in wing chun that is absent in hung ga(atleast in the ip man lineage because some branches of wing chun still show remarkable similarity to hung ga) and the converse is not true(although wing chuns teaching of blocks is more organised and condensed).

I know i havent done a good job of writing this analysis forgive me, i am not a persom of literature.