***Update***

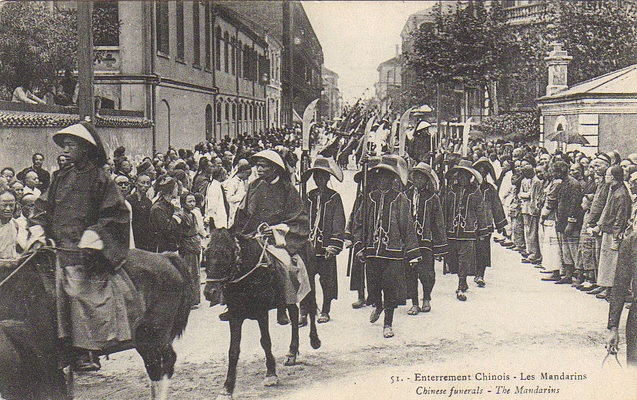

(I recently found another old photograph that goes very well with this post. It shows an official riding a horse as part of procession in pre-1911 Shanghai. I have added it below with some additional comment.)

Introduction: Romanticizing and Reviling the Martial Arts in 19th and 20th Century China

The traditional fighting arts occupied an ambiguous place in traditional Chinese society. One the one hand martial operas, stories and novels have long been popular. Actors, authors and puppeteers all profited from the public’s seemingly insatiable apatite for martial entertainment. Many period sources sneeringly note the ubiquity of marketplace demonstrations where traveling patent-medicine salesmen would use Kung Fu techniques or feats of hard qigong to hawk their wares to an unsuspecting public. Of course these sales tactics were common precisely because they were fairly effective. They played to a pervasive fascination with the martial arts.

While the idea of the martial arts may have been popular, actual practitioners of China’s various hand combat traditions were not. It would not be going to far to say that these individuals were actually reviled by the better parts of local society. While the medicine-sellers could put on a good show, most of them were also transient vagabonds in a culture that valued a strong attachment to place more than just about anything else.

Nor were most other martial artists much better. Yes, an occasional medical doctor or local landlord dabbled in hand combat. But most martial artists were either bandits, or members of local militias dedicated to keeping the bandits at bay. Neither line of work was particularly rewarding or lucrative.

Since Confucian culture assigned greater value to those who derived their livelihood from their education, minds and service to the community, martial artists (who instead employed their body for a living) were relegated to a very low position in the social hierarchy. Even groups who were expected to know and use the martial arts as part of their duly appointed social roles, such as professional soldiers or opera singers, had a social status no better (and in some cases even lower) than prostitutes.

Still, one suspect that more than ideology was at play here. Most people distrusted the martial arts because their biggest proponents seemed to be bandits and secret society members. Further, even those elements of the establishment who trained in and used the martial arts were very problematic.

The average person interacted with the government only at the most local level. This was where they paid their taxes, were recruited for work projects or perhaps became involved in a trial or lawsuit. All of these basic functions were either carried out or assisted by a class of local enforcers and toughs who were nominally under the control of the local government. This social class included both clerks and runners from the local Yamen, various types of law enforcement officers and bounty hunters, court officers, jailer and even executioners.

All of these individuals might have to employ the martial arts in the course of their jobs. Unfortunately they were also notoriously corrupt, something that became evident whenever they set out to collect taxes. And even at the best of times Qing justice was swift and harsh. It was something that respectable people tried to avoid.

While the rumors of bandits and the corruption of local secret societies probably did not help the reputation of the the traditional fighting arts, I suspect that it was actually the much more visible (and often stunningly corrupt) actions of local government functionaries that really soured most people to the entire martial realm. Today in the west one might assume that being a court secretary or a local police officer would be a high status job, because for us it is. Yet in traditional China few peasants would want to see a son entering such a profession. It would be seen as a step down the social ladder.

In the fictional world created by late Qing martial romances, hand combat was a tool to expose injustice and to right wrongs. In real life its use was usually a harsh reminder of the perpetual structural inequalities that the sate was built on. In the hands of corrupt and inept local officials the martial arts destroyed but they did not build. And that was before the bandits showed up.

It took a major public education campaign, backed by the national government and the Central Guoshu Institute in the 1930s, to really begin to displace these negative associations. The Kung Fu Craze of the 1980s and 1990s also helped to build a new, more positive set of mental associations. Even so, it is still not uncommon to encounter these more traditional and hostile attitudes towards the martial arts in China today. This is often confusing for westerns as it was the Japanese who first introduced us to the martial arts. Needless to say, traditional fighting methods play a very different role in their society. In Japan hand combat training was a privilege of the social elite and it still carries that cache today. The situation in China is much more complex and has changed a number of times in the last 150 years.

Court Officers during the Qing Dynasty

The first picture (at the very top of this post) captures the somewhat ambiguous place of these low level enforcers and assistants. Magistrates and other officials were actually required to travel with a retinue. These individuals were usually clerks and runners. Many of them may have been trained in the martial arts. Occasionally better trained guards or professional martial artists might also be added to the mix to “stiffen the ranks.”

State regulations dictated the size and composition of the retinue allowed to different levels of officials. Generally speaking the larger the entourage the more prestigious the the VIP. However, local officers were usually required to outfit their own followers. This even included buying them weapons.

Problems arose when officials attempted to economize on their expenses. Buying high quality newly forged blades could be expensive. As a result it was not uncommon for guards and runners to be armed with totally non-functioning cast iron weapons. While useless in a fight, such implements were cheap to buy. An American consular with an interest in collecting noticed an acceleration of this trend while he as stationed in China in the early 1890s:

A common weapon is a trident, tined and barbed exactly as those employed by fishermen in spearing eels. Similar to this is a three-prong hay fork. Of equally bucolic origin is a long pole to whose end is fastened the end of a scythe or sickle. The European mace is suggested by a long handled, light-headed hammer similar to that with which Charles Martel is said to have won his quaint name. It is obvious that these weapons were of harmless origin. The first was the favorite instrument of fishermen and the second, third and fourth of agricultural people.

Of the five types described here there are no fewer varieties. The poles are bamboo or solid wood. They are plain, carved, or decorated with mother of pearl, metal or cord. The heads are copper, brass, iron, pewter, or steel. Sometimes they are silvered, sometimes bronzed, lacquered or gilt. Handsome ones are the exception and not the rule. The average retainer of a high official carries an arm whose pole is of the commonest wood stained red and whose head is of the poorest kind of cast iron or impure pewter. Many of these ominous-looking implements of war would not stand a light blow, both head and pole breaking at a very slight shock.

Edward Bedlow. Consular Reports on Commerce, Manufacturing, Ect. No. 147. December, 1892. US Congress: Washington DC.

This is a fascinating report. Not all Chinese weapons of the period were of poor quality. Bedloe goes on to describe some real treasures later in the article. If you are interested in collecting Chinese swords his accounts of the antique markets of the late 19th century are mandatory reading. Yet as he makes clear, local officials were not in the habit of buying the best for their followers.

The symbolic and non-functional nature of the polearms in the preceding photograph beautifully illustrate Bedloe’s observation. The fact that these officials did not even bother to provide their own retinue with real weapons would seem to indicate that not even their employers valued their martial skills all that highly.

Of course there are two very real weapons in this photograph. The first appears to be a double rifle, and the second is the sword held by the official at the far left of the photograph. Ironically that is not a standard issue Qing military saber. Rather its a type of large sword that became popular with martial artists late in the 19th and early 20th century. Processions armed like the one above would have been a common sight in the closing years of the Qing dynasty.

Our second photograph shows a traditional court in session. This image was published by the Keystone View Company in the first few years of the 20th century. It purports to be a trial of “Boxers.” Of course the Boxer Uprising ended in 1901 and any photo that referenced those events, even tangentially, was sure to be a good seller. The reality of photography at the time would suggest that this image was likely staged, though the participants look real enough.

I like this image as it represents the workings of a local Yamen quite well. The magistrate can be seen in the middle of the photo questioning two individuals. The bound person is clearly a suspect where as the better dressed man who is not bound may be a witness. On either side of the Magistrate are two clerks who assist with the trial and record keeping. Behind them are four individuals, armed with much more functional looking Tiger Forks who would have functioned like baliffs in a western court. These same individuals would likely have also assisted the local government in other tasks, such as tax collection.

Court officers were also required to carry out less pleasant assignments. Compelled testimony and torture were a common part of the Chinese justice system in this period of time. The next photograph shows a court officer beating a man with a stick roughly the size of a cricket bat while he is restrained by two other bailiffs. A clerk or runner from the Yamen looks on. The cangue (wooden collar) on the ground would seems to indicate that he has been sentenced and is being punished for some crime. If you were a working martial artists and were employed by the local government, this was very likely how you would spend a lot of your time.

Martial artist were also employed as jailers. Their duties might include guarding prisoners who were awaiting execution or escorting convicts into exile. Exile was actually a fairly common punishment. Anyone who has read Water Margin will no doubt recall that such journeys could be dangerous. In fact, there seems to be some crossover with armed escort companies here. They also were major employers of martial artists and often conveyed both people and goods at the behest of local government officials. Further, jailers might legally accept cash payments in lieu of certain punishment, or they might illegally request bribes from either convicts or their families in exchange for favorable treatment.

Conclusion: The Martial Arts as a Tool of State Sanctioned Violence and Public Intimidation

Lastly, as the vintage postcard above demonstrates, employees of the local Yamen also carried out public executions on the orders of the magistrate or governor. These events were often fairly gruesome displays in which beheaded, strangled or finely sliced corpses might be left in a market or other public space in an attempt to “educate” and “edify” the public. Heads were also commonly displayed in cages or tied to posts by their queue. One does not need to be a political theorists to see these displays as a calculated act of public intimidation.

This brings us back to the initial point of the post. Some of the most visible martial artist in any community would have been the clerks, runners and guards who worked for the Yamen and other public officers (such as the Salt Inspectors Office). They were expected to employ their specialized skills not just in the apprehension of criminals, but also in their punishment and execution. These state rituals were designed to both horrify and intimidate the local population. When you add to this the problem of pervasive local corruption, its not hard to see how most respectable members of society would have had very mixed feelings about the martial arts and the individuals who made their living by practicing them.

Leave a comment