Introduction

The “Book Club” is a semi-regular series of posts where we collectively read and review some of the most important works in the field of Chinese martial studies. My intent is to reproduce the same sort of seminar atmosphere that you might get if you were encountering these works in a university setting as an advanced undergraduate student. No previous background or special language skills are necessary. Just get a copy of the book, read along, and feel free to ask questions. The first part of our review of Lorge (where we examine his discussion of China’s ancient Bronze Age military tradition) can be found here.

In the current post we review the chapters covering the medieval period (Song-Ming). This is the heart of Lorge’s argument. Here we see the strengths and weaknesses of the methodological and editorial choices discussed in the “Introduction” fully played out. We will be looking at these chapters in some detail, so this will be a “long read.” Consider yourself warned. However, by the end of this post we will know a lot more about Lorge’s intended audience, and where he sees the roots (or ultimate origins) of the modern Chinese martial arts.

Song Dynasty and the Diversification of the Martial Arts.

Chapter six represents a threshold within Lorge’s work. On one side of it, in the first five chapters, our author is forced to cover vast expanses of time. He spends a hundred pages working his way up from the Neolithic to the end of the Tang. One would suspect that military traditions and weapons changed immensely over this period. And they did. So how was Lorge able to cover all of this ground in only 100 pages?

As a historian (rather than say, an archeologist) he relies quite heavily on the written word. And to be totally honest, once you get back into ancient Chinese history, not that many words survive. So if you are a fan of Chinese military history you probably did not hear a lot that was shocking or new in the first half of Lorge’s book. It is not that he was holding anything back. Rather, we just don’t have a huge amount of information from the very ancient past, and what we do have is already available is any decent textbook on Chinese history.

In chapter six we suddenly find ourselves in a different world. Clouds part and vast vistas open up that just are not visible when you are talking about the Shang, the Zhou or even the Han dynasties. Suddenly we have a much richer historical record to draw on. In fact, this record is so deep that it no longer focuses only on the lives of a handful of elites. It actually starts to discuss popular culture, both in the countryside and in the new urban markets that dominated so much of life during the Song dynasty.

When examining this richer portrait of life, we are immediately struck by the massive diversification of the martial arts that Lorge describes. In ancient (Bronze Age) China the martial arts were seen in a few different realms. They were present on the battle field, there were courtly martial rituals (either archery or sword dancing), and wrestling and boxing were both promoted as a form of entertainment. Yet for the most part, actual fighting and warfare seem to have dominated most people’s experience of the martial arts.

During the Song dynasty it is no longer possible to speculate about how “most people” experienced the martial arts. We are discussing an increasingly fragmented phenomenon. Obviously soldiers still cultivated the technologies of violence, much as they had always done. Yet there are records of many new types of civilians participating in martial culture as well.

To understand how they interacted with the martial arts we need to think about three sets of variables. First is the issue of social and educational class. We need to understand how the elite experience of martial values was increasingly different from most of society. Secondly, we must start to think about urbanization. The growth of new forms of vibrant urban culture means that we must consider how those in urban areas experienced the arts differently from rural villagers or peasants. Lastly there is the question of geography. Obviously this is especially pressing during the weak Song dynasty. What did martial traditions look like in the North versus the South? How about coastal areas (the home waters of pirates) versus mountainous regions (typically dominated by bandits)? Lorge systematically addresses each one of these questions and it is absolutely critical to understand what his answers are and where they came from.

To begin with, the elite became increasingly detached from any involvement with martial practices during this period. In previous eras it seemed as though a specialization started to occur where the descendants of Northern tribesmen became a distinct military caste, and Han administrators increasingly defined their identity and function in terms of pure Confucian service understood in opposition to the martial virtues of these “northern aliens.” That is an oversimplification of a complex and fluid process, but there is some truth to it.

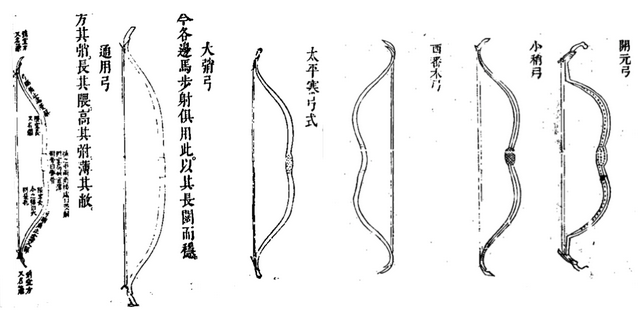

The Song dynasty was the first government dominated exclusively by the Han for centuries, and the attitudes of the ruling Confucian scholars accelerated what had been a long evolving trend away from involvement in military matters. Most gentlemen and court officials even gave up the pursuit of archery, the one martial practice that was officially sanctioned in the Confucian canon. Now even the bow was seen as being too “common” and tainted with militarism.

Most other people during this time period did have the same luxury. For them martial attainment remained a matter of survival. The Song state was institutionally weak which meant that it had a hard time effecting society on the local level. In practical terms this meant the state was unable to police their borders, fend of invaders, hunt down bandits or keep the water ways clear of pirates. In fact, all of these became major issues as the era wore on. If local landlords or officials wished to protect their towns from marauding bandits, or their trade from pirates, they were forced to train and equip their own paramilitary groups.

Various localities, clans and estates established militias and “staff societies” to deal with local problems. In the north the court even supported the creation of “archery societies” that could be used to guard against horse mounted invaders. The court loved the idea of citizen-soldiers in theory as it implied that these individuals did not have to be paid.

In practice this program was not very effective. These units lacked professional officers, were not easily integrated into the imperial military and tended to be trained for specialized jobs like hunting bandits in the hills, or fighting pirates in the bays. It turned out that defending the nation against an invasion actually had very little in common with these more specialized tasks. Plus, once you drafted the local archery or staff society, there was no longer any force to keep the bandits in check. They were then free to start taking over large sections of the countryside, which is exactly what they did.

This discussion of local militias and their role in civil society is very important. It suggests a number of similar situations that will reoccur in the later chapters of this book. The government’s response to banditry during the Song dynasty is also fascinating and prefigures later Ming and Qing policies. Petty bandits were usually ignored by the imperial government, and the local people were left to fend for themselves. If the bandits became particularly destructive or rebellious, only then would the government become involved, but usually their first response was actually to attempt to hire the bandits and integrate them into the military. After all, these individuals had already demonstrated a mastery of all of the skills necessary to be a soldier.

In previous eras fairs and markets had been highly regulated and restricted. One of the side-effects of these mercantilist economic policies was to alter and restrict the sorts of urban development that could happen. For a number of complex reasons, this system of economic management was allowed to break down in the Song dynasty. Permanent markets began to spring up and they became major centers for trade, urbanization and the growth of an expanded class of wealthy merchants and crafts people.

These markets also became critical to the development of the martial arts. Again, this should not come as much of a surprise. To be a professional martial artist someone must be willing to pay you for your skills, and there are only so many ways that this can happen. Either you work for the army, you work for a local strongman (either a landlord or a gangster), or you find a market and sell your skills as an entertainer/teacher/healer. There just aren’t that many options and the growth of economic markets are critical to all of them.

Lorge notes that there was an explosion of martial arts activity in the marketplaces of urban Song dynasty China. Most of this energy seems to have been directed into using the martial arts as a form of entertainment for the newly enriched merchant class and other urban dwellers. Of course the heady mix of drinking, gambling and prostitution that could be found in these areas would also require a slightly different, if still related, martial skill-set. Private martial arts societies (some with political overtones) and traveling groups of performers, displaying the rarely seen fighting arts of distant regions, are noted in the histories of these commercial districts.

Many of Lorge’s observations on this period are supported by the previous research of a Chinese historian named Lin Boyuan (see Zhongguo Wushushi. Taibei: Wuzhou Cubanshe. 1996). Boyuan makes the argument that it was in the entertainment quarters of the Song dynasty that the traditional martial arts went from being simple, direct, linear fighting forms to more evolved (one is tempted say “flowery”) displays of acrobatic and martial prowess. Much of the audience was already familiar with the practical martial arts and it would have taken something extra to impress them. The existence of permanent urban markets also allowed for an expansion of the class of professional civilian martial arts performers and instructors.

Specialization in presentation and display became necessary for these groups. They would teach their approach to fencing, or spear dances, to their students. By necessity it had to be impressive and substantially different from what the performance troop down the street was doing. In Boyuan’s opinion, this is where we first see the emergence of “lineage”, or the socio-familial aspect that transcends martial function, in the traditional fighting arts. Note that he is not claiming that any particular modern lineage dates back to this period. Rather it is the very idea that lineages should exist at all which seems to be rooted in the urban markets of the Song era.

This is an intriguing theory and it deserves some consideration. I have used Lin Boyuan’s research in my own writing on the 19th century, and I am inclined to pay very close attention him. He is one of the more insightful authors in the Chinese language literature.

There is an undeniable link between the traditional Chinese martial arts and economic marketplaces. You literally cannot have the first without the second. A martial arts school (or tradition of instruction) is a way for money to change hands within a social group. That in turn presupposes that something called “money” exists and that it can be obtained from somewhere. Obviously markets and monetized trade are very helpful in making all of this possible.

Note that this is not necessarily the case for a militia. Militia members generally do not get paid for defending their own homes or fields. They learn military skills on a part-time basis and these skills are not passed on in “lineages.” A martial arts society is not, culturally speaking, the same thing as a military unit, and no one would mistake one for the other. Freely operating markets in a civil space seem to make the critical difference. A lot of Boyuan’s writing and thinking seems to focus on the role of markets and urbanization on the development of martial culture.

Still, this creation of the idea of “lineages” seems to have taken a while to come to maturity. None of the heroes of Water Margin come from a “traditional,” lineage based, martial arts schools. Well into the Ming period it seems that most martial artists did not identify themselves primarily in terms of their lineage. They may have shown reverence to a teacher, but that is a slightly different issue. It is not until the end of the Ming that most martial arts schools even acquire “names.” I need to back this up with more research, but my current reading of the situation is that it is not until the late Qing dynasty that having a “lineage” becomes an absolute expectation or requirement for practically all popular boxing schools and societies.

Opera had a huge impact on the popular martial arts during the late 19th and early 20th century. During this era many unemployed opera singers simply became martial arts teacher, and most street performing martial artists seem to have known at least a little opera.

Scott P. Phillips has examined the history of opera and public performance in great detail. He notes that “lineage” has always been a major concern for singers and performers in China. In fact, during much of the Qing dynasty opera singers took the idea of lineage more seriously than did many “operational” martial artists. He has postulated that it was the massive influx of opera performers into the ranks of martial artists during the late 19th and early 20th century that helped to make a reverence for lineage the norm that we still enjoy today.

I think it is very interesting that looking at two different eras of history, both Lin Boyuan and Scott Phillips come to basically the same conclusion about the role of public entertainment and the emergence of “lineage.” The early interactions between entertainers and martial artists seems to have laid the foundations for the emphasis of this concept within hand combat schools, and the later cross pollination of the two traditions possibly contributed to the spread of the norm in the modern era. Theater has never been my specialty, so I am hesitant to make any pronouncement on this issue, but the connections seem well worth pursuing.

In conclusion, the diversification of the martial arts allows for a much more interesting discussion to emerge in chapter six. Still, I would have liked to see Lorge more directly address the question of why it emerged when it did and whether it was really new.

On the one hand, the diversification that we see here might be a mirage. It could simply be that the historical records of the preceding eras are so sparse that they present a distorted view of the past. On the other hand, genuinely new trends did emerge in Chinese society, economy and urbanization during the Song dynasty. This suggests that some of what we are seeing in this chapter could be genuinely new. I think that Lorge might have been able to add a bit of perspective both to this chapter and the preceding ones by addressing this question.

Yuan Dynasty: An Underdeveloped Interlude.

Compared with the treatment of the Song dynasty, Lorge’s discussion of the Yuan era was brief and left many questions unaddressed. Of course the Yuan Dynasty itself was quite short, lasting only a century. So on some level there simply isn’t as much to say about the time period.

Yet there were also important changes and developments during this period. For instance, the basic stories of the Water Margin were probably first composed during the Song dynasty, but we currently believe that these stories became popular subjects for popular performance during the Yuan. Given how central this myth-cycle is to the development of later Chinese martial culture, this might have been a good time to address it in greater detail. Instead, much of that conversation falls in the already overcrowded chapter on the Ming.

The Yuan era saw a relatively sharp segregation between the martial skills of the northern Mongol invaders and the ethnically Han Chinese citizens. In previous eras (such as the Tang) there had been a combining of the martial cultures of the northern horsemen and the much larger Chinese culture. No such intermingling had a chance to develop during the 1300s.

Society as a whole was increasingly segregated and classified to assist in administration. Firm distinctions were made between Mongols, other northern tribesmen, northern Chinese citizens and the occupants of southern China (generally the least respected and most distrusted group due to their long resistance to Mongol rule). This same stratification was reflected in military participation and the martial traditions allowed (or tolerated) in each group.

Mongol warriors were by tradition and ethnicity expected to serve as horse archers. Further, the basic skills of horsemanship and archery were usually mastered in childhood, long before a warrior entered military service. For this group military drill consisted of riding and tactical exercises on horseback. Yet Lorge has little else to say about Mongol training. He does provide a very interesting discussion of the ways in which archery was used as part of both martial and shamanistic rituals by the northern tribesmen at this point in time.

Other groups (especially the Han) were expressly forbidden from owning weapons or practicing the martial arts. Manufacturing or owning weapons could be a capital offense and frequent edicts were issued reminding the population of that fact. Still, it is not always clear how seriously these rules were enforced or what effect they actually had on Han military culture.

Lorge himself makes a couple of contradictory statements on the matter. While the government was free to make any pronouncement it wanted, it still lacked any sort of ability to actually protect individuals from bandits or marauders. As such local villages, temples and landed estates continued to maintain standing military forces, armed with all of the weapons one could hope for, official prohibitions notwithstanding.

The Yuan dynasty was also dependent on other groups in society to provide basic military skills and manpower. The Mongols only fought on horseback, they had no other military function or skillset. Infantry, combat engineers, and naval forces all had to be recruited from the local Han (and Korean) populations. Nor did the new government ever establish a reliable system for training people in these skills. Instead sailors, fighters and builders who already possessed valuable skills were drafted directly into the military. Of course this would undermine the government’s incentive to actually pacify and disarm the civilian population. To do so would undermine their own military strength and future ability to raise an army.

Clearly the government policy of disarmament was poorly enforced and only followed on an ad hoc basis. Certain things were much more troubling to Mongol elites than others. Revolutionary political organizations were their main concern. Estates in the more familiar, and longer controlled, northern regions of China were allowed to maintain large standing military forces with little oversight as long as they were deemed to be “loyal.”

The residents of southern China were less trusted and more restricted. The Mongols also apparently were more concerned with the ownership of bows (which they viewed as a “real” weapon) than spears or poles (which were the dominant infantry arms of the south). Wrestling and boxing skills were viewed as having no practical military application and apparently didn’t warrant much oversight or suppression. So while some arts (such as civilian archery) actually suffered under Mongol rule, others, such as pole fighting and wrestling, were basically ignored or even officially promoted as safe forms of popular entertainment.

Again, there is not much in this discussion that will surprise military historians, but Lorge does provide some nuance that is often missing in discussions about the Yuan dynasty among popular martial artists.

The Yuan is also interesting as there continued to be accounts of independent martial arts instructors traveling the countryside teaching wrestling, pole fighting and the spear. Boxing is also occasionally mentioned, but at the time it appears to have been much less common than wrestling. These teachers acquired students and moved freely. At least some merchants (who needed protection on the road) started to study wrestling during this period as a form of self-defense.

These are some of the oldest accounts of individuals in China taking up unarmed fighting as a form of protection, so a more detailed discussion of these passages would have been nice. It would have been all the more helpful as a lot of the groundwork for the interesting developments of the Ming dynasty are really coming out of things that were starting to happen in the Yuan and Song eras.

The chapter closes with a brief discussion of Li Quan and his rise to power as a bandit and regional strongman in Shandong. This is an interesting case study and it even included a note about the military use of the double swords in battle which I found interesting. But I would have liked to have seen more.

Specifically, the Yuan dynasty dissolved due to a mixture of political infighting among elites and an inability to deal with the eruption of popular rebellions around the countryside. Some of these rebellions were linked to local strongmen, others drew inspiration from millennial Buddhist cults that became popular throughout the country. These religious uprisings played an important role in bringing down the government, so it is interesting that Lorge refuses to mention or address them.

Given that the shamanistic use of archery to produce rain was discussed at some length in this chapter, one might think that the connections between new religious movements, popular martial training and anti-government revolts might spark some interest in a book that is ostensibly about the history of popular martial arts? It seems clear that Lorge’s theoretical approach to the question of religion and its involvement with violence (outlined in the introduction) has seriously hampered his ability to discuss the end to the Yuan dynasty.

I am somewhat sympathetic to his concerns. It is important to avoid reinforcing popular stereotypes of the supposed deep mystical connections between Chinese religion and the martial arts. Many, probably most, individuals who made a living from the martial arts were not what we in the west would regard as “conventionally religious.” And it is clear that the religious beliefs of individuals at the end of the Yuan did not lead to any sort of restraint on the battle field (a point that Lorge does make).

Still, monastic violence was a real, socially important, phenomenon across Asia and it must be addressed. Popular uprisings inspired or sparked by new religious movements are a reoccurring issue in both Chinese and Japanese military history. So how did the unique pattern of military evolution outlined in the rest of the chapter effect the development and efficiency of the Red Turban Rebels? That is a really interesting question, and I expected to see it addressed.

Perhaps we lack the proper theoretical models to tackle these sorts of topics in the current Chinese martial studies literature. Students of medieval Japanese military history seem to be more aware of the connections between both formal and popular religious orders and violence, and have developed rather sophisticated ways of discussing them that would avoid most of the pitfalls that Lorge seems to foresee. I personally think an approach similar to that used by Mikael Adolphoson in Teeth and Claws of the Buddha: Monastic Warriors and Sohei in Japanese History (University of Hawaii Press, 2007) or Carol Tsang in War and Faith: Ikko Ikki in Late Muromachi Japan (Harvard University Press, 2007) could have been very helpful.

While it is clear that there is usually nothing especially “religious” about the ways that these groups fight, it is also evident that we do ourselves no favors by ignoring their existence. For better or worse, temples and popular religious movements have often been important players in the social, economic and military landscapes. Of course Lorge himself cites Adolphoson’s work when dealing with the military legacy of Shaolin in the following chapter, so it is clear that he is aware of this work. Yet it is sad that he did not actually follow his lead and provide a similar discussion of monastic violence throughout the earlier chapters of his book.

The Ming: Chinese Boxing Steps from the Shadows.

The Ming dynasty was a marked contrast from the Yuan. While the state’s ability to influence all levels of society remained weak, the Ming government was much longer lived and had a greater impact on Chinese culture. It also represented a return to Han rule. Students of the traditional Chinese martial arts have a habit of venerating the Ming state because it is so often held up as a “golden age” in comparison to the later Qing. This popular view has many flaws. The basic institutions of government were seriously compromised almost from their inception, and life during the period was carried on under the shadow of brooding violence. Lorge goes some way towards restoring a more balanced view of this era.

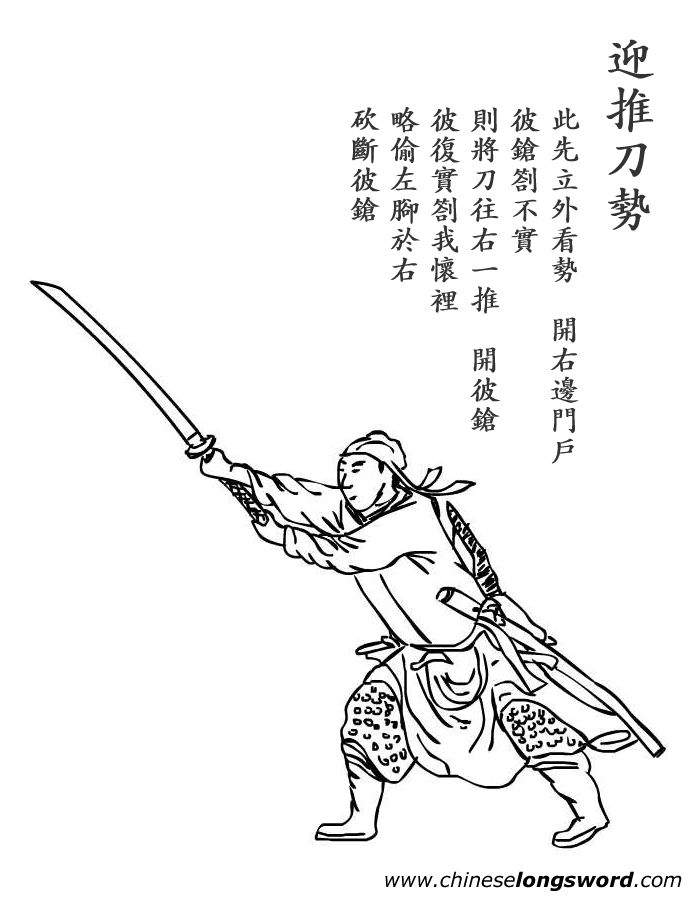

Unfortunately this chapter suffers from many of the same weaknesses that plagued the previous one. The Ming is the first era in Chinese history where we have an actual abundance of surviving military and martial texts. It is the era when many great martial arts novels were first published. It is an era where we finally possess a number of reliable accounts of the role of martial training in local society. Lastly, it is the era when unarmed boxing, both for self-defense and self-cultivation, came into its own and took on many of the characteristics that we now associate with the modern Chinese martial arts. Each one of these points deserved an extensive and careful discussion, but the chapter was very brief and felt almost cursory.

A quick look at the sources listed in the footnote will indicate why. With the exception of some offhanded comments about General Ji Qigong and Yu Dayou, Lorge never actually examined or discussed any of the existing documents from this era. His discussion of spear-fighting could have been augmented with the period accounts and opinions of Wushu. Likewise, his discussion of the role of pole and spear fighting could have drawn much more extensively on the writings of Cheng Zongyou and Yu Dayou.

To be totally honest, by the end of this chapter I was more surprised by what had been excluded from the conversation than anything that I actually read. The entire discussion of unarmed boxing in the Ming era (a subject that is absolutely critical to the history of the Chinese martial arts) was covered in less than two pages. The entire chapter consisted on a brief summary of eight secondary sources. With the exception of Lorge’s ongoing grudge against Shahar, he does not even appear to have engage most these very deeply.

Still, important facts are brought up throughout the chapter. Lorge notes for instance that the late Ming is the first time that specific schools of boxing and wrestling seem to have acquired names. While these things existed in the Song dynasty (and likely in the Yuan), they lacked the labels that modern martial artists have come to expect. How this change happened, or its broader significance, was left largely unexplored.

Lorge cites some very interesting research by Kathleen Ryor (“Wen and Wu in Elite Culture Practices During the Later Ming.” In Nicola Di Cosmo ed. Military Culture in Imperial China Harvard UP 2004) about elite long sword (jian) collecting and practice in the Ming dynasty. Yet he never really manages to connect the dots between elite participation and popular practices. How did these two groups affect each other, and what impact did a sudden influx of elite participation in the martial arts have on its practice and development? That question alone could be the subject of a fairly lengthy study.

How should we interpret this? Lorge is clearly capable of doing detailed historical research. Perhaps we should reconsider the question of his intended audience. If he was writing this chapter to correct misconceptions about the Ming dynasty that are commonly held by practicing martial artists with little background in Chinese history, then this chapter does the job quickly and efficiently. It provides a basic road-map of understanding and gives readers a half dozen other things that they could go and read.

Still, the overall feel of this chapter seems to contrast with the much more interesting discussion that he advanced when dealing with the Song dynasty. We have many fewer surviving texts from the Song, but Lorge generally did a better job of squeezing as much understanding as he could out of these facts.

I cannot help but feel that the Ming dynasty must bore Lorge. At multiple points he mentions that developments that can be clearly seen in the Ming are really just extensions of trends that started in Song dynasty. To a certain extent that appears to be true. Yet given the lack of resources for earlier time periods (compared to the relative abundance of the Ming) I wonder how far one can really go in making this argument? Still, I think that he intends for his audience to see the development of the martial arts in this period as basically a continuation of the course that was charted in the Song.

I suspect that this is why he did not go back and revisit many of the same topics that he had previously covered in greater detail during the Song. If this is the case, I would have much preferred that Lorge make his argument explicit, and go to greater lengths to show how exactly late Ming developments were connected to trends that had been noted hundreds of years before. Adding some sort of argument or theoretical apparatus to this chapter would have made this work much more useful to the academic community, and it probably could have been done without losing too many popular readers. Still, by this point in the manuscript it is clear that novice readers are his intended audience.

Conclusion: Lorge on the Song, Yuan and Ming period.

The last three chapter of this book have provided a more detailed discussion of the development and practice of the martial arts than anything which we had previously seen in the first half of the volume. In large part this has to do with the greater number of existing sources. But evolving trends in urbanization (and other changes in the Chinese state) seem to have created new social spaces that encouraged the martial arts to evolve and adapt themselves in certain directions.

During the Tang dynasty very little martial practice existed that was not directly tied to the battlefield. Sword dances were popular, as was wrestling. But by in large the martial arts were an armed affair, and the weapons and techniques used by civilian guards or performers were not notably different from those employed on the battle field.

Lorge argues that during the Song dynasty this basic pattern began to break down. Regional militias and staff societies were important and their techniques varied according to geography and the local tactical situation. Still, the critical variable was the grown of permanent economic markets and the urbanization that this encouraged. Exotic weapons and flashy fighting techniques were increasingly used to entertain wealthy merchants. These skills may have been organized into lineages, and it is not clear that they always retained any practical value on the battlefield. Audience appeal was the new metric by which this class of performing arts was judged.

These trends continued in the Ming dynasty. Because Lorge does not engage in a deep analysis of any period boxing texts he has little to say on the mixing of Daoist health techniques and boxing which other scholars have traced to this era. However, he continues to see the association between the unarmed hand combat and various branches of popular entertainment as being important to their spread and development. He goes further than many other commentators in linking the evolving nature of the martial arts in this period to the spread of literacy and the creation of new literary forms (particularly the classic martial arts novels).

Scholars looking for deep original research may be disappointed with this section of the volume. Increasingly it seems that Lorge’s audience is either academics who know nothing about the Chinese martial arts, or students of the Chinese martial arts who know little or nothing about Chinese history. That is fine and there is certainly a need for this type of book. This book would make an excellent text in an introductory undergraduate class on the Asian martial arts, and I plan on using it once I get my course up and running.

I have always felt that is fundamentally unfair to criticize someone for not writing the book that I would rather have seen instead. There is room in the Chinese martial studies literature for more than one book, and there is certainly demand for a no-nonsense introductory text that can introduce new readers to the field. Still, I would have liked to see more of an argument, or theoretical apparatus, connecting Lorge’s discussion of the Song and Ming dynasties. Further, I would have been willing to sacrifice some of the general discussion in the earlier chapters for a chance to explore the development of boxing in the Ming dynasty in much greater detail. After all, that is precisely what most readers expect this book to do.

In the third and final post reviewing Lorge we will cover the Qing dynasty, the Post Imperial Period, and the Conclusion. Make sure you look these chapters over for next week.

To read the final post in this series, discussing Chapters 9-10 and the Conclusion, click here.

4 Pingback