Accepting the“traditional” Chinese martial arts as a product of the modern world.

If I were to conduct a pole and ask the average student of the Chinese martial arts when the “Golden Age” of Kung Fu was, what sort of responses do you think we would get? The Han dynasty? The high Ming? The 1700s? All of these would be wrong. There were fewer people studying anything that would look even remotely like the martial arts in China at those points in time than there are today, and by a quite substantial number at that. Village militia training has never been quite the same thing as the “martial arts.”

A few students of history, realizing that the modern Chinese hand combat styles are a lot younger than most people assume, might put forward some more reasonable guesses. Maybe they would place the “Golden Age” of Kung Fu in Shanghai in the 1920s and 1930s, or Taiwan in the 1950s and 1960s. These would be good guesses. They were certainly seminal moments in the development of the Chinese martial arts.

Nevertheless, I suspect the real “Golden Age” of Chinese martial arts didn’t start until 1982 and it ran through sometimes in the late 1990s. It is hard to imagine isn’t it. The traditional Chinese martial arts reached the pinnacle of their popularity, social acceptance, and (truth be known) quality, in the post-Cultural Revolution period. At least this is when their popularity seems to have peaked in mainland China. Places like Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan and the west are all on slightly different historical trajectories.

The 1980s and 1990s were remarkable decades. At no other point in Chinese history had so many people taken up the martial arts or done them so well. The current situation in mainland China is bleaker. Some things are going rather well. The martial sports, Sanda and performance Wushu (subsidized and protected by the government) are quite popular. Wushu may even be accepted as an Olympic sport at some point, though it still has a number of hurdles to overcome. And the idea of the“martial arts” remains a hot commodity with consumers. Lots of good books and movies are being produced. There is even an unprecedented outpouring of high quality academic writing on the history and sociology of Chinese martial studies.

Still, other developments look ominous. Due to increased competition and economic changes, enrollments are dropping in all sorts of “traditional” (non-Wushu) hand combat schools. Further, the market for traditional martial arts is being dominated by a handful of quickly growing styles that have managed to catch the attention of the media while other arts sink into obscurity. The future of Taiji Quan and Wing Chun seems secure. The ultimate fate of many other traditional arts is less certain.

In order to better grasp the changes that we are currently seeing, it is necessary to be able to put all of this in its proper historical perspective. The images that I selected for this week are designed to help us do that. They look back to the events that sparked the 1980s Kung Fu craze (in mainland China) and remind us that we are actually living in the first post-Golden Age generation of the Chinese Martial Arts. The declines that we are seeing now are not as deeply rooted as the popular imagination makes them out to be.

While subtle changes in the economy and society are important when attempting to understand these declines, on a fundamental level they have nothing to do with the “modernization” of China. When properly understood, it becomes apparent that the specular growth of interest in the Chinese martial arts in the 1980s and 1990s was itself a result of the modernization of the Chinese economy and the liberalization of society. When we look at the “traditional” arts that exist today, we are looking at a quintessentially “modern” phenomenon. While some of these arts may need to adapt, they remain fundamentally compatible with the modern world. The main question is, can they do it in time?

“The Shaolin Temple” Ignites a Kung Fu Craze

Both of our pictures today are original press photos taken by a press photographer in China in 1982. The newspaper industry has long since gone digital and it is often possible to buy original press photos on ebay for almost nothing as the old collections and archives are liquidated and smaller publications go under. I was quite lucky to find these. Both photos were in basically good shape, though the one with the three children was slightly damaged as can be seen in the scan below.

In 1982 the Hong Kong director Chang Hsin Yen released “The Shaolin Temple” staring Jet Li, a young Wushu performance champion. This was the first Hong Kong based martial arts movie to be filmed in China. More importantly, it was also the first martial arts film of any kind to be shown in China since the Cultural Revolution.

The Chinese government tightly controlled the film industry and attempted to improve the morality of the people by strictly censoring most portrayals of violence and nearly any allusion to sex. It must then have come as a shock to mainland movie goers in 1982 to sit down to a film and to be immediately thrown into a three hour orgy of Hong Kong style violence. All of this emotional energy within the audience was then linked to the martial arts, a topic that had been strictly forbidden only a few years before, and had been neglected in favor of more conventional western sports since the end of the Cultural Revolution. Add in a graphical revival of the traditional Shaolin mythology and Chang Hsin Yen succeeded in creating what was essentially dynamite on celluloid.

It is hard to overestimate how much of an impact “The Shaolin Temple” has had on the Chinese public. Gene Ching has rightly called it the “Star Wars of China,” but in some senses even that analogy falls short. Star Wars debuted at a time of national anxiety, after the loss of the Vietnam War, when Americans were questioning their values. The Shaolin Temple followed a much worse period of national disruption. The Cultural Revolution has been described as a period of collective national insanity for China. Jet Li’s performance dramatically closed the book on this hated chapter in Chinese history and was graphic visual proof of the increasing liberalization of society.

In short, by the time this film hit the street the traditional Chinese martial arts were primed for an explosion. The social energy unleashed by this film was so massive that it even reached the pages of the NY Times. In 1982 and 1983 the Times ran a couple of very interesting, and even insightful, articles on both the film and the broader revival of the actual Shaolin temple.

Shi Dechan, Guardian of the Wisdom of Shaolin

Like so much else in China, the monks of the Shaolin Temple had fared badly during the Cultural Revolution. The community shrank and many individuals were forced to flee into the hills and local communities to avoid persecution. The filming of this movie, using the actual temple as its backdrop and the aging community of monks as extras, signaled a new era of social acceptance and respectability for the monks. Shortly thereafter individuals began to return to the community and the long hard work of rebuilding could begin.

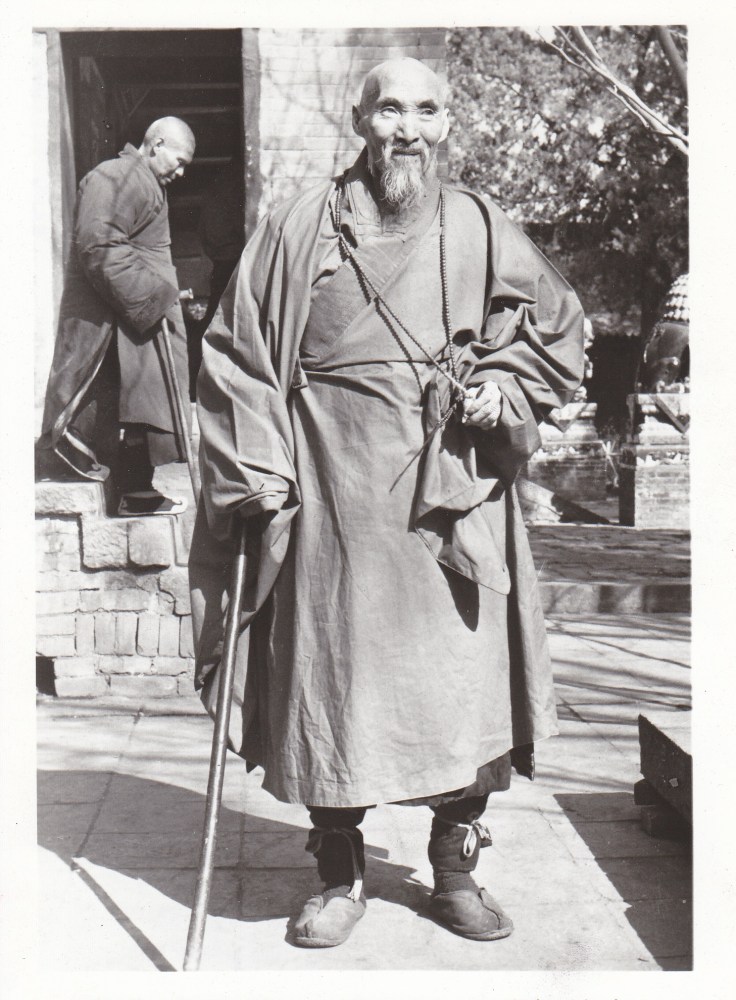

Our first picture is a wonderful portrait of Shi Dechan (b. 1907-1993), the acting or “honorary” Abbot of Shaolin. Today Shi Dechan is probably best known for the small cameo he was given at the beginning of the film where he can be seen welcoming foreign dignitaries from Japan. However, he made a number of other much more substantive contributions to the Shaolin community over the years.

Probably born in 1907 he was sent to the Shaolin temple in 1916 following the deaths of his parents. He was liked by his teachers and was eventually accepted as a member of the community. Shi Dechan’s specialty was always medicine. As a young monk he traveled to a number of different temples to learn Traditional Chinese Medicine, Qi manipulation techniques and Bonesetting. I have seen some sources that list him as a master of Xiao Hong Quan (Small Red Fist) but I have not been able to confirm this or to locate a list of his martial students.

Shi Dechan had the misfortune to see, and even lead, Shaolin through some of its darkest chapters. He returned to the temple from his medical studies in 1927, just as the conflicts during the warlord period was reaching a crescendo. He returned only a year before the Temple would be burned to the ground by a local warlord.

He was one of the few monks who remained at the community and assumed increasing leadership responsibilities. It seems that by the start of the Cultural Revolution he may have been the defacto leader of the remaining Shaolin community. I ran across the following reminisce in the obituary of another monk who survived the same period:

“In order to protect the cultural relics from future damage and loss, Ven. Suxi assisted the then honorary abbot of Shaolin Monastery, Ven. Shi Dechan in distributing a portion of the Sutras and inscribed tablets to each of the monks, ordering them to memorize them completely- even so far as the calligraphic style used to write them and their dates. It all had to be memorized accurately. That way after all had passed they could be recovered. After reciting and memorizing, the monks then buried the texts and statues underground.”

Shi Dechan also played a critical role in Shaolin’s modern history by serving as a Master and mentor to Shi Dequan. Dechan passed on to Dequan his vast knowledge of traditional Chinese medicine. Dequan later had the opportunity to attend a modern medical school but he practiced extensively in very poor areas with no access to modern pharmaceuticals and little equipment or support. He was forced to draw on the totality of his medical knowledge and local resources to help his patients.

Dequan’s life history is fascinating and I should probably profile him on our “Lives of the Chinese Martial Artists” series. Looking at the challenges that faced both him and his teacher, I can say with all honesty that you just could not make this stuff up. No one would believe you. Dequan is best known now as the author of the“Shaolin Encyclopedia.” This four volume, 1000 page publication, is the most complete database on monastic Chinese fighting systems currently available. It even includes a selection of texts that were copied by a monk who visited and left Shaolin in 1927, months before its original library burned to the ground.

The Children of Shaolin

One of the most striking things about any of the early pictures of Shaolin is the total absence of middle aged adults. Pictures from the early 1980s inevitably show a combination of aged monks and large numbers of young enthusiastic children, dreaming of being the next Jet Li. But the intervening generations are simply not there. Very few people outside of official sports training facilities were able to study traditional Chinese boxing during the 1960s and 1970s. Needless to say, the Red Guards of the Cultural Revolution also took a rather dim view of individuals seeking to following a religious vocation of any kind. These two decades constitute a “lost generation” in the history of the Chinese martial arts on the mainland, and nowhere is that void thrown into starker relief than in the photographic record of Shaolin.

If the resurrection of the Shaolin temple was a profound event for many of China’s adults, it became something of a mania for its children. Across the country elementary and middle school students quite literally dropped what they were doing, picked up a staff, and started studying Kung Fu. They overwhelmed the few existing schools within weeks and quickly sought out anyone who had any degree of prior training.

Nor was the struggling Temple prepared to deal with the onslaught of youthful enthusiasm it was about to receive. A New York Times article from 1983 notes:

“Shaolin’s monks today go about their duties with shaved heads and coarse gray robes, oblivious to the stream of tourists. But they also have tales to tell. Fu Yun, now in his 60’s, recalled how the monastery had 300 monks when he joined as a child novice in 1930. In those days, he said, the monks practiced wushu six hours a day as a respite from meditation. ”The basic lessons in wushu were to keep us fit,” said Fu Yun. He was forced to go home to work as a farmer in 1949 but returned after the Communist authorities adopted a greater tolerance for religious belief after the repressive Cultural Revolution.

To the disappointment of many visitors, the monks [of Shaolin] no longer perform wushu. ”I can still play but not very well,” Fu Yun confessed. ”To be good at wushu, you must be obedient and willing to bear suffering and hardship.” Chuan Qing, a 24-year-old monk from eastern China, said he was not interested in wushu because ”it is very hard to do.” For the monks, who rise at 3 or 4 A.M. and subsist on vegetables and rice, life is not much more glamorous than that in other Buddhist monasteries in Asia.

…..

Shaolin’s traditional martial arts are being preserved at the nearby town of Dengfeng, where a sports school specializing in wushu opened two years ago. Its 140 or so pupils practice wushu every afternoon following their academic classes. The pupils, some of whom are only 10 or 11 years old, frequently stage fighting displays for foreign tourists on the packed dirt of their outdoor practice field.”(“Of Monks and Martial Arts.” By Christopher Wren, NY Times. 11thSeptember, 1983. A. 41.)

Across China tens of thousands of children ran away from home, intent on traveling to Shaolin and becoming martial arts masters. It seems that most of these children never actually made it to the Temple, but they were a headache for police and school officials. Local lore in Dengfeng even states that the government had to commission special trains to ship the truant youth who managed to make the journey back home.

Still, this groundswell of the enthusiasm presented a business opportunity that could not be ignored. Just before the release of the movie, a Wushu school (basically a boarding school that taught martial arts to prepare students for careers in the police and military) had opened in Dengfeng. It was quickly overrun with students. More schools were rapidly opened by other shaolin disciples, monks and former novices. Currently most of these are located in Dengfeng, where they are an important part of the local economy.

The three children in this 1982 photograph would have been among the first to be accepted as students in the new extended shaolin community. What they lack in skills they more than make-up for in raw energy and enthusiasm. Note also the spartan, barracks-like buildings behind them. I am not sure but I suspect that these structures were their school. Even today Chinese students as young as 10 years old are sent to boarding schools in Dengfeng where they train under less than ideal conditions including little heat, bad food, substandard medical care and brutally long hours. The very best of these students are then invited to join the various “Shaolin” performance teams that often stage shows around the world. Most will end up in the military, local police forces or working for private security companies.

This image is interesting precisely because it captures the exact moment in history in which the modern “Shaolin-Industrial Complex” sprang to life. This was the place where the “Golden Age” of the Chinese martial arts was born. I must say that I find it remarkable that so many individuals within the field of Chinese martial studies are reluctant to talk about Shaolin. Often they claim that the Temple’s martial heritage is overblown and that it creates a distorted view of the traditional Chinese martial arts.

I suppose that in a limited sense all of that is true. It is mostly true if you are interesting in the pre-Ming era fighting arts. But it also manages to ignore the rather inconvenient fact if it were not for the “rediscovery” of Shaolin in the early 1980s the “traditional” Chinese martial arts would never have gone into revival in mainland China. If not for Shaolin, how many of us would even be talking about Chinese martial studies at all? A little credit where credit is due. The “traditional” Chinese martial arts are a modern revival and re-imagination of the ancient past. Not only is that true today, it was even true of the revival of interest in hand combat at the end of the Ming dynasty. The Shaolin temple, both as a place and as a myth, has played a central role in both of these episodes. Its contributions deserve very careful study.

February 12, 2015 at 9:50 am

I believe you are talking about Shi Deqian.