Chan Wah Shun and his Place in the Modern Wing Chun Community.

One of the biggest problems in researching the history of the martial arts is the martial artists themselves. They love their styles (or the businesses that they support) so much that everything needs to have an elaborate back story. A straight forward account of the first guy to open a Wing Chun school is not enough. Instead we need a tale of mystery, adventure, and potentially traitorous opera-singing terrorists. Even though all of the evidence points to Wing Chun being an indigenous creation of Southern China, there is an almost irresistible urge to tie the art to some great legendary figure of the “Central Plains.” Whether it is Ng Moy, Tan Sau Ng or General Qi Jiguang is almost besides the point. All of these stories are responding to the same basic social needs, and ignoring historical reality.

Why is this a problem? If you are an amateur martial artist and these sorts of myths give you a vocabulary to think about your own journey of personal transformation they are not an issue. If, however, you are a historian or a social scientist attempting to understand the rise of modern Chinese civil society by watching the growth and the evolution of the market-place for hand combat instruction, now we have a problem. The truth is that Wing Chun is not nearly as old as most people assume. Its creation story probably dates back to the 1920s or 1930s. The body of techniques it is based on were probably first brought together in one place by Leung Jan in the mid-19th century. But how old is it as a “martial art”?

That is a tricky question to answer. There is something undeniably subjective about it. Martial artists in Southern China have been using the basic structures and short-boxing theory of Wing Chun since at least the end of the Ming Dynasty. The basic concepts and movements seen in the “six and half point pole” are probably a good deal older than that. However, “Ng Moy” as the patron saint of the art dates to the 1930s, which is also the first time that the art gained real popularity in Foshan.

To help solve this dilemma I think we need to be more specific about what a “martial art” actually is (at least in the modern Chinese context). There is a difference, for instance, between being a martial artist and a military trainer. Many martial artists occasionally worked as trainers, but they are clearly not the same job and no one treated them as such. Both jobs focus on basically the same military skills and techniques (at least in the late 19th century). Both soldiers and traditional martial artists studied archery, horsemanship, pole fighting and fencing. The difference was that the martial artists did this within a social context that was explicitly geared toward the preservation and dissemination of these skills in the future. There is an interesting “educational” aspect to the Chinese martial arts (probably influenced by Confucianism). The army was never intended to act primarily as a school. When one trainer got old and retired you hired a new one. What was “eternal” was the military unit not the techniques of its combat instructors. These could actually vary quite a bit.

And this, in a nut shell, is why we need to pay a lot more attention to Chan Wah Shun, and a lot less attention to shadowy revolutionary figures or even Leung Jan. The good news is that Chan Wah Shun is a figure that we know a fair amount about. Unfortunately we cannot say the same for Wong Wah Bo, Leung Yee Tie or Painted Face Kam.

Almost all of us encounter Wing Chun as a “martial art,” not a random collection of military skills. That is probably what Leung Jan had. He probably got one set of skills from the Leung family school, and another from his contacts in the opera world. This was old, authentic material. Yet it was probably Leung Jan that combined them and shaped them into a form that we might find recognizable today.

What he did not do was to seriously teach his art and that is why, in a purely social-scientific sense, it does not make much sense to view him as the founder of “Wing Chun.” Yes it might be Chinese social tradition to do so, but “social tradition” is sometimes not that helpful to a historian. Wing Chun exists as a social community, and Leung Jan did not create that community. He contributed a valuable body of techniques to it. But he refused to teach anyone other than his two children and a single colleague from the market place.

Students today usually view this as some sort of supernal mystery. Or we assert (with no actual evidence) that Leung Jan was just “very conservative” and that he intended for Wing Chun to be a “family style.” Given that no one in his family ever opened a school, or even taught their own kids, that seems highly unlikely.

Here is a much more likely scenario. Leung Jan was a really successful businessman and a respected doctor. Boxing was popular in Foshan, but it was never seen as “respectable” by most of his patients. Plus it was a hard skill to monetize given how the economy was structured for most of the 19th century. Then there was the very real economic and social conflict that seemed to accompany the martial arts in Foshan during the 19th and 20th centuries. In fact, the martial arts are basically a tool for affecting the outcomes of “social conflicts.” Leung Jan didn’t have a dog in that fight. He had nothing to gain by teaching, so he didn’t. This is a pretty similar story to the one that we can tell about Ip Man prior to 1950, or Yeun Kay San. It should not be that farfetched to assume that the same basic mechanisms were at work in Leung Jan’s life as well.

Chan Wah Shun was in a different situation. By the end of his career the local economy had evolved. More transactions were monetized and more modernization had happened. There were suddenly a lot more ways to make cash money with your martial arts skills. A Chinese hand combat school from 1900 still looks pretty different from one today, but we are now well on that path. Besides, the great commercial success of the Hung Sing Association (also located in Foshan) gave Chan Wah Shun a model for how this could be done.

This allowed him to open a school that taught people who were willing to make a serious monetary investment, either because they came from well off families (the only sorts that had spare silver laying around) or because they anticipated getting a job as a security guard (sort of like paying for an associates degree at a community college). It was a good plan, except for the timing. The Boxer Uprising in 1900 nearly destroyed the Chinese martial arts and made them deeply unfashionable among exactly the student base that Chan Wah Shun was trying to reach. Even the venerable Hung Sing Association was forced to close its doors during this period.

So once again, rather than assuming that he was “very traditional” in his selection of students (something which there is no actual evidence to support) we might better understand the small size of his school as a combination of bad luck and a business model that was a bit before its time. Still, Chan Wah Shun laid the foundations for the growth of Wing Chun in the 1920s and 1930s. Without him it is unlikely that anyone would have heard of this art or that there would be much desire for it today. Chan Wah Shun was the first person to attempt to publicly teach Wing Chun and he shaped it into a true “martial art.” I have always believed he deserves more careful study and respect than he gets.

Below is a brief, two page, sketch of his life from my forthcoming volume (co-authored with Jon Nielson) A Social History of the Southern Chinese Martial Arts: Identity, Conflict and the Creation of Wing Chun. I have shortened the account, eliminated the detailed discussion of his students and taken out the footnotes to make it more suitable for a blog post. Still, I hope there is enough information here to inspire some good conversation. If you want to read more, it will all be there in the upcoming book:

Chan Wah Shun and the Foshan Wing Chun Tradition: A Biographical Sketch

In the words of Ip Man “Leung Jan grasped the innermost secrets of Wing Chun and attained its highest level of proficiency.” While it remains unclear how many students he actually taught in Foshan, there can be no doubt as to which of his disciples was the most influential. It was Chan Wah Shun (1849-1913) who transformed Wing Chun into a public art.

In doing so he was following the trend previously established by local schools like the Hung Sing Association. This group taught Choy Li Fut and was the largest and most important public martial arts school in Foshan. While the school was reformed and reopened by Jeong Yim in 1867 (following the Red Turban Revolt) it was once more forced to close in 1901 due to the Boxer Rebellion. It is interesting to note that Chan Wah Shun’s move into the public sphere happens just as the Hung Sing Association reopens its doors.

While Chan Wah Shun gained a fair degree of notoriety in local martial circles, there are still many unresolved questions regarding his early life. Leung Ting places his birth in the year 1833 while Huang Xiao Hui and Huang Hong favor the year 1849. Given the importance of the events of the 1850s, this decade discrepancy has quite an effect on how one might imagine Chan’s early life and formative years.

This uncertainty might be impossible to definitively resolve, but we may still be able to state which of the two scenarios is more plausible. If Chan Wah Shun was born in 1833 and he began to practice Wing Chun when he was 25 (as Leung Ting asserts) then he would have commenced his studies in 1858. Given that Leung Yee Tai and Wong Wah Bo probably did not seek refuge with Leung Jan until 1855-1856 this raises some difficulties. First, one wonders whether Leung could really have learned enough in two years to take on students. Secondly, in 1858 the opera ban was still in place and much of Foshan was in ruins. Given that Wong Wah Bo and Leung Yee Tai were both still around, and supporting themselves by teaching martial arts, it is not clear why Chan Wah Shun simply did not go to them (or one of their associates) instead.

If we accept Leung Ting’s assertion that Chan was about 25 when he commenced his studies, but instead assume that he was born in 1849, he would have begun his training in 1874. By this point in time the opera singers would have moved on and Leung Jan may have had an opportunity to establish his reputation in local medical and martial circles. While either set of dates could work, this second possibility seems more plausible.

Throughout the course of his life Chan had a varied career. He was born in Manin Village in Shunde. As we have already seen, this was a generally conservative farming region characterized by rich landlords and strong local gentry. It was also known for its strong militia organizations which hired such luminaries as Chan Heung (the creator of Choy Li Fut) to act as trainers and drill instructors. We can probably assume that Chan was first exposed to martial arts as a child.

At the age of 13 Chan was sent to work at a rice shop in Foshan. Later he started a business as a moneychanger in the market place (where he first met Leung Jan) and acquired the nickname “Moneychanger Wah.” While silver was the official tender, smaller transactions were carried out with copper or bronze coins. In any quantity these could be quite heavy, but Chan was known for his height and strength.

Exactly how Chan was first introduced to Wing Chun is subject to some debate. The standard Ip family story is that he ran a money changing stall outside of Leung Jan’s pharmacy. He was unaware that his neighbor was a martial arts master until one day (while taking shelter from the rain) he discovered Leung Jan teaching his sons and begged to be accepted as a student. Huang Xiao Hui and Huang Hong instead claim that Chan Wah Shun was first taken on as a student by Li Hua (or “Wooden Man Hua”) who was himself a student of Leung Jan. Chan studied with him until his death, at which time he began to learn from Leung Jan himself.

In addition to martial arts, Chan Wah Shun also inherited Leung Jan’s medical skills. He eventually became an accomplished bone setter and herbalist in his own right and went into practice for himself. He even assumed many of Leung Jan’s duties as the old master prepared for retirement in 1895. Ip family lore also claims that this is when he began to teach Wing Chun publicly. While Leung Ting relates a number of stories of Chan Wah Shun teaching students much earlier (usually while keeping the relationship secret from Leung Jan), the more common accounts state that Leung Jan did not wish to teach martial arts publicly, and hence Chan Wah Shun could not. However, immediately upon his master’s retirement Chan Wah Shun began to accept students.

Chan was the first individual to teach Wing Chun publicly, yet he faced a number of distinct challenges. To begin with, he suffered a stroke and retired in 1911, meaning that at most he only had a 15-16 year teaching career. Further, the Boxer Rebellion in 1900-1901 caused general chaos and damaged the reputation of hand combat schools across the country. The provincial government closed martial arts studios throughout Guangdong in 1901 in a bid to prevent copycat attacks on foreigners. They quite correctly perceived that any provocation might give the British naval squadron stationed around Hong Kong a pretext to seize the entire Pearl River.

The legacy of the Boxer Rebellion proved to be toxic to China’s traditional hand combat community. At a time when the Chinese people were actively contemplating the future and far reaching political and social reforms, martial artists appeared backwards, feudal and superstitious. In short, the traditional modes of hand combat came to embody all of those values that the nation was moving away from. It would not be until the 1920s that a new generation of more urban and intellectual martial artists would arise and argue (successfully) that the traditional arts could be a key element of China’s modern identity.

This historical background should help to frame our understanding of Chan Wah Shun’s efforts to spread Wing Chun. Between 1895, when he first began to publicly accept students and 1901, when the government suppressed martial arts schools and associations, Chan would have had at most five years to gather and teach his pupils. This is barely enough time to instruct a generation of students in the Wing Chun system. Other schools in the area resumed instruction somewhere between 1903 and 1905, so it seems safe to assume that this is probably when he reopened his doors as well. Chan Wah Shun only had a little over six years to train the rest of his disciples at a time when the popularity of traditional boxing was at an all-time low and his health was starting to fail.

When we combine this with the fact that Chan charged a considerable amount of money for instruction, it is not that hard to understand why, according to Ip Man, he only had about 16 students. The small size of his school accurately reflects the marginal position that traditional modes of hand combat occupied at this point in time.

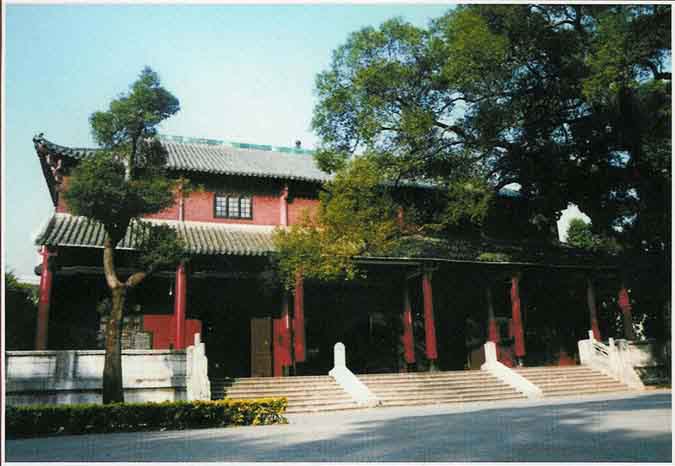

Little to nothing is certain about Chan’s first period as a teacher. However, after the dust settled from the Boxer Rebellion it is known that he approached a prominent local businessman and landlord named Ip Oi Dor (Ip Man’s father) and rented space in the Ip family temple to conduct his classes. His students were not great in number but must have come from the better elements of society if they could afford the entrance fee of 20 taels of silver as “Red Envelope Money” and an additional 8 taels of silver in monthly tuition. This was much more than the Hung Sing school charged its members and it reflects the high degree of correlation between different hand combat schools and Foshan’s radicalized class structure. Wing Chun truly was, and would remain for much of the 1920s-1940s, a rich man’s game. Even with these structural restraints, the art gained more public exposure during this period than it had ever enjoyed in the past.

While Ip Man asserts that Chan Wah Shun taught as many as 16 students we have not been able to locate a list that is both complete and credible. Huang Xiao Hui and Huang Hong, in their chapter written for Ma, go farther than any other source listing a total of 11 direct students. Their brief biographies of Chan’s students and grand-students helps to paint a fascinating picture of life within Foshan’s Wing Chun clan from the 1920s-1940s. Given that Chan’s teaching happened in two distinct eras, separated by an abrupt break, it is perhaps not surprising that it is so difficult to assemble a complete class roster. Following Chan’s retirement in 1911 he returned to his native village in Shunde where, according to local tradition, he passed on a distinct version of his art that can still be seen today. Given his overall condition and short time to teach, it is unclear what Chan himself was able to convey. Of course some of his other students were also in the area.

August 8, 2013 at 7:07 am

Another intriguing well researched and well thought out piece, I was trained by a Hong Kong Master {Fung Chuen Keung} that did not believe the back story himself but perpetrated it out of his respect for his Master {Chu Shong Tin}. I am not personally a scholar of Asian Martial Arts, with the obvious exception, I know precious little about Chinese social history and as such it has always been impossible for me to come to terms with the stories. Your insights into the place of the Stories in the everyday lives of Chinese Martial Artists has allowed me to look at these tales in a very different and less scornful manner.

Thank you.

Derek

August 8, 2013 at 2:38 pm

Thanks for dropping by! I am glad that you liked the post and found it helpful. I do a lot of history, but at the same time I still think that there is a lot of meaning in these stories, if viewed in their proper context.

February 4, 2015 at 8:37 pm

Very convincing and in accord with my understanding of Chinese culture! I look forward to the complete text of your book (published in August?).

I am very interested in the juxtaposition which occurred when this aristocrat’s art mixed with the blue collar kids of the inner city of 1950s Hong Kong, producing street fighters like Wong Shun Leung and Bruce Lee. It is this mix of brawler’s determination and grit with the refinement of the high-level concepts and skill set that make this fighting craft so unique (and effective in the right hands).