The TCMA as a Perpetual Revival Movement

Kung Fu has an odd relationship with the past. It seems that for the last century (at least) each generation has discovered the beauty of the Chinese martial arts only to realize that they are quickly “dying out,” and will likely succeed in doing so unless steps are taken. In other words, there is a strain of the Chinese martial arts that exists in a state of perpetual revival. This is not just to say that each generation must discover these arts for themselves, but that the very language of “loss” and “preservation” are inherently bound up in this process.

Once we understand this, we come closer to grasping the social meaning and function of these practices throughout time. This same discourse seems to be deeply meaningful in our own era. In striving to preserve an ‘authentic’ aspect of martial history, practitioners find something equally authentic within themselves. It may be an increased awareness of their Chinese heritage, a sense of self-creation and empowerment, or simply the awe of touching a relic from humanity’s deep past. After all, few things in our daily life claim to be as ancient as Kung Fu.

Recently I was struck by the notion that not only is there a degree of regularity in the on-going rediscovery of Kung Fu, but that certain rhetoric regarding its social meaning and significance also reappears, with surprising regularity, over the decades. Each generation is bound to rediscover, more or less, the same thing about Chinese masculinity, whether it is embodied in Huo Yunjia, Bruce Lee or, more recently, Daniel Wu. Not only have these individuals carried the same symbolic torch, but they have even been discussed in broadly similar terms by their contemporaries.

This is not to say that they have all played identical roles. Ideas about gender, nationalism and identity are in constant flux. Change is a vital part of this process. Still, the similarities between them are interesting enough that it causes one to stop and think.

The need to look into the past and discover something of value, an idea or symbol that will point the way to a better future, is not confined to the present moment in history. This seems to be an almost universal impulse. Perhaps we enthusiastically rediscover similar inspirations in the lives of each of these figures because there is a ‘Kung Fu shaped hole’ in the human soul?

Alternatively, if we dig deeply enough we will find that the archaeology of popular history and media provides valuable insights into the motivations and meanings driving the current embrace of the Chinese martial arts. The fact that each generation is compelled to “discover” so much anew also mandates that much must also be “forgotten” just as regularly. I personally find the odd forgetfulness that surrounds the contemporary history of the Chinese martial arts to be one of their most fascinating traits. Yet one still suspects that deep currents of discourse from the past shape at least some attitudes in the present even if most of us remain blissfully unaware of this cultural inheritance.

For this reason I am always looking for clues as to how the Chinese martial arts were perceived within the ‘trans-national’ or ‘global’ community prior to their rediscovery in the 1970s. It is tempting to allow our impressions of these attitudes to be shaped by the narratives of popular Kung Fu films in which Western forces were always implacably hostile to the Chinese martial arts. These practices were, after all, tasked with defending the nation’s dignity against the forces of imperialism and spiritual colonization.

Nor is it all that difficult to find racist or bigoted accounts of the Chinese martial arts. Still, it is interesting to note that many of these hostile accounts date to the middle or later periods of the 19th century. This was an era of active military conflict throughout the region and doubts about the Qing government’s ability to adapt to its rapidly changing environment.

By the second and third decades of the 20th century there was a notable change in foreign language discussions of the Chinese martial arts. The main sentiment expressed by these writers was one of mild curiosity rather than derision. And a notable percentage of western authors were inclined to see positive values and potential strengths in these systems of boxing and gymnastics. (Readers should recall that the Chinese hand combat systems were rarely referred to as “martial arts” in the pre-WWII period).

The following Research Note includes two articles found in Hong Kong’s English language newspapers written nearly a decade apart. Both are interesting in their own right and introduce some important facts about the period in question.

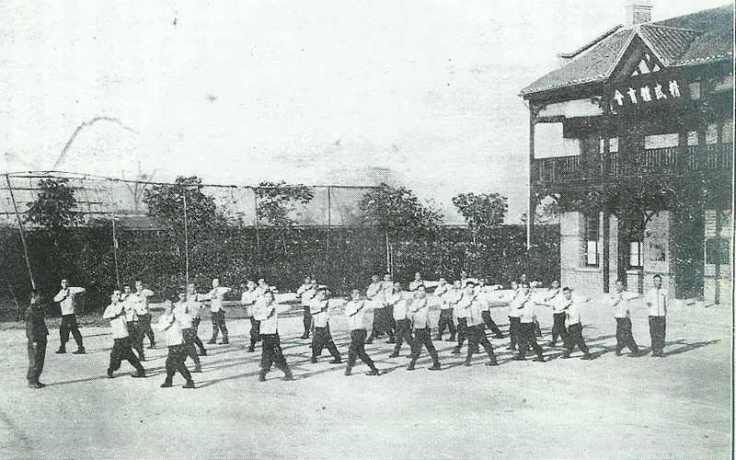

The first documents a Jingwu (Chin Woo) demonstration at a local school. This specific organization did much to promote the practice of the Chinese martial arts among students during this decade, spreading their base of support widely throughout society. Readers should also note that this article follows Jingwu’s linguistic convention and uses the term “Kung Fu” as a label for the traditional Chinese martial arts. This usage provides further evidence reinforcing certain arguments about the historical evolution of the term that I made here.

The second article reminds us of the importance of court records and legal proceeding as historical resources. It is a notice of charges against a Kung Fu teacher in Kowloon for the possession of unregistered weapons. The brief nature of this account raises as many questions as it resolves about how the martial arts community interacted with law enforcement during the 1930s.

The police appear to have had no interest in pressing charges against the Sifu as they were aware that the weapons were only used in teaching, and the judge dismissed the case as a technicality after imposing a minimal fine. Still, one wonders why the instructor was dragged into court at all for a weapons offense that no one was interested in enforcing. We know that during the 1950s-1980s there was a degree of hostility between the Hong Kong police and traditional martial arts schools, whom they often viewed as fronts for organized crime and Triad activity. Cases such as this one raises the question of how far back these tensions went.

Taken together these articles seem to illustrate a more nuanced reception of the traditional Chinese martial arts on the part of Westerners in southern China than current popular culture troupes might lead one to suspect. Their attitude was not always one of derision or implacable hostility. Jingwu’s involvement with the education of the youth was seen in a generally positive light. Both the police and presiding judge in the second account seemed capable of distinguishing the social function of the Kowloon school as a place of instruction from any technical infractions of weapons regulations that existed at the time. As a set these articles shed light on how the Chinese martial arts were being discussed and imagined prior to their “re-discovery” by the English speaking world in the 1960 and 1970s.

CHINA’S YOUNG IDEA

The China Mail, Page 4

2/25/1924

What the “Chin Woo” is Doing.

Unique Show at Queen’s College.

Small Chinese boys whirling huge swords around their heads and, grotesquely costumed in clownish rigs, performing quaint ballet. Chinese flappers swinging an equally nimble blade and then dancing a graceful pas a deux—these were some of the sights seen in the hall of Queen’s College yesterday afternoon, when prominent members of the Chin Woo Athletic Association gave a demonstration of the form of physical culture which it is their purpose to persuade the young people of China to take up.

It was altogether a unique show. The hall was filled with scholars from Queen’s college, who applauded the performances with much warmth, and members of the teaching staff, who looked on with evident interest. Under the genial supervision of Mr. Tang, a squad of boys kept the fry occupying the front “stalls” in a permanent state of apprehension by their smartly performed evolutions with a sort of Chinese claymore and following this came a vimful exhibition of kung fu, or Chinese boxing.

Mr. Lo Wei-tsong, one of the directors in Shanghai of the Chin woo, who had earlier explained to the gathering the objects aimed at by the system of physical culture the association teaches, proceeded to practice what he preached by demonstrating, with the help of Mr. Yao Shur-pao a number of useful holds and grips which might be used in self-defence. Clad only in tiger skins they looked a picturesque pair and certainly proved themselves exceedingly capable exponents of their art.

But the piece de resistance, as far as the audience was concerned, was unquestionably the comic ballet in which half a dozen Queens College boys participated. Dressed as clowns, they wore absurd masks and their antics made them appear for all the world like a collection of mechanical toys. The basic principal underlying this performance is that it must be done to music and it said much for the training of the youngsters that, owing to the fact that someone had lost the key of the cabinet containing the musical instruments, they did their “turn” remarkably well without other accompaniment than a sort of sing-song chant by their instructor. Later when one of the “property” swords had been requisitioned to break open the music box, and the musicians had fished out their instruments, clamorous demands for an encore were yielded to and they repeated their quaint performance with added gusto.

How far the modern young woman of China has succeeded in overstepping the bounds previously imposed upon her by prejudice and tradition may be gauged from the fact that three Chinese girls from Canton took part in the programme and followed an exhibition of swords dancing and kung fu with something rather less martial in the shape of an elegant minuet with which their juvenile audience was obviously, as one of the lady teachers put it, “tickled to death.”

As an exhibition of Chinese Calisthenics the performance was extremely interesting and the Chin Woo Association whose motto appears to be something like our own mens sna in corpore sano deserve high praise for their efforts in this way to advance the physical development of China’s youth. Thanks expressed by the headmaster (Mr. B. T. Tanner) to Mr. Lo Wei-tsong, and cheers for all concerned ended a highly entertaining afternoon.

POSSESSION OF WEAPONS

Hong Kong Daily Press, Page 11

5-28-1938

CHINESE BOXING INSTRUCTOR FINED

Ng Hak Keung, boxing instructor of the Yuk Chi School and the Ching Wah Boxing Club, was charged before Mr. Macfadyen at the Kowloon Court yesterday with possession of three swords, two daggers, four spear heads and four fighting irons.

Dept.-Sergt. Pope said that the weapons were used for instruction purposes and the police were not pressing the case.

Defendant said that he was under the impression that as the blades were not sharp he need not have a licence.

His Worship remarked that it was only a technical offense, and fined the defendant $10.

oOo

If you enjoyed this Research Note you might also want to read: The Invisibility of Kung Fu: Two Accounts of the Traditional Chinese Martial Arts

oOo

January 25, 2016 at 11:59 am

Liked the article, thanks.

Could be interesting discussing this matter with Sifu Daniel Docherty form London, who is a well articulated HK lineage TJQ practitioner that was a police officer there at the time.