Warning: Speculation Ahead

No topic surrounding Wing Chun elicits more interest than its deep historical origins. Did the art really originate at the southern Shaolin Temple? Was it connected to late Qing revolutionary groups? Did Leung Jan actually learn the system from a pair of retired Cantonese opera performers? And if so, what was this style doing on the Red Boats, whose performances were better known for their elaborate costumes and entertaining acrobatics than actual fighting efficiency?

At the same time the Mook Yan Jong, or “wooden dummy,” has come to define Wing Chun’s image in the public imagination. For actual students of the system, dummies are an aid in refining everything from footwork to the geometry of the perfect punch. But to the public they seem to have become the ultimate symbol of esoteric martial prowess. Increasingly they are showing up in all sorts of unlikely places in popular entertainment (including in a recent episode of Star vs. the Forces of Evil titled “Monster Arm”).

It is probably no coincidence that Wilson Ip opened his 2008 hit film Ip Man with a scene of his eponymous protagonist working away on his jong. How better to advertise his esoteric skills than by showing his mastery of a training tool that recalls the memory of the sinister room of “wooden dummy men” featured in so many Shaolin temple myths and kung fu movies?

Wing Chun is far from the only Chinese art that employs dummies. These training tools come in a variety of shapes and sizes and can be seen across the history of that country’s fighting styles. Yet there can be no denying the rapid rise in popularity of the type of dummy favored by Ip Man and Bruce Lee. Given that this particular training tool has become a ubiquitous symbol of Southern China’s martial heritage and culture, it might be worthwhile to consider the question of its actual origins.

How might the sorts of dummies currently used in Wing Chun have evolved? Where do they fit into the mythic and more historically grounded genesis of the style? Given that even the most romantic accounts of this art place its genesis only in the late Qing dynasty (18th or 19th century), and the fact that we don’t have any evidence of this type of dummy being used in earlier periods (say the Ming dynasty), it might be possible to make some headway on these questions.

Still, caution is required. We have few concrete sources on the origins of Wing Chun, and even less on the evolution of its particular style of wooden dummy. This lack of evidence makes it difficult to conclusively falsify theories, and arguments “made from silence” can never be considered wholly reliable. Barring some unforeseen discovery in the next couple of years, this is a subject that must remain speculative. The best we can do is to try out some reasonable theories and see how well they stack up against our understanding of other areas of Chinese history. On the other hand, a blog like this might be a great place to explore some of these “thought experiments.”

Red Boats and Wooden Dummies

So where does popular mythology locate the origin of the wooden dummy? For the most part this has not been a major topic of speculation. But many Wing Chun practitioners are certain that dummies were in active use during the era of the Red Boat Opera companies. Scholars of southern Chinese popular culture know that these groups plied the waters of the Pearl River Delta in specially built river junks between about 1870 and 1938.

Some accounts place the ultimate origins of the Red Boat system as far back as the 1850s, but given the strictly enforced vernacular opera ban that was put in place after the failed Red Turban Revolt, Barbara Ward (who has probably done more work on the subject in the English language literature than anyone else) concluded that they did not actually become a common sight until the early 1870s. Nor does the Red Boat tradition seem to have survived into the post-WWII era. During these prosperous years opera performances became a big enough business to be housed in permanent theaters and the older nautical traditions were abandoned.

Wing Chun students who look back to Cantonese Opera as a critical link in the transmission of their system often assert that dummies were either part of the ships rigging or were actually mounted on the specially built (and highly uniform) fleet of Red Boats. Opera students are said to have used them in both their basic training of performance skills as well as in their pursuits of the higher reaches of Wing Chun system. In fact, the Red Boats are often imagined as floating martial arts schools.

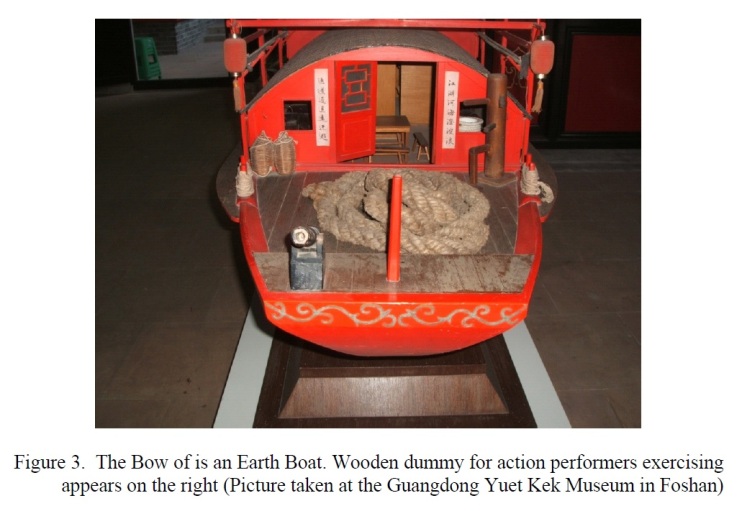

Nor are martial artists alone in perpetuating these images. The Cantonese Opera Museum in Foshan contains multiple references to the traditional role of the Mook Yan Jong in performance training. The museum even displays (a somewhat historically inaccurate) “scale model” of a classic Red Boat that clearly has a training dummy mounted on the rear deck.

It also has in its collection a vintage “buried dummy” (the more traditional type used prior to the 1950s). The museum’s description of this particular jong notes that “beating the wooden instrument” was a standard part of the training for all beginning opera students. So was the classic Wing Chun dummy simply inherited from the Red Boats and or other operatic traditions?

Possibly, but there are a few problems with this theory that need to be carefully considered. First off, this story doesn’t really explain the ultimate origins of these training tools. It just moves the problem one step back. Secondly, there are actually a number of practical questions that arise when we try to place wooden dummies in the context of what we actually know about these vessels.

To begin with, most of the accounts that “remember” the use of dummies on the Red Boats were recorded after the 1980s, in the post-Bruce Lee era, when Wing Chun was already growing in popularity. However, when one looks back at Barbara Ward’s work interviewing hundreds of opera performers and fans in the post WWII-era, no one seemed to remember the presence of wooden dummies on these vessels at all. Ward did not include them in her reconstructions of these vessels, which are probably the most detailed and reliable that we currently have.

Even more basic problems arise when we consider what life on these vessels was really like. The conditions for the both the opera troop as well as the vessel’s sailing crew were appalling cramped. The situation was even worse when one remembers to account for all of the costumes and other material that had to be carried from one performance venue to the next. In fact, the surviving members of the Red Boats that Ward interviewed all claimed that no training of any kind happened on these vessels. There was not enough room to move.

Then again, it would also have been basically unnecessary. The Red Boats were never intended to be blue water vessels undertaking long voyages. These river barges were somewhat akin to a large tour bus that would move from one town to the next as they worked their way up-stream during the performance seasons. Voyages might take a day or two, and then they would dock for three days or more. Any actual training or practice happened on dry land.

In my opinion deck mounted dummies seem unlikely. They would have been in the way of the crew when the ship was underway, while also being in the wrong place for actual martial arts and performance training when it actually happened on land.

Looking Further into the Nautical Origins of the Jong

I have always been a bit skeptical of the typical story linking the Wing Chun dummy to the style’s supposed origins on the Red Boats. While it seems entirely likely that Cantonese Opera performers used jongs, something has never really added up for me about the sorts of reconstructions that are imagined. Does this mean that we can dismiss the nautical origins of the Wing Chun dummy? Probably not.

I was recently part of a discussion regarding a southern kung fu style that also claimed an operatic origin and used dummies. One of the individuals mentioned that while he was a northern stylist, he had grown up around sailing vessels, and it would not be hard for him to imagine that these dummies might be descended from some of the deck machinery that he had seen.

This struck me as an interesting comment but having no familiarity with sailing vessels myself I didn’t know what to do with it. While thinking about this comment a few days later it occurred to me that I knew someone who could speak directly to this issue. Dr. Hans K. Van Tilburg, the maritime heritage coordinator for NOAA, is one of the foremost authorities on the naval architecture of 19th century Chinese sailing vessels. He also offered some generous advice on a couple of posts dealing with the martial arts and maritime culture posted here at Kung Fu Tea last year.

I gathered a number of pictures of various Wing Chun dummies (including the image at the top of this post) and emailed them out to him asking what he thought they were. His response was both immediate and fascinating. In his opinion the dummy in this often reproduced (but really somewhat mysterious) image is clearly a ships windlass which had been taken out of its mounting and propped up vertically. He also noted that the modern dummies bore an uncanny resemblance to the same sorts of windlasses.

These simple pieces of deck machinery were common on all traditional Chinese sailing vessels in the late imperial period. They might vary in size and configuration depending on the job that they were expected to do. Generally they consisted of a horizontal barrel or trunk that rope was loaded onto in order to hoist sails, anchors or the rudder (many Chinese junks of the period could raise their rudders when sailing into shallow waters). These trunks were fitted with a progressive series of holes or slots that held detachable wooden arms. These could be either long or short and were used by the sailors to hoist and hold the load.

Sometimes the holes were arranged so that if two arms were inserted at one time they would make an acute angle (much like a modern Wing Chun dummy). This was important as not every Chinese windlass had a gearing or locking mechanism. Instead an individual arm could be wedged against the deck to hold the load in place.

Above one can find a photograph of a relatively small and simple example of such a machine on a Vietnamese fishing junk. This image is particularly useful as you can actually see how rope was loaded onto the barrel to lift a load. The trunk of this windlass is octagonal, whereas all of the pictures I have seen of Chinese examples are round. [This leads me to wonder what an octagonal dummy would be like to work with?] Readers should also note that it seems to have three sets of “arms” which, if one were to set the trunk up vertically, would correspond to the high and low arms plus the leg. In fact, the individual employing the windlass as a dummy in the first picture is actually using the lower most “arm” as though it were a “leg.”

Another important image comes from a 19th century engraving of the aft deck of the Keying. We already encountered the Keying in a previous post. Used as a floating cultural exhibit it was responsible for the first public Kung Fu demonstrations to Europe in the 1850s.

In this image we can see an individual sitting on the windlass used to lift the sail. In this instance the arms have been removed and no rope is loaded on the barrel. As a result we can see the large diameter circular trunk with a configuration of slots or holes not totally unlike the inverted triangle still seen on the modern Wing Chun dummy.

Still, the Chinese windlass was always installed and used in the horizontal position. After the introduction of European sailing vessels into the water of southern China some vertically mounted machinery, referred to as a “capstan,” began to be produced. This type of arrangement was much more common on European vessels.

Needless to say, a vertically mounted Chinese-style windlass would bear an uncanny resemblance to a modern Wing Chun dummy. In the 1867 volume Notes on Japan and China, Vol. 1-2 (edited by N. B. Denneys, Hong Kong: Charles A. Saint) we read:

“Where a mechanical contrivance for raising an anchor is necessary, the old fashioned principal of the winch is usually seen in force: but the foreign capstan is gradually gaining ground in this respect.” P. 170.

While the vertical capstan may have gained ground in some quarters I was unable to locate a single image of one in all of the pictures and postcards of Chinese junks which I saw. Indeed, it seems that the windlass remained the machine of choice throughout the period of traditional boat building and even into the post-WWII period.

There are a few other bits of Chinese naval architecture that also seem suggestive of the structure of a wooden dummy. The long curved “leg” of a jong is one of its most striking visual features, yet there is nothing like that on any image of a windlass that I have located. However, the masts of Chinese vessels were often reinforced and braced with “legs” of very similar shape. The size of this appendage could vary tremendously depending on the scale of the vessel and the mast that was being supported, but the basic resemblance to a more traditional planted dummy is notable.

What of the Red Boats of the Cantonese Operas? All of the images that we have seen so far have come from either very large blue water vessels or fishing junks. Did the sorts of junks and barges that plied the Pearl River also have these sorts of deck machines?

Logically one would expect that the answer to this would have to be yes. Any ship which needed mechanical help in raising the anchor or hoisting sales could have used the services of a windlass or two. Unfortunately finding period picture of these machines on river vessels has proved to be more difficult than I expected, possibly because of their more extensive cabins and enclosed decks. At the same time it is useful to remember that we do not have a single confirmed photograph of a Red Boat. Given their popularity and social importance this is really surprising. Yet it is also a valuable reminder of exactly how spotty the historical record of popular culture can be.

While we lack actual images of the machines in question, Barbara Ward’s reconstruction do suggest that each Red Boat came outfitted with a number of windlasses. One of the really interesting things about the Red Boats is that the entire fleet used by the Guangdong opera guild was built to identical specifications. Further, every specific cabin location in any ship shared the same name. As a result any opera company could set foot on every ship and be instantly at home. These vessels were designed to be perfectly interchangeable.

The names of the various cabins occupied by the performers are often quite evocative with the very best cabins being given soaring titles (‘The Prince’s Palace’). Less desirable spots tended to carry distressingly literal names (‘Rubbish Dump’ or ‘Mosquito Den’). One of these less preferred cabins was referred to as “hoist sales place,” and Ward’s plans of the vessels indicate that it sat by (or on top of) one of the windlasses used in conjunction with the ships retractable mast.

Conclusion

Wing Chun students occasionally point to the image at the top of this post as an example of a wooden dummy being used on one of the Red Boats of the Cantonese opera. Indeed, the ship in question does appear to be some sort of river barge, and the martial artist’s actions look like modern dummy usage. Unfortunately I have never been able to confirm the actual province of that particular photograph (though I have now heard a number of theories on its origin). But in more technical terms, what is this actually a picture of?

After my conversation with Dr. Van Tilberg and a little research I think that we can be fairly certain that the “dummy” in question is actually a windlass of the type that was used as deck machinery on Chinese vessels in the Late Imperial and Republic periods. To do work such a device would have to be mounted horizontally, but in this case it has either been mounted vertically, or possibly just propped upright. The fact that the individuals in question are using it to demonstrate what appears to be movements from a dummy form suggests that they also noted a correspondence between this particular bit of naval machinery and the sort of training tools that would later become common in Wing Chun.

I remain skeptical that very many sailors had something like this permanently installed on the decks of their ships. All of the photographs I have seen indicate that the decks of smaller vessels were pretty busy and complicated places, and such machines would have been more useful for doing actual work. Nor did Ward find any evidence of ship board dummies in her investigating of life on the Red Boats (though admittedly that was not the focus of her work).

Still, boats were a ubiquitous part of life in Southern China. All sorts of individuals traveled on these vessels to visit other villages or conduct mundane business. Given the constant use that machinery like this endured, one suspects that there must have been a small army of carpenters who made their living rebuilding and repairing these windlasses. We may never know if the origins of the modern Mook Yan Jong can be found in a spare windlass propped up on a deck (as in the opening image), or in the creativity of an individual boxing master re-purposing or commissioning a custom model from a local carpenter. Yet it is an important possibility to consider.

Of course there are other possibilities. While we are on the topic of machinery there are some other devices that one might want to take into account. Chinese engineers developed all sorts of simple machines for moving water, and nowhere was this technology more vital than in the shifting sands and flooded rice fields of the Pearl River Delta. One such device can be seen above. Again, note the arrangement of multiple spokes of “arms” along a circular trunk. Any farmer would have been familiar with similar devices used to raise water into elevated rice patties. Indeed, it is not possible to rule out these sorts of machines as another source of inspiration for the wooden dummy.

Still, the naval windlass seems to have a number of correspondences that are hard to ignore. These can be seen in the size and the shape of the trunk, the need for easily detachable arms and even the sorts of hole configurations that were commonly encountered. Clearly the Mook Yan Jong has undergone an extensive evolution and specialization to become the training tool that we know today. Yet the iconic Wing Chun’s dummy may be a tangible link to southern Chinese culture’s nautical past.

oOo

If you enjoyed this post you might also want to read: The 19th Century Hudiedao (Butterfly Sword) on Land and Sea

oOo

July 3, 2015 at 10:58 am

Fut Gar and other southern (village) styles use a 3 arm dummy with a different configuration than the wing chun dummy. As well, conditioning exercises on a post or tree is favored by the military in the early part of the 20th century (and currently in some units). Perhaps there is a commonality among these practices that does not have its origin in the red boats?

July 3, 2015 at 9:28 pm

Great post. I can imagine an old martial artist, back in the day, training on some farm equipment or etc, which later developed into a dummy. It is a very thought provoking post. I’m sure these guys were quite ingenious in what they used to train. Even today you see students practicing their kung-fu on almost any object they encounter. If you were a kung-fu master (or student) with limited resources you would likely turn anything into a training device.

I would like to comment on one thing – some lineages of Wing Chun which claim to come directly from the red boats actually used the bamboo rings as their “dummy”, not the traditional dummy. As a matter of fact, that is one of the common traits I’ve seen in those lineages. The explanation was that with the bamboo rings the training could be done anywhere, anytime sitting or standing and in small spaces, etc. I had never heard of the wooden dummy being present on the opera boats at all until you mentioned it here.