Introduction: Sun Lutang at the Crossroads of Modernity

In the first section of our special series on Sun Lutang we presented an outline of the life and career of a key figure in Chinese martial studies. Sun has made many contributions to the traditional martial arts community. He is responsible for innovations as diverse as the use of photography in training manuals, the popularization of the term Neijia (or internal) as a descriptive category, the pronounced emphasis on health and philosophy in the Chinese martial arts, and the creation of his own style of Taiji. His ideas have been incredibly important. For better or worse they have shaped the subsequent development of the martial arts in every region of China and the west. We will look at this legacy in more detail in the next post.

From the perspective of Chinese martial studies, perhaps the greatest gift that Sun left was a rich and well documented life that intersected with some of the most important social, political and martial trends of the era. Even though Sun’s detailed diary of daily life was lost in the Cultural Revolution, we still have a surprising amount of information about his life, study, travels and thoughts on the state of the martial arts. He associated with many of the leading lights of the period and witnessed critical events in the formation of the social systems that we now refer to as the “traditional martial arts.”

Sun Lutang’s life provides students of Chinese martial studies with a surprisingly clear window into the past. By carefully studying his associations and innovations it is possible to gain a much greater understanding about how the martial arts of northern China were evolving and changing at the end of the 19th century. His biography, when placed in the proper context, reads like a textbook of martial arts history.

The following post goes back and reviews a couple of trends that first arose in our brief summary of Sun’s life and career. Our goal is to ask how these events illustrate larger themes or questions in Chinese martial history. No shocking revelations emerge from this exercise. Yet a much more nuanced view of the basic institutions of Chinese martial culture emerges when they can be studied within the career of a single martial artist.

Closed Doors vs. Secure Networks: The Economics and Social Functionality of Traditional Instruction.

We have all encountered the debates before. Who was a “closed door” student of whom? Who can really claim to be a true inheritor of some style of Kung Fu? Of all of the criticisms that one can make of the Chinese martial arts, a lack of interest in politics will never be one of them. At the end of the day all sorts of debates in the modern Chinese martial arts seem to devolve into attempts to criticize or illegitimate the quality of someone else’s instruction.

The idea of “secrecy” has infected the Chinese martial arts like a virus. It seems that everything that emerges out of this cultural milieu continues of have issues with secrecy. Even in my own art, where Ip Man loudly and explicitly rejected the idea of “secrets techniques” and “closed door” teachings, there are still vigorous debates as to which of his students was his super–secret “closed-door disciple.” The answer of course is that none of them were. Yet the idea of secrecy is so deeply embedded in the culture and the mythology of the martial arts that it is hard to exorcise. After all, we all know that this is how the arts were originally taught. Right?

Well, not quite. It is true that the modern institution of the public commercial school is a fairly recent invention. To have public commercial schools a few things need to be in place first. You need to have a monetized economy where people have jobs that afford them free time and pay them a cash salary that they can pass along to their teachers. The creation of lots of cheap, easily available, commercial real estate also helps this process along.

In short, our current martial arts institutions are an outgrowth of modern capitalism. They are a natural extension of our social and economic world. However, early 19th century China was not really a “capitalist” place according to our current understanding of the term. For the most part the economy was not monetized. Except for a small group of very wealthy individuals, most people rarely had access to cash. The Qing government didn’t even bother to consistently mint coins as they accepted tax payments in raw one ounce silver ingots or Mexican silver dollars. In short, while there may have been groups of people who wanted to learn the martial arts, there usually was not a really easy way to pay the teacher.

Payment often happened “in kind.” One paid a teacher by inviting them to live with you, providing them with rice, new shoes, and new clothing. While effective, this situation is not very economically efficient. It is hard for a martial arts teacher to monetize the value of his knowledge or skill with “in kind” payments. As a result many of the best martial artists would simply work for the military or an escort company (some of the few places where you could earn a regular salary) and not teach at all. Teaching was often seen as a “retirement job.”

The best teachers were usually supported by a single family. A father might hire a teacher, who lived as part of the household, to teach his sons. This might be seen as a means of preparing them to take the government’s military service exam. Obviously this sort of instruction was private. But was it really “secret”?

The answer is no. It many have been a source a jealousy, and certain ideas were exclusively held, but the teaching was not “secret.” If you had enough money to support and house a full-time teacher, you too could know the martial secrets of the universe. This was a system characterized by inefficiency, but it was not driven by secrecy. After all, these teachers were looking for a way to support themselves. Too much secrecy would work against their basic economic goals.

Occasionally other teachers were able to find a way around this dilemma. In theory it would be possible for a group of students to support a teacher just as easily (or more easily) than a single family could. In practice this was usually a challenge, especially when dealing with impoverished peasants.

While everyone would want to enjoy the benefits of the teaching, when it came time to pay their fair share, a lot people would come up short. This is the basic idea behind the “free rider” problem in economics. Cooperation is rare in large groups because individuals do not directly bear the costs of defection and enforcement is difficult. I have long suspected that many of the strongly community/family oriented norms seen in traditional martial arts schools (where a Sifu is treated, in some ways, as a father) were a partial attempt to solve the free rider problem. But that is a subject for a different post.

What you do see in northern China in the 18th and increasingly in the 19th century are traveling martial arts teachers. They would have a circuit and would go from one village festival to the next. Festivals often corresponded with the selling of crops so these were rare times when peasants had disposable income.

Such individuals would set up outdoor boxing grounds, give demonstrations, sell medicine, and (if they were better known) recruit students and hold classes. This sort of rural instruction at outdoor boxing grounds is precisely how some of the most important styles in Northern Chinese hand combat, such as Hong Quan and Plum Blossom Boxing, were spread. Esherick has even written short biographies on a number of these sorts of instructors which can be found in his volume on the Boxer Uprising.

In fact, it is in a setting exactly like this where Sun Lutang first encounters Master Wu teaching a group of local peasants the finer points of Shaolin boxing. Wu’s life history is very instructive. Like Sun he grew up hard and traveled extensively. Given his location and era, his claim to have studied at Shaolin is actually pretty plausible. His martial repertoire, which included Hong Quan, 64 Hands Free Fighting, and “Virgin Boy” Qigong (among other forms), would have fit right in at the venerable temple. More interesting was the fact that Wu was a veteran of the terrible Taiping Rebellion, the largest and most destructive civil war in all of human history. After the end of that conflict he made a living as a public performer, traveling from market to market.

The ease with which Wu accepted Sun as a student is interesting. Sun had to petition for acceptance, but it is clear he had nothing of value to offer his teacher. In short, Wu (70 years old at the time) made his living teaching the martial arts in a “traditional” setting, yet he was probably teaching all comers, even penniless youths like Sun.

A different model of martial arts instruction can be seen after Sun arrives in Baoding. Here he is introduced to his twin mentors, Zhang and Li Kui Yuan. Li was a student of Xingyi and became Sun Lutang’s second hand combat teacher. This is interesting as it appears that Li did not teach a large number of people. Why? Because he had a more effective means of monetizing his skill. He was the owner of a successful armed escort service.

This career path was probably not open to Wu for a variety of social reasons. In order to be allowed to operate in public spaces (like markets), armed escorts had to have the trust of local officials. Li was a known quantity and his social network included scholars, like Zhang. It was precisely these contacts with social elites that allowed him to make a living. It probably was not necessary for him to teach to support himself.

But sometimes individuals teach for other reasons. A friend of mine in Chengdu has been interviewing local martial arts masters. One of the interesting (and sad) things that emerged from these interviews is that with the current contraction of interest in the martial arts, there are not enough students to go around. There are a lot of individuals with a lifetime of skills who wish to pass something on, but they just can’t find anyone who is interested in learning. It seems that teachers need students as much as students need teachers. At its most basic level what we are discussing is a profoundly human relationship.

When you look at the amount of effort that Li invested in Sun, apparently only because the boy showed an interest in the material, I start to suspect that this is not the first generation with a deficit of students. Studying the martial arts was not a socially prestigious activity in the 19th century, especially not in the social circles that Li moved in while in Baoding. Like the old Chinese proverb states, finding the right student can be just as difficult as finding the right teacher. In fact, many of the accounts of late 19th century China that I have reviewed would seem to indicate that it was actually a “buyer’s market.”

Sun was eventually adopted by Li as his formal disciple. Lacking a father, I suspect that this ceremony had deep resonances for him that went well beyond their martial significance. It does not appear however that Sun was a “closed door” student of Li in the more esoteric sense of the word that is common today. This term has been invested with all sorts of exotic meaning in countless martial arts novels, radio programs and movies. Its original meaning was actually more mundane. Such a student lived full time with the teacher, often taking care of household chores and helping to maintain the school, so that they could dedicate themselves to full-time study.

Living with your teacher gives one an opportunity to observe their practice and martial philosophy in detail. Often those aspiring to a martial career of their own might live with their teacher, though this was not always the case. Sun appears to have continued to work for his Uncle (who, unlike his first employer, was kind and actually paid him) during this period. Yet there is no indication that Li purposefully held back information simply because Sun had not yet been taken on as either a formal disciple or a “closed door” student. In fact he indicated very strongly that he taught the young boy everything he knew and even introduced him to his teacher to continue his formal education.

This brings us to the next stage of our observation. In popular discussions the institutions of traditional martial arts instruction are always viewed as primarily an engine of secrecy. Their great virtue in the eyes of the movie going public seems to be their perennial exclusion of “outsiders.” But when you look at Sun’s life as it has been outlined in my previous post, it is clear that this view doesn’t really capture the true essence of how these institutions functioned in a real social setting.

Rather than being purely about exclusion, the traditional modes of education created artificial hierarchies meant to entice people to join. These hierarchies gave individuals a chance to build social status that they might not otherwise have. That promise of social status was in turn a means of attracting students (like Sun) who might otherwise have spent their time developing other talents. It was the “myth” of secrecy and exclusion that made the promise of inclusion and status so attractive.

When looking at late 19th century martial arts history it is vital to understand this powerful psychological dynamic. At the same time, it is probably better not to believe all of the propaganda. It does not actually appear that many people were ever turned away from martial arts instruction for any reason other than a lack of money, and in some cases (like Sun) even that could be overlooked. We must not confuse this “veneer of exclusivity” for real elitism. It seems that most martial arts teachers benefited from the former but could not actually afford the latter.

Promoting the Chinese Martial Arts: From Networks to Public Institutions.

The traditional modes of instruction did more than just create artificial power structures for the achievement of social status. They also became powerful networking systems. As one might expect, the dominant metaphor used to define and understand these networks was the traditional Chinese kinship system. This gave one an immediate frame of reference to understand ones social relationships with other practitioners of the same style who you may have never met before.

These networks of social relationships were very important to the people that constructed them. Workers in Guangdong in the late 19th century used them to network and find out about employment opportunities. I am sure that individuals in Northern China did exactly the same sorts of things.

These networks also became an infrastructure that could facilitate the transfer of martial knowledge. They were a means by which one could branch out, travel and get introductions to study with different teachers. Rather than being exclusively about secrecy, traditional martial structures actually provided students with access to a vast network of information and contacts.

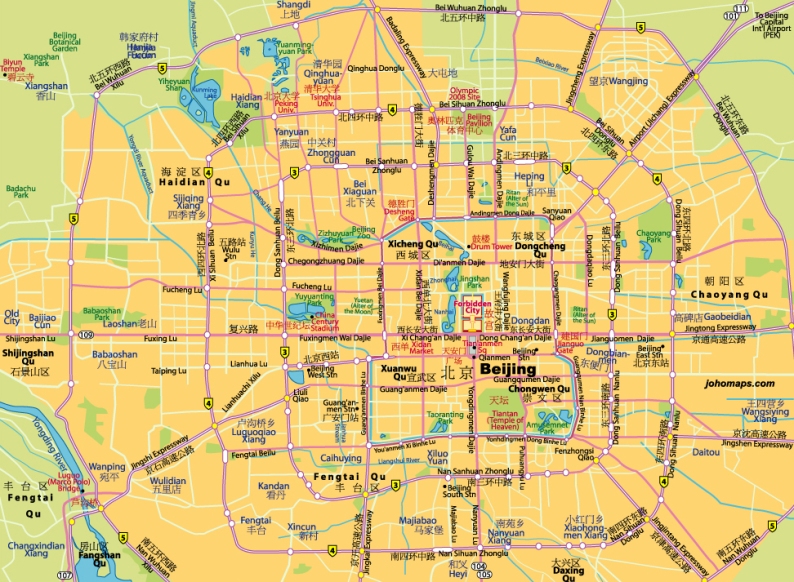

The average martial artist, intent on getting a job and making a living, probably did not do much to exploit these opportunities. Sun Lutang’s life as a young adult is fascinating precisely because he did call on the full resources of his martial network. Not only did he exploit direct lineage relationships (traveling to Beijing to study Xingyi Quan with Guo Yun Shen for eight years), he drew on other types of friendships and alliances as well. From Guo he received a letter of introduction recommending him to Cheng Ting Hua, an important Bagua instructor. He subsequently studied with Cheng for another three years. In short, a detailed examination of Sun’s studies can teach us much about the actual social structures of 19th century martial arts communities.

His frequent travels make it clear that Sun had a degree of flexibility in his life that not all martial artists of the period were as lucky to possess. But it is also clear that an overriding ethic of “secrecy” was not the thing holding them back. Rather than seeing traditional martial arts kinship systems as “engines of exclusion,” they are better viewed as secure social networks, in an otherwise dangerous environment. The very purpose of these networks was to build social status and make the open sharing of information possible.

This is a critical point as social reformers after the Boxer Uprising would spend a lot of time criticizing the traditional martial arts community for its fratricidal and superstitious secrecy. There were very few protests from the traditional martial arts community over these demands for reform. They certainly realized the value of exchange and discussion and they saw their institutions as something that accomplished those goals.

Given the quasi-feudal economy that existed at the start of the 19th century, these traditional teaching structures might have been the most efficient institutions possible. However, the basis of Chinese economic life was being rapidly reformed. This made new types of cooperation, sharing and networking possible. Ever the innovator, Sun would be at the forefront of these reforms.

I think that we need to look to early 20th century “Swordsman” novels, and later Kung Fu movies, to understand the emergence of our current ideas about traditional martial arts networks. These stories often revolved around deadly rivalries between schools and the theft of an ultra-secret text that revealed the true heart of Kung Fu.

Apparently someone did steal a book from Sun Lutang. It was his daily diary, taken by a live-in student. While I am sure there was a lot of interesting information about the day to day life of the master in that volume, I doubt there was any hidden wisdom. Instead what the wayward student likely discovered was a painstaking record of exactly how many hours his teacher had dedicated to practice and hard work.

I have noted in another post the interesting observation that Chinese martial arts students from the 1960s-1980s were often actually much more “conservative” in their understanding of “martial virtue” than their teachers. The life experience of individuals like Sun Lutang, T. T. Liang or Ip Man were shaped by tremendously tragic events and vast military conflicts. Having seen quite a bit of real conflict in their lives I think that these individuals knew exactly what the martial arts were, and none of them were too attached to traditional institutions. Rather their loyalty lay with the goals that those institutions were meant to accomplish. When times changed they simply created new teaching structures.

It seems that later generations of hand combat students, more concerned with identity formation than survival, came to see “traditionalism” as a goal in itself. This is a very different attitude than what we see exhibited in the lives of most of the early 20th century martial arts masters. While some of these individuals may have been socially conservative, as a group they are better characterized by their pragmatism.

Again, we see this in the life of Sun Lutang. Even though he was trained on a traditional “boxing ground” in the 1870s, by the 1910s he is running large modern commercial schools with hundreds of students around Hebei province. Apparently he continued to accept these students with the traditional rituals, but there can be no doubt that the institutions they were educated in were quite distinct from what he had grown up with a generation before.

Reforming the Chinese Martial Arts to Save the Nation

When examining the middle and later period of Sun’s life we should also note the development of a new sort of martial arts institution. The rituals and practices of a traditional “lineage” education were quickly adapted by commercial public schools in the 1910s and 1920s. This process of consolidation and evolution was made possible by the increased monetization of the economy. It was also driven by the growing emphasis on training better educated urban workers and professionals. These individuals had money, but they also had demanding day jobs. Classes had to be restructured so that information could be conveyed within a 1 hour class period. Further, these classes had to be offered either before of after the close of the working day, or sometimes during the lunch hour. In short, the martial arts had to be remade to fit around a typical industrial work schedule. Again, we see a veneer of “traditional exclusivity” being placed around what is actually a quintessentially modern public institution.

But that veneer of secrecy was not always good marketing. In some situations it was necessary to publicly demonstrate one’s dedication to the nation, modernization and revolutionary goals. As a result an entirely new set of non-lineage based cooperative institutions begin to emerge in the urban areas of China between about 1910 and 1928 (when the spread the of Guoshu movement finally collapsed this section of civil society).

The hallmark of these groups was a call for “national salvation” through martial arts education. Typically such groups combined the efforts of teachers from a number of different styles. They publicized the martial arts, called for reform (usually by ending the twin perils of “secrecy” and “superstition”) and published lots of newspaper and magazine articles on how hand combat training was compatible with “modern life.” Of course they also offered classes, often at very reasonable rates, to both the public and local schools.

Jingwu was the first of these groups to really explode on the national scene, but it was far from alone in the field. It seems that every city of any size had at least a few of these modern martial arts federations. A classic example might be the Tianjin China Warrior Society (based in Tianjin) which did much to popularize and spread Xingyi Quan throughout Hebei and actually published a few of Sun’s books. The network that formed around the “Yi” schools (later the Zhongyi Association) in Foshan is another example.

The Beijing Sports Lecture Hall, which Sun joined in 1915 or 1916, was a similar institution. It taught multiple styles of Taiji and a few other martial arts to the local citizens of Beijing. Sun saw his involvement with the group as a way to save the Chinese martial arts, strengthen the people of the country, and contribute to the welfare of the Chinese nation. These grandiose sounding goals were very common. They are not all that different from what a member of the Jingwu Association or the Tianjin Chinese Warrior Society might have claimed.

An interesting question to ask is why this sudden interest in patriotic community building emerged within the Chinese martial arts community in the first place. Clearly some of the later groups were formed as a response to the initial success of Jingwu and the other early pioneers. But there was a lot of activity in this area around 1910, well before most people in the Chinese martial arts community would have had any opportunity to hear about Jingwu.

I suspect that there are three related issues that can account for this sudden burst of institution building and reformist zeal. To begin with, the Chinese martial arts were in genuine peril after the 1900 Boxer Uprising. Not only was civilian hand combat briefly suppressed by the state, but it became deeply unfashionable. This was something of an accomplishment given that it had never been that popular in the first place.

The Boxer Uprising was an embarrassment to the nation and it led to renewed calls for modernization. This happened in the military realm in 1905 when the Qing abolished the Military Service Exam. Training students to take that exam had been one of the main professional callings of martial arts teachers throughout China. Many people trained in the martial arts explicitly because they wanted a career in the military. That career path was, with some exceptions, closed to martial artists after 1905.

In short, the Chinese martial arts took two critical hits in a five year period. Lots of hand combat teachers found themselves unemployed at exactly the same time that their skills are being publicly ridiculed and blamed for the weak state of the nation.

This is the environment that fueled the burst of social organization that took place over the next decade. Social elites were paying more attention to physical culture as they looked at reforming the national education system and military, but the traditional martial arts were being shut out. In order to save their arts, and position in society, hand combat teachers began to organize in an attempt to prove their revolutionary credentials and demonstrate the benefits of martial arts training to a modern state. And the Japanese system of “Budo” just to the east was a powerful argument that this could be done.

I think that this is the main reason why these groups were so desperate to get government backing in the first place. Most martial artists had worked for the government (specifically the military), right up until 1905. Jingwu may have been somewhat unique in its steadfast dedication to civil society. I suspect that most of these groups were actually more interested in renewed government patronage, and were only too happy to be incorporated into the government run Guoshu network after 1928. Still, the evolution of the martial arts in the 1910s and 1920s was shaped in important ways by large, non-lineage based, public institutions. It is important to understand where they came from and how they functioned.

Conclusion

Some individuals dedicated their entire lives to these institutions. It is clear that Sun did not. He taught at the Beijing Sports Lecture Hall, and even offered classes on Chinese philosophy there in an attempt to attract more educated, professional students. But it appears that Sun also accepted other official appointments and teaching responsibilities during this time. He also taught a huge number of students in his private “lineage” schools.

His elite networking and role as a leading public intellectual of the martial arts were both critical activities during the 1920s. Friends in high places could open many doors. For instance, the widespread adoption of martial arts training as part of the secondary school physical education curriculum throughout the nation was due in no small part to countless friendships cultivated between local martial artists and provincial officials.

Secondly, as more educated people became interested in the martial arts there was an increased demand for a new type of literature. While swordsmen novels remained popular, students now wanted more practical information. This demand was driven by the vastly increased number of urban consumers with buying power who began to study the martial arts during this period. The efforts of Sun and other to change the social profile of the martial arts led directly to the explosion of the Republican era martial arts manuals discussed by Kennedy and Guo.

Contrary to their off-handed assertion, small mass-produced boxing manuals or chapbooks had existed in the late Qing period. I hope to discuss a translation of one such source in a coming post. But there is no doubt that printed martial arts manuals became vastly more common as number of educated middle-class martial artists exploded.

Sun’s five books were some of the most important works on the martial arts published in this period. In fact, I think it is safe to assert that his lasting impact on the Chinese fighting arts came through his publications. In lineage terms, he was never quite as successful as some of the other top martial artists of the period (usually named Yang), and so he does not get quite the same respect in China that one might expect given his actual contributions.

Still, his ideas have lived on and are incredibly important. They have been disseminated through countless reprints of his books (now firmly in the public domain) and through the lectures and discussions of many other martial artists who may, or may not, remember to properly cite their original source material. Anytime you go to a Taiji class and hear inscrutable conversations about what someone is doing to their “qi,” they are (usually unconsciously) repeating something that Sun said almost 100 years ago. The current fashion of martial arts, Daosim and qigong based health practices that many of us now take for granted would not exist without Sun’s books.

Sun’s career is remarkable because he was both part of the general movement to modernize the martial arts, making them accessible to educated individuals, but unlike most of his contemporaries, he could actually give those middle-class minds something to wrestle with. I think that, more than anything else, explains his lasting influence on the Chinese martial arts.

In the final installment of this series we will take a closer look at the origins and after life of some of Sun’s key ideas. Why did he believe that the Chinese martial arts were intrinsically linked to Daoism? What exactly did he mean by “internal”? In what ways are these ideas still shaping the martial arts today?

Click Here For the Third Section of our Three Part Series on the Life and Influence of Sun Lutang.

Leave a comment