***Its Labor Day in the United States and I am currently off on a fieldwork trip. As such this seems like a great time to revisit a post from earlier this year on the importance of guilds and labor unions in the Chinese martial arts, a critical and too often overlooked subject. Enjoy!***

National boxing is very popular in Fatshan city. It is reported that there are some eight national boxing schools which are directed by well-known national boxers. School fees are only from two to three dollars a month.

“General News,” Canton Times, September 9th, 1919 (page 7)

Foshan would have been a fascinating place in the late 1910s. The Hung Sing Association’s brand of Choy Li Fut dominated much of Guangdong’s martial arts scene. Interesting and innovative things were happening in the Hung Gar community. And of course Ng Chung So was cultivating a small but dedicated community of Wing Chun students on the eve of a period of rapid growth that would unfold in the 1920s and 1930s. This brief notice informed English language readers in Hong Kong and Guangzhou of something that we already know. The Southern Chinese martial arts were about to enter a brief, but brilliant, golden age.

What was the social position of these practices, and how can we best explain their flowering? Popular theories on both questions abound. We hear tales of a Southern Shaolin Temple, wandering revolutionaries and secret societies galore. In more academic works we encounter the Jingwu Association’s sophisticated, nation wide, advertising campaigns, or the attempts of government officers and educational reformers to create a new martial art for the new Chinese nation.

It is easy to pit these two schools against each other and assume that this is the totality of the debate. If the mythological explanations are wrong than the elite driven national narratives must be correct. What is more confusing is that there are elements of truth on both sides.

While it is clear that the Qing never inspired southern kung fu by burning an actual temple full of real Shaolin monks, that image gripped the public imagination and allowed countless local styles to wrap themselves in the banner of Republic era nationalism and revolution. This facilitated the localization of abstract notions like “the nation,” and provided a pathway for individuals to enact and experience a new imagined community on an embodied level. Likewise, the Jingwu Association advertised a middle class art that was both socially progressive and compatible with the demands of modernity. They provided a ready made pathway for those who wished to argue that the Chinese martial arts should serve as the foundation for modern Chinese society. Indeed, we are still feeling the effects of their reforms.

Yet both of these explanations tend to neglect the actual experience of most of Southern China’s martial artists. Wuxia novels were written in a high literary style and tended to be more of an elite past time. Likewise, while the urban middle class that Jingwu appealed to was growing in relative terms, it was still a very small proportion of Southern China’s total population. Most urban citizens were common laborers or domestic help. They couldn’t afford Jingwu’s dues and likely had little interest in the global, cosmopolitan, vision that it promoted.

To understand the rapid growth of the martial arts in Southern China, one should start by investigating local labor markets. More specifically, we need to focus our attention on the relationship between the region’s many small labor unions and the massive proliferation of urban martial arts schools in the Republican period. These are issues that Jon Nielson and I already examined in our book, The Creation of Wing Chun: A Social History of the Southern Chinese Martial Arts, but perhaps a more focused discussion is in order.

Consider again the news clipping at the top of this essay. It actually makes a great deal of sense that Foshan would have led the way towards the professionalization of the martial arts marketplace in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Its position in the regional trade system made it a unique manufacturing powerhouse. The city was famous for its commercial porcelain exports and it enjoyed a monopoly on the regional production of iron goods. Silk and sugar were also regionally important trade goods. And its streets were filled with workshops making the household goods that supported Guangzhou to the East. Indeed, much of what was sold in Guangzhou was first manufactured in the workshops of Foshan. The “industrial revolution” (and I am using that term very loosely here as most of this production actually happened in small shops), came early to Foshan.

All of this had a critical impact on the development of local labor markets. In an era when most peasants in the countryside rarely had much cash on hand (inhibiting their ability to buy luxury items), workers in Foshan were paid a steady wage. They worked predictable hours. More importantly, they were organized into collective trade guilds. In addition to negotiating working conditions, these groups were responsible for providing certain goods to their members, such as housing, shared worship spaces (sometimes a cemetery) and even entertainment. During the final decades of the Qing dynasty it became increasingly popular for guilds to use their pooled economic resources to hire martial arts instructors. And given the region’s occasional bouts with labor unrest, it is hard not to see that as a recreational choice with social implications.

This process continued and accelerated as later industrialization swelled cities like Guangzhou, Shanghai and Hong Kong with peasants leaving the countryside looking for (relatively) well-paid work. While patterns of guild organization gave way to small labor unions, these still functioned as something of a social safety net, providing housing assistance, entertainment and networking opportunities. Lin Boyan (1996) has described how displaced workers from the countryside would pool their resources to hire a local martial arts teacher, bringing them to the big city. This was a world that was at once familiar, but still quite different from, the era of small town militias and public boxing grounds that had come before. Note the following observations on the Guangzhou’s changing cityscape as reported in the North China Herald.

CANTON’S AMUSEMENTS

_________

More Time Now for Play

_________

From Our Own Correspondent.

Canton, Sept. 5.

The Cantonese are giving more time to amusement, or as a matter of fact they have more time to play. The civil servants and railroad employees in the city, who have regular office hours, have adopted tennis as their popular form of recreation. The Sun Ting Club, an organization of returned students and younger officials and leading merchants of the city, has a baseball team of more than 20 regular members. The Y.M.C.A. gymnasium and swimming pool are attracting a large number of business and professional men daily, and the law court and department store clerks enjoy their games alike in these places.

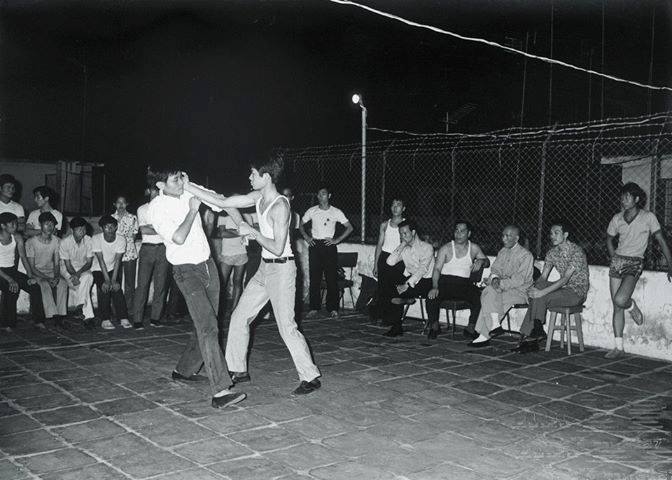

The laboring class now has more time for amusement and play since the success of its demands for shorter hours and higher wages through a series of strikes. Its members usually organize themselves into clubs for physical training, usually boxing,—now under the title of “national art of self-defense.” These clubs also teach the Cantonese popular amusement of lion dance, displaying their skill at parades or other public appearances.

The moving picture shows are now an institution in Canton, and there are half a dozen theatrical [opera] companies here wholly composed of young women and girls. Nowadays the country towns and villages have no difficulty in getting support for a show to come to their towns for a season from two to four days at a time with four or five shows in a couple of months. In Canton the show places have to close at midnight, while in the country districts one may last from eight o’clock in the evening to five in the morning. In addition to the regular theaters, the large department stores and amusement parks provide a variety of shows for which a general admission fee is charged, and many spend their leisure hours there.

“Canton’s Amusements: More Time Now For Play,” The North China Herald. September 17, 1921.

Once again, the advent of limited work hours and greater pay (the fruits of hard fought battles with business owners), opened the doors for an explosion of kung fu schools. Again, all of this happening in the middle of the Jingwu era, but that organization’s progressive reforms and nationalist agenda do not seem to have much to do with the trends reported in these articles. And while Jingwu would vanish (except in South East Asia) between the 1920s and the 1950s, the sorts of folk kung fu styles favored by these labor unions (Hung Gar, Southern Mantis, Choy Li Fut, Wing Chun) are still very much the backbone on the modern kung fu community.

Still, as this newspaper account makes clear, the popularity of these styles did not emerge in a cultural vacuum. These practices were consumed by the same workers who enjoyed the growth of opera (indeed, the “Red Boats” were still a common sight in the 1920s) and cinema. The social meaning and identity of these practices sat in juxtaposition to pursuits like tennis or swimming, activities that were far more popular among China’s upper middle class mangers. Still, both kung fu and western athletics benefited from the same expansion of the region’s leisure economy.

This is not to say that the social implications of joining a kung fu school were identical to signing up for a baseball team. There was often an undercurrent of social power (perhaps even coercion) in the former that was not evident in the latter. Workers certainly enjoyed martial arts practice, yet many of these schools were sponsored by “Yellow Unions” which included the company’s officers within their membership. In that case one’s employer might gain additional social leverage over workers by also having a leadership role within the martial arts community. And martial arts teachers were even hired to help firms “deal with” labor issues.

Boxing was also seen as an important mechanism for militarizing the labor movement by members of the KMT and other social reformers. Promoting this sort of martial arts training seems to have been regarded as a extension of party’s more revolutionary and anti-imperialist goals. (One could discuss the clear thematic connections to the newly resurgent mythos of the burning of the Shaolin Temple here, but that will need to wait for some future post).

Nor was this militarization of the labor force merely theoretical. Jon Nielson and I discussed the impact of the 1925 boycott of British goods (and trade with Hong Kong) in our previous volume. Multiple martial arts instructors and organizations were involved in that effort. Yet the following report from the China Press notes that by the second year of the strike such training had become mandatory for the workers on the picket-line and in Guangzhou.

By suggestion of the Kuomintang Workers Delegate Conference, comprising more than 170 labor unions in Canton City alone, for members not joining the picket regiment which will be trained under military system, all labor unions quartered in Canton will conduct classes of boxing. It may be recalled that this conference has decided to organize a picket group of 1,700 to 2,000 strong.

“All Foreigners At Canton Under Police Surveillance.” The China Press. September 23, 1926. P. 7.

Still, it was not all revolution and “charging the barricades.” The promotion of martial arts within labor unions also seems to have been part of the government’s larger efforts to promote physical culture. We already discussed Chu Minyi’s efforts to create upscale martial arts clubs for public sector employees. Those efforts did not occur in isolation. Rather they were an extension of trends that had been going on for some time. Once again, we can turn to the China Press for another news clipping that nicely fuses labor relations, martial arts instruction, and the promotion of a national physical culture movement, this time from 1933 (the height of the Guoshu era). Again, these are the stories that we ignore when we focus exclusively on a handful of elite social movements.

Labor Unions Due to Battle in Athletic Contest Next Spring

For the first Time in local Chinese athletic history, an All-Shanghai Labor Track and Field Meet will be held at the Public Recreation Ground, Nantao, next spring. Four open Championships will be staged. They include track, field, all games and Chinese boxing. Each labor union is required to participate in at least one of the four championships games.

The China Press. December 16, 1933 page 6.

Conclusion

All of this would be stripped away by the victory of the Communist Party in 1949. Its important to note that they never explicitly banned martial arts practice. Indeed, the newly reconstituted wushu sector was promoted and cultivated within the sports and educational realms. Many of China’s most famous remaining martial artists found new homes as coaches at universities or teaching Qigong and Taijiquan classes in hospitals.

But that sort of elite practice excluded most of the nation’s population. As the Party transformed the economy, nationalized markets and banned labor unions, more plebeian martial artists no longer had the incentive or opportunity to continue to practice. By the end of the 1950s much of the martial arts culture that had dominated the Republic era simply vanished on its own.

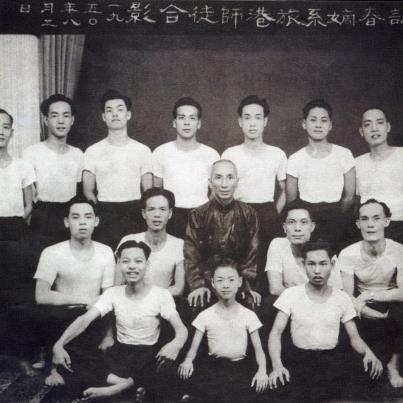

Things were different outside of China. Small labor unions continued to sponsor martial arts classes in South East Asia and Hong Kong. Wing Chun students can all recite by heart how Ip Man began his teaching career at the Restaurant Worker’s Union headquarters in Hong Kong. Nor was this the last labor group he would teach during the course of his Hong Kong career. In light of the foregoing discussion it should be clear that this is not an incidental element of the story, or a bit of local color. It reminds us of the historic importance of Southern China’s guilds and labor unions as engines of working class martial arts practice. During the Republic period they promoted and shaped popular kung fu traditions. In the early 1950s one union in Hong Kong gave Ip Man a leg up, ensuring Wing Chun’s survival and eventual spread throughout the global system.

oOo

If you enjoyed this you might also want to read: Lives of Chinese Martial Artists (3): Chan Wah Shun and the Creation of Wing Chun.

oOo

June 29, 2018 at 5:45 pm

Don’t know how accurate or where you got the part of Red China not banning Kung Fu in China. My master and two cousins who came out of Toisan village said kung fu was banned. Any “Hard” styles had to be taught secretly and masters only accepted students from someone they knew very very well. Many masters caught continuing teaching were beaten, imprisoned or killed….so the ones able to escape escaped.

The communist govt’ know from history that most revolts are lead by kung fu practitioners, clubs or societies so they banned them, but they know some people were still practicing secretly so decades later they allowed a new watered down martial arts to appear and called it WuShu. Legitimize it and give it a lot of recognition and lavish practitioners with awards and medals and made it a “National” sport.

Anyways, that’s what the “Old school” masters’ version of this part of China’s history…the ones who made it out alive.

June 29, 2018 at 7:25 pm

Obviously this is an account that we hear a lot. And I am certainly not going to say that it is incorrect. I can come up with a couple of pretty good horror stories out of my own lineage as well. But I worry that as these stories are passed on in the West they take a very complex subject (the state’s evolving relationship with the martial arts over the course of decades) and reduce it all down to a couple of sentences. If you begin to break it down year by year it becomes clear that the early 1950s was different from the late 1960s, which was again vastly different from the late 1970s. And how your were positioned within the state and society seemed to make a lot of difference as to how well a martial artist was able to adapt or survive the cultural revolution (which we have seen in biographies of the martial artists profiled on this webpage).

If you are interested in chasing this history down further (and honestly, I am surprised that there is not more interest in doing detailed studies of this period as its very important) you might want to start by checking out this article by one of the guest author’s on the blog:

Daniel M. Amos. 1995. “THE RE-EMERGENCE OF VOLUNTARY ASSOCIATIONS IN CANTON, CHINA.” Asian Perspective Vol. 19, No. 1, Special Issue on Contemporary China (Spring-Summer 1995), pp. 99-115

It goes over the social position of the traditional martial arts, before, during and after the Cultural Revolution in Guangdong. Yeah, lots of really bad stuff happens, but the process is actually a little different than we tend to think in the West, and more in line with what I discussed in this post.

July 3, 2018 at 4:26 pm

Apropos working class and peasant participation in martial arts training. I came across this reference to the CCP organize Peasant Movement Training Institute at the Hong Sheng memorial hall in Foshan in 2013. Best, Bob Lee