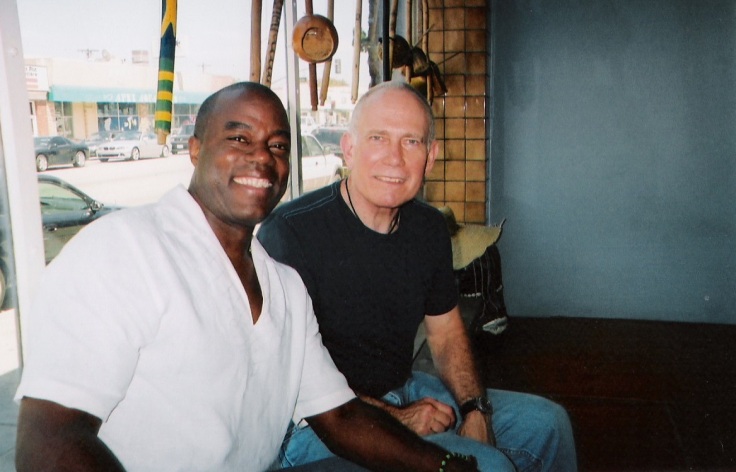

Capoeira Batuque, Los Angeles, CA, 2008. Source: Personal Collection of Prof. Thomas Green.

Introduction

Professor Thomas A. Green (Anthropology, Texas A&M University) has been a critical figure in the promotion of the academic study of the martial arts. Many readers will already be familiar with his edited works (along with Joseph Svinth) including Martial Arts in the Modern World (Praeger, 2003) and Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation (ABC-Clio, 2010). His research and writing covers a number of important topics including the role and function of folklore in the martial arts, African American vernacular martial arts traditions and the emergence and survival of Meihuaquan (Plum Blossom Boxing) in northern China.

Given his many contributions to the scholarly literature, we are very happy that Prof. Green has agreed to drop by Kung Fu Tea and tell us a little about his introduction to the field, his thoughts on the current state of martial arts studies and his on-going research projects. Students of Chinese martial studies will find the discussion of his forthcoming research on the vernacular martial arts of northern China to be especially interesting.

Kung Fu Tea (KFT): First off, can you tell us a little about yourself? What are your main research interests, and how did you become involved with the academic study of the martial arts?

Prof. Thomas A. Green (TG): I became involved with martial arts a long time before I became involved in the academic study of martial arts. I suspect I’m not unique in that regard. Most of the martial arts scholars with whom I’m acquainted were martial artists before they began to try their hands at investigating martial arts from their particular academic perspectives. In my case, I tried some amateur wrestling in high school and found a local brown belt in judo who my friends and I managed to nag into starting a judo class at the local YMCA. I continued training in martial arts off and on, whenever and wherever I could find them, to the present.

While pursuing a degree in English Lit at the University of Texas (Austin) I was fortunate enough to stumble across the discipline of Folklore. There, under the tutelage of Roger Abrahams, Richard Bauman, and Américo Paredes, I was exposed to interdisciplinary approaches to the ways in which traditional art forms (especially dance, drama, games, festival, and narratives) can serve as vehicles for creating, articulating, and managing cultural hopes, anxieties, and identities.

As a result, I developed a focus that still informs my research. I’m interested in vernacular martial culture (inter-relationships between fighting systems and other areas of society as these arise at the local level), symbolic studies, and the aesthetic features of martial behavior.

With these interests and my background reading in the popular histories of martial arts, I inevitably began to see traditional motifs in the oral histories of the martial arts I studied. Twenty-five years ago, I gave my first paper applying my research interests to martial arts at the American Folklore Society meetings. At that point, the topic was considered exotic, and I don’t believe there was another martial arts paper at the AFS until I gave my second in 1997.

In the same year, Folklore: An Encyclopedia of Beliefs, Customs, Tales, Music, and Art was published, and my editor approached me about editing another encyclopedia, one on ritual. I told him I wasn’t interested in doing that, but I would put together one on martial arts. The publisher rather reluctantly agreed. There was some hesitation because the publisher didn’t seem to be an academic market for such a publication. I still can’t believe I was so arrogant as to take on that project, but with the help of some remarkable and dedicated contributors, Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia went to press in 2001. One of these contributors, Joseph Svinth, signed on as co-editor when, in 2010, I took on a second run at the topic with Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation.

KFT (2): You have been writing on the martial arts for some time. What are the major trends that you see in the field? In your opinion, why are more scholars looking into these subjects now?

TG (2): I’m happy to say that I see a growing trend in characterizing martial arts as embedded in the greater culture rather than describing them as discrete and separable phenomena. I’m reluctant to speak for all scholars in all disciplines, but I think beyond personal interests the following have had an impact on my research.

First, I would cite the growing global influence of Asia socially and economically–Japan, then Korea and now China. And, while I am a strong advocate of extending the concept of martial arts beyond Asia, I’m sure that has fueled contemporary scholarship. The acknowledgment of martial arts as a form of intangible cultural heritage as defined by UNESCO has given recognition, prestige and political and economic support to martial arts research.

Finally, in the social sciences, the notion of carnal sociology and embodied ethnography popularized by Loïc Wacquant in Body and Soul goes a long way toward legitimizing the sort of work attempted by those of us who are both academics and martial artists. There are many other influences, of course, but these are the ones that stand out to me.

KFT (3): What special tools or insights do anthropologists bring to the table when studying the martial arts?

TG (3): Actually, I self-identify as a folklorist, as I mentioned earlier. Although my PhD was earned through an anthropology program, my first two degrees were in Literature. I’m currently housed in an anthropology department (after stints in English as well as other anthropology departments and having had joint appointments along the way). All of this gives me a tool kit that may not be true of all anthropologists.

For example, many contemporary anthropologists espouse being scientific and quantitative. In contrast, my work inclines to the humanistic and qualitative similar to the work of Clifford Geertz and Victor Turner in kind though not in quality. That said, like any good anthropologist, I pay close attention to the cultural context of those art forms I study. The anthropologist and especially the folklorist differs from the historian, I think, by assuming that we can learn as much from a culturally grounded lie or an invented tradition as we can from verifiable facts. In general we are as interested in the fictive “histories” that comprise the folk histories of a group as we are in the “great traditions” of the elites—maybe even more so.

I think one of the great strengths of the anthropological method (and the methods of the anthropologically inclined folklorist) is the commitment to participant observation, participating in those events that we attempt to study and translate. The popularity of martial arts and increasing availability of instruction puts many of us in the position to take on the role of analyst after we have already participated corporeally.

KFT (4): A lot of the discussion of martial studies that I have encountered recently has stressed the idea that this is an “interdisciplinary” research area. In fact, interdisciplinary approaches seem to be quite popular throughout the academy right now. Will this ultimately be helpful to the growth of “martial arts studies” as a unique research area?

TG (4): As I mentioned earlier, folklore has historically been an interdisciplinary endeavor, so I’m comfortable with that approach. The fact that we practice the interdisciplinary as a matter of course and very often throw in the international perspectives and multi-sited ethnographies that are embraced just as fiercely should allow us to “hold our heads a bit higher” at faculty meetings. So, yes, general academic acceptance coupled with the efficacy of our interdisciplinary approach can only have a positive effect on martial studies.

As for martial studies specifically, we are attempting to understand an embodied art form. How can we hope to do so without confronting the vessels of that art as mind, body, and socio-cultural beings? A good example of this current research is Fighting Scholars: Habitus and Ethnographies of Martial Arts and Combat Sports edited by Raul Sanchez and Dale Spencer (2013). Forgive that shameless plug, but I believe the articles in this collection are good examples of what we’ve been discussing. In my experience, our academic peers all too often have dismissed martial studies as marginal.

KFT (5): I greatly enjoyed your essay “Sense in Nonsense: The role of folk history in the martial arts.” Why is the study of martial arts folklore important? What sorts of avenues of inquiry can it open for us that a purely historical approach might miss?

TG (5): One of the first definitions I force on my folklore students is that a “folk group” is any group of people sharing at least one common trait and self-consciously organizing an identity around that shared factor. Folklore arises from and articulates that self-consciously organized identity.

Particularly in contemporary contexts, but historically as well, the martial arts have been important vehicles for establishing social identity. Common histories and role models, shared rituals and ceremonies are the tools through which groups establish identity.

In terms of historiography vs. folk history, historiography strives to give an accurate account of events. Folk history, on the other hand, presents a group’s perception of itself and others, especially competitors, oppressors, and rivals.

KFT (6): Can you tell us a little bit about your research on Plum Blossom Boxing in Shandong, Hebei and Henan?

TG (6): At the 2010 meetings of the Pan-Asian Society of Physical Education, in Nanchang, China, I met Professor Zhang Guodong (Southwest University, Chongquing, China). In addition to his academic background in physical education and sports history, Prof. Zhang’s paternal and maternal grandfathers, as well as his uncles are martial artists. While growing up in his village in Shandong, he began learning Plum Blossom Boxing, Shaolin Boxing and Hong Boxing. In 2007 Zhang began field research on Plum Blossom Boxing in his hometown of Heze and later extended his investigation into neighboring provinces. Together we are investigating the reasons for the contemporary survival of Meihuaquan (Mandarin, “Plum Blossom Fist [Boxing]”) as a village level art practiced in Shandong, Hebei, and Henan Provinces, China.

The existence of Mei Boxing has been documented from the mid-seventeenth century. Cultural, economic, and environmental factors in the region gave rise to heterodox political and religious beliefs that frequently served as a catalyst for martial sects, most notably the “Boxers” of the turn of the twentieth century, who came into conflict with the imperial government.

The fall of the Qing Dynasty in the early twentieth century brought concerted efforts by both Nationalist and Communist governments to extinguish village boxing in favor of more standardized and politicized sporting activities. Despite ideological differences between the two parties, many of their objections to vernacular martial arts coincided. Traditional martial arts were said to embody antiquated modes of thought and behavior.

Therefore, during the Nationalist Period (1927-1949), there was an effort to modernize and standardize the traditional Chinese martial arts and bring them into line with the nationalist ideology and to incorporate standardized forms into the public school curriculum. The People’s Republic of China was established in 1949, and by 1959 martial arts were standardized into a narrow spectrum of competition forms resulting in the suppression of traditional styles. Accused of fostering practices characteristic of feudalism, traditional martial arts came under even heavier attack during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). By the late 1990s, however, official attitudes had been relaxed to the point that the Chinese government now promotes both old-style martial arts and standardized wushu, with the latter being featured in conjunction with the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

In the twenty-first century, traditional martial arts are no longer necessary for community defense. In addition, these arts were subjected to almost a century of suppression, and contemporary teachers at the village level receive little if any financial compensation, certainly not enough to repay them for the time and efforts expended in teaching novices. Why then do the arts and their bearers survive? Prof. Zhang and I are interested in answering that question, and we are particularly interested in exploring the symbolic and expressive vehicles (e.g., festival, legend, folk drama, and ritual) that perpetuate the group identity and social solidarity necessary for such survival.

KFT (7): Pushing a little deeper on the same subject, how have the martial arts helped these rural Chinese communities resist some of the more destructive pressures of modernization and globalization?

TG (7): Membership in the village level martial “families” that are an element of the master-apprentice system invariably entails maintaining connections to the head of one’s martial family despite relocations to urban areas in pursuit of employment. Beyond the practical need to maintain contact with one’s master for instruction, each system contains ties to local rites dedicated to the deified patriarchs of the local systems. This ancestor veneration and the recurrent festivals that are vehicles for the worship of local deities promote a continuing renewal of local and ancestral ties.

Our research strongly suggests that Meihuaquan serves as a focus for social life. It helps local people satisfy their need for social participation, expand their social networks, and fulfill their religious needs. The inclusion of Mei Boxing, and other vernacular martial arts, on the list of Intangible Cultural Heritage items developed by the State Council of China in 2006, and the pride this has engendered, has definitely encouraged the perpetuation of both the arts and the survival of the communities in which they reside.

KFT (8): Can you tell us a little bit about your research on the martial arts in the African American community? Do you see the same mechanism and pressures at work in both China and the United States, or are these two separate stories?

TG (8): African-American folklore was an early interest in grad school, but my research had taken off in other directions until the late 1990s when I began work on Martial Arts of the World (2001). I was determined that the encyclopedia would not be limited to Asia. I had difficulty finding authors for African America and Africa, so I took on the job with assistance from Gene Tausk. I should add that since that time I have found a number of extremely knowledgeable experts. Anyway, I was not particularly pleased with my initial effort and was challenged to educate myself on African and African-descended martial culture.

The similarities that jump out at me are related to the fact that, in contemporary contexts at least, martial arts are symbolic vehicles. This is as true of the practices of the African-American cultural nationalists as it was of the “Boxers” in the final decades of the Qing Dynasty. In both contexts we see martial culture used to empower the relatively powerless. In addition, in both contexts martial arts are heritage arts. That is, they provide a link to positive cultural identities in a genuine and/or imagined past.

KFT (9): I notice that in your writings you often refer to the “vernacular martial arts.” What is the significance of that phrase or concept?

TG (9): I borrowed the label “vernacular” from linguistics and art criticism. The term “vernacular” is used in linguistics to denote a local language, dialect, or non-standard version of a language and in art criticism for the creations of people who are detached from the movements and trends of fine art.

I actually was led to develop the concept of vernacular M.A. through my encounters with African-descended martial arts. The terms “traditional” and “folk” simply didn’t address what I saw going on in vernacular arts such as knockin’ and kickin’, the 52s, kalinda, or any number of other non-institutionalized arts that I became aware of during my research. “Folk” in popular usage tends to imply cultural forms that are inferior or “second class.” On the other hand, “traditional” can be applied as easily to elite and bureaucratized martial arts as it can to the forms that arise in and are localized to the street or the village.

In various historical periods, centralized, bureaucratic structures were created for the governance of many martial arts. Ranks and consistent testing policies became standard. These policies became the traditions of such arts. Throughout the 20th century and into the 21st century these traditions have become formalized globally as many martial arts have sought to enter the international arena as combat sports.

The vernacular martial arts (VMAs) contrast to systems that maintain lineages, curricula, and that issue certificates and other designations of rank. VMAs meet the needs of the local groups in which they are practiced and preserved rather than being responsive to external standards or bureaucracies. Proficiency in these vernacular arts is acquired by informal methods of instruction VMAs share the following characteristics. Their curricula are relatively non-structured. Knowledge usually is passed along by oral transmission and in a casual fashion, rather than as a progression from basic to more complex skills. For example, techniques may be passed along by an experienced fighter to a favored novice. Compared to formalized martial arts, more often knowledge comes through observation rather than regimented instruction. Techniques are polished through combat in a culturally appropriate context. Vernacular dance and related musical forms reinforce patterns characteristic to the martial form. In some contexts, vernacular arts compete with state sanctioned culture.

These factors cause the survival of any given vernacular art to be dependent to a far greater extent on oral transmission, ethnic tradition, and individual initiative than is the case with more centralized and formalized arts. In cases in which martial practices have remained tied to a local cultural tradition, efforts at globalization and standardization are especially problematic.

Because of the factors just noted, these arts are rarely documented in the historical record. There are a few notable exceptions, Brazilian Capoeira in the 19th century is the most obvious example.

KFT (10): What does your current research agenda look like? Or put another way, what should readers be watching for in the future?

TG (10): I remain interested in both African-American and Chinese VMAs, but since Prof. Zhang is a visiting scholar at my university until next spring, I’m focused most intensely on writing up our research on Meihuaquan. I hope we’re about a year away from a draft version, but since most of the relevant material must be translated from Chinese to English, that twelve month completion date may be optimistic. In a nutshell, we want to cover the origins of vernacular Mei Boxing during the Ming Dynasty, its contemporary functions, and the impact of modernity and official recognition. In many ways, this also should tell the story of transformations in Northern Chinese vernacular culture in the late 20th-early 21st centuries.

oOo

If you enjoyed this post you might also want to read: Lion Dancing, Youth Violence and the Need for Theory in Chinese Martial Studies

oOo

5 Pingback