The Book Club is a semi-regular feature here at Kung Fu Tea in which we read and discuss a major work in the field of Chinese martial studies. The basic idea is to replicate the sort of discussion that you might have in an upper level undergraduate class. We want to look at the author’s argument, see its strengths and weaknesses and apply them to some important questions in the field. Feel free to read along with the discussion. No prior background or language skills are necessary. I hope that this series will provide a good way to start thinking and talking about some of the important books that are already out there. For previous editions of the Book Club click here.

Introduction

Stephen Selby is a rare talent. He is a clear and interesting writer, a dogged researcher and a true expert on ancient Chinese archery. We are currently seeing a revival of interest in the subject, and his work has undoubtedly helped to promote and advance that cause. Selby’s grasp of the Chinese language, and his ability to overcome linguist challenges in order to translate and present ancient texts to modern readers, is also exceptional. He can take dry, somewhat technical, primary source documents and make them come alive.

For all of these reasons I have been looking forward to discussing his 2000 volume, Chinese Archery published by Hong Kong University Press. This work is one of only a small number of books in the field of Chinese martial studies to be released by a major university press. And its subject matter could not be more central to those students who are interested in reconstructing a historical understanding of China’s diverse and ancient martial culture.

It is safe to say that archery was the single most important martial subject to be practiced (and written about) in China for the last four thousand years. The military service examination system that was so critical to the careers of martial artists in both the Qing and Ming dynasties placed a huge amount of emphasis on a candidate’s skill in archery. At various points in time the Chinese battlefield has been dominated by the chariot and bow, the infantry crossbowman and the mounted archer. Confucius discusses archery in his writings and may even have taught the subject. The ritual and subtle magic of the bow has informed Chinese literature, poetry and art for thousands of years.

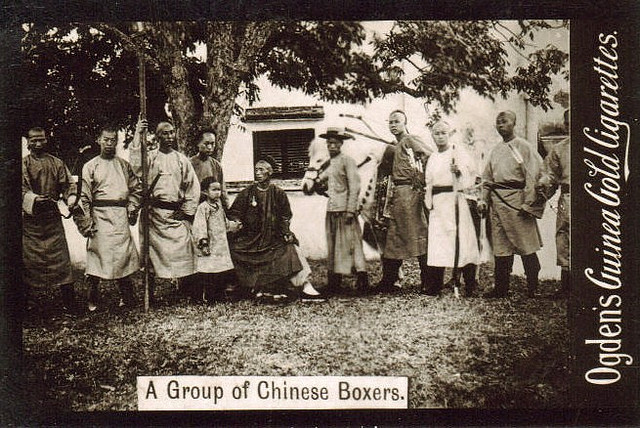

For all of these reasons it is really somewhat odd that we don’t hear more discussion of traditional archery in martial studies circles. The art was practiced by a large number of people in various schools until just after the turn of the 20th century. It also attained a sense of respectability and social stability that virtually no other martial subject could boast.

As a result of its large following and role in the state exam system, it generated a substantial body of written works. These include numerous technical manuals, works of social observation, fictional stories and even poetry. This is critical as contemporaneous texts are the key element which makes Chinese martial studies possible. There are a variety of different sorts of evidence that we see being used in the field (archeological, geographic, cultural, economic data ect…), but there can be no doubt that we collectively rely quite heavily on the contributions of historically significant texts. Having accesses to these sorts of documents, and carefully considering what they imply for our understanding of the nature and evolution of the martial arts, is what makes the current literature in martial studies different from its various predecessors.

In this sense students of traditional Chinese archery are truly blessed. We have very few works which explore hand combat or pole fighting prior to the Ming dynasty. In fact, most of our sources on this material actually date to the Qing or Republic era. There are just enough references in the ancient literature to let us know that boxing flourished in the Song dynasty, or that fencing underwent critical changes in the Han period. Yet this is only enough to whet our appetites. It implies that some form of martial arts probably existed in the ancient past, but it’s not really enough to say much about what was probably going on.

Undoubtedly this stems from the socially marginal nature of most martial training in traditional Chinese society. It wasn’t the sort of subject that most historians were willing to spill much ink on (though gratefully a few did). But archery was another matter. For much of China’s ancient past it was the pursuit of gentlemen and for more than a thousand years after that it remained a critical battlefield technology. As a result it was written about in the military, political and historical literatures.

While the problem facing students of hand combat is the lack of sources, the more pressing issue for those interested in archery is the comparative embarrassment of riches. Of all of the many texts out there, where should one start? What periods of time are the most critical? How should one interpret the fragmented references to archery found on the oracle bones, or understand the social significance of the Confucian archery ritual at various points in Chinese history?

Perhaps Stephen Selby’s greatest contribution is his ability to help the reader grasp the outlines of this forest for all of its trees. It is interesting to note that the author himself has not had a conventional academic career. Selby earned an MA in Chinese from Edinburgh University. After that he lived and worked in Hong Kong for a number of decades. Most of his career seems to have focused on the topic of intellectual property rights management. Currently he is listed as an Adjunct Professor at Hong Kong Polytechnic University where he teaches on this subject.

Apparently Selby’s interest in archery came along a little later. In a radio interview he states that it began as a personal hobby after he was introduced to the subject on a family vacation, and it later took on a radical new direction after he managed to dig up a copy of a Qing era archery manual.

The way in which his personal interest in the subject evolved really makes a great deal of sense after reading his book. It must have been immensely difficult to pick up the highly technical vocabulary needed to deal with some of these texts. Even within martial studies this is a specialized area and it is hard to imagine that any graduate program could linguistically prepare students to do this sort of work. It would have required a lot of hours of personal study.

Likewise academic careers tend not to reward these sorts of narrowly focused projects. Rather than examining archery as a means to understanding critical moments of change in Chinese social history, Selby’s focus remains resolutely on the bow and its technical practice throughout. This does not mean that his work has nothing to contribute to these other questions. It certainly does. But it is clear that his emphasis was always on the practice of archery rather than its broader meaning.

One cannot help but wonder if this book was possible precisely because Selby was writing from a position outside of academics. Not having to worry about whether the annual Review, Promotion and Tenure (RPT) committee would think that your research was sufficiently “relevant” would be a big advantage in putting together a volume like this.

All of this brings up the question of professionalism in Chinese martial studies. I think that until recently most of the people who were interested in these topics were by definition amateurs. There just was not much support for this sort of research within the various academic disciplines.

Luckily for us that has been changing over the last few years, and we have seen a growing body of “professional” literature. Nevertheless, Selby’s volume is a valuable reminder of what a dedicated “amateur researcher” can produce. This is an erudite and engaging text that fully deserves the spot that it found with a university press. Not only that, Selby’s book is currently on its third printing. Clearly there is an audience for this material.

Chapters 1-8: The Bow in Ancient China

I think that the best way to discuss this book is to split it down the middle. Today we will consider the material from roughly the Shang to the Tang dynasties. In the next post we will take a closer look at the second half of the volume. We will also be attempting to look at the Ming and Qing dynasties in a little greater detail.

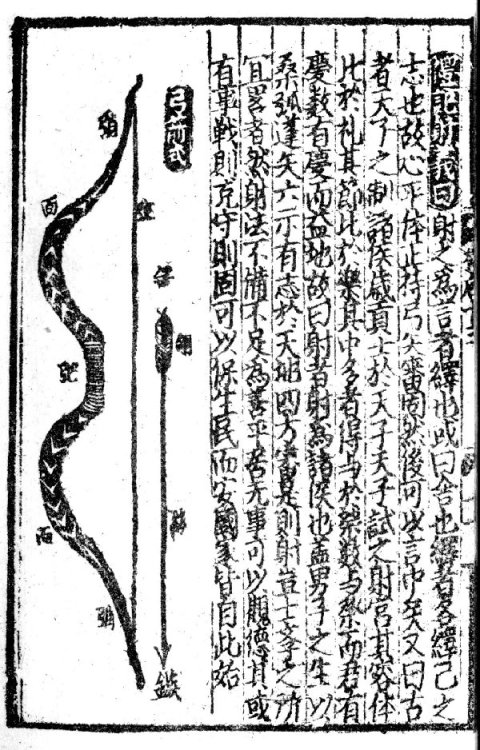

Selby’s book is structured around the presentation and discussion of a number of primary texts. Starting with the earliest oracle bones and proceeding all the way up to the latest discussions of the Qing military exams, the author always followed the same basic format. First a Chinese language text would be presented. This would be followed by a translation. The translation would be followed by a discussion of its meaning and relevance. Often specific technical issues (such as the translation of unknown characters) would be brought up here. Occasionally additional literary or cultural information would be introduced at this point. At the conclusion of this discussion the author would then proceed on to the next Chinese language text.

Individual texts are grouped together based first on their era and secondly on their subject. The books chapters are loosely structured around these thematic grouping and are tied together with brief introductory and concluding remarks which explain to readers where they are about to go and why it is significant.

And it always is significant, sometimes surprisingly so. Obviously students of traditional Chinese archery will already be familiar with this book and Selby’s other work at www.atarn.org because it is simply some of the best information out there. But even if you have little interest in archery per se, the subject still provides a valuable window back onto the deep history of Chinese martial culture. In fact, many of the discussion and trends that arise in archery circles will become directly relevant to later debates in hand combat. These include the importance of “hardness and softness,” the application of the Confucian “Great Learning” to the martial arts, the role of mental training in the fighting styles, and the significance of Qigong and other breathing exercises to attaining martial excellence.

Because the primary texts are arranged in chronological order, Selby’s text ends ups telling a compelling story about not just the evolution of Chinese archery, but also Chinese society. The earliest mentions of archery, found in the oracle bones of the Shang dynasty, link archery directly with the world of ritual and magic. Even warfare and hunting were connected to the larger Shang ritual complex. Of course archery was central to all of these pursuits.

This type of archery (just like warfare and sacrifice) was an elite practice. And it stayed that way for quite a while. Throughout the Zhou dynasty warfare was dominated by a group of minor aristocrats (called the Shi) who moved across the battlefield in horse drawn chariots. The bow and the bronze dagger ax (which could also be wielded from a moving chariot) were the weapons that dominated this battlefield.

Some of the most interesting material in Selby’s book is the exploration of the very early myths, legends and rituals associated with the practice of archery in ancient China. I was genuinely surprised with the depth of the reconstructions that was possible for this time period. The myth of Yi is especially important, as is the extensive discussion of the state sponsored archery rituals of the Zhou dynasty.

Confucius’s writing would immortalize much of this material, insuring that it would always be present throughout the remainder of Chinese history. As such it is interesting to consider both the ideas of continuity and change. Archery is one of those subjects that seems to have gone through an eternal “revival.”

On the one hand it was a critical battlefield technology and as such it was subject to change and evolution. As the heredity nobility of the Zhou was pushed aside in the Warring States period the nature of archery changed. Warfare was no longer the domain on a small group of social elites. Now vast peasant armies took to the field and new types of archery (specifically the crossbow) became necessary. Later the sudden dominance of the Huns on the empire’s northern border would bring about further changes. Crossbows became less helpful than quick shooting mounted archers. We see this same tendency towards innovation in every era of Chinese history.

Yet the canonization of the Confucian classics insured that the ancient archery rituals were never wholly forgotten. There was always a certain pressure to reimagine what was “new” as a continuation of the old. This discussion is a critical aspect of the book as it really helps to justify the idea that there can even be such a thing as “Chinese martial culture” in the first place. That culture may not be defined so much by some absolute continuity of practice, as by the fact that each succeeding generation was forced to struggle with the same literary and philosophical legacy as its forefathers.

Towards the end of the first section of the book Selby includes a translation and a discussion of the story of the Maiden of Yue. This story was first recorded nearly 2000 years ago and has been retold fairly often. It was certainly in circulation in the Ming and Qing dynasties, and it was popular with more literate students of the martial arts.

Usually this story is passed on in a highly abbreviated form. Luckily for us Selby provides a complete translation and detailed discussion of the entire thing. It turns out that the same account was also well known to archery students in the Ming dynasty. The complete story did not focus exclusively on the Maiden of Yue, an acknowledged expert in sword and pole fighting who is invited to be a military instructor. Rather it contrasts her, and her method of fencing, with another martial hero whose expertise lay in the field of archery.

I think that this account is significant enough that I have included an excerpt of both halves of the story below. In his extensive commentary on the piece Selby notes that the two halves of this story create a certain dynamic tension. Obviously the genders of the two heroes contrast with each other, and some elements of what they teach seems to present a Yin/Yang duality. This is probably the reason why Ming era archery manuals often included the story of the Maiden of Yue even though she personally has nothing to do with archery. Rather she is one half of a complete set.

My interest in these stories is two-fold. To begin with they reference an important era in Chinese military history when the nature of warfare was changing. The traditional nobility had disappeared, warfare was now a matter of massed peasant armies, and kings were forced to find new types of instruction to train their forces. Interestingly this story shows a king turning not the teachers of the ancient schools or “ways” (dao), but rather to a new class of civilian military experts who specialize in training other civilians.

What they do is clearly distinct from the older, noble, “ways” of the Shi. At the same time it is also distinct from the modern martial arts. These individuals are clearly military trainers teaching battlefield skills. Still, there is a lot here that seems familiar, more than one might expect given the early date of the original text. We really don’t have any solid discussion of the civilian martial arts as a distinct fighting system prior to the build-up of the new urban centers of the Song dynasty. In truth the historical record is just too spotty to expect much of anything as one goes back further. Still, these stories are an interesting suggestion of what might have been.

Secondly, when reading these accounts it is interesting to contrast the story of Maiden of Yue, and the vision of the martial arts that she describes, with the highly scientific and rational marksman Chen Yin. This debate between the more “mystical” (or at least sensuous) approach to the martial arts and a straight forward rational reading of the practices still goes on today. It was accentuated by the early twentieth century reform movements (such as Jingwu and the Central Guoshu Institute) and many current writers still get a lot of mileage out of it. What the following account suggests is that this difference in approach may be pretty ancient. In fact, it may well predate the structures that we currently think of as the “martial arts” all together.

Zhao Ye (circa AD 40-80): Romance of Wu and Yue. Vol. 9

The King of Yue asked Fan Li, ‘I have a scheme to get even again. For a naval battle, you rely on ships; for a land battle, you rely on chariots: but the power of our ships and chariots is blunted by the quality of our short and long weapons. You are my strategist; isn’t there some scheme to get us out of this fix?’

Fan Li replied, ‘As I recall, the ancient sage kings never failed to exercise in warfare and the use of weapons; and only then did they form up their battalions, line up their divisions and march off to war. The outcome hung on their martial arts instructors. I hear there is a young woman of Yue who came from the Southern Forests; the people of Yue speak highly of her. I think your Majesty should send her an invitation and you can see for yourself how good she is.’

So the King of Yue sent an emissary with a polite invitation to ask whether the King could get her advice on skill in use of swords and halberds.

The Young Woman of Yue travelled north for her audience with the king. On the way, she men an old fellow who said his name was ‘Old Mr. Yuan.’

He said to the young woman, ‘I hear you fight well with a staff. I’d like to see a demonstration.’

She replied, ‘I wouldn’t presume to keep anything from you: you are welcome to test my skill, Sir.’

So Old Man Yuan drew out a length of Linyu bamboo. But the bamboo was rotten at one end. The end fell to the ground and the young woman immediately snatched it up. The old man wielded the top end of the staff and thrust towards the young woman, but the girl parried straight back, thrust three times and finally raised her end of the bamboo and drove home her attack against Old Man Yuan. Old Man Yuan hopped off up a tree, turning into a white ape. Then each went their own way, and she went to meet the King.

The King asked her, ‘of all the methods of fighting with the staff which is the best?’

She answered, ‘I was born in the depths of the forest and I grew up in the wilds where no other people ever ventured. So there was no “method” for me and I followed no course of instruction, for I never ventured into the feudal fiefs. Secretly I yearned for a true method of fighting and I practiced endlessly. I never learned it from anyone: I just realized one day that I could do it.’

‘And what method do you practice now?’ asked the King.

‘The method involves great mystery and depth. The method involves “front doors” and “back doors” as well as hard and soft aspects. Opening the “front door” and closing the “back door” closes off the soft aspect and brings the hard aspect to the fore.

‘Whenever you have hand-to-hand combat, you need to have nerves of steel on the inside, but be totally calm in the outside. I must look like a demure young lady and fight like a startled tiger. My profile changes with the action of my body, and both follow my subconscious. Overshadow your adversary like the sun; but scuttle like a flushed hare. Become a whirl of silhouettes and shadows; shimmer like a mirage. Inhale, exhausting, moving in, moving back out, keeping yourself out of reach, using your strategy to block the adversary, vertical, horizontal, resisting, following, straight, devious, and all without sound. With a method like this one man can match a hundred; a hundred men can match ten thousand. If Your Majesty wants to try me out, you can have a demonstration right away.’

The King of Yue was overjoyed and immediately gave her the title ‘Daughter of Yue.’ Then he ordered the divisional commanders and crack troops to practice the new method so that they could pass on their skills to the troops. From then on, the method was known as ‘The Daughter of Yue’s Swordsmanship.’

Then Fan Li went back to the king and recommended the marksman, Chen Yin. Yin was from Chu. The King invited Yin over and asked, ‘I hear you are a fine marksman. Tell me, what is the origin of archery?’

Yin replied, ‘I’m just a country bumpkin from Chu. I’ve tried to make some progress in archery, but I don’t know the art thoroughly yet.’

The King said, ‘In that case, I would just like you to tell me what you know from the beginning.’

Yin said, ‘As far as I know, the crossbow originated from the bow and the bow originated from the stone-bow. The stone-bow had its origins with “The Pious Son.”

‘Tell me about how the “Pious Son” invented the stone-bow,’ said the King of Yue.

Yin answered, ‘The people of ancient times were rough fellows: when they were hungry, they ate wild birds and animals; when thirsty they drank the dew. When they died, they were wound in cogongrass and [their bodies] left in the open air. “The Pious Son” could not bear to see his father and mother ultimately being eaten by the birds and beasts, so he made the stone bow to stand guard with over their bodied and put an end to the predations of the birds and beasts. That’s why there’s an ancient chant:

Cut the bamboo; splice the wood:

Pebbles fly to catch our food!

From then on, the dead were spared the humiliation of being defiled by [carrion] birds and foxes.

‘Next the God of Agriculture and the Yellow Emperor strung wood to make the bow, whittled wood to make arrows; and the power of the bow and arrow allowed them to dominate in every direction. After the Yellow Emperor came “The Bowman of Chu.” “The Bowman” was born in the Jing Hills in the Land of Chu. His father and mother disappeared at the time he was born, and as a child, he learned to shoot so well with bows and arrows that nothing could ever escape his shafts. He passed on his skills to Yi. Yi passed his skills to Pangmeng, who in turn passed them on to the Clansmen Chu.

Clansman Qin considered the bow and arrow insufficient to achieve total domination. In his time the fiefdoms were fighting one another, everywhere clashes of arms was heard. So Clansman Qin turned the bow on its side and added a stock, invented the trigger mechanism and its housing and added power to the bow with the result that the fiefdoms could be brought under control. Clansman Qin passed on [his skill] to great wei, and Great Wei passed them on to the Three Fiefs of Chu, known as Dan, E and Zhang; their personal names Lord Mi, Lord Yi and Lord Wei. From the Three Fiefs of Chu skill passed to King Ling of Chu, and since the Kingdom of Chu entered onto the world stage, all the generations have armed themselves with a peachwood bod and jujube arrows to fend off neighbors. After King Ling of Chu the art of archery became fragmented and even the ablest men in all the families could not fathom it. Before I was taught the art in Chu it had already passed through five generations. Although I am no adept in the art, Your Majesty is welcome to test me if you will.’

The King asked, ‘What makes the composition of a crossbow so effective?’

Yin answered, ‘The firing mechanism is like the walls of a city: it protects all the “ministers: The trigger-lever is the overlord: all commands originate from it. The release is the enforcer: it controls the officers and men. The latch is like a lieutenant: it holds the inner formation in check. The firing mechanism assembly is like the cavalry commander: it commands an advance or a halt. The axle-bolts are passive servants: they comply with whatever is ordered. The stock is like a roadway, it provides a path for whatever is sent. The prod is like the general, it is responsible for the most onerous duties. The string is like the commander, it drives the warriors. The quarrel is like the flying knight: at the command and guidance [of the master]. The arrowhead is the penetrator of the enemy: it charges forward and never stops. The fletching is like an assistant commander: it corrects the line of attack. The lobes of the nock receive the order: Once acknowledged, they are never disobeyed. The riser of the prod is like the lieutenant of the center division: it keeps left and right [phalanxes] in order. The point of the quarrel is the killer of hundreds: no one can dodge it. Birds cannot get away, beasts have no time to flee; for whatever the crossbow is aimed at dies without fail. That is the method as I learned it.’

The King of Yue said, ‘I wish to hear about the proper method of archery.’

Chen Yin replied, ‘I have heard of the methods of archery; there are many and they are profound. When people in ancient times shot with the crossbow, they could name the exact spot they would hit even before pulling the trigger. I am no match for the archers of old, so please accept the basic outline. The basic form in all shooting is: the body is erect as if it were held in a wooden frame; the head relaxed like a pebble rolling in the stream; the left foot aligned with the target; the right foot at right-angles to the target; the left hand as if glued to the grip; right arm as if cradling a baby; you raise the crossbow towards the enemy; draw your concentration together as you inhale and then fire in coordination with your breathing so that the whole series of actions is in harmony. Your inner mind is settled and all conscious thought must be driven out. There must be absolute separation of those parts that move from those parts that don’t: the right hand pulls the trigger and the left never reacts, as if one body were controlled by totally different impulses set at opposing extremes. This is the orthodox method of shooting with a crossbow.

[The King said] ‘I want to know about the relationship between the use of aim, physical considerations and calibration of elevation in determining the flight of the arrow.’

Chen Yin replied, ‘The rule in all archery is: let your eye follow the calibrated line of fire from you to the target, then line up the three elements 9calibration, arrowhead and target). The power of the crossbow is measured in heavy or light poundage; arrows differ in their weights. The ratio of arrow weight to bow poundage is one ounce to one stone (120 catties): this gives you the correct proportion. Different distances and elevations can be compensated by minute differences in this weight. This is the whole method: I have held nothing back.’

The King said, ‘That’s fine. I’d like you to use your expertise to teach our citizens.’

Chen Yin said, ‘All orthodox methods follow the rules of nature, but their application lies in the individual. Whether the individual attains what he studies or not has no mystery to it.

The King then arranged for Chen Yin to instruct his officers outside the northern suburb. After three months, the troops and officers all became proficient in the use of the crossbow. When Chen Yin died, the King regretted his loss bitterly and buried him in the Western Hills and they called his grave ‘Chen Yin Hill.’” (Selby pp. 155-161)

oOo

There are a number of points in the previous account that bear close consideration. In fact, there is more material in these stories that we could cover in a single post. The Maiden of Yue explains her art (which focuses on pole and sword fighting) in terms that would not be all that foreign to many Chinese martial artists today. We are still debating the relative merits of “hard” vs. “soft” and the various “gates of attack and defense.” Her art is proven by an encounter with a mystical being and it displays certain evasive characteristics. Clearly mental training is a large part of what the Maiden of Yue advocates.

What might not be so clear to the casual reader is that many of the terms and ideas that she references are also part of the discussion of military archery. For instance her discussion of hardness and softness is actually pretty reminiscent of a lot of other discussion of those same terms that can be found in Selby’s book. Given that this story was included in a number of archery manuals throughout Chinese history perhaps we should not find this all that surprising. Still, it raises some important questions. To what extent did other martial arts schools feed off of and borrow both terms and ideas that had been initially applied to archery?

It is interesting to see that both of our subjects deny that they are teaching a “way” (or “Dao”) when directly questioned on it. Of course it has once again become fashionable to attach that term to a variety of martial arts. But in this context it had a very specific meaning. A “way” was part of a complete philosophy of education. It was associated with noble pursuits and the now defunct hereditary nobility. Both instructors went to some lengths to distance themselves from these systems. That is an interesting social observation in its own right, but it may suggest something more. Perhaps when thinking about the very early origins of the martial arts we should be considering these sorts of civilian schools rather than the ancient “ways” of the nobility.

Selby spend most of his effort analyzing the discussion of the crossbow given by the marksman Chen Yin. He points out that multiple parts of his speech could have been borrowed from ancient, no longer extent, archery manuals. That certainly sounds possible as I read back over the passages. But it also occurs to me that the same might be said of the Maiden of Yue. Consider her final summation of her style:

“Inhale, exhausting, moving in, moving back out, keeping yourself out of reach, using your strategy to block the adversary, vertical, horizontal, resisting, following, straight, devious, and all without sound.”

This certainly sound like the sort of list of mental prompts, or concepts, that would often be seen in much later boxing manuals. And while Chen Yin may at first seem to be almost the opposite of what one often associates with the “traditional arts,” his account has some interesting features to consider as well.

Unlike the Maiden of Yue who is self-taught (though her skills were verified by a divine being), Chen Yin, in his discussion of the history of archery, presents to the King what is essentially his own genealogical lineage of instruction. While he may not claim to practice a “way” he is certainly not without teachers or a school. Like other lineages this one traces its origins back to mythological figures (the Pious Son) and is eventually brought down to the present through a series of generation. Also like modern lineages it is impossible for current practitioners to live up to the martial genius of their ancestors, but there is no doubt that they practice the same art. In fact, this is probably one of the earliest accounts that we have a proto-martial arts lineage. And notice that it is being presented in the context of a job interview. Lineage functions as a social guarantee of the purity and stability of an experts practice.

Conclusion

This discussion has already run long, but it has only scratched the surface of what readers will find in the Selby’s book. Overall this is an excellent resource and a great contribution to the field of Chinese martial studies. I do have a few complaints. I wish that the author had spent more time discussing the archers themselves (for instance, an in-depth discussion of the “Shi” would have been an invaluable). Likewise I would have liked more information on the archery societies of the Song dynasty.

It might a little unfair to criticize an author for not including additional topics in a book that is already 400 pages long. Every project has its limits and there are other sources that that treat this material. Still, I would have liked to have seen what Selby could have made of it.

Likewise I would have liked to have seen more information from the archeological record. The book focuses almost exclusively on literary evidence, but I think that this is one area where archeological artifacts might be very helpful. I really enjoyed the places where the author turned to this information and would have liked to have seen more of it.

Nevertheless, my most serious complaints are with the book’s publisher. I really hope that this volume is reprinted or gets a second edition. In either case it needs an aesthetic update. The computer rendered title pages and covers are now looking seriously dated. While that’s a minor quibble the poor quality of the digital reproductions of many of the figures and illustrations used throughout the book is a more serious issue. Lastly, while the book was printed on high quality paper the spine of my volume started to delaminate before I was even done with my first reading. These are issues that have nothing to do with Selby or his text, but they do detract from the overall experience of reading the book and they should be corrected in the future.

Still, this is one of the more valuable and informative books that I have read on the historical aspect of Chinese martial studies. If I ever get a chance to teach a class on the Chinese martial arts I predict that at least a few sections of Selby’s book are going to end up on my syllabus. In the following installment of this discussion we will review the middle and late dynastic periods, with a more pronounced emphasis on the chapter dealing with the archery of the Ming and Qing dynasties.

12 Pingback